Last time, in Part 1 of this series, we reviewed technical terms useful in the understanding of coral coloration. We learned there are many different categories of colorful or fluorescent pigments, and these pigments can be further divided into classes (or clades) where ancestral origins are important in classification tools.

The most common fluorescent pigments are green. Note the granular appearance of the green fluorescent chromophores within this coral’s tissues. Photo by the author.

This month, we’ll look at the most populous coral pigment category: Green Fluorescent Proteins (or GFPs). In addition, we’ll examine how light intensity and spectral qualities affect GFPs. It is important to note that some GFPs can be converted by light to other colors (especially orange or red fluorescence). An examination of photoconversion will be part of this month’s installment.

To make things easier if you’re not familiar with the terminology, I’ll present the glossary once more:

Glossary

- Absorbance:

- Ability of a solution or layer of a substance to retain light without reflection or transmission.

- Absorption:

- The process in which incident radiation is retained without reflection or transmission.

- Brightness:

- The intensity of a fluorescent emission. Extinction coefficient times Quantum Yield = Brightness.

- Clade:

- For our purposes in this article, a grouping of pigments based on similar features inherited from a common ancestor. Pigments from corals includes Clades A, B, C, and D. Clades can refer to living organisms as well (clades of Symbiodinium – zooxanthellae – are a good example.)

- Chromophore:

- The colorful portion of a pigment molecule. In some cases, chromophore refers to a granular packet containing many pigment molecules.

- Chromoprotein pigment:

- A non-fluorescent but colorful pigment. These pigments appear colorful because they reflect light. For example, a chromoprotein with a maximum absorption at 580nm might appear purple because it preferentially reflects blue and red wavelengths.

- Chromo-Red Pigment:

- A newly described type of pigment possessing characteristics of both chromoproteins and Ds-Red fluorescent proteins. Peak fluorescence is at 609nm (super red).

- Cyan Fluorescent Protein (CFP):

- Blue-green pigments with fluorescent emissions in the range of ~477-500nm. Cyan and green pigments share a similar chromophore structure. Cyan pigments are expressed at lower light levels than green, red or non-fluorescent pigments.

- Emission:

- That light which is fluoresced by a fluorescent pigment.

- Extinction Coefficient:

- The quantity of light absorbed by a protein under a specific set of circumstances.

- Excitation:

- That light absorbed by a fluorescent pigment. Some of the excitation light is fluoresced or emitted at a less energetic wavelength (color).

- Ds-Red type pigment:

- A type of red fluorescent pigment with a single primary emission bandwidth at 574-620nm. Originally found in the false coral Discosoma.

- Fluorescence:

- Absorption of radiation at one wavelength (or color) and emission at another wavelength (color). Absorption is also called excitation. Fluorescence ends very soon after the excitation source is removed (on the order of ~2-3 nanoseconds: Salih and Cox, 2006).

- Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP):

- Fluorescent pigments with emissions of 500-525nm.

- ‘Hula Twist’:

- A bending of a pigment molecule resulting in a change of apparent color. Molecular bonds are not broken; therefore the pigment can shift back and forth, with movements reminiscent of a hula dancer.

- Kaede-type pigment:

- A type of red fluorescent pigment with a characteristic primary emission at ~574-580nm and a secondary (shoulder) emission at ~630nm. Originally found in the stony coral Trachyphyllia geoffroyi, but common in corals of suborder Faviina.

- Kindling Protein:

- A protein capable of being converted from a non-fluorescent chromoprotein to a fluorescent protein. Sometimes called a ‘Kindling Fluorescent Protein’, or KFP.

- Quantum Yield:

- Amount of that energy absorbed which is fluoresced. If 100 photons are absorbed, and 50 are fluoresced, the quantum yield is 0.50.

- Photobleaching:

- Some pigments, such as Dronpa, loss fluorescence if exposed to strong light (in this case, initially appearing green and bleaching to a non-fluorescent state when exposed to blue-green light). Photobleaching can obviously cause drastic changes in apparent fluorescence. In cases where multiple pigments are involved, the loss of fluorescence (or energy transfer from a donor pigment to an acceptor pigment) could also result in dramatic shifts in apparent color.

