By Ret Talbot

It was late December 2008, and Dr. Andrew Rhyne of Roger Williams University and New England Aquarium, was braving a New England snowstorm to get the data. Some four years earlier, a coral reef ecologist named Dr. Andrew Bruckner, who, at the time, was working with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), had set out on a mission to better quantify the actual volume and diversity of the marine aquarium trade. Bruckner’s work was part of a larger NOAA initiative to improve conservation, management, and restoration actions for coral reefs, and while he was able to analyze some of the aquarium trade data, Bruckner neither had the time, nor resources, to perform a comprehensive trade analysis.

Dr. Andrew Rhyne and his colleagues from New England Aquarium are taking a closer look at the trade in marine aquarium fishes, and the data they are producing could be a game-changer.

Rhyne did. So Bruckner sent him 12 boxes of raw data that would become the first real credible published data on the global trade in marine aquarium fishes.

A Snowstorm of Data

“It’s a funny story,” says Rhyne seven years after that snowstorm. The boxes of data Bruckner sent had arrived at Rhyne’s Roger Williams lab, but Rhyne was at home—a good 45 minutes from his lab in good weather. It was snowing hard, and Rhyne’s wife warned him not to make the trip. “She told me ‘You’ll run off the road and get hurt,’” Rhyne recalls, but all he could think about was getting the 12 boxes and getting started working on it.

So off he headed into the snowstorm.

The data sitting in Rhyne’s lab were import paperwork that Bruckner had started to collect in 2004 from the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). When shipments of wildlife arrive at US ports of entry, it is USFWS’s job to clear the shipments and record import data in the Law Enforcement Management Information System (LEMIS) database. Unfortunately, USFWS records all non-CITES listed marine aquarium fishes in LEMIS under a single code: MATF, for marine tropical fish. So while LEMIS provides data on trade volume, it doesn’t say anything about the diversity of species imported. In addition, LEMIS relies heavily on self-declared import data, and short of individual inspection, there is little opportunity to identify errors. Bruckner knew he needed better data.

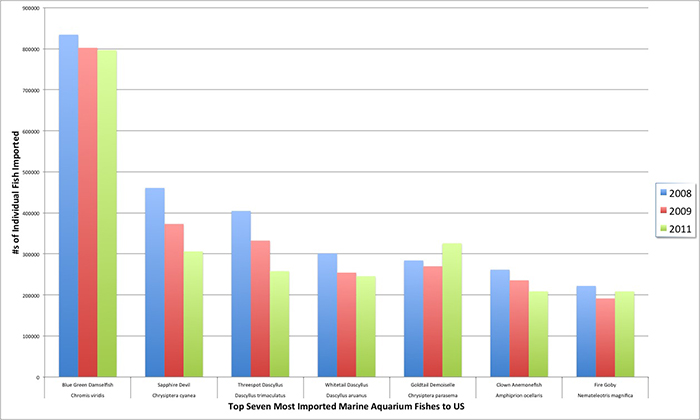

The seven most imported species of marine aquarium fishes to the US represent almost 33 percent of the overall import volume.

In addition to the declaration paperwork that accompanies imported wildlife shipments, there are also commercial invoices attached to each shipment. Bruckner realized these invoices were a much better representation of trade than the LEMIS data because the invoices generally record fishes down to the species level. Unfortunately, while the commercial invoices were archived by USFWS, they were not digitized, necessitating a massive amount of challenging data entry—hence Rhyne’s eagerness to brave a snowstorm to get his hands on the 12 boxes of commercial invoices and begin.

Fifteen minutes after leaving his house, Rhyne was calling his wife to tell her he had run off the road, barely missed a telephone pole, and had to be pulled out of snowbank by a guy in a truck. “I told you,” Rhyne recalls his wife saying. “If you damaged my car you’re toast.”

