By John Parkinson

I dove into the ocean and immediately regretted my decision. It was a hot day in June of 2011, and I was wearing too much neoprene. My SCUBA gear was appropriate for the rivers and quarries of the frigid northeast where I’d been working on my PhD, not the sub-tropical waters off the Florida Keys. The Gulf Stream Current keeps things warm down there, and that summer, submerging into the Atlantic felt like dipping into a hot bath. Thirty feet below the surface, the sun was still powerful, and I could feel the exposed skin on my neck starting to burn. I was uncomfortable, but there was work to be done, so I followed my guide over a moonscape of rippled sand dotted here and there with the odd rock. Panning my head left and right, I saw no fish, no lobsters, not even any seagrasses. But off in the distance, emerging from the blueness at the edge of my vision, rose a single vertical spire. I’d soon learn that it was teeming with life.

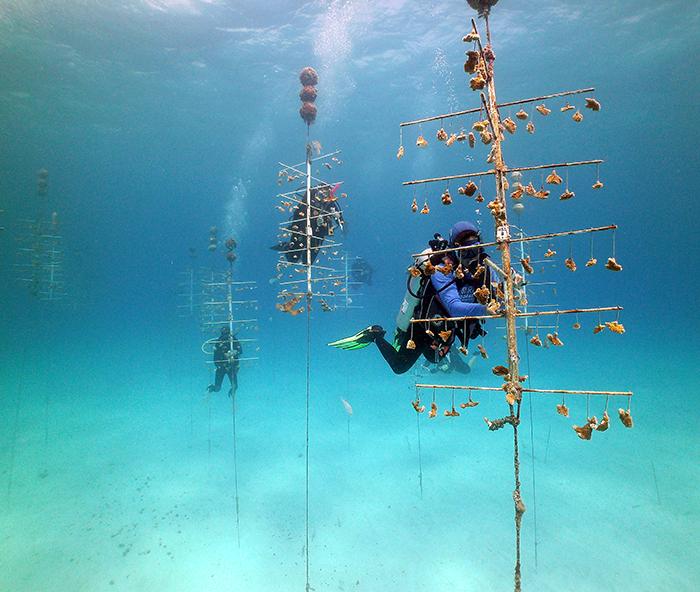

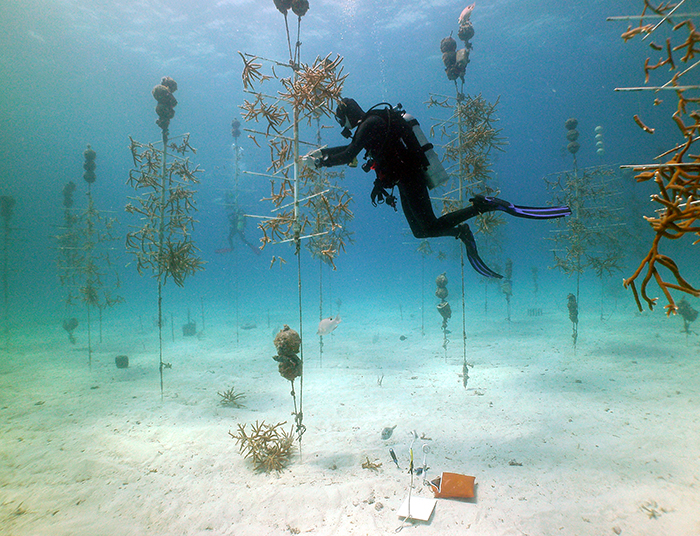

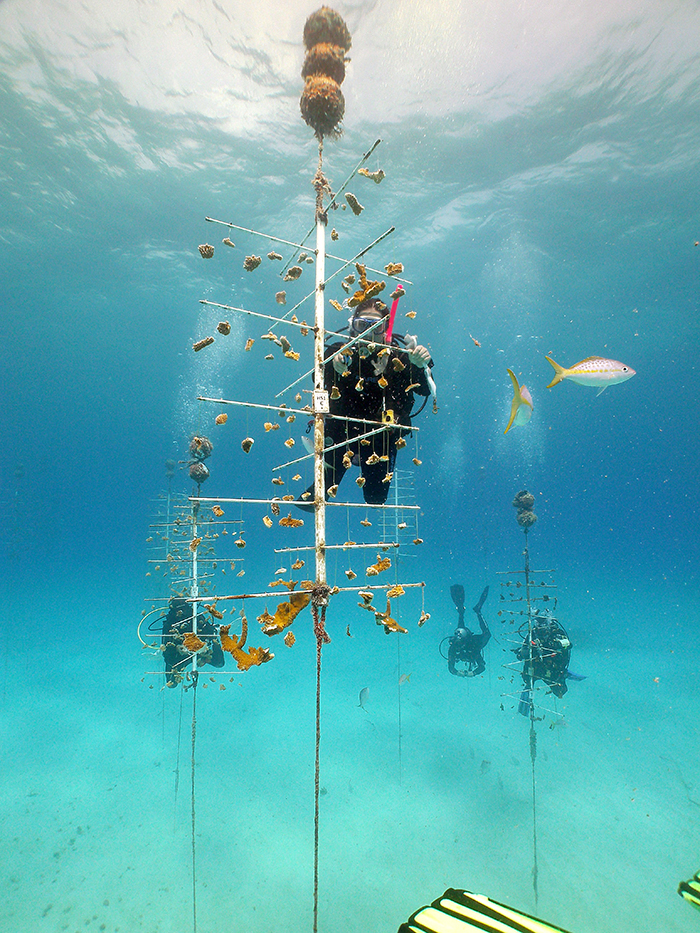

As we swam closer, the shape resolved into a floating, tree-like structure attached to the sea bed by a long tether. Its central trunk was composed of PVC with fiberglass poles branching out at right angles. From each branch, swaying slightly in the current, hung orange fragments of the threatened Staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis). They had been sliced and diced and strung up like ornaments, yet each one appeared healthy: thick skeletons, bright colors, extended polyps, and no signs of disease or predation or bleaching. A few feet away, I could make out another tree, and beyond it, another. Evenly spaced and arranged in rows, there were more than twenty total, each supporting fragments from a unique coral colony. Ken Nedimyer, my guide and the founder of the non-profit Coral Restoration Foundation, had “planted” these trees in his nursery several years earlier. The goal was to grow coral tissue as quickly and efficiently as possible for use in restoration projects.

That dive was my first introduction to coral gardening, but you may already be more familiar with the technique than I was at the time. The same principles are at play in the aquarium trade. If you maintain a tank and have ever pruned back a growing colony, you’ve already performed coral gardening. Because corals are clonal organisms, these clippings are perfectly capable of surviving on their own. Rather than let them go to waste, you have the option of bringing them to a frag swap, perhaps trading them for someone else’s clippings and returning home with a new coral for your display. These frag swap events spread different corals throughout the trade, and acts as a type of insurance; if any one tank fails, that coral is likely still alive in another. It’s a fairly easy way to spread risk.

