By Nathalie Winans

Tech-heavy reef systems are all the rage these days. Tanks everywhere are loaded with hardware and software—lighting that replicates tropical weather patterns, automatic feeders and top-offs, media reactors, controllers and apps that give you remote access to everything in your reef.

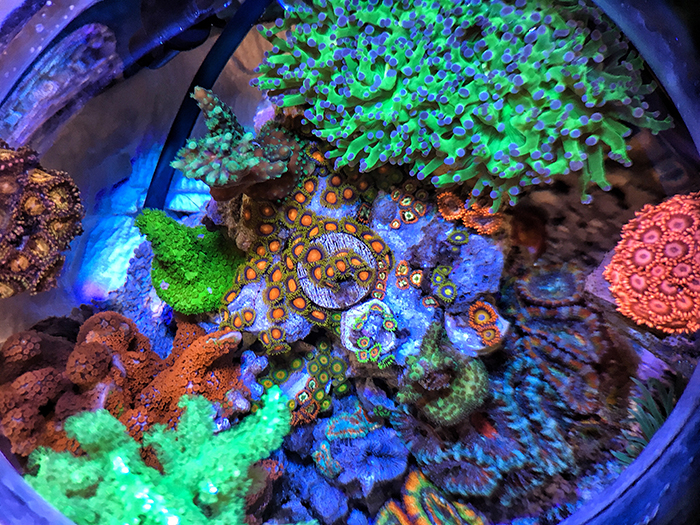

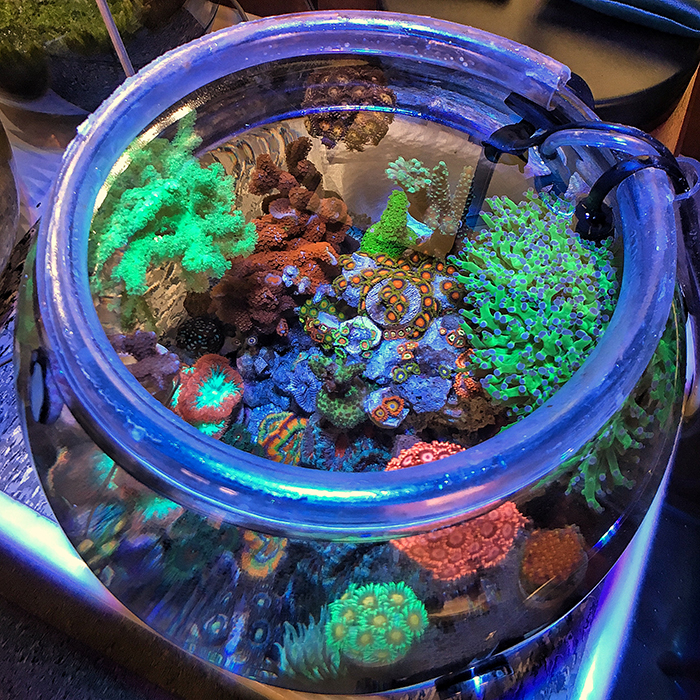

Photo by Nathalie Winans.

A lot of that technology is ingenious and useful, and in many situations it makes great sense. But it’s not the only way to keep a thriving reef tank.

Burned-Out Reefer

I used to keep relatively complex reef systems. I kept seahorses and a mandarin for several years. I was accustomed to providing feedings two or three times daily for these beautiful, high-maintenance animals. I used oversized skimmers and heavy filtration as well as frequent large water changes to accommodate large bioloads. When taking business trips and vacations, I had to factor in the significant cost of bringing in an aquarium maintenance company twice a day to feed the fish and do regular upkeep. I dealt with various equipment failures as well as invasions of flatworms, zoanthid- and montipora-eating nudibranchs, hydroids, vermetid snails, and many kinds of nuisance algae.

