By Ret Talbot

The Endangered Species Act (ESA) is the Nation’s most effective conservation legislation. Despite its effectiveness, the ESA has always been controversial, especially when the conservation of a species may be at odds with commercial activity. From the first ESA listing of a small freshwater fish in Tennessee, critics have portrayed the ESA as “environmental overkill” and “extremism.” As one early headline put it, the ESA is “absurdity for environmentalism.”

This hatchling has already made it farther in life than a lot of his siblings and peers. He has already overcome much and now he looks ahead to his future challenges under the waves. Photo by Wikimedia Commons.

In the last few months, an increasing number of aquarists have become vocal critics of the ESA, as a number of aquarium animals have been listed or considered for listing. Some of that criticism has been based on a lack of factual information about the ESA, how species are listed and what the outcome of a listing might be. Despite what various advocacy and media outlets have stated, an ESA listing of an aquarium animal is not the de facto end of that fish, coral or other invertebrate in the aquarium trade or hobby. A listing does not necessarily mean it will become illegal to keep that animal or breed that animal in captivity.

While the prohibition of commercial activity associated with a listed species is a possible outcome of an ESA listing, there are other outcomes that balance protecting an imperiled species and commercial interest, without interfering with the conservation of the species. This is particularly the case with animals listed as “threatened” under the jurisdiction of National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), which oversees all currently listed aquarium species. The process by which the ESA is implemented is a public, transparent process. It’s critically important that all stakeholders understand this and engage when and where appropriate based on factual information and the best available science. Of course most important of all is acting in the best interest of any imperiled animal, especially as climate change continues to threaten more and more species. This is true even if that means no longer being able to keep it in an aquarium.

What is the ESA?

In 1973, President Nixon signed the ESA into law with broad bipartisan support. In the face of legal challenges, the ESA has been defended by the U.S. Supreme Court as “the most comprehensive legislation for the preservation of endangered species ever enacted by any nation.” Over the last four decades, more than 2000 species have been listed as either “endangered” or “threatened.” It’s estimated that more than 200 species would have gone extinct without ESA protection, and only two species have gone extinct after listing (eight other listed species went extinct during review for listing). While the average recovery plan for a listed species is 42 years, the typical duration of a listing at present is about half that. Of all currently listed species, 90% are recovering at a rate consistent with federal recovery plans.

Richard Nixon signing into law the Endangered Species Act, Dec. 28, 1973. Photo by Wikimedia Commons.

The ESA is often said to be an “all or nothing” law. Either a species is listed and receives protection or it does not. If an animal is listed, it can be listed as either “endangered” or “threatened.” An “endangered” listing means that the species in question is “considered in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range.” A “threatened” listing means “a species is considered likely to become endangered within the foreseeable future, but is not currently in danger of extinction.” Because the Act is called the Endangered Species Act, it is not infrequent to hear people call a species “endangered” when it is officially listed as “threatened.” The distinction is crucial because of the different ways the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) NMFS implement the ESA.

A Complex Piece of Legislation Going Far Beyond Prohibitions

While much of the media attention focuses on the prohibitions resulting from an ESA listing, the Act itself is a complex piece of legislation with many components designed to benefit a listed species. The ESA, which has been amended by Congress several times since 1973, is divided into 11 sections. Each section addresses a different aspect of the law. For example, Section 4 concerns the listings process, critical habitat designation and recovery plans for listed species. Section 6 mandates cooperation with states. Section 7 requires interagency consultation on any federal project that might affect a listed species. Section 10 outlines permits, and Section 11 covers penalties and enforcement, as well as providing a mechanism for citizens to litigate against the government.

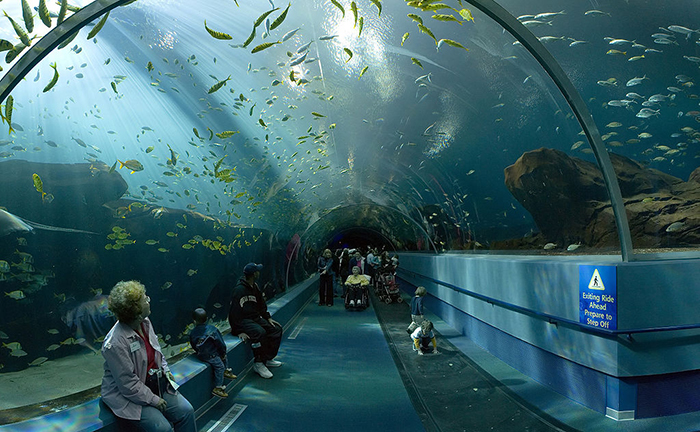

The Ocean Voyager tunnel at the Georgia Aquarium. Photo by Wikimedia Commons.

