Any serious aquarist knows that maintenance of a successful aquarium requires a fair amount of time and effort. And most would acknowledge that, from time to time, constraints on our ‘free’ time make us prioritize other things. Sometimes the maintenance schedule for an aquarium slips down a notch or two – a water change will not be performed, activated carbon will not be changed, and so on. Most likely, this will not result in disaster. However, chemical and physical processes in the glass box will continue, resulting in degraded water quality. One noticeable result of deferred maintenance is the aquarium’s water becoming yellow. This is a result of decaying algae (particularly brown alga), decomposing animal wastes, uneaten food, etc., dissolving into the water. Technically, yellow water is referred to as ‘water color’ and can be reliably measured in freshwater or seawater.

Looking downwards into containers of yellow aquarium water (left) and fresh artificial sea water. The yellow water can potentially affect photosynthesis and coral coloration in a negative way.

Why might color of water be of importance to hobbyists? Aside from aesthetics, color is known to preferentially absorb certain light wavelengths, such those in the bandwidths we call violet and blue. These bandwidths are important in the promotion of photosynthesis – something we strive for in planted freshwater aquaria as well as coral reef tanks. We also know that these light bandwidths are crucial in promoting the brilliant colors (both fluorescent and non-fluorescent) in many coral specimens. Could yellow water absorb enough violet and blue light to hinder photosynthesis or prevent production of brilliant coloration in corals? This article will describe how experiments were conducted, and report conclusions on this matter.

Definition of Attenuation

For our purposes, attenuation is defined as “loss of energy suffered by radiation as it passes through water as a result of absorption or scattering.”

