By Randy Donowitz

For my latest installment of Did I Say That ? I dug up an article that was originally published in the 2005 Marine Fish and Reef USA Annual. Despite all the discoveries and advances in reef-keeping, this subject is still one of the most frustrating and commonly encountered setbacks in the hobby. Hopefully, the advise below is still useful.

Algae By Any Other Name

Of all the possible nuisance infestations that threaten the health of captive reef systems, outbreaks of red slime algae are among the most common and most pernicious. I have seen numerous novice aquarists leave the hobby due to the inability to control red slime outbreaks. Learning how to prevent and eradicate this most troublesome intruder is well worth the time and effort.

The term red slime algae is misleading in several ways and often leads to confusion among hobbyists. What we are really referring to is a form of cyanobacteria, an ancient bacterial life form that is thought to be an evolutionary link between bacteria and true algae. These bacteria cells exhibit several unique biological characteristics that bridge these two kingdoms. Like other bacteria, they lack fully developed cell structures, but like true algae they contain chlorophyll and other compounds that enable them to carry out photosynthesis as a primary means of sustenance. Additionally, cyanobacteria have the ability to pull dissolved organic compounds directly from the substrate and water column greatly enhancing their ability to thrive under a wide range of environmental conditions. This adaptability is what makes cyanobacteria so problematic to deal with in the aquarium.

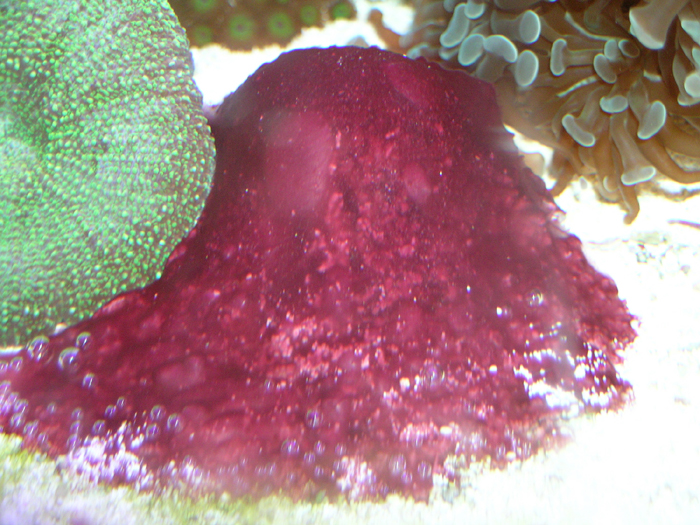

To further complicate matters for the novice, cyanobacteria are commonly known as blue-green algae, and in the aquarium, most often form slimy, stringy looking sheets that can spread rapidly to cover the sand, rockwork, and in severe cases the corals themselves. Patches can be green, brown, black, or red and almost always exhibit numerous air bubbles indicative of their photosynthetic capabilities.

So you see, red slime algae is neither algae, nor is it always red, but left unchecked, it is always a problem.

Why me? Why now?

It is quite common for cyanobacteria to bloom during the initial months of a system’s life due to the elevated levels of dissolved organics produced by curing live rock, combined with the limited capabilities of an immature filtration system. During this period it is rare to see red cyanobacteria, and the green or brown varieties that commonly develop seem to recede of their own accord as time passes and the system matures. To ensure that this is the case, it is always advisable to slowly stock the aquarium in order to avoid a too rapid introduction of nitrogenous waste into the system. This sounds simple, but it requires great restraint on the part of the aquarist who is anxious to move forward and build the reef of their dreams. Failing to do so greatly increases the chances of a severe outbreak of cyanobacteria and other nuisance algae.

Ironically, I find that the aquarists most susceptible to allowing cyanobacteria to take hold in their systems are beginners who don’t know better, and seasoned veterans who get lazy and let their husbandry practices slip. The latter is a particularly dangerous situation, because as a captive reef system ages, dissolved nutrients begin to accumulate in the rock and sand bed providing the ideal conditions for cyanobacteria to take hold. Like so many other areas of successful reef keeping, careful observation and sound husbandry practices are the keys to avoiding problems with cyanobacteria.

Cyanobacteria are present in all marine systems and are often visible in small patches in even the healthiest of systems. It is not uncommon for limited growth to develop in low current areas behind the rock structure, on internal plumbing, or curiously at the base of many species of leather coral. Aquarists should not be alarmed if they notice such developments, but they should keep careful watch and be ready to act if the situation seems to be worsening. Because outbreaks of cyanobacteria are almost always tied to an increase in dissolved organics in the system, it is wise to test the water parameters whenever new patches occur. What you should be on the look out for is an increase in Phosphate (PO4) and Nitrate (NO3) levels that are telltale signs of increased nutrients. If these levels are on the rise, you need to ask yourself why? Am I over feeding? Am I keeping up with my water change regimen? Is my source water contaminated? Did something die off? And finally, is the system overstocked? A yes answer to any of these questions has likely highlighted the root of the problem, and you need to take corrective action.

