Please introduce yourself, your background and how you got into the Aquarium/ Aquaculture Industry?

Ha, this might be the longest answer here. First off, hello, and thanks for your interest in Hydrospace!

My name is Kenneth Wingerter; some of you may already know me a little from my articles in Advanced Aquarist, CORAL, Tropical Fish Hobbyist, UltraMarine and Reefs magazines. As likely many in our industry can say, the roots of my company go way back into my childhood. I grew up on a farm in Standing Rock Indian Reservation, North Dakota, that was founded by my immigrant great-grandparents from Ukraine. Our land sat almost squarely on the geographic center of North America, and farmers don’t get much opportunity for extensive road trips, so I grew up utterly unfamiliar with the ocean. Despite this (or maybe because of this), I developed a keen interest in marine life at an early age. As the story goes, this culminated in my begging for a pet fish; one of my earliest memories is, in fact, of rolling around in the back of a station wagon on the way home from K-Mart (this was the 70s after all) with a bagged goldfish clutched in my arms.

Unfortunately, that goldfish bowl lasted about as long as most do. But years later, after moving to the Bismarck area, I got a shiny new 10-gallon tank (equipped with fabulously colored incandescent lighting) for my 12th birthday. I was hooked immediately; the longest I’ve ever gone without an aquarium since then was while living on a fishing vessel. I did flirt with other interests, including guitar in high school and psychology and art history in college, but the ‘aquarium thing’ always stuck.

My entrance into the aquarium industry began without much of a bang back in 1990 in a quite ordinary shopping mall LFS called Dakota Pet Center. I very much enjoyed working with the fish (and really all of the animals), but eventually had to quit after refusing to cut my mullet.

My more ‘serious’ and ‘professional’ work in the industry (no more mullet) began around 1995 while managing the aquatics department at another shop in the Bismarck area called Cunningham’s Critters & Stuff. Most notably, they were the first place in the region to carry corals, more exotic marine fish species, and pretty much anything beyond a small smattering of saltwater items. With hardly any good written instructions out there then–aside maybe from Freshwater and Marine Aquarium Magazine–most guidance for my work at that shop came from Sprung and Delbeek’s The Reef Aquarium Vol. 1, which had just recently been published. Considering that most of us had only recently relied on crushed coral and undergravel filters to maintain our relatively barren, ugly, coral-less saltwater tanks, it’s not at all hyperbolic to say that the release of this book unleashed an explosion of inspiration amongst hobbyists everywhere, including myself.

I carried this newly acquired knowledge and enthusiasm with me to the University of Oregon where I studied Biology with an emphasis on Ecology. While in college, I supported myself primarily by working more hours than I should have at a few LFSs and even a pond plant nursery. But the big turn I made professionally during that time was while working as a humble lab tech at the Zebrafish International Research Center. Here, for half a decade, my primary responsibility was cultivating and enriching live microfoods (mainly Paramecia, Moina and Turbatrix). What I initially figured would be a horrendously tedious and boring task turned out to be absolutely fascinating. But aside from how fun live feed production is, I learned how consequential it can be in a production setting.

I followed this newfound passion while undertaking postgraduate studies in the Aquarium Science Program (Newport, Oregon) where I raised a few clownfish, innumerable tubs of rotifers, and literal swimming pools full of phytoplankton as part of my practice in the Hatfield Marine Science Center.

After college, I worked mostly in hatcheries, including a marine ornamental hatchery and a trout hatchery. While the common thread in all of my aquaculture tech jobs was a focus on foods and nutrition, the rough-and-tumble vibe in these commercial facilities contrasted nicely (particularly as someone diagnosed with ADHD) with the more orderly domains of the zebrafish lab and the science center. I especially enjoyed the wildly experimental learning environment in these places.

AlgaeBarn was no exception to this, especially in the earliest days. Just like today, they were downright obsessed with improving not only production value, but quality. To this end, we were always open to trying anything. At one point, while studying picoplankton and their place in reef food webs, in search of the ultimate natural food source for copepods, I stumbled across a section in the third volume of The Reef Aquarium (2005) about purple non-sulfur bacteria (PNSB) and how promising they are as an aquaculture diet. I was blown away. I researched these organisms elsewhere. More blown away. And above all, I couldn’t believe that these extremely useful microbes were all but absent in our hobby, despite being used extensively for decades in aquaculture and wastewater facilities. I very shortly thereafter drew up a proposal to cultivate PNSB at AlgaeBarn for inhouse use (for both live feed and wastewater treatment). Well, the company was already growing and changing very rapidly by then, and my little project plan sort of slid to the back of the docket. Nevertheless, I remained enthralled by these unique microorganisms and continued to research them–rather obsessively, I’ll admit. So, when the company moved to the Denver area, I decided to stay behind, focus on PNSB, and establish Hydrospace LLC (2018).