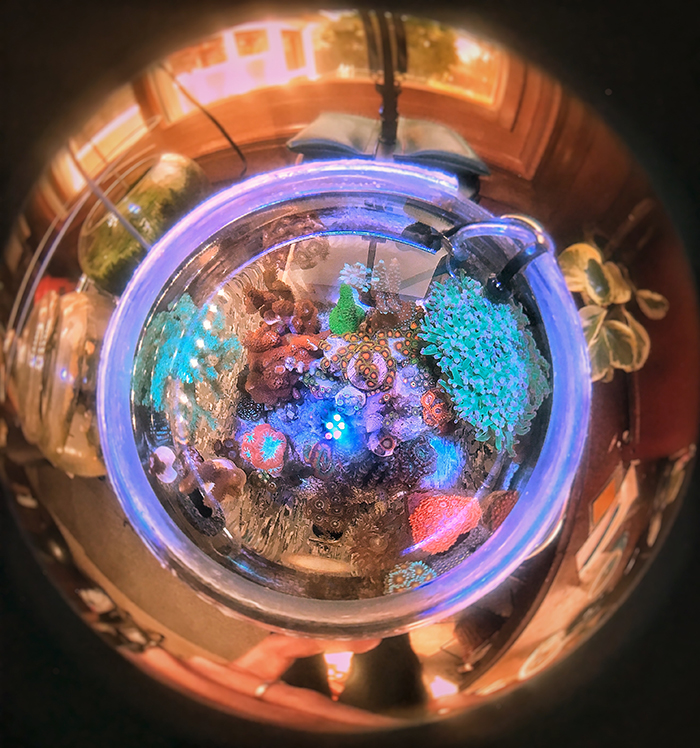

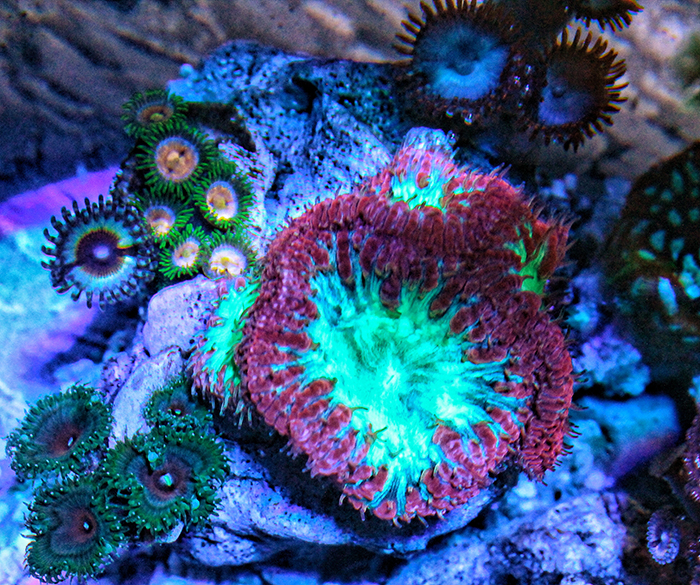

Photo by Nathalie Winans.

After six years of this kind of reefing, I was totally burned out. I wanted to paint more, work out more, go out more, and save more money. I found that I spent more time working on my tanks than enjoying them; in short, the hobby had lost its magic for me. So in early 2016, I took my tanks down and sold everything.

I didn’t want to get out entirely. I researched and set up a one-gallon bowl for opae’ula shrimp (halocaridina rubra)—brackish shrimp from Hawaii that require no circulation, filtration, heaters, water changes, or even feeding as long as they receive enough light to grow the biofilms they feed on. That system is still going strong, but I wanted just a little more.

