By Richard Aspinall

Back in the increasingly distant and hazy past, when everything was in black and white, a young and slightly plump teenager in the North of England asked why he should study Latin.

“But, no one speaks it,” he said. “It’s a dead language.”

“Precision is why…you’re studying science aren’t you? Isn’t that about precision?” replied the long-suffering teacher, who had this oft-used speech prepared for just this eventuality.

“Latin is the language of science,” he said and I was sent back to my seat pondering his words.

For some reason my school had decided that those of us who showed a talent for languages should spend three years exploring this complex and to me baffling language. We were offered occasional if somewhat tenuous explanations why we should wrestle with a language in which word endings were more important than word order. Apparently our reward was that this esoteric knowledge would be useful in later life in some way that was hinted at but never qualified

Pseudocheilinus ocellatus – the genus name shows the relationship to the Cheilinus genus (a genus that contains many larger wrasses such as the Maori wrasses and the massive Humphead wrasse) all of which have large lips, and the specific name refers to the ocellus – the prominent ‘eye spot’ on the caudal peduncle.

To be honest, I didn’t do that well, I passed my exam, but thought pretty much that I’d had my time wasted by a curriculum that looked to the past and not the future. Over time though, I have come to change my view.

Another Pseudocheilinus species, the sixline wrasse, hex means ‘six’ (derived from Greek) and taenia means ‘striped.’

Ctenochaetus tominiensis – identified from the Tomini islands, similarly C. hawaiiensis is named for the location of its identification. Such geographical names don’t always indicate a species’ range, but are a good clue to it. Note that the t in tominiensis and h in hawaiiensis are not capitalized.

Pterapogon kauderni – a lot has been written about the Banggai recently and there is no better description of the process of identification and naming of this iconic fish (named in honor of Walter Kaudern), than that found in the Banggai Rescue Project’s book by Ret Talbot, Matt Pedersen, and Matthew Wittenrich.