Attenuation of Light by Yellow Aquarium Water

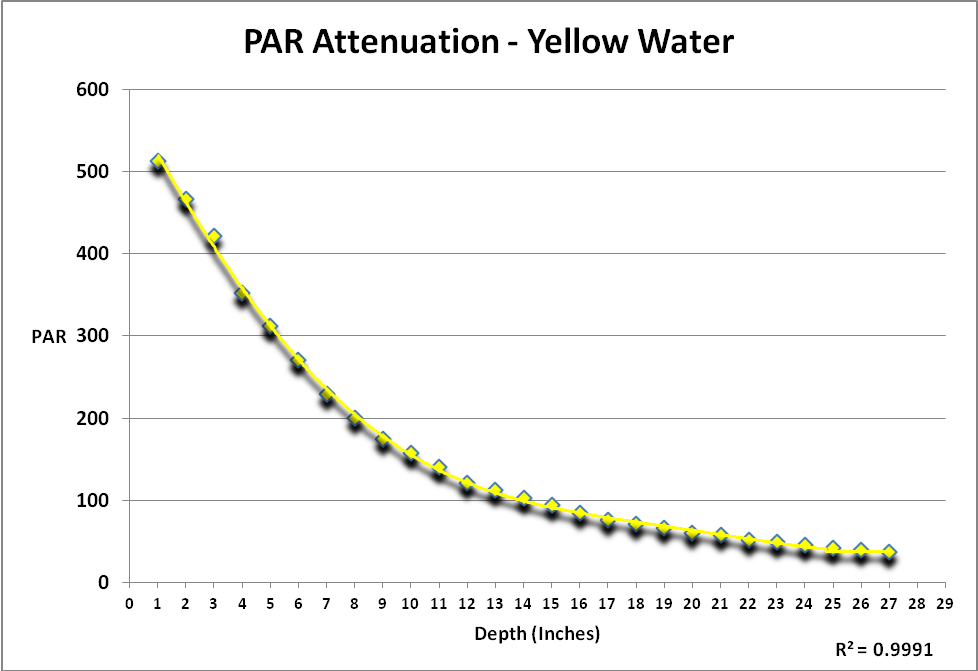

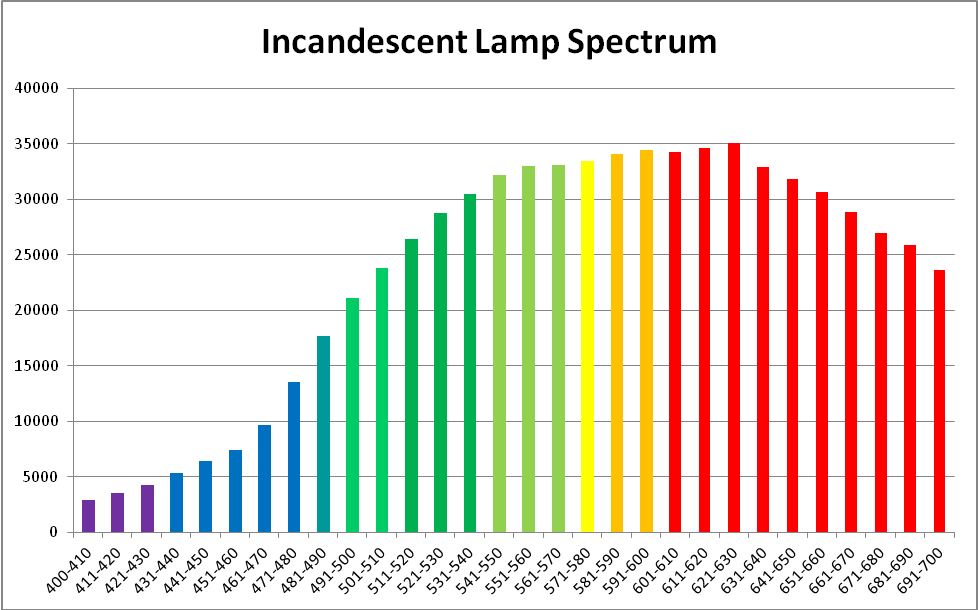

Light is described as those wavelengths between 400 and 700nm (visible light). Measurements of PAR (Photosynthetically Active Radiation and reported as PPFD – Photosynthetic Photon Flux Density – as µmol·m²·second) and spectral qualities were made immediately above and below the water’s surface and then every 2 inches thereafter, up to a depth of 26 inches.

Figure 1 shows attenuation by yellow water of light produced by an incandescent lamp. The procedure generating these results was repeated in ‘clear’ sea water. Since the protocol could not be repeated exactly, a simple comparison of the two data sets of PAR would not tell the story. See Protocol section below for details.