ESA prohibitions are addressed in Section 9. This section often receives a disproportionate amount of the press time because prohibitions can put an end to commercial activity and other activities related to a listed species. In the language of the ESA, Section 9 prohibits “take,” which is defined as “to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or attempt to engage in any such conduct.” In addition to direct “take,” Section 9 has been used to address damage to habitat and land-use activities, which may affect essential activities for a listed species. Essential activities might include breeding, migration and feeding.

The ESA gives authority to implement the Act to “the Secretary,” which means either the Secretary of the Interior, who oversees USFWS, or the Secretary of Commerce, who oversees NMFS. Most listed species fall under the jurisdiction of USFWS, with NMFS having jurisdiction over a much smaller number of marine and anadromous species. While both Services are charged with implementing the same piece of legislation, the way they implement the law is different. Common misperceptions amongst marine aquarists about recent ESA listings of aquarium animals often stem from a lack of understanding about how the two services implement the Act. Most notably, USFWS automatically extends so-called Section 9 “take” prohibitions assigned to species listed as “endangered” to those listed as “threatened.” NMFS does not presumptively extend those prohibitions and instead uses, when it deems necessary and advisable for the conservation of the species, a separate rulemaking process to extend prohibitions to “threatened” species.

How a Species Gets Listed

The path to listing is a long one with many built-in checks and balances. There are two primary ways a species is considered for listing under the ESA. Either federal scientists with USFWS or NMFS undertake a status review of a species on their own, or citizens can petition a species for listing. The latter path to listing is more controversial, but it’s the way that most species have been listed after Congress amended the ESA in the early 1980s. At the time, Congress was worried species were not being listed as expediently as expected, and so they instituted timelines for the listing process and gave citizens the power under Section 11 to petition and, if necessary, litigate against the government.

In the case of a petition, USFWS or NMFS is required to issue a 90-day finding for each petitioned species. The 90-day finding is a decision regarding whether the petitioned action may be warranted. In making a 90-day finding, the government puts the onus on the petitioner by relying heavily on the information in the petition itself to determine whether a status review is warranted. As such, the petition must include credible, citable data supporting a listing based on the best available science. In the event of a positive 90-day finding, government scientists begin a 12-month status review. The status review is a comprehensive review of the species, the peer-reviewed scientific literature concerning the species and the threats identified as posing an extinction risk to the species. The status review is peer reviewed and then summed up in a peer-reviewed 12-month finding that, in the case of NMFS, either proposes the species for listing or concludes listing is not warranted.

Marine conservation groups help manage and protect sea turtle populations. Photo by Wikimedia Commons.

If a species is determined not to be warranted for listing, citizens have the opportunity to challenge that decision. If, on the other hand, a rule is proposed to list a species, there is the opportunity for public comment either supporting or challenging the listing. Within a year of a proposed rule, the government is required to withdraw the rule, publish a final rule, or invoke a 6-month extension when there is substantial disagreement among experts. A final rule may be identical to the proposed rule, or it may be an amended rule. A final rule generally becomes law 30 or 60 days after it is published. NMFS has waited up to 90 days in cases where people affected by the rule may need more time to complete permit applications before the rule is effective. Again, there is the opportunity to challenge a final rule if the rule is thought to be unlawful.

Environmental Groups, Businesses and Lobbyists

The engagement in ESA issues by environmental groups, businesses and lobbyists often creates controversy. It’s important to remember, however, that Congress intentionally empowered citizens to engage in the ESA process because, in their opinion, not enough animals were being listed quickly enough. Because most citizens don’t have the resources to petition or litigate against the government, environmental groups like the Center for Biological Diversity, WildEarth Guardians, the Sierra Club, Defenders of Wildlife, and others have taken on that role. In part this is because preparing a credible petition takes resources and expertise beyond that of most private citizens, and most of these environmental groups have staff scientists who work on these issues.

In addition, environmental groups working on ESA issues also often have staff lawyers for much the same reason that they have staff scientists. Litigating against the government for missed deadlines or situations in which there is concern the government is not implementing the ESA legally is a task that is generally beyond the resources of most private citizens.