What species/types of microbes do you cultivate?

- First generation of fully captive raised purple phototrophic bacteria and associated anaerobic microbes…

- that we collected from French Polynesia in November.

- From this, we cultivate one more generation before submitting samples for analysis to ID the species in the consortium.

- Lots of work, and lots of fun!

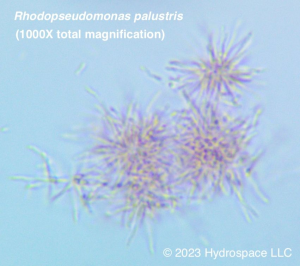

Our bread-and-butter has been Rhodopseudomonas palustris. This well-known PNSB is the sole species in our flagship product PNS ProBio™. It’s also the sole species used to make our marine snow simulation/coral food PNS YelloSno™. It shares the spotlight in our specialized marine aquarium cycling product PNS Substrate Sauce™ with another PNSB, Rhodospirillum rubrum. Those two species, as well as Rhodobacter capsulatus, are available with our grow-your-own kit: PNS HomeGro™. We have successfully cultured the ecologically über-important marine purple bacterium Roseobacter denitrificans, though failed to grow it out at a commercial scale; that’s something we consider worthy of further effort. Most recently, we selectively harvested sediment samples from three wild SPS coral-dominated sites in French Polynesia, which we used to culture a consortium of natural anaerobic reef strains. Our hope is (after determining that all members of the community are beneficial, or at least benign, and that none are pathogenic) to develop the cultures into a new product. We’d expect such a product to assist in natural carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur cycling and potentially confer some probiotic benefits as well.

Microbial ecology is a tremendously complicated subject, which makes developing truly great microbial products challenging and time-consuming, which means we’ll likely continue to focus/specialize in purple phototrophs. And that alone should always be a full plate!

How do PNS probiotics differ from conventional biofilter species (Nitrosomonas, Nitrobacter, Nitrospira, etc.)?

PNSB are absolutely different from, though complimentary to, nitrifying bacteria. Both favor marginal, though completely opposite, microhabitats: Anaerobic/illuminated and aerobic/dark, respectively. Moreover, while PNSB are heterotrophs and can thus be used to consume dissolved and particulate organic waste (yellowing compounds, detritus, etc.), nitrifiers are autotrophs and can only utilize inorganic carbon sources such as CO2 (much like algae or plants). Lastly, while the end product of nitrification is nitrate, some PNSB (e.g., Rhodopseudomonas) are capable of performing denitrification, converting excess nitrate into harmless nitrogen gas.

What are some of the benefits PNS probiotics provide the reef aquarium?

There are so many benefits that I’m often afraid to mention them all at once for fear of making it sound like some sort of ‘snake oil’ hahaha. And that would be a reasonable suspicion for sure, given the many questionable claims made by some manufacturers. But PNSB are fairly well characterized and the aquacultural application of PNSB has been exhaustively studied. They have been so thoroughly investigated that we understand their workings to the extent that we not only know, for example, how they perform denitrification, but also which genes encode for the enzymes responsible for the process. European Space Agency (ESA) engineers have incorporated Rhodospirillum as a key component of an intricate waste recovery system to be used in future crewed missions to Mars. In short, we not only know that this stuff works, but we also have a pretty good idea of how it works.