- Photoconversion:

- A rearrangement of the chemical structure of a colorful protein by light. Depending upon the protein, photoconversion can increase or decrease fluorescence (in processes called photoactivation and photobleaching, respectively). Photoconversion can break proteins’ molecular bonds (as with Kaede and Eos fluorescent pigments) resulting in an irreversible color shift, or the molecule can be ‘twisted’ by light energy (a ‘hula twist’) where coloration reversal are possible depending upon the quality or quantity of light available. This process is known as photoswitching).

- Red Fluorescent Protein (RFP):

- Those pigments with an emission of ~570nm and above. Includes Ds-Red, Kaede and Chromo-Red pigments.

- Stokes Shift:

- The difference in the maximum wavelength of fluorescent pigment excitation light and the maximum wavelength of the fluoresced light (emission). For example, a pigment with an excitation wavelength of 508nm and an emission wavelength of 535nm would have a Stokes Shift of 27nm.

- Threshold or Coloration Threshold:

- The point at which pigment production is sufficient to make its fluorescence (or in the case of non-fluorescent chromoproteins, it absorption) visually apparent. The term threshold generally refers pigment production, although, in some cases, it could apply to a light level where a pigment disappears (as in the cases of photobleaching, or photoconversion).

- Yellow Fluorescent Protein:

- An uncommon group of fluorescent proteins with emissions in the 525-570 nm range (Alieva et al., 2008).

Types of Pigments

There are at least 9 described types of coral pigments. Note: Pigment types, such as green or red might not be structurally similar to another green or red pigment in a different clade – see below). These include:

- Cyan Fluorescent Proteins (CFP) – Cyan pigments are blue-green pigments with a maximum emission of up to ~500 nm. The chromophore structure of a cyan pigment is very similar to that of a green fluorescent pigment.

- Green Fluorescent Proteins (GFP) – This group, by far, is the most numerous of the fluorescent proteins. The structure of green fluorescent chromophores is very similar to that of cyan fluorescent chromophores.

- Yellow Fluorescent Proteins (YFP) – An unusual type of fluorescent protein with maximum emission in the yellow portion of the spectrum. Rare in its biological distribution, YFP is found in a zoanthid and some specimens of the stony coral Agaricia. Personally, I’ve noted yellow fluorescence in a very few stony corals (Porites specimens) here in Hawaii while on night dives using specialized equipment to observe such colorations (see www.nightsea.com for details on this equipment).

- Orange Fluorescent Protein (OFP) – I’ve included this protein ‘type’ in an attempt to avoid confusion. OFP is used to describe a pigment found in stony coral Lobophyllia hemprichii and its name suggests a rather unique sort of protein. In fact, OFP is simply a variant of the Kaede-type fluorescent proteins.

- Red Fluorescent Proteins (RFP) – A group of proteins including several different subtypes (Kaede, Ds-Red and Chromo-Red). Typically, fluorescent emission is in the range of ~580 nm to slightly over 600 nm.

- Dronpa – A green fluorescent protein that loses fluorescent when exposed to blue-green light (~490 nm) but returns when irradiated with violet light at ~400 nm.

- Kindling Proteins – A protein (notably from the anemone Anemonia sculata) that changes from a non-fluorescent pigment to one demonstrating fluorescence. This change is switchable/reversible and its state depends upon the spectral quality of light striking it.

- Chromo-Red Proteins – A new classification (Alieva et al., 2008) of a single fluorescent pigment found in the stony coral Echinophyllia. This chromo-red pigment has qualities of a non-fluorescent chromoprotein, but fluoresces at a maximum of 609 nm.

- Chromoproteins (CP) – This group of pigments is non-fluorescent, or has minimal fluorescence (where the quantum yield is essentially zero). Instead of relying upon fluorescence for coloration, these pigments instead absorb light most strongly in a relatively narrow portion of the visible spectrum. Most coral chromoproteins absorb light maximally at 560-593 nm. There are reports of anemones absorbing light at a maximum wavelength of 610nm, and a couple of reports of stony corals absorbing wavelengths in the 480-500nm range. Some chromoproteins are very similar in structure to the fluorescent Ds-Red proteins. In fact, genetic engineers have found that a single amino acid substitution in a protein can make the difference between non-fluorescence and fluorescence. Chromoproteins do not get much attention by researchers (relative to that of fluorescence proteins) and there are only about 40 described.