There is a lot of anecdotal evidence that light spectrum and intensity play a role in cyanobacteria blooms, and given their broad abilities to photosynthesize this should not come as a surprise. If you begin to experience signs of an oncoming bloom, it is wise to think about changing the lamps in your lighting system. Over the course of months, lamps tend to shift spectrum and clearly begin to lose intensity. From my experience, lighting is usually not the main culprit, but it is helpful to rule out as many contributing factors as possible.

If you catch an outbreak early enough, a series of partial water exchanges with RO/DI water and a good quality salt mix will usually do the trick. You should also try to siphon off as much of the cyanobacteria as possible. Remember, prevention is far preferable to the arduous and frustrating task of eradicating a full on cyanobacteria bloom.

Eradication Procedures

If you find yourself as I recently did (I’d become one of those lazy veterans) in the unfortunate situation where a cyanobacteria bloom is threatening to take over your captive reef, you must be prepared to attack the problem on several fronts simultaneously. Persistence is paramount as it may take weeks or even months of diligent attention to reverse the problem. The goal is to safely improve the water quality as quickly as possible, minimize damage in the interim, and prevent future outbreaks.

As a first step, I recommend a series of bi-weekly 25-30% water changes combined with a thorough siphoning off of as much of the visible cyanobacteria as possible. Overgrown rocks that are easily removed from the system can be scrubbed in a separate container and then replaced. You will also likely notice pockets of detritus near or underneath the cyanobacteria mats, and these should be removed as well. It is a good idea to use a turkey baster or small power head to blow detritus off the substrate where it can be easily removed by your system’s mechanical filter. You will more than likely have to repeat this procedure on a regular basis paying particular attention to cyanobacterial growth that is beginning to encroach upon sessile invertebrates. If you find recurring patches on areas of the sand or rocks that are not threatening any other organisms, I have found it useful to leave them be for a while. The mats then become thicker and after trapping enough of their own oxygen bubbles lift off the substrate intact facilitating easy removal.

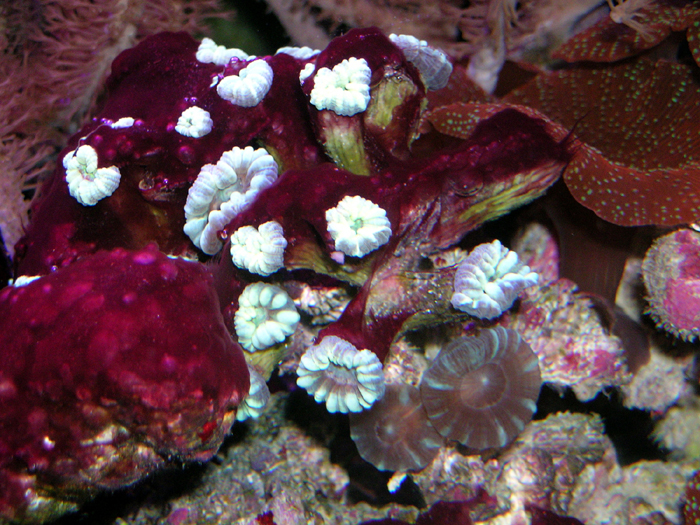

Caulestrea sp. coral being out competed by cyanobacteria growth. Siphoning the bacterial mat off the coral may allow it to be saved.

Next, I would take a close look at the equipment on your system. Make sure that the protein skimmer is clean and functioning properly. If you suspect that your skimmer is undersized for your needs, this would be a good time to upgrade, as protein skimming is one of the most effective means of improving water quality. If you run a skimmerless system, it might be wise to employ one until the bloom is under control. I would also clean the circulation pump(s), and perhaps upgrade the circulation in your system as this will help eliminate dead spots and prevent detritus from accumulating on the substrate. I’d also take a look at the detritus level that may have accumulated in your sump. If it is appreciable, siphon it out during one of the water exchanges. Just to be sure, I’d also change the resins in your RO/DI system to ensure the purest possible water for exchanges and top off.

