You’ve likely heard the well-known proverb, “The eyes are the window to the soul”. This actually is a particularly appropriate phrase when diagnosing fish health problems. Very often, the first sign of an external disease in fish shows up as a change in their eye’s structure, color, clarity or shape. It is not so much that the fish’s eyes are affected by disease first, just that early changes in the outer body of a fish often show up better on the clear tissue of the fish’s eye. Knowing how these eye changes can be used to diagnose fish diseases is a very helpful technique in an aquarist’s arsenal of fish disease diagnostic tools.

You’ve likely heard the well-known proverb, “The eyes are the window to the soul”. This actually is a particularly appropriate phrase when diagnosing fish health problems. Very often, the first sign of an external disease in fish shows up as a change in their eye’s structure, color, clarity or shape. It is not so much that the fish’s eyes are affected by disease first, just that early changes in the outer body of a fish often show up better on the clear tissue of the fish’s eye. Knowing how these eye changes can be used to diagnose fish diseases is a very helpful technique in an aquarist’s arsenal of fish disease diagnostic tools.

How fish use their eyes

Obviously, fish use their eyes in basically the same manner as any vertebrate. Light enters the eye, is focused by the pupil, and falls on a receptor that makes an image that is then sent to the fish’s brain where it is interpreted. Water has a different specific gravity than does air, so a fish’s focus adapts to that, and they cannot see clearly out of the water. One exception to this rule is the four-eyed fish, (Anableps sp.). This unusual fish has a split eye – the lower part is adapted to focusing underwater, while the top half has a different focal point and allows the fish to see possible predators in the air above the water’s surface where it lives.

Many fish have their eyes on either side of their head (Flatfish, soles and flounders excluded). This works to their advantage in being able to see clearly both to the left and right of their body from almost in front of them to almost directly behind. However, these two separate signals mean that the fish must process two images at the same time, and they lack depth perception because there is little or no overlap in the image they receive. Predatory fish require depth perception in order to capture their prey, so their eyes are either placed more forward on their head, or their pupils are elongate, allowing them to have a greater range of depth so that they can more easily judge the distance of potential prey items. The lack of depth perception in many fish can be used to the aquarist’s advantage; capturing a fish can often be more easily accomplished by using two nets, and coming at the fish from two different directions at once. The fish is unable to adequately process the visual information coming at them from two directions, gets confused, and can be netted much more easily.

Aquatic environments are not always conducive for the use of eyes to receive and interpret visual signals. Fish have problems seeing in murky water, or at night. The flashlight fish overcomes the latter problem by having pockets of luminescent bacteria in special light organs beneath each eye. They can use the light from these bacteria to see their prey at night, and also to confuse potential predators (Hemdal 1986).

Fish lack eyelids (although sharks and some other fish have a nictitating membrane that they can close over their eyes to avoid mechanical damage). Fish also seem to lack a rapidly responding iris to quickly limit the amount of light entering the pupil. For these two reasons, fish are unable to adapt to rapid changes in light levels, and some species may react to such a change by going into systemic shock if the light level changes too quickly. Since this shock reaction cannot easily be predicted by aquarists, it is always best to slowly ramp up the lighting in an aquarium so the fish are not startled by a sudden change in intensity. Additionally, since they do not have eyelids, diurnal fish (those active during the day) should be given a mostly dark aquarium at night so that they can receive a proper amount of “down time” that functions as their sleep mechanism. Although fish can survive under “24/7” lighting for long periods, (personal observation) it is prudent to avoid such

constant lighting in order to reduce overall stress levels in the fish.

Health issues

A variety of health issues can involve the eyes of a fish, from a slight cloudiness to ennucleation – the loss of the entire eye. Knowing if the problem affects one or both eyes is very important. If the problem affects just one of a fish’s eyes, the cause is likely to be a specific injury to that eye alone. If both eyes are equally affected, the problem is not likely to be a simple injury, and there is more of a chance that the problem is systemic – involving the entire fish, or in the case of multiple animals showing the same symptom, the entire aquarium.

Most eye examinations in captive fish must be performed while they are swimming in an aquarium. A small blue LED penlight may help illuminate the eye of the fish assuming it doesn’t swim away too quickly. A more comprehensive exam can be performed if the fish can be sedated and held out of the water for a moment. In these cases, the blue LED penlight can be held at an angle to the eye, causing any ulcers to create shadows, giving them better definition. Veterinarians can also use fluorescein dye to create even greater contrast in the eye lesions (Stoskopf 1993).