Coral gardening is a frag swap on a grander scale. Instead of providing insurance for tanks, it does so for entire reefs. Here’s the basic premise. Divers collect fragments from large donor colonies found in the wild. The fragments are brought back to the nursery, which is typically located in a sand patch with a wide buffer zone and relatively stable temperatures. The coral pieces are attached to support structures such as Ken Nedimyer’s coral trees, where they are left to grow for months to years. Divers will periodically visit the nursery to clean the supports, check the health of the colonies, and re-frag, constantly increasing the total amount of tissue in the nursery. Ultimately, the largest fragments are removed from the support and transported back into the wild, where they are cemented onto degraded reefs. Now a single colony that had previously been isolated in one location is spread out across multiple reefs.

Coral gardening has been around for a long time, but it’s become particularly successful in the Caribbean in the last decade, where a confluence of three factors sparked nursery development. The first ingredient was catastrophe. The most well-cited numbers are grim: 50% of coral reefs worldwide have been lost, with another 30% predicted to expire in the next thirty years. Those statistics are even worse in the Caribbean. I’ve heard a few researchers grudgingly characterize the region as “a bunch of slime-covered rocks” rather than a functioning reef ecosystem. That seems a touch pessimistic, but it’s an accurate representation of what will happen in a few years if we continue on the current trajectory. The reasons for coral decline are multiple: overfishing, pollution, coastal development, and thermal bleaching events related to climate change. Ocean acidification is taking its toll, as well. The two primary reef-builders in the area—the Staghorn and its sister species, the Elkhorn coral (Acropora palmata)—were nearly wiped out by disease outbreaks in the 1980’s, and are now protected by the Endangered Species Act. Because the Staghorn forms branching colonies that are easy to fragment, it has been the main focus of restoration, but progress is also being made on other species.

The second critical ingredient was government funding. In 2009, a portion of the money from the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act was set aside to develop existing coral nurseries in Florida. This major investment allowed the nurseries to expand from curiosities to fully-fledged restoration programs. As hobbyists, we tend to appreciate corals for their natural beauty and biology, but it takes more than that to convince the government to lay down cash. Fortunately, corals provide important ecological goods and services, and their value to humans is increasingly recognized by policy makers. Coral reefs provide coastal protection from storms and hurricanes, marine natural products, habitat for commercially and ecologically important fish, sustenance fishing, billions of dollars in annual tourism revenue; the list goes on. When reefs die, we feel it not only in our hearts, but also in our wallets.