| Species | Pigment Name | Type | Suborder | Excit. | Emission | Clade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acropora aculeus | aacuGFP1 | GFP | Astrocoeiina | 478 | 502 | C2 |

| Acropora aculeus | aacuGFP2 | GFP | Astrocoeiina | 502 | 513 | C2 |

| Acropora eurostoma | AeurGFP | GFP | Astrocoeiina | 504 | 515 | C2 |

| Acropora millepora | amilGFP | GFP | Astrocoeiina | 503 | 512 | C2 |

| Acropora millepora | amilFP512 | GFP | Astrocoeiina | 500 | 512 | ? |

| Acropora nobilis | anobGFP | GFP | Astrocoeiina | 502 | 511 | C2 |

| Agaricia fragilis | afraGFP | GFP | Fungiina | 494 | 503 | D |

| Anemonia sculata | asFP499 | GFP | Actinaria | ? | 499 | A |

| Catalaphyllia jardineri | cjar | GFP | Faviina | 509 | 517 | D |

| Condylactis gigantea | cgigGFP | GFP | Actinaria | 399/482 | 496 | A |

| Dendronephthya sp. | dendGFP | GFP | Alcyonaria | 494 | 508 | D |

| Discosoma sp. | dis3GFP | GFP | Corallimorpharia | 503 | 512 | D |

| Echinophyllia echinata | eechGFP1 | GFP | Faviina | 497 | 510 | D |

| Echinophyllia echinata | eechGFP2 | GFP | Faviina | 506 | 520 | D |

| Echinophyllia echinata | eechGFP3 | GFP | Faviina | 512 | 524 | D |

| Eusmilia fastigata | efasGFP | GFP | Meandriina | 496 | 507 | C1 |

| Favites abdita | fabdGFP | GFP | Faviina | 508 | 520 | D |

| Galaxea fascicularis | gfasGFP | GFP | Meandriina | 492 | 506 | D |

| Galaxea fascicularis | Azami-Green | GFP | Meandriina | 492 | 505 | D |

| Heteractis crisperi | hcriGFP | GFP | Actinaria | 405/481 | 500 | A |

| Lobophyllia hemprichii | Eos | GFP | Faviina | 506 | 516 | D |

| Lobophyllia hemprichii | lhemOFP | GFP | Faviina | 507 | 517 | D |

| Meandrites meandrina | mmeanGFP | GFP | Faviina | 487 | 515 | C1 |

| Montastraea annularis | monannGFP | GFP | Faviina | ? | 510 | D |

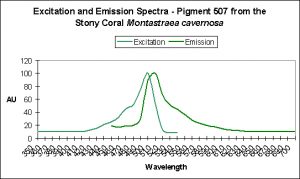

| Montastraea cavernosa | mcavRFP | GFP | Faviina | 504 | 517 | D |

| Montastraea cavernosa | mcavGFP | GFP | Faviina | 506 | 516 | D |

| Montastraea cavernosa | P-510 | GFP | Faviina | 440 | 510 | D |

| Montastraea cavernosa | mcav2 | GFP | Faviina | 505±3 | 515±3 | D |

| Montastraea cavernosa | mcav3 | GFP | Faviina | 505±3 | 515±3 | D |

| Montastraea cavernosa | mcav4 | GFP | Faviina | 505±3 | 515±3 | D |

| Montastraea cavernosa | mcav6 | GFP | Faviina | 495 | 507 | D |

| Montastraea cavernosa | r2 | GFP | Faviina | ? | 522 | D |

| Montastraea cavernosa | r3 | GFP | Faviina | ? | 514 | D |

| Montastraea cavernosa | r4 | GFP | Faviina | ? | 519 | D |

| Montastraea cavernosa | r7 | GFP | Faviina | ? | 505 | D |

| Montastraea cavernosa | g1.2 | GFP | Faviina | ? | 518 | D |

| Montastraea cavernosa | g4 | GFP | Faviina | ? | 518 | D |

| Montastraea cavernosa | g6 | GFP | Faviina | ? | 507 | D |

| Montastraea faveolata | monfavGFP1 | GFP | Faviina | 440 | 510-520 | D |

| Montipora digitata | mdigFP514 | GFP | Astrocoeiina | 508 | 514 | ? |

| Montipora efflorescens | meffGFP | GFP | Astrocoeiina | 492 | 506 | C3 |

| Pectiniidae | Dronpa | GFP | Faviina | 503 | 518 | D |

| Platygyra lamellina | plamGFP | GFP | Faviina | 502 | 514 | D |

| Porites porites | pporGFP | GFP | Faviina | 495 | 507 | C3 |

| Ricordea florida | P-510 | GFP | Corallimorpharia | ? | 510 | D |