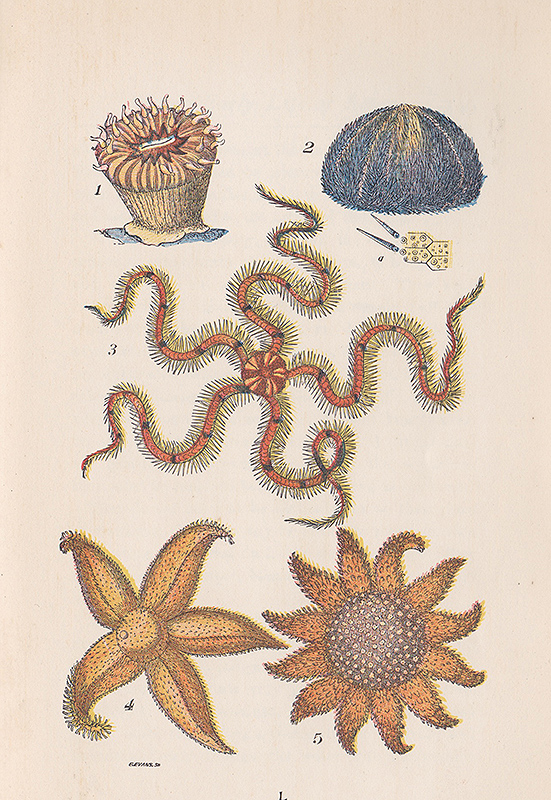

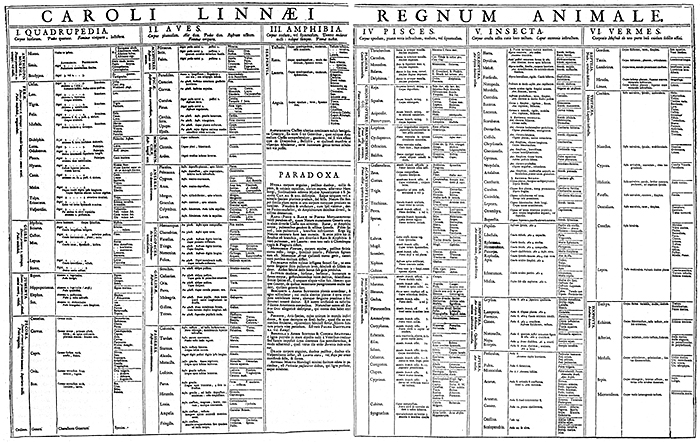

Classification (taxonomy) is based on observation and collection of specimens. There is a certain amount of truth to the concept of the Victorian vicar collecting specimens between writing sermons and contributing to the store of knowledge. Reproduced from Common Objects from the Sea Shore, Rev. J. G. Wood, 1894.

The History of Classification

Humans have always tried to define groupings within the natural world. It is in our nature to seek out similarities (and differences) to help us understand the world around us. Our modern understanding of classification – the science of taxonomy – uses techniques that would have been beyond the scope of imagination of those pioneers, who laid the science’s foundations, but it is to them that we owe a great debt.

Latin (and Greek) have been used as the language of science for centuries. Scholars from across Europe were able to exchange ideas in a common tongue and it was in this background of Latin (and Latinate nomenclature) as the lingua universalis, that the framework of the scientific classification of life was based.

Several writers and thinkers from the ancient past had sought to classify life into useful groupings; the greatest of these was Aristotle. Aristotle’s contribution to zoology is somewhat overshadowed by his other contributions to the fields of philosophy, music, politics and logic, but it is worth noting he spent a great deal of time exploring the natural world, largely within a lagoon on the Greek island of Lesvos. A lagoon I once visited, that is indeed replete with life in its shallow, warm waters.

Aristotle believed that creatures were arranged along a ‘scale’ which saw an ever increasing perfection from primitive, simple forms like plants through animals to humanity. The Great Chain of Being – the Scala naturae – had eleven subdivisions based on various characteristics including the degree of complexity at birth and the qualities of the soul. Some of the philosophical concepts of an ever increasing and above all ever improving gradation towards perfection have placed humans atop the highest branch of a theoretical tree that hasn’t always been of benefit, but more of that later.

Several writers such as Aristotle’s student Theophrastus built on this work, but it wasn’t until 1735 that the scientific world saw a workable classification system, one that we still use today.

Linnaeus was extremely fond of naming plants after people. He named the genus Magnolia after the French Huguenot botanist Pierre Magnol, whom he greatly respected, while the genus Sigesbeckia, a small creeping herb that grows in mud was named for Linnaeus’ main critic, Johann Siegesbeck, with whom Linnaeus quarreled.

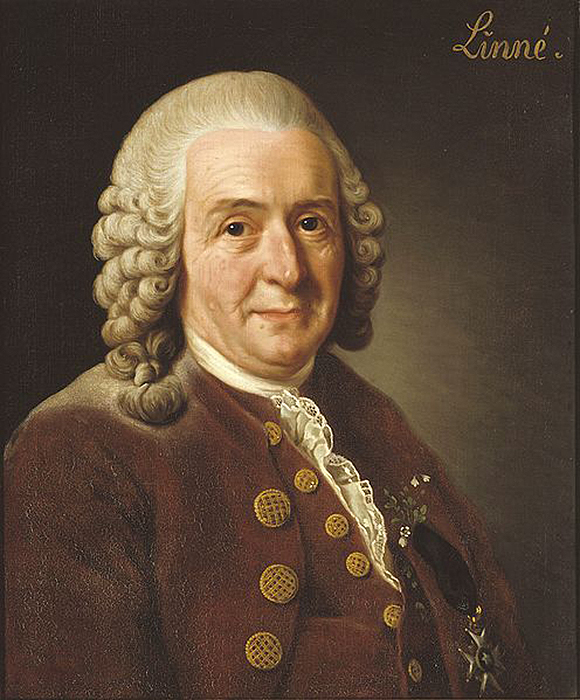

Carl von Linné was born in the Swedish village of Rashult. In his early life he showed a passion for botany and following his ennoblement he adopted the Latinate name of Carolus Linnaeus. Linnaeus revised and built upon the earlier work of Johann and Gaspard Bauhin who were the first to define certain terms and groupings that Linnaeus would incorporate into his great work Systema Naturae.