Cloudy eyes

If a fish’s eye seems cloudy, the first task is to determine if it may be normal for that species. Some puffers, rabbitfish, scorpionfish and walleye have a normal cloudy sheen to their eyes. This will be seen in both eyes equally, and will always be present under the right viewing conditions. It the cloudiness appears over time, it is not a normal condition for that fish.

The next determination is the cloudiness on the eye’s surface, (on the surface of the cornea) or deeper inside the organ (involving the pupil). A fish with one eye that has a cloudy cornea has likely just injured the eye and time will often heal the problem (assuming no secondary bacterial infection arises). A fish, (or multiple fish) with both eyes having clouding to their corneas usually indicates a systemic problem. This may be poor water quality, a bacterial or protozoan infection or very often, a trematode (fluke) infection.

Disease induced eye problems

Bacterial diseases

If a fish gradually develops only minor bilateral popeye, (usually without cloudiness to the cornea), a bacterial disease may be the cause. Fish tuberculosis, Mycobacterium marinum is a very common, chronic disease that can cause this. This bacteria is ubiquitous – that is, it is commonly found in aquarium water, soil, and even in many frozen fish foods. Some species of fish are more prone to becoming infected than others, and there is no proven treatment for this malady. Additional symptoms of this problem can include emaciation, (loss of body mass despite the fish feeding well) darker than normal coloration, rapid breathing and lethargy. In marine fish, it is generally a “disease of old age”, so only long-term captive fish seem to succumb to it.

If an external bacterial disease is suspected, gentamicin sulfate, an aminoglycoside antibiotic has been shown to help. Because this antibiotic is applied topically, and is water-soluble, it is probably better to use the ophthalmic ointment as opposed to the aqueous solution as the latter will immediately wash off the fish’s eyes when the animal is returned to the water. Some aquarists have reported using this drug in conjunction with dorzolamide hydrochloride (Trusopt) in cases of external bacterial eye infections combined with mild exophthalmia. Truspot is a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor used in humans to reduce ocular hypertension. It is presumed that this drug may have a similar effect on eye swelling in fishes.

Fungal disease

External fungal diseases are extremely rare in marine fishes, but Saprolegnea sp. is a fungus that will often infect freshwater fishes at the site of a previous injury. In most cases, the individual threads or hyphae are visible to the naked eye, or by using a simple hand lens. There is some debate about the need to control Saprolegnea or not. This fungus feeds on dead tissue, which might otherwise become infected with bacteria. Some aquarists advocate leaving it alone to “clean” the wound. If the wound is so severe that the fungus takes over, the fish would have died from the injury anyway. At issue here is that a fungal infection on the fish’s eye may leave scarring that would affect the fish’s ability to see. Anti-fungal treatments may be warranted in these cases, either methylene blue at two parts per million, or sea salt at 4 parts per thousand (if the freshwater fish will tolerate that level).

Gas bubble disease

This syndrome more typically produces gas bubbles on the body of seahorses, (including the male’s brood pouch) but can also involve the skin around the eyes. The cause of this problem is not well known, and only experimental treatments have been proposed. Injections with acetazolamide at around 5mg per kg have shown promise in treating this disease, but that treatment is an off-label use of the drug, and outside the ability of most home aquarists to perform. Many aquarists have attributed this syndrome to supersaturation of the water with gas – making it an environmental condition (covered in the next section). However, it has been repeatedly shown that gas bubble disease can infect seahorses in aquarium systems that are not undergoing supersaturation, so the cause of the problem must be found elsewhere.

Parasites

Cryptocaryon irritans (marine ich or whitespot disease) can cause cloudy eyes, but there are always secondary symptoms such as distinct white spots on the fish’s body. Trematodes, (flukes) will very often cause cloudy eyes as the primary symptom. Neobenedenia sp. in particular is very commonly seen in marine aquariums. Sometimes called “eye flukes”, (although they live unseen on the fish’s body just as well) this parasite will require proper treatment in order to save the fish.

This trematode is best eradicated using Praziquantel administered in a quarantine tank at a rate of 0.20 ppm for seven days, followed by a 50% water change and then administer a second dose followed by a second water change seven to ten days later.

Freshwater dips for five minutes will help to diagnose this malady. After such a dip, look at the bottom of the container for white, 1 to 2 mm oval shapes – these are dead flukes. Because Neobenedenia sp. is an egg-laying species, the flukes will still be present in the aquarium, even if the dip removed most of them from the fish.