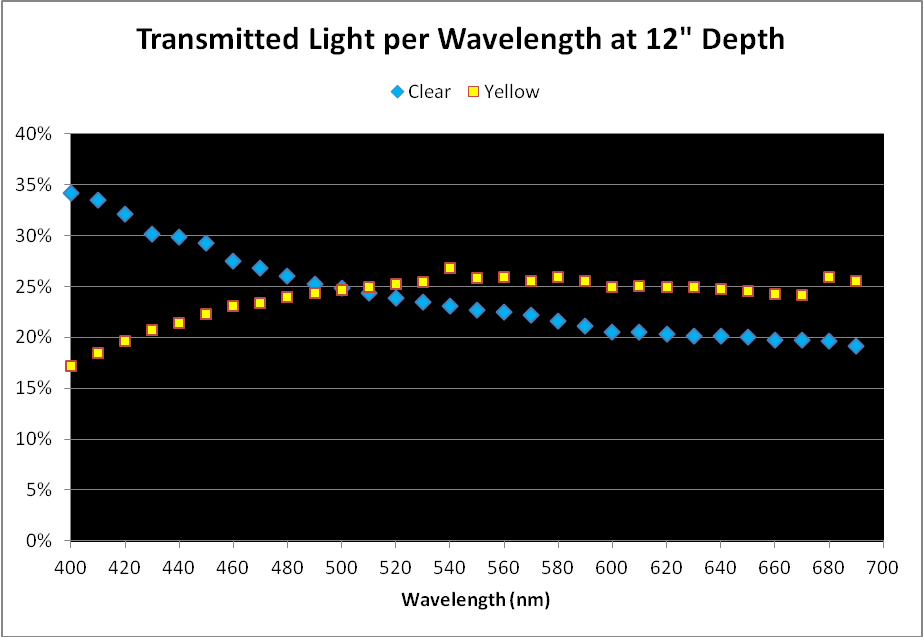

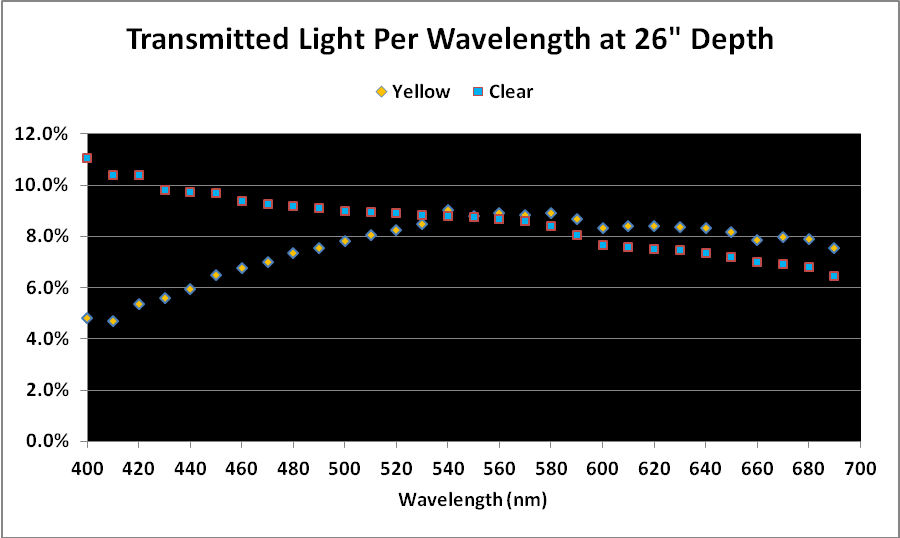

Figure 2. Comparison of light transmission by wavelength in 12″ water columns of ‘clear’ and ‘yellow’ waters. Percentages are based on light quality just below the water’s surface and at 12″ depth.

Comparison of Light Quality as a Percentage

As mentioned above, a simple comparison of PAR transmitted through the ‘yellow’ and ‘clear’ water samples did not yield meaningful results, although it could be used in further calculations.

When we examine the amount of light transmitted per bandwidth (expressed as a percentage), trends emerge. See Figures 2 and 3.

Discussion

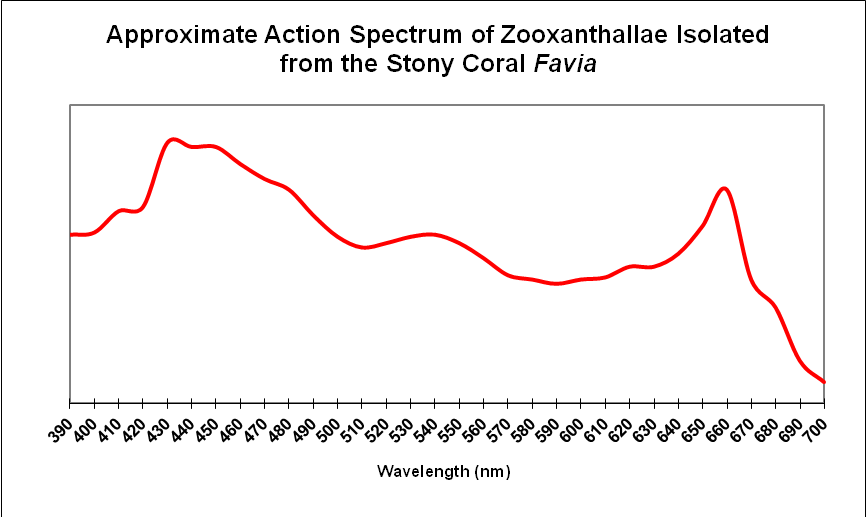

Results demonstrate that yellow water can strongly absorb violet and some blue wavelengths even in shallow water seen in aquaria. These wavelengths are important in the promotion of photosynthesis and coral fluorescent and non-fluorescent coloration. See Figure 4 for the absorption spectra of zooxanthellae isolated from the stony coral Favia.

Table 1 lists the wavelengths used by researchers to induce the expression of fluorescent proteins in corals. If this list were to be complete, it would likely state that blue/violet light is responsible for coloration (both fluorescent and non-fluorescent) in hundreds of corals. Bear in mind that violet/blue light is also responsible for excitation of many coral fluorescent proteins.

Figure 4. Zooxanthellae strongly absorb blue and red wavelengths. Yellow water can preferentially absorb violet and blue wavelengths.