Systema Naturae, which was frequently revised and developed, was first published in 1735. The full title of the 10th edition, which was the most important one, was:

Systema Naturae, which was frequently revised and developed, was first published in 1735. The full title of the 10th edition, which was the most important one, was:

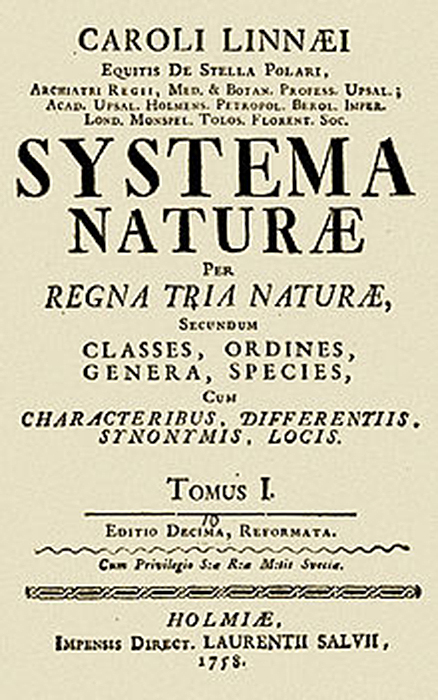

Systema naturae per regna tria natuae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis.

This translates as: System of nature through the three kingdoms of nature, according to classes, orders, genera and species, with characters, differences, synonyms, places.

This sentence is the formation, the very root of the modern science of taxonomy (deriving from the Greek ‘Taxis’ meaning order and ‘nomos’ meaning law), and is recognizable today to anyone who has looked at a scientific description of a species.

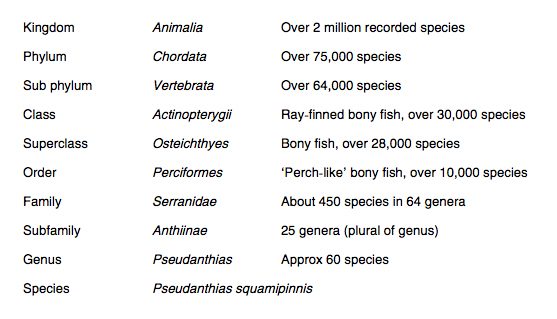

Linnaeus was the first to use two names to identify a species (rather than complicated longer, polynomial names), and indeed many species named by him retain the letter L appended to their binominal to indicate this, but there are several levels, or ranks above this, and as we descend through the rankings the number of species lessens until we reach the ‘target’ organism. The best way is to start with an example. Let’s take the Lyretail Anthias (Pseudanthias squamipinnis) as a starting point.

This is a relatively simple taxonomic structure, there are several ‘extra’ subdivisions that can be inserted at various levels such as infraorder, clade, subclade, and tribe and then below the species level we might have: form, subspecies or variety – all are added to create groupings to show similarities and relationships. Sometimes these are not needed in fish groups that show simple relationships but in groups that have exhibited rapid evolution, recent geographical isolation or show many shared characteristics – Rift Valley Cichlids are a great example – these subdivisions are very useful.

This is a relatively simple taxonomic structure, there are several ‘extra’ subdivisions that can be inserted at various levels such as infraorder, clade, subclade, and tribe and then below the species level we might have: form, subspecies or variety – all are added to create groupings to show similarities and relationships. Sometimes these are not needed in fish groups that show simple relationships but in groups that have exhibited rapid evolution, recent geographical isolation or show many shared characteristics – Rift Valley Cichlids are a great example – these subdivisions are very useful.