Environmentally induced eye problems

Physical trauma

A Lyretail anthias with severe bilateral Exophthalmia – two surgeries did not resolve it, so the fish was humanely euthanized.

Injuries can cause exophthalmia from identifiable sources of trauma (such as resulting from a fish that was recently captured and moved) but it is often from an unknown cause. The eye may or may not have clouding of the cornea, and bubbles may or may not be present. If this problem is suspected, the best treatment is to keep the fish safe from further trauma and see if it will resolve on its own. Aspirating the fluid or gas from behind the eye with a hypodermic needle is usually ineffective, and may actually cause additional trauma through repeated handling the fish. Remember that capture trauma is one of the primary causes of exophthalmia, so capturing the affected fish time and time again to withdraw the gas or fluid is likely to only increase the damage. At the very least, it is imperative to use a sedative or anesthetic when attempting this sort of surgery, both to reduce the fish’s thrashing about, as well as humane consideration of the animal. For unknown reasons, mechanically induced exophthalmia is always restricted to marine fishes.

Some species of fish reported to be susceptible to mechanical exophthalmia:

- Bigeyes Priacanthus sp., Pristigenys sp.

- Butterflyfish Chaetodon sp.

- Clownfish Amphiprion sp.

- Groupers Serranus sp., Anthias sp., Caesioperca sp.

- Hake Urophycis sp.

- Moorish Idol Zanclus canescens

- Pinecone fish Monocentris japonicus

- Rockfish Sebastes sp.

- Squirrelfish Holocentrus sp. Sargocentrum sp.

- Scorpionfish Most species, but less common with lionfish (Pterois sp.)

- Whiptails Pentapodus sp.

- Wrasses Labridae sp.

Sunken eye

This is a condition known as enophthalmia, and is the reverse of exophthalmia. In captive fishes, it is almost always caused by severe dehydration experienced by fish exposed to a sudden rise in the salinity of their water. In this case, the problem is always bilateral – affecting both eyes equally. Rarely, mechanical damage resulting in the puncture of the eye globe itself will result in the deflation, or enophthalmus of just one eye.

Supersaturation

Typically, this is caused by an air leak developing on the suction side of a pump, a sump that is allowed to “catch air”, sometimes combined with water being pumped back into the aquarium without sufficient surface agitation. There is no cure for this problem other than to rectify the cause of the supersaturation and offer the fish time to recover on their own. Public aquariums may have the ability to hold the fish in pressurized chambers or deep aquariums (see sidebar). This can recompress the gas and if slowly depressurized, return the fish to normal condition.

Some fish develop a mild case of bilateral exophthalmia, and then never have the problem get any worse – even after years in captivity. The initial cause of this is unknown, and it is also not known why the problem never progresses to create any serious issue with the fish. Basically, a long-term captive fish, (very often a clownfish, grouper, triggerfish or angelfish) will slowly develop a minor case of popeye to a certain point, and then never have the problem get any worse, and it may do fine for years afterwards. The symptom is often so minor that it often cannot even be detected unless the fish is compared to normal (wild) specimens. Speculation as to the cause of this includes; dietary issues, chronic fish tuberculosis (Mycobacterium marinum and related species), minor mechanical trauma and even simply old age.

Vitamin and dietary deficiencies

While deficiencies in certain vitamins have been reported to cause eye problems in fish (Hemdal 2006) in most of these cases, the problem can only be demonstrated in the laboratory when fish are fed diets completely lacking in certain nutrients. Aquarium fish that are being fed at least a relatively rounded diet will not show these extreme symptoms, and thus dietary causes of blindness are quite rare.

Riboflavin (vitamin B2) and Vitamin A are both important for the continued eye health and proper vision in fishes. However, Vitamin A is a fat soluble vitamin, and artificially high doses can be toxic to fish. Remember that supplementing these vitamins will not cure eye problems in fish that were initially caused by another factor. Two vitamins that sometimes are deficient in aquarium fish diets are thiamin (vitamin B12) and -tocopherol (vitamin E) – but these are not implicated in eye problems.