Technology to the Rescue

I-told-you-so’s and the wisdom of wives aside, Rhyne got the data and started the process of entering it. Very quickly, however, he learned that the project, which was now a joint project between Roger Williams and New England Aquarium with support from NOAA, was much, much larger than even he had imagined. Even with a team of Roger Williams students on hand to enter data, the project continued to grow with more than 20,000 invoices, some of which were 20 pages in length. It wasn’t only the amount of data that need to be entered into the database, but it was also the quality of that data from a readability standpoint. Poor quality faxed invoices, smudged documents and poor handwriting all made the job more difficult, and that’s not even taking into account the outright errors and inconsistencies in common and species names.

n order to process the documents, Rhyne realized he needed a more powerful tool, and he ultimately turned to optical character recognition (OCR) software customized for wildlife shipments. Using the OCR software, Rhyne and his team were able to relatively quickly capture shipment information from the declaration documents, as well as species and quantity information from the invoices. The software was able to check species names against databases of taxonomically correct names and highlight potential errors or even fix simple mistakes such as an exporter using a junior synonym or misspelling a scientific name. The process wasn’t lightning fast, as each document still had to be scanned, read and then imported into the database, but it made the task manageable and resulted in the 2015 publication of the publically available online database Marine Aquarium Biodiversity and Trade Flow.

n order to process the documents, Rhyne realized he needed a more powerful tool, and he ultimately turned to optical character recognition (OCR) software customized for wildlife shipments. Using the OCR software, Rhyne and his team were able to relatively quickly capture shipment information from the declaration documents, as well as species and quantity information from the invoices. The software was able to check species names against databases of taxonomically correct names and highlight potential errors or even fix simple mistakes such as an exporter using a junior synonym or misspelling a scientific name. The process wasn’t lightning fast, as each document still had to be scanned, read and then imported into the database, but it made the task manageable and resulted in the 2015 publication of the publically available online database Marine Aquarium Biodiversity and Trade Flow.

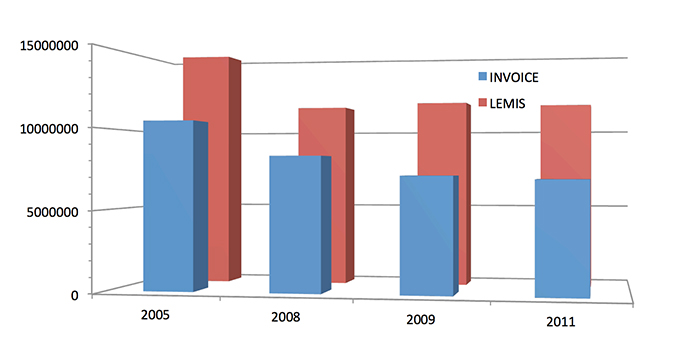

The database proved its utility to government agencies and fisheries managers before it was even officially published. Data contained in the database were instrumental in the National Marine Fisheries Service’s (NMFS) decision to not list either the orange clownfish (Amphiprion percula) or the green chromis (Chromis viridis) under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). The database was also instrumental in the decision to list the Banggai cardinalfish as “threatened” rather than “endangered” under the ESA. While the data contained in LEMIS may be useful to law enforcement when enforcing compliance at the point of import or export, they fail to provide a useful tool for assessing the trade. For example, knowing that 11,229,443 marine aquarium fishes were imported to the US in 2005 is interesting, but it does little to help wildlife managers assess the effects of the trade on ecosystems (e.g., fishery sustainability, invasive species introductions, etc.). As Rhyne and his colleagues point out, the need for accurate data continually increases, but the methods used to monitor trade have remained largely static.

What the Data Show

The database provides the first significant snapshot of the marine aquarium trade in terms of numbers of species traded, overall volume and countries of origin. It includes invoice data from 2008, 2009 and 2011, as well as modeled data from several earlier years. The data show a decreasing trend in imports from nearly 8,300,000 individual marine aquarium fishes imported to the US in 2008 to just shy of 6,900,000 fish imported in 2011. These import numbers are all shown to be significantly down from the 2005 high of more than 11 million fishes imported, likely a result of the economic downturn.

The database also shows that 45 countries exported marine aquarium fishes to the US between 2008 and 2011. Imports from the Philippines were the largest by far, representing 56 percent of overall trade volume (12,732,212 fishes over the three years). Indonesia was the second largest source country with 28 percent of volume (6,331,781 fishes over the three years). Almost 640,000 fishes were imported from Sri Lanka, putting it in third place.

The database also shows that 45 countries exported marine aquarium fishes to the US between 2008 and 2011. Imports from the Philippines were the largest by far, representing 56 percent of overall trade volume (12,732,212 fishes over the three years). Indonesia was the second largest source country with 28 percent of volume (6,331,781 fishes over the three years). Almost 640,000 fishes were imported from Sri Lanka, putting it in third place.