The taxonomy of many African Cichlid groups has presented challenges to science, so much so that the term ‘species flock’ has been used to describe some populations in recognition of their currently ongoing adaptive radiation.

Another, perhaps more relevant example might be the genus Amphiprion, where groupings of closely related species have been created to include species with very similar traits and placed in a grouping known as a Complex. The Amphiprionids have undergone some revision of late, with new species added, and it can be quite baffling to those of us who simply ‘dip in and out of’ the taxonomic world. Fishbase lists 69 species in the Amphiprion genus and that will suffice for me. Confusion is occasionally found in the trade as well and some rare species have been unintentionally incorrectly listed by dealers and DNA evidence used to settle arising issues.

The Lyretail’s binominal gives us several clues about its taxonomic status and morphology. Squamipinnis means ‘scale finned’ and its genus name translates as ‘fake fish’ in Greek. The original anthias specimen was named by Linnaeus; Anthias anthias is found in cooler sub-tropical waters of the Mediterranean and the Atlantic African coast and became that which gave its name to other genera and species as they show deviation from this norm or ‘type’…

What these stores show up though is that names are simply that, they are just groupings of similarity that scientists have assigned based upon their research, which can be thought of as the best information available at the time –as time passes and the canon of data builds, things may change.

For many decades the study of taxonomy, was limited to studies of morphology – that is the structures, shapes and biological characteristics of species led scientists and researchers to place species within one group or another – teeth, fin rays etc… Species were regularly(and still are) switched from genus to genus and indeed some times more radical changes are proposed and accepted by the scientific community – often meaning many of our text books are out of date and quite often many of the web-based resources we rely upon.

On occasion new structures are proposed for groups and some ‘messy’ classifications are ‘tidied’ to make them more rational and more easily followed or are revisited because of new knowledge and newly identified species – nothing changes in (real) biology of course, these structures are for our benefit and are designed to show relationships and commonalities. We are attempting to put species and species groupings into defined boxes which does not entirely reflect reality and forces us to ask the question what is a species? How do we define such a thing? What is the minimum difference that defines one creature as from one species and another, perhaps similar creature, from another?

What about the Regal Tang, We know it as Paracanthurus hepatus, but what of the White Bellied Regal Tang from the Western Indian Ocean. Should it be a different species? Well, no, the differences aren’t considered sufficient to warrant deeming it so and it is often described as Paracanthurus hepatus var., a variety of the main species, but we must accept species ‘boundaries’ as movable. Geographic isolation is a significant causative agent in separating two distinct populations of one species and allowing them, over time, to form distinct new species, which ichthyologists will determine as such.

Zebrasoma desjardinii (from the eastern Pacific) is clearly closely related to Z. Veliferum from the Western Indian Ocean and Pacific, but they are separated by geography and two distinct species have formed as the populations have diverged through natural selection.

Several excellent examples exist of geography creating and fostering new species and are evidenced by the high degree of unique or ‘endemic’ species found within limited ranges around island groups or smaller seas separated somehow from the wider ocean, Clarion Angels and Orchid Dottybacks are just two species that come to mind.

The term ‘species’ then is not a hard and fast ruling, it is obviously mutable over time, but more so, it is a term we have invented to create order in a changing and changeable world. It is remarkable just how hard it is to define ‘species’ in a simple way that cannot be unpicked or animals suggested that fall outside of its scope, we must accept it as a ‘work around’, something that we use as a working model, a concept, rather than something that can ever be entirely satisfactory.