| Host | Protein | Activator | Direction | Shift |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acropora millepora | amilFP513 | UV-A | Reversible | 2-fold Increase in fluorescence |

| Acropora millepora | amilFP594 | Blue light @ 488nm | ? | Red to Green |

| Aequorea victoria | GFP | Anoxic/anaerobic Conditions/Blue light | ? | Green to Red |

| Anemonia sculata | “Kindling” Protein | Green Light (540-560nm) | Reversible/Irreversible | None to Red |

| Dendronephthya sp. | Dendra | Blue Light @ 488nm | ? | Green to Red |

| Dendronephthya sp. | DendFP | UV-A at 366nm | Irreversible | Green to Red |

| Discosoma | DsRed | Exposure to light at ~ 488nm | ? | Green-blue to Orange |

| Discosoma | DsRed | Exposure to light at ~570nm | ? | Red to Super Red |

| Favia favus | Kikume | UV & Violet (350-420nm) | ? | Green to Red |

| Lobophyllia hemprichii | Eos | UV @ 390nm/Violet Light ~400nm | ? | Green to Red |

| Montastraea annularis | * | UV/Violet Light | ? | Green to Red |

| Montastraea cavernosa | mcavRFP | UV – Violet Light | Irreversible | Green to Red |

| “Pectiniidae” | Dronpa | ~490nm to bleach | Reversible | Green to None |

| Ricordea florida | rfloRFP | UV/Violet Light | ? | Green to Red |

| Trachyphyllia geoffroyi | Kaede/tgeoRFP | UV – Violet Light (350-410nm) | Irreversible | Green to Red |

Figure 5. Sometimes science just ain’t pretty. The sliding jig holds the spectrometer patch cord, Spectralon reference, and quantum sensor. The incandescent lamp is held in place by another jig.

Yellowing of aquarium water can occur due to poor maintenance practices. It is well known that some lighting sources (metal halide and fluorescent lamps) lose intensity as well as spectral qualities (especially in the violet and blue ranges) as they age. In a poorly maintained aquarium, an aged lamp(s) with low production of violet/blue light combined with increasing yellow water (absorbing more of these wavelengths) could result in problems for some corals. It is possible that the preferential absorption of violet and blue light by yellow water could impact the coloration and health of symbiotic invertebrates, especially when conditions such as spectral quality and intensity were marginal to begin with.

For those interested, a detailed account of determination of light qualities, water color, and suspended solids follows.

Experiment Protocol

Fifty-five gallons (US) were transferred of water were transferred to a 60-gallon black polyethylene drum. The top of this drum had been removed to allow access. A specially built jig made of PVC and CPVC pipe held the spectrometer’s patch cord at a 45 angle to a Spectralon 99% diffuse reflectance standard (Labsphere, Sutton, New Hampshire, USA) as well as the Li-Cor quantum sensor. The PVC pipe was held snugly in place when it penetrated a hole in a piece of 2″x4″ lumber. This friction fit allowed the assembly to be raised and lowered in the drum. Alignment was maintained by reference marks, and the vertical pipe was marked in 1″ increments. See Figure 5. This procedure was conducted at night, with the only light being supplied by 200-watt incandescent lamp and was used in testing the ‘clear’ and ‘yellow’ waters.

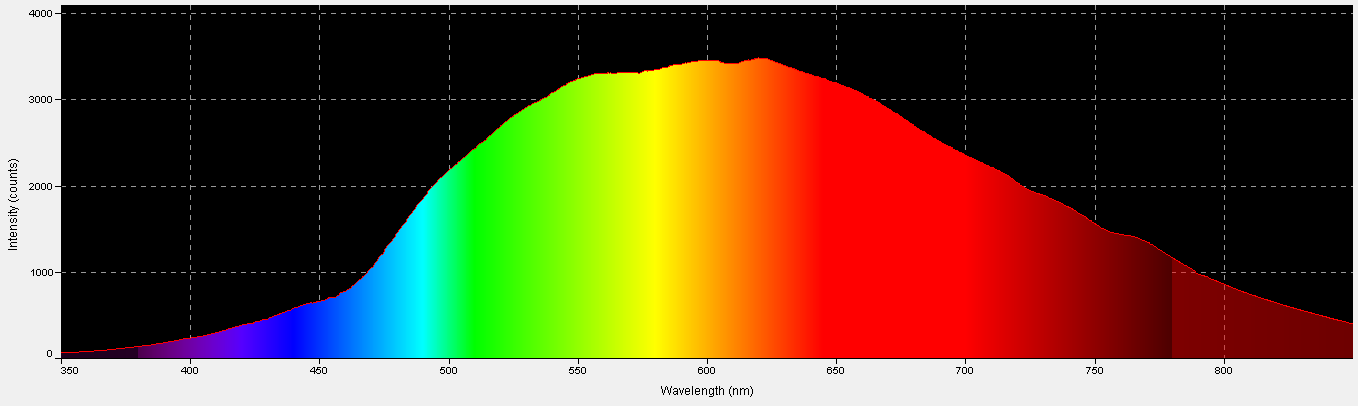

Figure 6. Spectral quality of the incandescent lamp. This graphic was generated by Ocean Optic’s SpectraSuite software.