Fish Eyes in Photographs

Many aquarists have discovered that it can be very difficult to successfully photograph certain species of fish when using a flash on their camera. The “Red Eye” effect is a common problem when using a flash to photograph people. If the light from the camera’s flash is parallel to, and very close to the line of sight of the camera lens, the blood in a person’s eye will reflect the flash’s light and make their eyes look red in the resulting photograph. Some cameras try to compensate for this by sending out a “pre-flash”. This causes the pupil of the subject’s eye to contract a bit, reducing the amount of red coloration. Because fish do not have the ability to quickly reduce the size of their eye’s pupil, this “red-eye reduction” method does not work for them. Additionally, the reflective color in a fish’s eye isn’t red, but is more often a very obtrusive green, white or silver. This means that software designed to automatically remove any residual “Red-Eye” in humans will not improve the photograph of a fish. There are only three possible solutions to this problem; photograph the fish using ambient light alone, moving the flash farther away from the horizontal plane of the camera lens by using a sync cord, or removing the aberrant coloration during post-production, using a software program where you replace the glowing orb with a more natural dark spot. For some reason, this “eye shine” is much more commonly seen in photographs of certain predatory fish. Three very difficult fish to photograph without having undue eye shine ruin the picture are walleye, (Sander vitreus) tarpon, (Megalops sp.) and the Pirarucu, (Arapaima gigas).

Never use a flash to photograph fish while they are restrained in a small container, or to photograph a fish within a day or so of it being acclimated to a new aquarium. Some fish are more affected by camera flashes than others – and you want to make sure that these sensitive fish have the ability to move away from the flash – also giving you the hint that you should stop photographing them. While actual damage to fish startled by a flash is rare, it is always a good idea to aim the flash away from the fish and fire it off a few times to give the fish a chance to become accustomed to it. Not all fish are bothered. During one photo session, a juvenile African angelfish in a tiny quarantine cubicle was absolutely fearless – it would approach the camera flash and try to bite at it through the tank wall.

Eye-Droop in Arowana and Arapaima

One affliction of fish seen mainly in public aquariums (and a few larger home aquariums) is “eye-droop” in the Osteoglossids – the bonytongues (Arowanas and their relatives). Basically, one or both of the eyes of the fish begin to point downwards, as if the fish was scanning the floor of the aquarium below it. This symptom is chronic, and rarely if ever resolves on its own, and sometimes gets worse over time.

This issue is seen most frequently in Asian, and silver arowanas as well as in Arapaima gigas. But that also happens to mirror the types of bonytongues that people tend to keep in aquariums. The causes for this syndrome may be multivariate, (as with head and lateral line erosion) the following are some proposed causes of this malady (from various sources):

- The eyes become “stuck” due to looking downwards for food

- Fat deposits behind the dorsal orbits of the eyes

- General poor nutrition

- Inbreeding depression (genetic deformity)

- Mechanical trauma

- High general stress levels in the fish

- Over-exposure to light

- Keeping the fish in tanks with clear sides

- Mycobacteriosis – fish tuberculosis

Of this list, numbers 5 and 8 cause this problem in most, if not all of the fish that have had authenticated reports for. In fact, these two causes are actually related to each other; droop-eye seems often to result from mechanical damage when the fish runs into the sides of the tank or the lid.

Arapaima with drooping left eye – notice the damage to jaw on the same side – indicating mechanical injury was likely the cause.

One reason that mechanical damage is a likely cause is due to the number of fish seen in which only one eye is affected. One would think that diet problems, inbreeding, light, stress, etc. would affect both eyes about equally, and there would be few, if any cases of single eye-droop. Finally, there is first-hand knowledge that eye-droop was caused by trauma in one case with an Arapaima. An adult Arapaima on exhibit at a public aquarium had no history of problems with its eyes. It was observed by the author to crash into the tank wall when it got spooked by a pacu. Later that day, its left eye was drooping. As of today, it still has the eye-droop in the left eye, while the right eye is still fine.

Public aquarists have long known that big arapaima and arowana become “flighty” at night. It is probable that all we are seeing with this syndrome is mechanical damage from smacking into the tank walls or lids. The same thing may be the cause of the “daffy duck” syndrome in big Pimelodid catfish (where their bills get bent up, down or askew). It all has to do with a combination of tank size, fish mass, instigating factor and if the tank has clear sides or not. Small fish don’t have the body mass to hit the wall with enough speed to cause droop-eye. Large fish kept in overly small tanks might not have enough running room to get up enough speed to cause damage. Big fish in big tanks can reach enough speed to die outright from hitting the tank sides at night (this has been shown in subsequent necropsy of young adult Arapaima) There is then the idea that some of the fish in the “middle” have just the right combination of body mass and “running room”, and get damaged when they hit the tank side, and their eyes droop as a result. In mild cases, one eye droops, in severe cases, or in cases of multiple impacts, both eyes are affected. Many people have reported that when kept in ponds or pond-like tanks, the problem is not seen. The theory is that these fish can more naturally navigate in ponds and streams, and can better avoid “hitting the wall”.