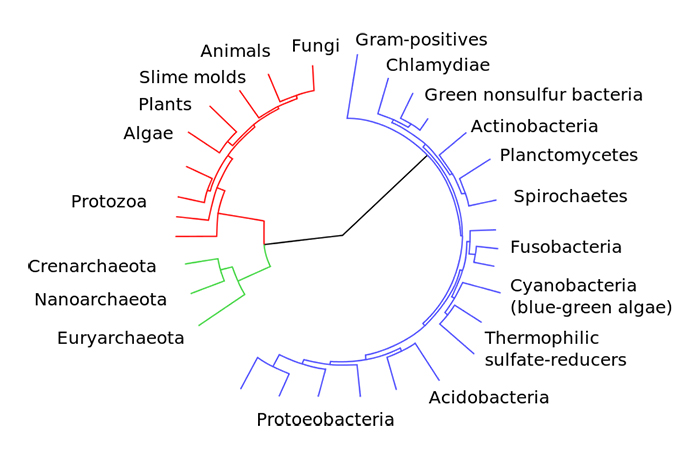

I should add that since genetic analysis has become widely available, scientists now have a much more powerful tool at their disposal which has seen massive revisions in our understanding of taxonomy. Very often species relationships are now indicated via cladograms which can show diagrammatically the genetic relationships between species which are more accurate than our assessments of similarity of characteristics alone. Scientists can now determine genetic relationships and even suggest time scales when divergence from one species into another occurred, based on changes within genomes.

A cladogram showing the phylogenetic relationships between cichlids in the genus Lepidiolamprologus. After Shelly et al., 2005.

http://research.amnh.org/scicomp/pdf…y_etal2006.pdf

So let’s get beyond the difficulties of identifying and classifying species, it’s a massively complicated matter that cannot be explained fully in a short article and indeed the complicated revisions of taxonomy and the debates in the scientific literature happen outside of the awareness and in many cases (mine included) beyond the ken of hobbyists who have not spent a lifetime in academia. For the average hobbyists it is enough to know the basics yet appreciate that there is a great deal more that can be discovered should one wish to delve further. Let us, and then explore what knowledge of binominals can do for us.

So What’s the Point?

Beyond the ‘knowledge for the sake of knowledge’ argument, I can see several benefits in knowing a species’ binominal. To return to my teacher’s argument, if we know which species is which we can make informed decisions about its care. Common names vary from country to country, aquarium store to aquarium store and hobbyist to hobbyist. Binominals can help us to more easily differentiate between very similar species, Acanthurus nigricans and Acanthurus japonicus are both offered for sale as Gold-rimmed Tangs or White-cheeked Surgeons and so forth, but the survival rate of A. japonicus is far better in the home aquarium according to many authors.

Or perhaps you may be reading about a species but do not have an image available, increasingly unlikely these days admittedly, but many names are descriptive and useful. If we consider the Redmargined Fairy Wrasse, its name ofCirrhilabrus rubromarginatus tells us it will be similar to others of its genus, but it will be edged in red. Similarly C. rubrisquamis will have red scales; C. rubripinniswill be red finned and so forth.

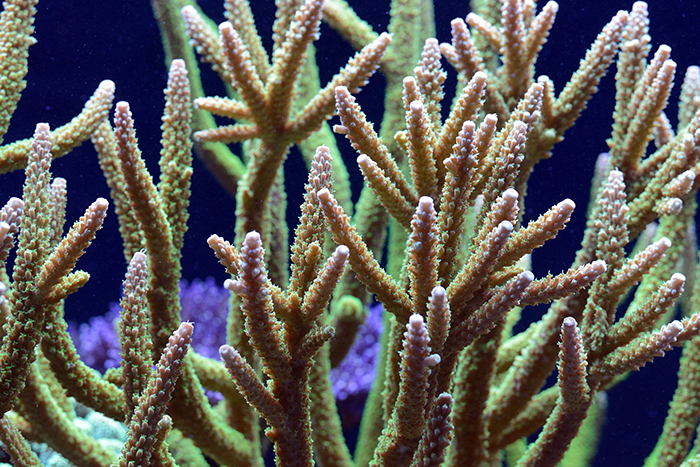

What about inverts? I’ve focused on fishy examples, but the same rules apply to inverts, though naming them might be a lot trickier for the average aquarist, we tend to use terms like ‘acroporids’ or Acropora sp. a lot. Incidentally Acropora hails from the Greek acro ‘on top off’ and pora meaning ‘small hole’, referring to the polyps’ position on the main skeleton.