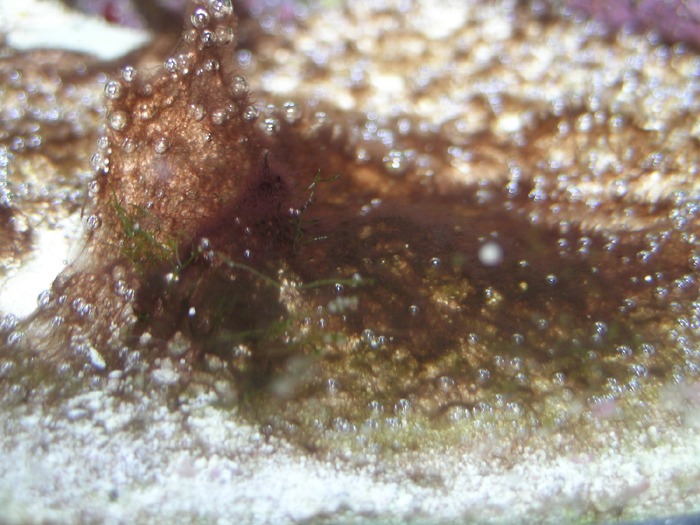

Cyano bacteria typically traps oxygen bubbles in its tissues. As growth develops, these bubbles begin to lift the slime mat off the substrate, facilitating easy removal.

In order help reduce the nutrient levels in the system I would change the carbon frequently—every other week—and seriously consider adding a small reactor with some of the iron based phosphate removing media that has recently become available. This method of phosphate removal is superior to the traditional aluminum based products and will bring down phosphate levels quickly and safely. I would also begin using calcium hydroxide (kalkwasser) drips to help bind phosphates and enhance skimmer performance. A side benefit is that you will also be boosting your calcium and alkalinity levels at the same time.

There are very few animals that eat cyanobacteria, but some species of reef safe snails and hermit crabs will consume it, as will queen conch, and some sea hares. In my experience, these animals are welcome additions to a captive reef and aid in preventing cyanobacteria and other nuisance algae from taking hold, but they will not be able to eradicate a full on outbreak. Once your situation is under control, you might want to increase the number of these animals in your system as a safeguard for the future.

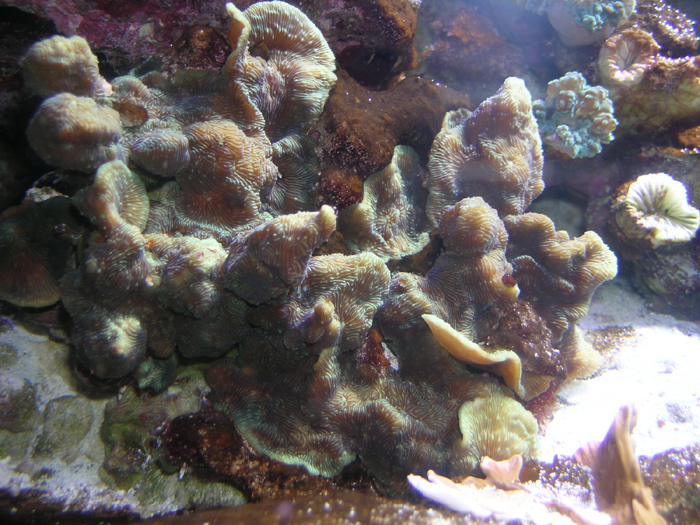

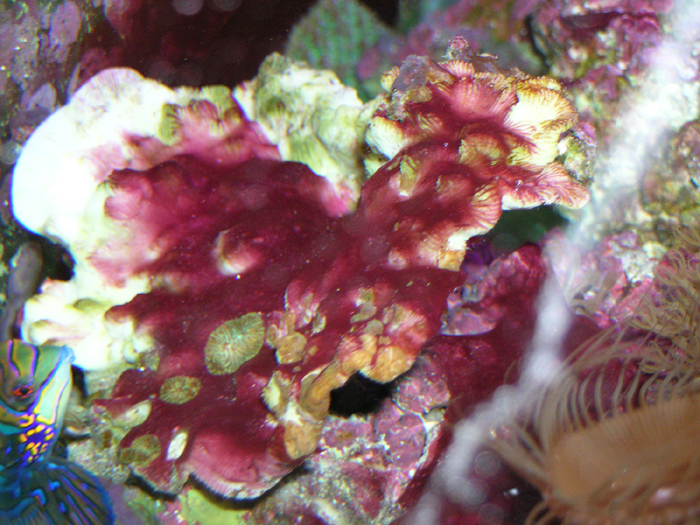

Even well established thriving reef systems, like the one pictured here, can develop outbreaks of Cyano bacteria. This is most likely when sound husbandry practices are neglected.

Finally, if you are truly desperate and cyanobacteria are threatening to choke out your whole system there are several red slime eradicating products available that are reportedly effective and relatively safe. Most contain antibiotics like erythromycin that do not discriminate between types of bacteria, so you will lose some of the good along with the bad. Another consideration is that bacteria quickly become resistant to antibiotics and subsequent treatment, if necessary, may be less effective. I like to think of this option as a last resort and one that can be avoided if you diligently follow the recommendations outlined here.

0 Comments