| Ricordea florida | P-513 | GFP | Corallimorpharia | ? | 513 | D |

| Ricordea florida | P-517 | GFP | Corallimorpharia | 506 | 517 | D |

| Ricordea florida | rfloGFP | GFP | Corallimorpharia | 508 | 518 | D |

| Ricordea florida | P-520 | GFP | Corallimorpharia | ? | 520 | D |

| Sarcophyton sp. | sarcGFP | GFP | Octocorallia | 483 | 500 | D |

| Scolymia cubensis | scubGFP1 | GFP | Faviina | 497 | 506 | D |

| Scolymia cubensis | scubGFP2 | GFP | Faviina | 497 | 506 | D |

| Stylocoeniella sp. | stylGFP | GFP | Astrocoeiina | 485 | 500 | C2 |

| Trachyphyllia geoffroyi | P-518 | GFP | Faviina | 508 | 518 | D |

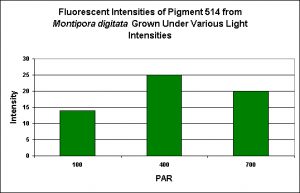

Figure 1. Light intensity and its effects on fluorescent intensity. Light was generated by a 13,000 K metal halide lamp. After D’Angelo et al., 2008.

Effects of Light Intensity and Spectral Quality on GFPs

The following information is derived mostly from the work of D’Angelo et al. (2008). It offers fascinating insights into some of the factors required to promote production of fluorescent pigments in corals. The primary investigator in the D’Angelo experiments was Dr. Joerg Wiedenmann, and he was kind enough to supply information about their lighting experiments. The high/low light trials were conducted using a 400-watt Aqua Medic Aqualine 13,000K metal halide lamp. The color experiments used two lamps. For the green and red filters, a 250-watt Osram Powerstar HQI-TS Daylight metal halide was employed. The blue filter was used in conjunction with a 250-watt BLV 20,000K Nepturion metal halide lamp. PAR intensity was standardized at 200 µmol·m²·sec in these experiments. Thank you Dr. Wiedenmann for this additional data!

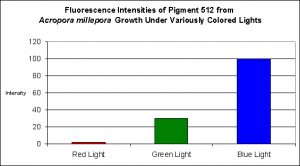

Figure 2. Effects of light color on Acropora millepora’s fluorescent Pigment 512. Light intensity was 200 µmol·m²·sec in each of the treatments. After D’Angelo et al., 2008.

Green Fluorescent Pigment 512

- Host: Acropora millepora

- Pigment Clade: C2

- Pigment Type: Green Fluorescent Protein

- Fluorescence Best Induced by: Blue light (but see comments below)

- Light Intensity Required: Best fluorescence at 700 µmol·m²·sec

- Photoconversion Possible: Yes (based on spectral characteristics of Acropora tenuis, below and observations of other pigments found in Acropora millepora).

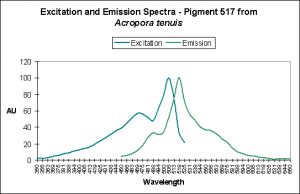

Photoconversion is only seldom reported in scientific literature among corals containing Clade C pigments. Based on information offered by Papina et al. (2002), we could conclude that photoconversion does occur in Clade C2 pigments (found mostly in Acropora species). While Papina’s data suggests photoconversion occurs in Acropora tenuis’ Pigment 517, we see further evidence that it occurs in Acropora millepora, where exposure to Ultraviolet-A radiation enhances by two-fold the fluorescence of Pigment 513.

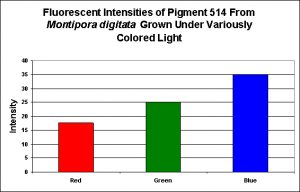

Green Fluorescent Pigment 514

- Host: Montipora digitata

- Pigment Clade: Unknown, but possibly C3

- Pigment Type: Green Fluorescent Protein

- Fluorescence Best Induced by: Blue light

- Light Intensity Required: Best fluorescence at 400 µmol·m²·sec

- Photoconversion Possible: Unknown, but unlikely.