What about inverts? I’ve focused on fishy examples, but the same rules apply to inverts, though naming them might be a lot trickier for the average aquarist, we tend to use terms like ‘acroporids’ or Acropora sp. a lot. Incidentally Acropora hails from the Greek acro ‘on top off’ and pora meaning ‘small hole’, referring to the polyps’ position on the main skeleton.

A major benefit to knowing scientific names is the indication that one species will have similar biology, morphology, growth pattern, feeding behaviour and care requirements of other species in the genus. Congeners as they are known, don’t always share every character, but enough similarity will be present that will allow in the overwhelming number of cases for comparison to be drawn between them.Ctenochaetus species feed in the same manner for example, Acanthurids are typically territorial and fishes from the genus Chromis are typically small and show shoaling behaviour (admittedly not always in captivity). If you know one species, the chances are that knowledge will be applicable to another in the same genus.

Knowledge of taxonomic structure can inform us on other levels, if we know that a species is the only member of its genus then there is something remarkable about it and cannot be closely compared to others within its family. The example of the Regal Tang is relevant here as is the example of the Maroon Clown. Premnas biaculeatus is the only species in this genus and is markedly different to the rest of the clowns in the Amphiprionae. If we came across it at a store with no knowledge of the species we might conclude it was a clown like all the others, yet it consistently grows larger than the Amphiprion species – a useful thing to know.

Taking this example further- if we look at the subgenera within the Amphiprion genus we can see that species within the subgenus Phalerebus (skunk complex) will all share morphological similarities as will species within the other subgenera.

There is also a tendency within the fish world to spout binominals at length, sometimes this is just the manner of the person doing the spouting, and other times I think it might just be a tendency to show off. This can be baffling to novices or annoying to those who just prefer plain speaking, at least if you know the names you can turn round to a show-off and let them know you can play in the same league.

Writing Binominal Names

The ‘governing body’ of binominal nomenclature, the organization that ‘sets the rules’ is the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature, their code, the ICZN Code has been created to ‘regulate’ and to some extent enforce the rules. Personally I find a lot of the literature on the subject very heavy going and for the purposes of those of us who are less involved in the detail; the following is a useful summary.

-Binominals are written in italics, the genus is always capitalized the specific is not (Older works may not adhere to this convention). Should the body of the text be in italics the binominal is written in non-italicized font. When handwritten the binominal is underlined.

-In descriptions and articles the binominal is often appended with the first author(s) to describe the species and the date, this is usually placed in parentheses.Paracheilinus carpenteri (Randall & Lubbock, 1981), for example.

-Species named after a person, place or other proper noun are not capitalized, even though this may upset your spell checker.

-Hybrids are referred to using a ‘x’, such as Paracheilinus carpenteri x angulatus.

-When discussing several species of the same genus, the genus name can be indicated by its capital alone, but only after it has been written in full previously. C. carpenteri, for example.

-When discussing a group of species in general or an unknown species an author may use ‘sp.’, Paracheilinus sp. or ‘spp.’ as a plural for example. This is not be confused with the epithet ssp., which means subspecies or indeed sspp., for several subspecies.

-Other epithets tend to crop up, such as ‘var.’ For variety, ‘agg.’, for species aggregation, Genus and other ranking names, when written alone, are not always italicized, but it is common practice.

-As we are dealing with zoology the term binominal should be used to be 100% accurate, in botany the term binomial is used, though many zoologists do not stick to this convention. There are also some minor differences in how zoological and botanical codes are applied.

Getting a Species Named After You

You can name a species after yourself, as I understand it, but it is considered bad form, but you can name it after a colleague, fellow researcher, patron, benefactor or indeed anyone you should wish, within reason. Derogatory names are generally frowned upon, though there are slime mould beetles named after George W. Bush, **** Cheney and Darth Vader. On a more lighthearted note there are two fish named after Douglas Adams’ characters: the cod-like Fiordichthys slartibartfastifrom New Zealand and another New Zealand species, Bidenichthys beeblebroxi. It would appear Chris Paulin, their describer, has a penchant for quirky British sci-fi comedy.