Some “cures” for droop-eye have been suggested over the years. One interesting suggestion is to float red ping pong balls (why red?) in the aquarium. The idea is that the fish will turn its eyes upwards to watch the floating ball, and cure itself. Many Asian arowana breeders advocate moving the affected fish to outdoor ponds. This obviously goes along with the observation that these species rarely if ever develop eye-droop while kept in ponds. There are also a few reports of surgery being performed to correct the problem, but as tantalizing as this sounds, there are never any details as to how such a surgery might be performed. That all said, there was a recent report from a British aquarium in which necropsies showed fat build-up (steatitis) behind the eyes of affected fish. Further study is needed here; unaffected fish need to be examined for the same fat build-up, and then there is still the question why are some fish only infected in one eye.

Blindness

A very common symptom reported by home aquarists is that one of their fish has become blind. This, more often than not, is a result of a fish becoming ill to the point that it is moribund (close to death) and is not just blind. Basically, a fish that bumps around the aquarium, running into the tank sides and ignoring food may not be blind at all, it may just be dying. A truly blind fish will behave as if it is night, and may even show its nighttime coloration. The fish will swim very cautiously, so as not to run into obstacles, and it will orientate itself in the normal upright position, and if food is added to the tank, it will attempt to seek it out, perhaps by moving its mouth along the bottom of the tank, snapping up any food that it may come in contact with. It is important for the aquarist to be able to differentiate between the subtle differences between these two problems as a truly blind fish may live for many years given extra care, while a moribund fish will continue its

health decline and soon die if the problem is not corrected.

Bright aquarium lighting is sometimes implicated in causing blindness, especially in lionfish (Pterois sp.). Only anecdotal reports of this are available, and since aquarium lighting is many times less intense than on tropical reefs, cause and effect cannot be linked. Feeding freshwater fish to marine predators (again – often lionfish) are also reported by home aquarists to cause blindness. In these cases, it is most likely that the predator has developed fatty liver disease, and the fish has become moribund from that.

A Diagnostic Key to Fish Eye Problems

The following key can be used by aquarists to evaluate problems they may have with their fish’s eyes. To use this key, just answer each question and then proceed to the next question as directed. If you are unclear of any answers, try following the key through both branches and see if one result is a better fit for your fish’s problem.

- Assuming there are a group of fish in the aquarium, is more than one fish affected? If yes go to # 2, if no go to #6. If the fish is being housed separately, you may need to explore both options to see which is a better fit.

- Was the development of the eye problem rapid, involving many fish, typically with bilateral retrobulbar exophthalmia and possibly air bubbles visible in some of their eyes? If yes, go to #4, if no go to #3

- Are the corneas of most fish clear? If yes, go to #4, if corneas are cloudy, go to #5

- This may be a case of acute supersaturation of atmospheric gas in the fish’s bloodstream.

- Many fish in an aquarium, all with cloudy eyes, typically is a sign of a widespread infection – see disease section.

- With only one fish being affected, the problem is either just starting, or it will be limited to that individual. Is the fish a Syngnathid? (Seahorse, pipefish or seadragon). If so, got to 7, else go to 8.

- Gas Bubble Disease (GBD) is a possibility.

- Only one fish is affected, does it have exophthalmia in both eyes? If so, go to 10, if only in one eye, go to 9. If the fish does not exhibit exophthalmia, go to 11

- Commonly, exophthalmia that develops in one fish, in only one eye is a result of physical trauma.

- Mild bilateral exophthalmia in one fish can have many causes. Review the fish’s history for possible infection-associated problems. In some cases, the cause cannot be determined; therefore no treatment can be suggested.

- Does the fish have the main symptom of not being able to see properly? If so, see the section on blindness, else go to 12.

- The remaining eye problems are typically chronic conditions such as cataracts and droop-eye for which there is no effective treatment.

Under Pressure!

A jury-rigged pressure tank used to re-pressurize fish to reduce popeye and air bladder over-inflation problems.