Clear water (freshly mixed Instant Ocean dissolved in tap water treated by reverse osmosis, followed by filtration by a Marineland Magnum canister filter equipped with a 8-micron cartridge) and yellow water were tested for suspended solids, volatile suspended solids, and turbidity. In addition, light transmission was measure through a water column and PAR measurements were made at two inch increments. PAR values were determined with a Li-Cor LI-1400 data logger (Lincoln, Nebraska, USA) equipped with an underwater 2-pi sensor. ‘Air’ and ‘water’ calibrations of this instrument were used where appropriate. Spectral characteristics were determined with an Ocean Optics (Dunedin, Florida, USA) USB2000 spectrometer. The readings from the spectrometer were corrected for ‘electrical dark’ and recorded after 50 averages were made. These data were processed by Ocean Optic’s SpectraSuite software, and exported to MS Excel for further analyses using proprietary programming.

Water in an aquarium was allowed to age for several months without benefit of filtration (other than nutrient control by several clumps of Chaetomorpha alga in a sump), resulting in water distinctly ‘yellow’ to the eye.

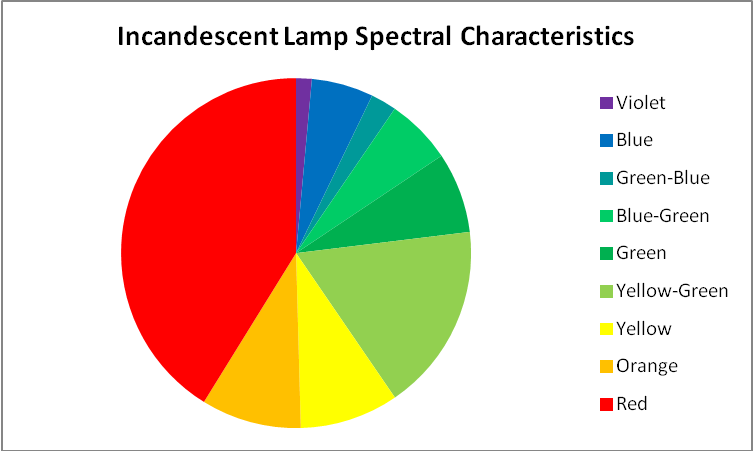

An incandescent lamp provided light in the experiments and was chosen since its characteristics lack spikes. See Figures 6, 7, and 8.

This tedious process was repeated for the ‘clear’ and ‘colored’ water samples’ data in increments of 2 inch depth. Tabular data from the spectrometer and SpectraSuite software were exported to MS Excel where light intensities per 10nm bandwidths, percentages, and others were calculated.