Latinizing names can be difficult to understand if like me you struggle with (or have forgotten) Latin grammar, in the majority of cases though names are Latinized and then given gender endings: (-ae for a woman, -I for a man, –arum for more than one woman, -orum for a group of more than one man or a mixed group.

In the main though, fish names are rational and sensible and named after a species’ physical characteristics. When named after a person they are named to honor the great and the good in fish identification and very often named after the person who collected the original specimen as recognition of their contribution to science. It is no surprise we see many fish named randalli, bleekeri, rainfordi, debelius and so forth. A recent trend though has seen organizations ‘selling’ the rights to a species name when new species are discovered – this can fund scientific works and presumably funds new exploration and species discovery.

A sensibly named fish, Halichoeres biocellatus. Halichoeres means ‘salt pig’ and refers to the fishes’ pig-like snout and biocellatus refers to the two ‘eye’ spots.

The Problem with the Evolutionary Tree

Before I go though, permit me a rant:

Many writers including the late Stephen J. Gould wrote at length about the faults inherent in the evolutionary tree idea, often presented in graphical form as a tree-like structure with humanity standing proudly at the top of this seemingly preordained rise form ‘lower’ to ‘higher’ life forms. Personally I accept evolution by natural selection as my woirld view, so reject this paradigm quite strongly. Not only is it incorrect, in my opinion, but it suggests that the ‘higher’ organisms are superior and somehow more ‘evolved’. Modern analysis tells us this is simply not true.

In reality humans, even vertebrates as a whole are just a ‘spur from a branch’ and modern techniques show just how evolved we actually are at a cellular and genetic level.

A modern understanding – diagrammatic representation of the divergence of modern taxonomic groups from their common ancestor. Photo by Wiki Commons.

Does this matter? Well, yes, it has done. When placental mammals colonized Australia with the help of humans it was considered acceptable at the time as they were naturally more advanced than the native marsupials and monotremes they displaced – this was the natural order.

It also underpins many fallacies about species and groups which apparently ‘have remained unchanged since the dawn of time’ and other unscientific phrases used to describe sharks for example. We still see terms such as ‘primitive’ used to describe species such as lampreys (even you Mr. Attenborough), with the implication that they are somehow less evolved and have skulked around the roots of the tree of life for the last few million years doing very little whilst we ‘advanced’ life forms have forged ahead.

This is problematic in my opinion, all species are evolved to be the ‘fittest’, to most closely fit into their habitat (rather than the strongest), and all are equally valuable in a scientific sense. ‘Primitive’ species should be considered as evolutionary success stories with characteristics (and genomes), that are highly durable. It remains up to us ‘higher’ organisms to decide if they are valuable in any further way.

We often read of species such as the Coelacanth or the Gingko tree as being ‘living fossils’; yes they share traits with ancestors that are now extinct, but that doesn’t mean they have been in evolutionary stasis for millions of years and if they have not deviated as far from a shared ancestor as other ‘higher’ organisms it doesn’t place them as being lesser in any way. Selection pressure has meant they have retained useful characteristics.

Rant over. As you can see the subject of taxonomy is complex, subject to human preconceptions, vagaries and personalities. It is though fascinating and should you wish to explore further can offer a deeper understanding of our hobby that I would recommend to all. I also apologize if I have made any errors in terms of binominals – people keep changing things!

Glossary of Terms

Here’s a short list that may prove useful – you may never see scientific names the same way.

Colors are an easy starting point:

NB – depending on the gender of the character being described the color may take a different word ending: ruber, rubra, rubrum for example.

NB – depending on the gender of the character being described the color may take a different word ending: ruber, rubra, rubrum for example.

Other commonly used terms:

0 Comments