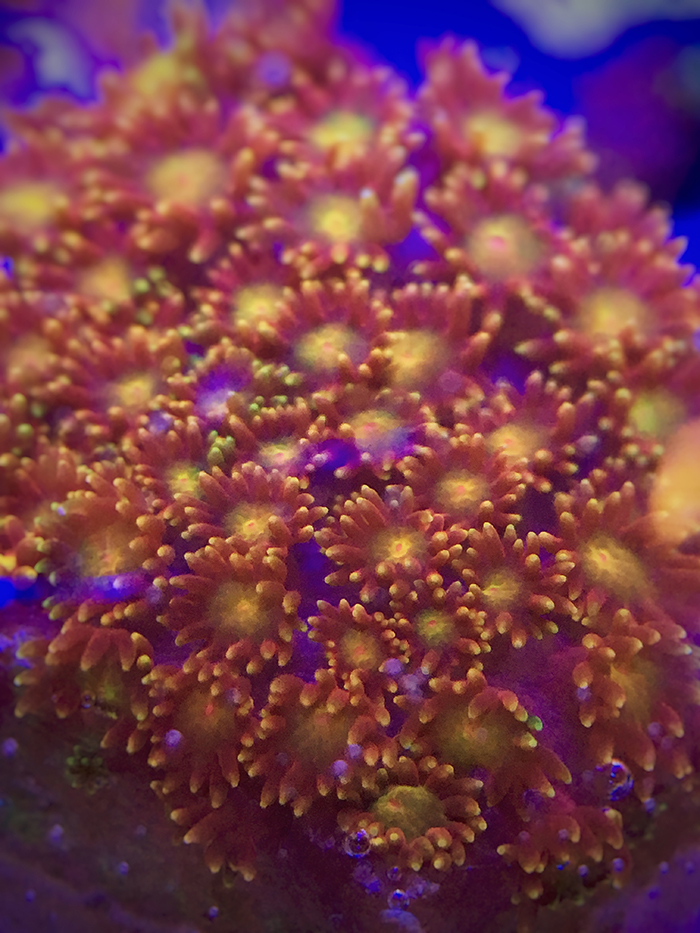

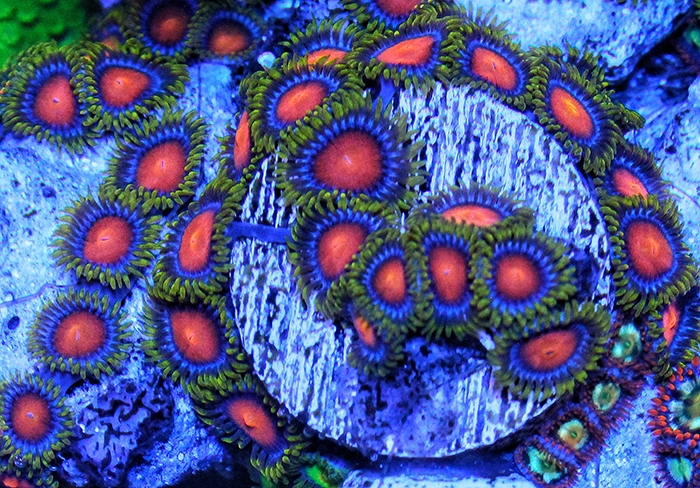

Photo by Nathalie Winans.

As I assembled my opae’ula bowl, I thought about pico reefs of similar size, like the vase reef that Brandon Mason has maintained for over ten years. While reading about Brandon’s reef, I came across Mary Arroyo’s magnificent Maritza the Vase Reef, another low-maintenance pico that has been running for several years. I had seen pico reefs at local fish stores, but they tended to be pretty unimpressive, rarely contained anything more demanding than mushrooms and other soft corals, and didn’t seem to last very long. Brandon and Mary’s systems showed the true potential of these tiny reefs. It didn’t take long for me to realize that a reefbowl could work for me.