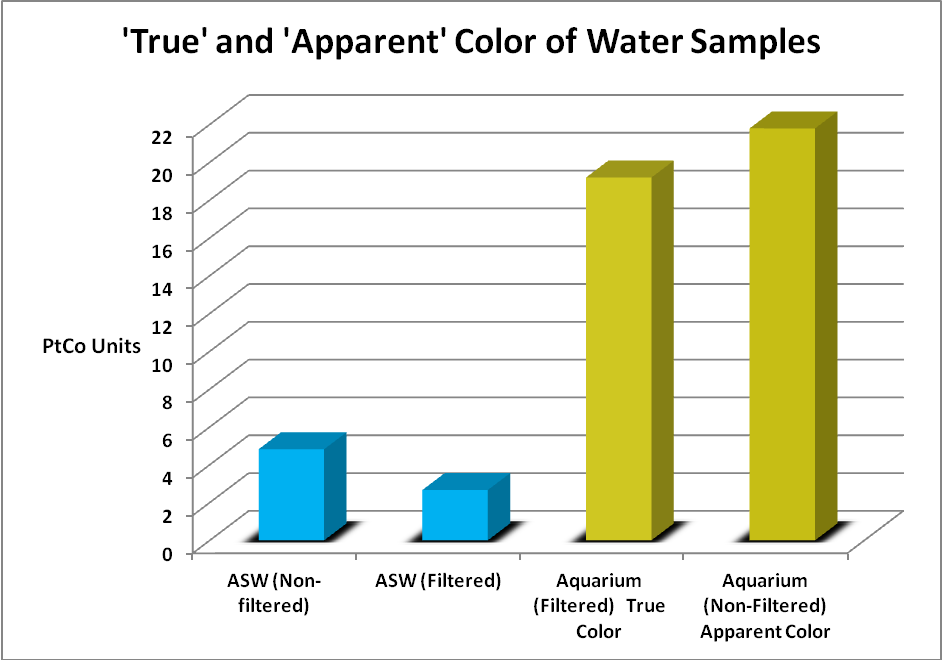

True and Apparent Color of Water Samples

Color of water (or yellowness) can be measured by a comparator, colorimeter, or spectrometer. The scale is 0 -500 platinum-cobalt units. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater (1998) describes the following methods for determining true and apparent color of water. Apparent Color describes color of an unfiltered sample, where suspended matter affects the measurement. True Color is determined after this matter is removed by filtration. Color can be judged visually using standards (a platinum/cobalt standard where 1 mg/l KPtCl6/CoCl2·6H2O = 1 Pt-Co Color Unit, with platinum as chloroplatinate ion.) A Hach 2010 spectrophotometer (using light at 455nm and measuring transmission through 2.5 cm of water) was used to determine true and apparent water color.

Figure 9. The color scale is 0-500 units. Both samples were relatively low in color but yellowness was apparent to the eye in the aquarium water.

Water samples were gathered from an aquarium and compared to freshly mixed artificial sea water. The artificial seawater (ASW) was mixed with a submersible pump for 24 hours. The pump was removed and the mix was then allowed to settle for several days. The aquarium had gone a few months without a water change and used a refugium filled with Chaetomorpha alga and a downdraft protein skimmer for filtration. Small amounts of an unidentified brown alga grew in the aquarium and provided a natural food for a single Yellow Tang (Zebrasoma flavescens). The aquarium sample could be considered as being towards ‘worst case’ and the artificial sea water sample ‘best case.’ These samples were taken to the lab and analyzed for ‘apparent color’ (samples were not filtered) and ‘true color’ (after the sample was filtered through a 0.45 micron filter.)

Visually, the aquarium sample had a yellow tint to it while the ‘fresh’ ASW sample appeared clear. Figure 9 shows the results.

The color of water invariably increases with higher pH values and Standard Methods states pH should be reported along with the color value. So, the aquarium sample pH was 8.18, and the ASW sample was 8.02.

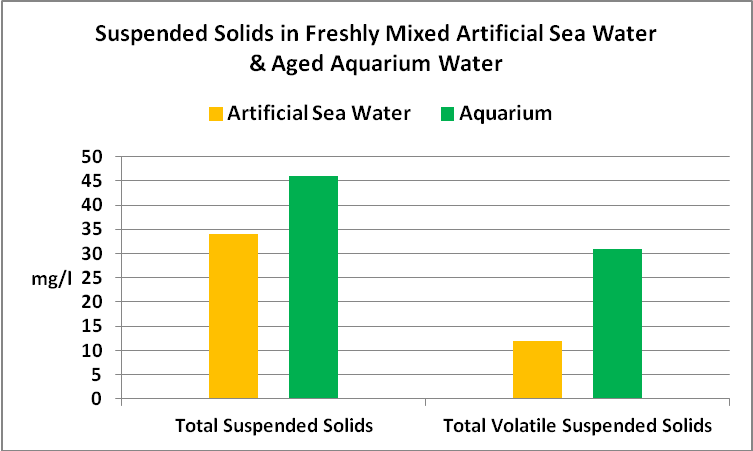

Determination of Suspended Solids

Suspended solids play a critical part in water clarity, since they can absorb light, or scatter it and prevent downward transmission.

The protocol for determining total suspended solids and volatile suspended solids was as follows. Known volumes of the samples were filter through pre-combusted and pre-weighed glass fiber filters with a pore size of 1.5 microns. These were dried at 103C for one hour. Filters were weighed once again and values were plugged into this formula:

a-b / sample volume (ml)*1,000

where: a = filter + retained solids weight (mg), and b = filter weight (mg)

Volatile solids were determined in this manner: The filters were placed in a muffle furnace with at a temperature of 550C for 20 minutes. After cooling for a few minutes in a desiccator, the filter was weighed, and this formula used.

a-c / sample volume (ml)*1,000

where: a = filter + retained solids weight (mg), and c = filter + filter retained solids weight after combustion (mg)

See Figure 10 for the results.

0 Comments