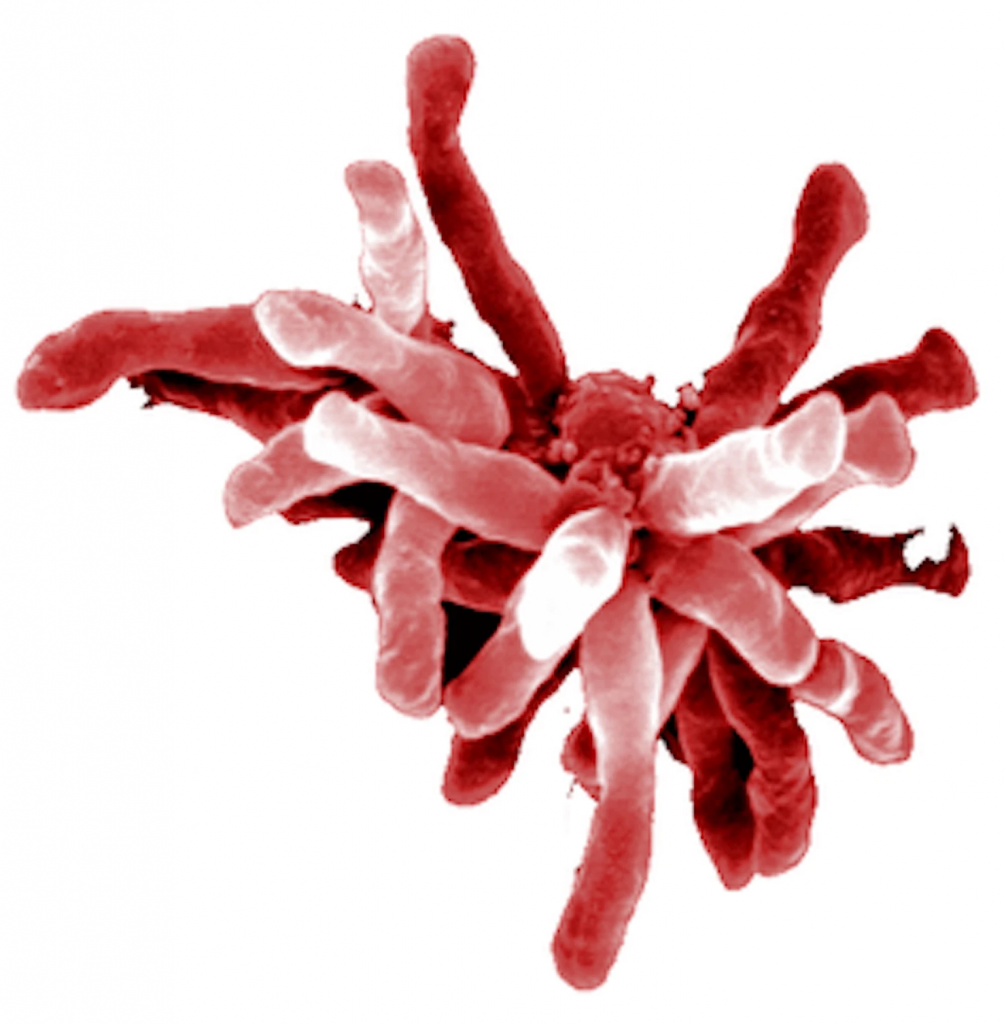

- Rhodopseudomonas palustris

That all being said, the biggest benefit in my mind, which is what made me really look at them in the first place, is their impressive nutritional content. Their protein content, for example, can be over 70%. They contain vitamins, including vitamin E and most of the B vitamin complex (or all of the complex in certain mixed-species formulae). They also are capable of synthesizing their own omega-6 fatty acids such as ARA from crude organic wastes (e.g., aquarium detritus). And most notably, they’re an awesome source of carotenoid pigments such as lycopene and astaxanthin. Aquarists are most familiar with carotenoids as color enhancers, but they play far important roles than that. For one, they enhance the immune system. And, they act as powerful antioxidants, scavenging oxygen and peroxyl radicals (such as the photo oxidants generated by the photosynthetic activity of Symbiodiniaceae in scleractinian corals) that damage tissue and accelerate the aging process.

As studies show, purple phototrophic bacteria are very prominently represented in healthy natural reef microbiomes. PNSB such as Rhodopseudomonas are frequently found among the microbiomes of wild corals. It’s widely believed that they play a role in sulfur cycling within the coral holobiont. In one study, Rhodopseudomonas accounted for around a fourth of all the bacterial genera encoding sulfur oxidation genes in the surface mucus layer of outer-reef (i.e., more stable environment) corals, while Rhodopseudomonas, Ruegeria, and Roseobacter more equally accounted for that of inner-reef (i.e., more environmental fluctuation) corals.