Some public aquariums have deep exhibits (> 15 feet deep, or about 1 ½ times atmospheric pressure) in which they can submerge fish suffering from gas produced exophthalmia. This can reduce the size of the gas bubbles, and allow them to dissolve back into the fish’s blood stream. The fish can then be brought slowly to the surface and the symptoms may be resolved. Other public aquariums have developed pressure chambers that can be used to reduce the size of any air bubbles that are causing exophthalmoses in fishes (A rudimentary one is pictured). Although the construction of these units is within the scope of many home aquarists, there is great danger working with pressure chambers such as these if they are not designed well, as they can explode causing injury to the aquarist. If you do decide to try this method, never work at pressures greater than one atmosphere (1 atm) above ambient (around 15 psi). The basic process is the affected fish and some aquarium water is added to the chamber, and it is compressed to 1 atm using pure oxygen. Never use compressed air to do this, as the fish needs the supplemental oxygen during the 18 to 24 hours it will need to remain compressed. Once the symptoms have been resolved, the pressure is gradually reduced back to ambient levels, over six to eight hours.

Conclusion

Aquarists need to inspect their fish closely every day, for signs of impending health problems. It is much easier to resolve a problem when it first starts, than to attempt a drastic emergency treatment when the fish is close to dying. A fish’s eye is a natural focal point for an aquarist looking at their fish. Look for changes in the eye and then use the information in this article to predict a proper course of action. But please remember that although many observable problems with fish first show up as changes in their eyes, this is by no means always true. Therefore, examine the entire fish closely for any other subtle changes, as well as analyze its overall demeanor – how well it is feeding, how it interacts with tankmates, its respiration rate and if it is overall alert and active. An aquarist who is highly alert to health changes in their fish is always better able to resolve the problem before fish loss occurs.

Glossary

- Cataract

- A cataract is when a lens becomes opaque (often gray) and does not transmit light efficiently, and vision may be impaired. While not common, this condition can occur in fish. Causes include nutritional deficiencies and old age.

- Corneal ulcers

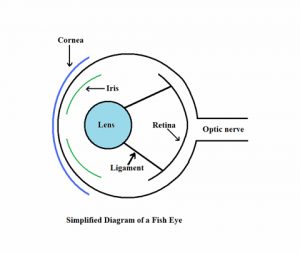

- The cornea is the clear, protective covering of the eye (the blue curved line in the accompanying diagram). When this membrane is damaged, an ulcer may develop. The damage can be caused by an injury, tankmate aggression or infection.

- Edema

- Fluid build-up in the tissues of the fish, often cause by kidney failure. Can cause mild to moderate bilateral retrobulbar exophthalmia.

- Enophthalmia

- The recession of the eyeball within the orbit.

- Enucleation

- Loss of the entire eye of the fish. Usually, this is a result of an aggressive act by another fish, actually biting the eye of a fish and removing it from its orbit. This problem can also occur from severe unresoleved exophthalmia, where the fish’s eye actually protrudes so far, that it is eventually lost. Assuming no secondary infection sets in, a fish that loses one eye can often recover, albiet with a diminished ability to navigate the aquarium and find food.

- Exophthalmia

- A bulging of the eye outwards from its normal position within the orbit. Exophthalmoses can be either bilateral or unilateral (both eyes or just one eye). As a symptom, it is commonly termed, exophthalmia or popeye.

- Intraorbital

- Within the orbit of the eye. Cataracts are an intraoribital condition.

- Retrobulbar

- Occurring behind the eye. A retrobulbar infection may create pressure behind the eye, forcing it out of its orbit.

Bibliography

- Hemdal, J.F. 2006. Advanced Marine Aquarium Techniques. 352pp. TFH publications, neptune City, New Jersey

- Hemdal, J.F. 1986. The Flashlight Fish. Freshwater and Marine Aquarium Magazine 9(11):29.

- Stoskopf, M.K. 1993. Fish Medicine. W.B. Saunders Co. Philadelphia, PA

Hi my fish somehow an eye and what I mean by that is that it has the protective film on top of it but it’s just empty I made a promise to the 4 fishes that live there that I would get a small tank so they could see at least one the outside since they have almost 8 years I think sadly one passed away that was the oldest one probably 2 years older than the other died didn’t know the problem he was I think the youngest one I just came home after school and he was floating didn’t move for a lot of time so I didn’t do what I promised and I feel very bad for it since I could do it anytime I just had to buy a mini aquarium so I was gonna do to the other 2 yellow and black and now my yellow one the one that doesn’t have an eye lost the only one that was left like the other just empty inside with the protection sometimes looks like he can see but sometimes it looks off like trying to eat the other one is a black fish that has the eyes out he can see a bit I can’t find anything related to a transparent eye could you pls help me?