Damselfishes (Pomacentridae) present a quandary for people involved in marine ornamental aquaculture. They are hardy, aggressive feeders that come in an impressive variety of brilliant colors and they are extremely popular in the marine aquarium hobby. However, despite the popularity of the entire family, only two genera of 28, Amphiprion and Premnas, have been cultured commercially. Attempts to rear species within other genera, including Pomacentrus, Abudefduf, Chrysiptera and Dascyllus, have met with little or no success to date. The reason for this is likely that their small size at hatching prevents them from accepting rotifers as a first food. I have been able to verify this hypothesis through my own experience while attempting to rear Chrysiptera paracema, Dascyllus trimaculatus, and Pomacentrus leucostictus. Dascyllus albisella and D. aruanus have been reared in the laboratory (Danilowicz and Brown, 1992), but not without the use of wild plankton. Although damselfishes account for almost half of the 20-24 million individual marine ornamental fishes traded annually (Wabnitz et al. 2003), their relatively low price fails to provide an economic incentive for aquaculturists and researchers to work toward overcoming the bottlenecks preventing their commercial production.

In the investigation described herein, eggs from a pair of Amblyglyphidodon aureus were collected from the living coral reef exhibit at Atlantis Marine World, a public aquarium in Riverhead, NY. Four separate spawns were collected, eggs were hatched, and larvae were reared with a success rate approaching 100%, using rotifers as a first food. These preliminary successes in rearing A. aureus suggest that members of this genus may be good candidates for commercial aquaculture.

Methods

In May 2006, six A. aureus were received as a donation from a hobbyist and placed in the 20,000-gallon coral reef tank at Atlantis Marine World. This was our first experience with damselfishes of this genus and our observations of their behavior in quarantine led to our decision to place them in the reef tank. Like Chromis spp. and in contrast to many other Pomacentrids, Amblyglyphidodon spp. are pelagic and gregarious, swimming out in the open in loose assemblages rather than aggressively defending a territory on the bottom. These characteristics make them much more suitable for a large community tank than many of their solitary relatives.

1 ½ inch PVC pipe with eggs from the first spawn. Eggs hatch in the evening under gentle aeration 5-6 days post spawn. Photo by Todd Gardner

In August 2006, while working on a piece of plumbing in the tank, an egg mass was discovered on a pipe near the surface. Observation later revealed one of the A. aureus defending it. We had no way of knowing how long the spawn had been there, but after two additional days, the eyes appeared to be well developed and we decided to remove the pipe so we could attempt to hatch the eggs.

The pipe was placed in a 29-gallon aquarium with natural seawater and the eggs were agitated with gentle aeration. Most of the eggs hatched on the second night after moving the pipe. Larvae were approximately 5mm upon hatching. Rotifers (Brachionus rotundiformis) were added and maintained at a density of 10/ml. Although the larvae were large and appeared to be eating rotifers immediately, my previous lack of success rearing other damselfish species prevented me from being overly confident and I decided to incorporate cultured copepods (Acartia hudsonica) into the daily feeding regime in addition to rotifers. The alga, Isochrysis galbana was maintained at an approximate density of 2×105 cells/ml for the first 10 days, after which time the tank was connected to the system. The rearing system consists of seven 29-gallon aquaria, a bio-filter and 40-watt UV sterilizer. Beginning on day 11, HUFA-enriched Artemia was introduced to the larval diet and became the exclusive food after a 3-day overlap with rotifers and copepods. Dry foods were introduced at day 20, however Artemia remained the primary food through day 50.

Around day 15, the larvae began to change in shape and behavior. They became more compressed, laterally and the body became noticeably deeper. The caudal fin also became slightly forked and small melanophores (pigment cells) began to appear. Larvae began associating with the bottom or some structure in the tank such as airlines and plumbing. Another distinct metamorphosis occurred around day 30 when the body shape deepened further and a sudden, drastic increase in melanophores resulted in the fish taking on a bright yellow color, virtually overnight. No mortalities were observed during the larval stage except for the 5 individuals sacrificed, weekly for photographing and measuring. The average growth rate of larvae for the first 30 days was approximately 0.17mm/day.

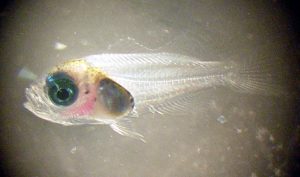

Larval A. aureus at day 12 post hatching. Note deepening body, differentiation of fins and the first appearance of pigment. Photo by Todd Gardner

Larval A. aureus at day 15 post hatching. The fins are almost fully developed. Photo by Todd Gardner

By day 30, post hatching, A. aureus has taken on the characteristic damselfish body shape. Photo by Todd Gardner

A. aureus at day 32. For me, the greatest reward for all my tedious labor in aquaculture is the sight of a tank filled with newly metamorphosed post-larvae. Photo by Todd Gardner

At day 60, these golden damsels could be considered market-size. Perhaps they will add a splash of color to our 80,000-gallon snorkel tank this summer. Photo by Todd Gardner

Their tendency to build nests on coral skeletons may make Amblyglyphidodon species a questionable choice for some reef keepers. Photo by Joe Yaiullo

Unfortunately, I must mention one negative habit of this mostly-reef-safe species. Although it is relatively peaceful for a Pomacentrid and does not have an appetite for desirable reef invertebrates, spawning pairs occasionally strip the tissue off part of an Acropora branch and use it as a nest site. This is not a problem in our 20,000-gallon reef tank, where an army of coral-eating fishes is no match for the growth of our scleractinians, however it’s easy to understand how a hobbyist with a small reef tank might not tolerate this behavior. I never asked the donor, but I can’t help but wonder if that has something to do with why we received the donation in the first place. The good news is, once a pair has decided on a nesting site, they usually stick with it. The pair that is responsible for the spawn shown in photo #10 has been using this site for more than six months without further damage to the coral. They may even help to protect the coral colony on which they spawn by keeping algae off the exposed skeleton, eating parasites, and chasing away coral grazers.

Three subsequent spawns have been removed, hatched, and reared since the original trial, all without the use of copepods, and all with survivorship approaching 100%. The ease with which A. aureus has been reared in these preliminary trials suggests that it may be a suitable species for aquaculture. We shipped part of the first brood to our friend, Bill Addison, owner of C-quest marine ornamental fish farm in Puerto Rico, so hopefully, captive-bred golden damselfish will soon be available in your local fish store.

Literature Cited

- Danilowicz, Bret S. and Brown, Christopher L. 1992. Rearing methods for two damselfish species: Dascyllus albisella and D. aruanus. Aquaculture 106: 141-149.

- Wabnitz, C., Taylor, M., Green, E., and Razak, T. 2003. From ocean to aquarium: The global trade in marine ornamental species. UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre. 65 pp.

0 Comments