The final ingredient was local knowledge and support. Given the collapse of many reefs along the Florida Reef Tract, scientists have been monitoring the area closely for a long time. Marine protected areas have been established to limit certain human impacts, and both government and university researchers have been tracking coral performance and identifying the links between stressors and degradation. A large network of concerned citizens has also developed, including SCUBA shop and other local business owners, fisherman, aquarists, and conservationists. Though nursery managers spend a good deal of time out on the water, they spend just as much on education and engagement, holding workshops, giving lectures, and networking with museums and aquariums to inform the public of their work. One could argue that the increased awareness that has resulted from successful restoration programs has done just as much good for the corals as the nurseries themselves, as more citizens are thinking twice about dropping their anchors on colonies, tossing their waste overboard, or using too much water in their homes.

So how effective are nurseries? They’re still in the early stages of development, so the data are just starting to come in. Only in the last few years or so has outplanting to different reefs been authorized by permitting agencies in Florida. Nevertheless, there are already success stories. For example, in the winter of 2011—just a few months before I first went diving at Ken’s nursery—a freakishly cold mass of water settled over the Keys and lingered there. The event decimated corals located in the shallows, which received the brunt of the cold. Many of the original donor colonies died, but their fragments in the deeper, warmer nursery survived, and have since been replanted back where they were originally thriving. They seem to be doing well.

Transplantation also enhances coral sexual reproduction, which has already been observed in the nurseries. Fragmentation is strictly asexual; if you start with one colony and break it in half, you now have two separate but identical clones. Corals can also reproduce sexually by releasing sperm and eggs into the water column during synchronized spawning events, which results in new individuals the same way that two human parents make a unique baby. Also like humans, for such events to be successful, corals need to be located near each other. As more colonies on a reef die, the remaining colonies have fewer opportunities to mix their sperm and eggs with those of other individuals. Transplanted corals can fill in these gaps. Because scientists can use molecular tools to tell which corals are unique, nursery managers can bring in specific colonies that are known to have different genetic backgrounds (that’s my part of the project, and why I got involved with the nurseries to begin with). This increases the extent of genetic diversity on a given reef, and may bring in new beneficial genes to the local population. The importance of genetic diversity in coral restoration merits its own article, but generally speaking, diversity is another form of insurance against future stressors, as it increases the likelihood that at least some colonies will survive.

Other benefits of transplantation are even more immediate. A reef with few corals attracts few fish. Loss of fish means algal overgrowth, since the herbivores aren’t there to clear away the algae. Algal overgrowth means less bare substrate for baby corals to attach to. Fewer baby corals means fewer adult corals, so as the older generation dies, there’s nothing to replace it. Then the reef has even fewer corals than it began with, which means fewer opportunities for successful sexual reproduction, lower genetic diversity, fewer fish, etc. The death spiral continues until all the corals and fish are gone, and along with them, the benefits they would have provided to both humans and nature. But the moment a coral is transplanted to a dying reef, there’s more habitat available for fish and better chances for reproduction, potentially stopping the spiral. While transplants won’t address the root cause of the reef’s decline, they may keep the ecosystem alive long enough for it to rebound.

Which leads to an important, final point. Coral gardening is not a long term solution to the problems that are plaguing reefs worldwide. Reducing carbon emissions, pollution, and destructive practices like port dredging will benefit more corals. Transplantation is a targeted approach that needs to be tailored to specific areas. The process is expensive and labor-intensive, and while early indications suggest great potential on the local scale, we are still data-deficient in many ways. It would be wrong for anyone to hold up these nurseries as proof that entire reef ecosystems can be successfully transplanted away from construction sites, and thereby use them to justify reckless destruction of healthy reefs. This turn of events tragically played out last year in a development project that shall not be named, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of coral colonies.

Around the world, great tracts of reef are expected to be lost this year, the hottest on record. Damaging El Nino/Southern Oscillation effects are contributing to the third major global bleaching event ever, which is ongoing and projected to continue well into next year. Because corals are out of sight and out of mind for many, it is difficult to gain support for their preservation. Any action we can take to protect colonies and educate the public is worthwhile. Coral nurseries, gardening techniques, restoration programs, and outreach may not fix everything, but they are certainly helping. So, too, is the aquarium trade, which brings these hidden treasures of the deep out into the open for more people to see. Next time you’re at a frag swap, I hope you’ll remember the bigger frag swap going on in the ocean, and maybe tell some of the other hobbyists you meet about it.

For further information, check out these websites (full disclosure: I’ve worked with all of these organizations in the past):

coralrestoration.org (Ken Nedimyer’s nonprofit nursery; if you’re interested in contributing, they have a successful Adopt-A-Reef fundraising program)

secore.org (SExual COral REproduction is a union of scientists and public zoos and aquaria trying to improve coral breeding programs)

rescueareef.com (a nursery run by the University of Miami; has a program where you can dive and help out on the nursery)

cnso.nova.edu/coralnursery (a nursery run by NOVA Southeastern University)

nature.org (nursery program maintained by the Nature Conservancy and MOTE Marine Lab)

0 Comments