In terms of species diversity, the data reveal the tremendous biodiversity of the trade, showing that, across the three-year period, 2,278 unique species were imported to the US. Despite the overall high biodiversity, the data show that 52 percent of imports are represented by just 20 species. The green chromis was the number one most imported species, representing more than 10 percent of total imports. According to the database, as many as 16 different countries exported the green chromis to the US. The next six most imported species remained consistent in rank across the years studied. These top seven species represent almost 33 percent of overall import volume.

The data collected and analyzed by Rhyne and his colleagues reveal that the volume of marine aquarium fish imports recorded in LEMIS are over-reported by as much as 40 percent.

The data also reveal errors in commonly cited LEMIS data on the volume of marine aquarium fishes entering the US. Through the work of Rhyne and his collegaues, they showed that the volume of marine aquarium fish imports recorded in LEMIS were over-reported by as much as 40 percent. By looking at the invoices accompanying the declaration forms, the researchers discovered situations where entire shipments were misclassified as MATF when the shipment actually contained only freshwater fishes. By looking at the invoices, they also found that “wild caught” and “aquacultured” animals were commonly mislabeled in LEMIS.

Taking the Tools on the Road

Rhyne and his colleagues maintain that the general lack of specific data systems for recording the actual volume and diversity of species imported for the marine aquarium trade raises serious issues. Given how few current data are available, how can the trade assess how far along the path to sustainability it is, and how can it answer critics who allege unsustainability? Perhaps even more important, how can the US government effectively monitor the trade and the risks it poses without data? Put another way, given the ever-increasing attention that non-native and endangered species are receiving, isn’t it easier for the government to simply shut down portions of the trade if there are not credible third party data on which to base decisions?

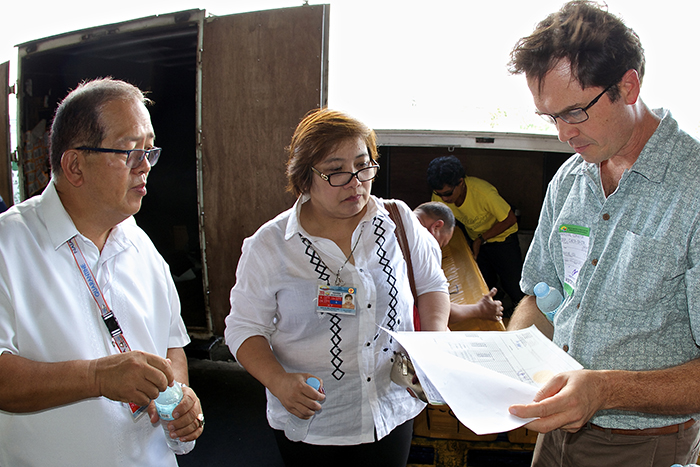

The system that Rhyne and his colleagues have developed is well poised to assist both the US government and foreign governments in monitoring the trade in not just marine ornamentals but in all wildlife. In March of 2015, the Philippine Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) signed a memorandum of understanding with the New England Aquarium to implement the tools used to create the Marine Aquarium Biodiversity and Trade Flow database in the Philippines. In November of 2015, Rhyne travelled to the Philippines to install hardware and software and train BFAR staff on its use. The result of the collaboration, which is largely funded by a NOAA grant, will be one full year of Philippine export data, providing for the first time a glimpse into the marine aquarium trade in the largest source country.

Rhyne at the BFAR office in Cebu, Philippines.

The collaboration between BFAR and New England could be a game-changer for the marine aquarium trade. In addition to collecting data, the tools Rhyne and his colleagues are working to implement could provide for real time monitoring of trade that will assist wildlife inspectors at ports of entry and export. The data themselves will allow for objective risk assessment and provide real numbers on which trade sustainability can be assessed. Without this data, the marine aquarium trade will have to rely largely on anecdote, which frequently is not sufficient to respond to trade critics.

So why not embrace the data and the efforts to collect more of it? Certainly more credible data will reveal areas of trade that need reform, but not getting the data because of fear of what they may show is not a viable solution. A forward-looking marine aquarium trade should be just as interested as wildlife inspectors, law enforcement and even trade critics in identifying illegal activity, lack of sustainability and areas where improvement is necessary. Data can be the foundation upon which to build a truly sustainable aquarium trade of the future that can realize its potential as a force for good, while at the same time providing enjoyment and inspiration for millions of aquarists worldwide.

A banka awaits the dawn of a new day in the Philippines. Photo by J. C. Delbeek.

0 Comments