Photoconversion

Photoconversion – the rearrangement of a chromophore by light energy resulting in shifts in perceived coloration – is known to occur in quite a number of green fluorescent pigments.

Photoconversion of GFPs to Kaede Pigments

Figure 5. Effects of light color on generation of a green pigment of the popular aquarium color Montipora digitata.

Nature loves to confound us, and the conversion by light energy of one pigment to one of a different fluorescent emission certainly falls into this category. Photoconversion can occur in many pigments but is most well documented in those pigments classified as Kaede pigments. These are found mostly in suborder Faviina (which includes about 60 stony coral genera, including Catalaphyllia, Favia, Lobophyllia, Montastraea, Mycedium, Trachyphyllia and others), but also occurs in some soft corals (Dendronephthya sp.), and false corals(Ricordea).

The photoconversion from green to orange/red Kaede pigments requires blue light (see Table 2).

| From | To | Host | Clade/Pigment | Activator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-505 | 508/572 | Montastraea cavernosa | D | ? – But most likely blue light |

| P-505 | 506/566 | Ricordea florida | D | ? – But most likely blue light |

| P-508 | 575 | Dendronephthya sp. | D | Blue Light @ 488nm |

| P-508 | 575 | Dendronephthya sp. | D | UV-A at 366nm |

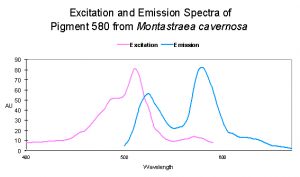

| ~516 | 582 | Montastraea cavernosa | D | Depth- light -related? |

| P-516 | 581 | Lobophyllia hemprichii | D | UV @ 390nm/Violet Light ~400nm |

| P-517 | 574 | Ricordea florida | D | UV/Violet Light |

| P-517 | 580 | Montastraea annularis | D | UV/Violet Light |

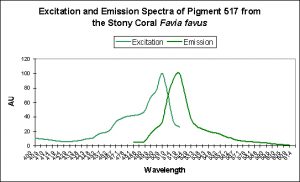

| P-517 | 593 | Favia favus | D | UV & Violet (350-420nm) |

| P-518 | 582 | Trachyphyllia geoffroyi | D | UV – Violet Light (350-410nm) |

| P-519 | 580 | Montastraea cavernosa | D | UV – Violet Light |

Figure 6. Favia favus contains a GFP that can be converted to an orange ‘Kaede’ pigment. This conversion is probably induced by ‘strong’ violet or blue light.

| From | To | Host | Clade/Pigment | Activator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-518 | None | “Pectiniidae” | D | ~490nm to bleach |

Spectral Signatures of Kaede Pigments Before and After Photoconversion

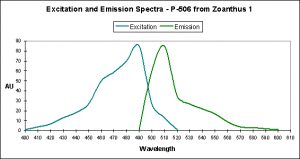

Figures 7 through 9 demonstrate the spectral characteristics of Kaede pigments before and after photoconversion are induced by violet light.

Figure 9. A case of photoconversion in progress in Ricordea florida. It is a Kaede pigment and photoconversion is likely mediated by violet/blue light. After Labas et al., 2002.

Photoconversion of GFP-like Pigments to DS-Red Pigments

Figure 10. Laboratory experiments have resulted in this pigment changing its fluorescent emission from green to yellow when substituting only 3 amino acids in the protein. However, this has not been observed in the wild.

This type of pigment was originally isolated from the corallimorpharian Discosoma, but Ds-Red type pigments are found in anemones, false corals, zoanthids and stony corals.

Photoconversion is known to occur in some Ds-Red pigments, and is most well studied in Discosoma false coral species. Interestingly, the change in fluorescent from green (emission at 500 nm) to red (emission at 583 nm) does not require light energy and can occur in darkness – this change is mediated by chemical oxidation. However, a number of conversions from red to super red and super red to blue can occur when specimens are exposed to certain light wavelengths.