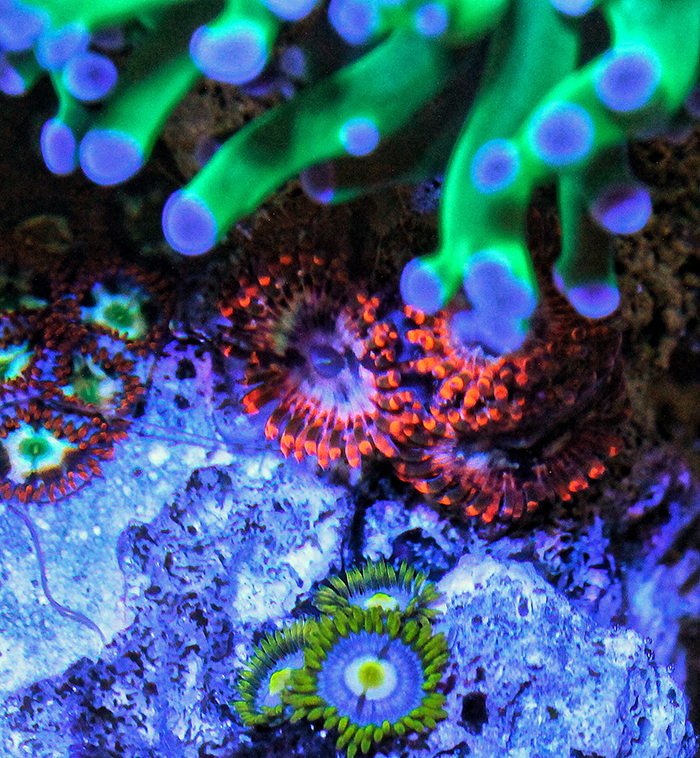

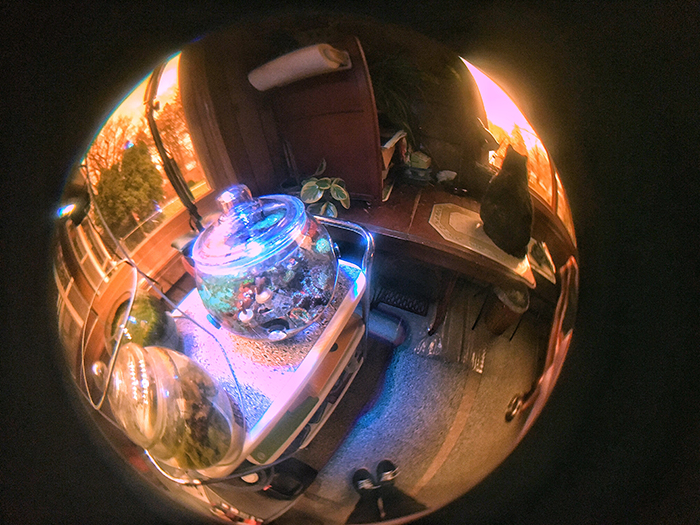

Photo by Nathalie Winans.

Thirteen months in, my reefbowl is not just doing well; it’s doing better than any other reef tank I’ve had. This isn’t luck. It’s a combination of generous feeding and complete weekly system renewal through large water changes and aggressive detritus removal, done with the most simple, inexpensive equipment.

A Different Operating Model

There are lots of effective models for home reefkeeping. The one that is right for you depends on your resources, your space, your time, and your goals. A big, complex reef tank can be a breathtaking thing. It’s great if you love tinkering with the build. Sumps, skimmers, dosers, reactors, controllers, and automatic top-offs are a common sight in these systems.

But that model wasn’t working for me. I found it tedious, frustrating, and very expensive. I wasn’t really interested in maintaining and troubleshooting complex mechanical systems. I just wanted to grow coral in the simplest way possible.

Photo by Nathalie Winans.

Like a bigger reef tank, my 1.75-gallon reefbowl provides the light, flow, nutrient delivery, and nutrient export that make corals grow. But in every other sense, it’s a totally different operating model. It meets these essential coral needs with minimal, inexpensive equipment and a single form of comprehensive nutrient export.

An inexpensive par38 lamp, in a conventional light fixture, provides enough PAR to grow stony corals. An analog time switch keeps the light on an eight-hour cycle. Warmth is provided by a tiny heater designed for betta tanks. Because the heater has no thermostat, a digital temperature controller is used to prevent overheating.

An air pump rated for 10-20 gallons provides strong random flow and gas exchange while taking up almost no space in the bowl. (And because the air pump is outside the tank, it requires far less maintenance than a submersible circulation pump.) No airstone is needed or desirable; the resulting microbubbles would disrupt visibility and irritate corals.

Photo by Nathalie Winans.

A repurposed glass terrarium lid keeps evaporation to a minimum. The lid has a built-in lip on the inside that allows condensate to drip back into the water. To prevent salt creep, I sliced some clear PVC tubing along its length and inserted it on the circumference of the bowl opening, leaving a 3-cm gap in the back that provides for entry of the airline, heater, and temperature probe as well as the egress of air from the pump.

Maintenance

Along with the corals themselves, live rock and a thin layer of aragonite flakes are the only form of filtration in my reefbowl. Unlike most coral reef aquariums, the reefbowl functions without any form of dosing, skimmers, ATO, or mechanical or chemical filtration.

Photo by Nathalie Winans.

Once a week, I treat my corals to a generous quantity and variety of coral feeds at various particle sizes, including Rod’s Food Coral Blend, Reef Roids, Reef Nutrition Phyto Feast, and Fauna Marin Ultra Ricordea & Zoanthus with Ultra Min D. I let the corals eat for several hours while I heat their new saltwater. Then I begin the water change. My tools are a turkey baster, siphon hose, bucket, towels, a long forceps, half of a cotton swab, and a tiny amount of 35% hydrogen peroxide.

I use the turkey baster to blow detritus out of the rocks and sand and keep it in suspension for removal. This is a critically important step for removing organics. Then I siphon out almost all the water.

Photo by Nathalie Winans.

With all corals and rocks exposed to air, I have full access to facilitate pest elimination. I dip the cotton swab in hydrogen peroxide, pick it up with the forceps, and touch it to any nuisance algae that has appeared in the past week. At 35% concentration, hydrogen peroxide must be used with caution, but it is very effective in killing nuisance algae. Most algivores would starve in such a tiny bowl, so I fill the niche of algae predator in this little ecosystem.