Of course environmental groups with a pro-listing bias are not the only entities that may take advantage of the opportunity to litigate against the government in ESA cases. While private citizens are also given the power to litigate ESA listings they believe are unlawful, such suits are generally too complex and expensive for individuals to undertake. In the same way that environmental groups act on behalf of citizens when it comes to litigating ESA cases, businesses and business groups, as well as lobbyists, also sometimes take the government to court. Like the environmental groups, large businesses and lobbying groups often either have their own scientists and lawyers or contract with scientists and lawyers.

A member of the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries dressed in a whooping crane costume, opening a section of fence to let the birds into an open pen. Photo by Wikimedia Commons.

4(d) Rulemaking

If a species under NMFS jurisdiction is listed as “threatened,” the Section 9 take prohibitions discussed earlier are not automatically applied. NMFS makes a determination after listing regarding whether or not prohibitions on take are necessary. If NMFS determines that take prohibitions are necessary, then it will apply those prohibitions through a rulemaking process outlined in Section 4 of the ESA. The resulting rules, commonly referred to as 4(d) rules, may extend to a “threatened” species some or all of the take prohibitions applied to an “endangered” species. In addition, 4(d) rules may provide exemptions to the take prohibitions that allow some take so long as it does not interfere with the conservation of the species.

The 4(d) rulemaking process is a transparent process with the opportunity for stakeholder input in the form of public comment and direct communication with NMFS personnel. Understanding and engaging in the 4(d) rulemaking process is one of the most effective ways a private citizen can be constructively involved in a listing. While it may not make sense for an individual to submit his or her own public comment if that person doesn’t have expertise with the species or a working knowledge of commercial activity related to the species, an individual can play a vital role in supporting and shaping the actions of a group that can effectively act on his or her behalf. Environmental groups and lobbying groups both depend on the support of individuals in addition to their other revenue streams.

The ESA and Climate Change

The ESA remains the Nation’s most effective conservation legislation, and so it will continue to be employed with vigor to protect species from myriad threats. With global climate change posing some of the gravest threats to species, it should come as no surprise that the ESA is being used to combat a warming climate. While there are those who remain stalwart in the belief that the ESA was not designed to address issues of climate change, that debate really only continues to the detriment of those engaged in it. The reality is that climate change is—and will increasingly be—an important consideration when making ESA decisions. The reality is that the courts are largely defending listing decisions based on climate change and both USFWS and NMFS are employing novel approaches to conservation based on a changing climate.

The ESA has always been controversial, and given the polemic surrounding climate, the fact the ESA is increasingly used to address climate change will only make the Act more contentious. Emotions run high and deep, but when stepping into this debate, we must make sure we are doing so based on a factual understanding of the ESA and the way it is implemented. We must make sure our claims are based on the best available science at the time of consideration and not political leanings, anecdote and hyperbolic rhetoric. We must insure the things we say are based on data and that we are always acting in the best interest of the species regardless of how that may affect us personally or professionally.

Admittedly that is an awfully tall order to fill. When an ESA decision threatens one’s hobby or, more pointedly, his or her professional life, it’s hard to be objective. The listing of aquarium animals under the ESA could radically change the aquarium trade and hobby. It’s not beyond the realm of possibility that it could essentially mean the end of keeping many species of corals and fishes in an aquarium. But there are also other possible outcomes.

As more species are listed with climate change cited as the primary threat, increasingly the ESA is going to butt up against commercial interest. This is particularly the case with marine species. While reef aquarists may be up in arms about the listing of what most of the population would consider to be some obscure corals with little commercial value, imagine the response when species for which there are major food fisheries are listed.

I live in Maine, and I have a hard time imagining how the lobster fishery and industry would respond to an ESA listing of the American lobster. I bring this up in closing because I believe NMFS sees where this is headed, and I believe they realize that they are going to need to innovate in the best interests of listed species and the ESA itself. In short, they are going to need to find ways to allow for commercial activity that doesn’t jeopardize the conservation status of listed species. They are going to need to work closely with all stakeholders, as they are already doing in several cases, to not unnecessarily disrupt commercial activities and still bring the full force of the ESA to bear in protecting imperiled species. Rather than simply criticizing the ESA because of what aquarists are afraid it will do, I believe aquarists have an opportunity here to help shape the future of the ESA, which remains the Nation’s most effective conservation legislation.

0 Comments