Table 4. In this instance, color conversion is due to a chemical process and can occur in darkness.

| From | To | Host | Clade/Pigment | Activator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-520 | 611 | Entacmaea quadricolor | A | Chemical Oxidation |

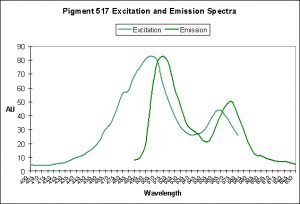

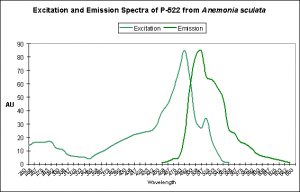

Figure 11. This pigment found in Anemonia sculata is of Clade A. Note the dual peaks and shoulders in the excitation and emission – this indicates possible photoconversion.

A Potential Case of Photoconversion: A Minor Shift of Green Fluorescence in Anemonia sculata?

Figure 11 is offered in order to demonstrate a possible case of photoconversion in an anemone species (Anemonia sculata). The dual excitation and emission peaks suggest that the pigment is in, or has possibly completed, a shift of fluorescence of about 20 nm (from 522 nm to ~550 nm).

Discussion

In both specific cases examined here, blue light induces the production of fluorescent proteins, while red light is the least effective in their production. However, we must note that light energy is not always the deciding factor in pigment production. For instance, some pigment production and/or conversion are due to chemical reactions and is independent of effects (or more properly, non-effects) of radiation – we see these cases in at least one instance involving an anemone and its Clade A pigment. Chemical oxidation may also play a part (but does not always) in color transformations see in some of the DsRed type pigments. However, where light energy is required, we should remember the light intensity categories described by D’Angelo:

- ‘Very low’ (80 µmol·m²·sec)

- ‘low’ (100 µmol·m²·sec)

- ‘moderate’ (400 µmol·m²·sec)

- ‘high’ (700 µmol·m²·sec)

- and a photoperiod of 12 hours.

The ‘very low’ and ‘low’ categories are quite easily achieved in home aquaria using modest means to produce light. The ‘moderate’ (400 µmol·m²·sec) category is found less commonly than the previous two categories. Producing this amount of light energy is quite possible when using some of the more powerful lighting sources such as metal halides, LEDs, and multiple fluorescent lamps. The highest category of 700 µmol·m²·sec is rarely seen, based on my observations. However, it is possible with selective placement of animals when using high output light sources. Bear in mind that photobleaching is possible in some pigments (for instance, the ‘Dronpa‘ pigment – see Table 3).

Lamps’ spectral characteristics are important in promoting colorful pigments. In the two specific cases we examined this month, Pigment 512 (from Acropora millepora) and Pigment 516 (from Montipora digitata), blue light is by far the most efficient in making the coral animal produce green fluorescent proteins. But there are differences – those pigments of Acropora millepora (Clade C2) are not as likely to be promoted by other bandwidths (including green and red) than the Montipora digitata pigment (of Clade C3). It is unclear if these different responses to specific colors of light are common among their respective clades, and it will be interesting to see the results of future research. We know little about the responses of Clade C1 pigments (described as being isolated from Meandrites and Eusmilia specimens). Also, recall that the light intensity for the ‘colored light’ experiments was 200 µmol·m²·sec

Photoconversion of green pigments in Clade C2 pigments is known to occur (Clade C2 pigments are most often described as being present in Acropora and Stylocoeniella species). Ultraviolet radiation is known to cause a two-fold increase in the green fluorescence of Pigment 513 (but see comments about UV in the next paragraph).

Orange Kaede pigments are found mostly – not exclusively – in corals of the suborder Faviina (but are known to occur in at least one soft coral (Dendronephthya) and the false coral Ricordea florida). Conversion of green fluorescent proteins to the Kaede type orange pigments has been observed when the animal is exposed to ultraviolet-A radiation (UV-A), and violet/blue wavelengths. Care should be taken when experimenting with dosages of UV-A in attempts to promote coloration. Most plastic ‘splash guards’ are transparent to at least some UV-A wavelengths and it is usually not necessary to deliberately increase UV-A levels in order to induce production of pigments. With this said, there is some anecdotal information (based on my personal observations) that color of at least some pigments might increase in at least some coral species when UV radiation is slightly increased.

As I mentioned, the primary investigator responded with some useful information on the types of lamps used in the D’Angelo et al. experiments, and I have the appropriate lamps and filters on order. I’m most interested in observing the characteristics of the transmitted light and I’ll report this information as it becomes available. Next time, we’ll take a closer look at orange and red fluorescent proteins, and how they are affected by light intensity and spectra.

0 Comments