Although I carefully inspect every frag for pests, my corals have come in with aiptasia anemones, hydroids, and vermetid snails at one time or another. A drop of superglue entombs them in seconds, with no chance of further propagation.

Photo by Nathalie Winans.

This work complete, I fill half of the reefbowl with new heated saltwater to rinse away any traces of peroxide and stir up additional detritus. Then I re-drain it, fill it to the top with new saltwater, clean the glass lid, and turn on the heater and air pump. The corals return to their former glory within a couple of hours. The whole process takes, at most, half an hour a week.

Apart from the weekly water change, I almost never remove the lid. About halfway through the week, I add a few ounces of RODI water to compensate for what little evaporation has occurred.

Photo by Nathalie Winans.

That’s about it. Contrary to my earlier experiences in the hobby, I spend a lot more time admiring the reefbowl than I do maintaining or troubleshooting it.

Results

Based on what I was told when I entered the hobby seven years ago, my reefbowl should not thrive. I was told that bigger is better, that larger water volumes are the best way to provide corals with the stable parameters they need to grow. With such a tiny volume of water, no mechanical filtration, and no dosing for calcium or alkalinity—with nothing more than 100% water changes and diligent detritus removal once a week—the parameters should swing wildly, causing all but the most resilient corals to bleach, necrotize, or otherwise fail to thrive.

Photo by Nathalie Winans.

But that has not been my experience, nor has it been for those whose vase, bowl, and jar reef systems I emulated. From acropora to zoanthus, these systems grow coral.

Most of the corals grow slowly (not a bad thing in such a small space). But they grow. I don’t see tissue necrosis or bleaching. What I see are beautiful colors, excellent polyp extension, and slow, steady growth.

There have been exceptions. A stylophora withdrew its polyps and necrotized within a week of introduction. A frag of zoanthids slowly wasted away to nothing.

Photo by Nathalie Winans.

But for every coral that has failed to thrive, many more are growing beautifully, including SPS and LPS as well as soft corals. There are three varieties of acropora, two of Montipora digitata, three of acanthastrea, three gonioporas, many different zoanthids and palythoas. The digitatas, in particular, are growing a little too well. I’ve fragged them several times, and they are still invading the space of other corals.

An extremely small mixed reef presents other challenges. Early on, I nearly bombed the reefbowl to oblivion with an overzealous peroxide treatment. (All the corals recovered except for a xenia frag.) I traded in a beautiful chalice after it consumed most of my favorite acanthastrea. It’s hard to dial in the light levels to benefit all corals; I raised the lamp from 16” above the water line to 17.5” because I felt the zoanthids were getting too much light, and now one of the acroporas is less colorful than before. A euphyllia is getting too close to its neighbors; I’ll soon have to remove it or put up a barrier.

Photo by Nathalie Winans.

An unfiltered system of this size is not an appropriate habitat for fish, or even for most invertebrates. It is, above all, a coral garden. Two trochus snails and a smooth-shelled turbo snail act as clean-up crew. In the last few weeks, I’ve added a small pom pom crab and a tiny blue leg hermit crab.

Reflections

Given how easy and fun my reefbowl has been, I can’t help but believe this model of reefkeeping could bring a lot of people into the hobby who might be intimidated by big, expensive, complicated systems. (For that matter, I could easily imagine a lot of longtime reefers trading their high-maintenance tanks for a reefbowl.) They are ideal for small spaces and small budgets. As long as you account for their obvious limitations (please don’t put a clownfish in a bowl!) and are diligent about water changes and detritus removal, these tiny tanks are an absolute joy to keep.

Photo by Nathalie Winans.

Reefbowl Specifications

Display: 1.75-gallon (7.5″ high by 9″ diameter) glass sphere

Lighting: ABI 12W Tuna Blue par38 LED

Heater: Bettastik 7.5 watts

Circulation: TOM Stellar Air Pump rated for 10-20 gallons; bare airline (no airstone)

Skimmer: None

Filtration: None

Filter media: None

Dosing: None

Top Off: Manual top-off with RODI water, 1-2 times a week

Evaporation control: Repurposed glass terrarium lid; vinyl tubing added around rim to control salt creep

Controller: Finnex HC-810M digital temperature controller; analog time switch for light

Substrate: Aragonite flakes

Rocks: Dry Marco Rock

Fixture: Black architect table lamp from Amazon.com

Light cycle: 11am-7pm with time switch; intermittent sunlight from east & south windows and LED light from shrimpbowl

Age: Established March 5, 2016

0 Comments