But when it comes to mutualism with corals, PNSB seem to be most important as nitrogen fixers (also known as diazotrophs). Nitrogen fixation is essentially the opposite of denitrification, whereby nitrogen gas is converted into a biologically available nitrogenous compound (i.e., ammonia). This is often a vital source of ammonia for Symbiodiniaceae, as coral reefs tend to be nitrogen-limited ecosystems (zooxanthellae utilize ammonia, not nitrate, as a nitrogen source). Until the real scope of the influence of diazotrophic reef bacteria was truly understood, it was a mystery to biologists how corals could be so damned productive in such an infertile environment; it turns out that this arrangement is a sweetheart deal for corals, as the ammonia is more efficiently appropriated to the Symbiodiniaceae, while also allowing corals to hoard the ammonia away from their mortal enemy, benthic algae.

Interestingly, the abundance of PNSB and other nitrogen fixers appears to change along with flux of nitrogen availability, which changes with the seasons. In one study of Galaxia and Porites corals, the relative abundance of endosymbiotic Rhodopseudomonas palustris was greater in the spring and summer months when nitrogen starvation is greatest. In fact, Rhodopseudomonas palustris was found to dominate diazotrophic assemblages in summer Porites samples, as well as that of all spring Galaxia and Porites colonies sampled. Definitely something to turn your head to!

So, why would any of this be interesting to the average reef aquarist?

Nutrition is a major factor in any coral’s health. And while the photosynthates (primarily carbs) produced by zooxanthellae provide a critical source of energy, they are not by themselves nutritionally adequate. Yes, consumption of the zooxanthellae themselves can provide the coral with a source of protein, fatty acids, and so on. But the coral would be unable to meet its need for nutritional nitrogen (e.g., protein) by feeding exclusively on zooxanthellae, given the latter’s inability to fix nitrogen and the typically oligotrophic condition of reef habitats. This is why corals eat stuff from the planktos. And their primary non-zooxanthellate food source in the wild? According to the most recent science: bacterioplankton.

Now, we obviously have bacteria in our tanks, and the corals likely can eat them (or some of them anyway). Also, there are all kinds of cheaper and more convenient foods we could use. Fair enough. But our tanks have been shown to lack in the densities/types of bacterioplankton required to match a coral’s normal dietary intake. So the practice of feeding captive corals this natural planktonic food source, bacteria in general, and PNSB specifically, has some merit. For one, let’s listen to the corals. Though the mechanism of selectivity is not well understood at this time, it appears that corals are picky about what they eat and are capable of ingesting certain preferred microbes while rejecting other, less favored, ones. One study illustrates how Porites not only feeds on, but seemingly attracts, certain types of bacteria with a preference for Rhodobacteraceae, which include the ecologically heavy-hitting purple bacterial genera Rhodobacter and Roseobacter. Similarly, corals utilize some unknown means of selecting beneficial microbial genera from the plankton, and even farming them endogenously, for use as endosymbionts.

Why? Why have corals evolved to be so finicky?

Because not all bacteria are equally beneficial. Some are downright harmful. It definitely seems feasible that a coral’s affinity for Rhodopseudomonas might be threefold: (1) For the microbe’s excellent nutritional content, including its rich content of protein and oxidant-busting carotenoids, (2) its ability to provide a continuous supply of ammonia directly to the Symbiodiniaceae, and (3) its oft-observed ability to inhibit potentially deadly pathogens such as Vibrio.

That’s not to say that PNSB are perfect, or even complete, as a food. For example, one study determined that while Rhodopseudomonas has an overall great nutritional profile, it lacks in certain essential fatty acids. Another study found them nutritionally comparable to spirulina, which is generally regarded as wholesome; in this case, using zas a model organism, PNSB didn’t perform exceptionally in terms of promoting high growth rate, but was shown to contain ample amounts of the amino acids methionine and phenylalaninea (both of which tend to be deficient in typical aquaculture feeds). Given this, and its high protein content, but also its insufficient content of certain fats/fatty acids, the authors conclude that PNSB are better used to compliment, rather than replace, high-fat/low-protein items such as phytoplankton and zooxanthellae. For this reason we suggest pairing PNSB with an alga that has a desirable fatty acid composition (e.g., Isochrysis); such a combination is nutritionally superior to either food item by itself.

So there you go! All things considered, I believe that PNSB are an acceptable, if not excellent, choice of food for corals, even among live foods. The other perks–consumption of organic wastes, denitrification, and so on–I consider to be mere icing on the cake. That’s not to say that the bioremediation capabilities of these microbes aren’t significant; rather, because the extent to which these bacteria improve water quality varies from tank to tank (every tank is ecologically unique), I prefer to focus on nutrition and consider it sufficient that instead of fouling the water, this food actually cleans the water to some extent. Yes, I’ve written a lot about how these microbes carry out processes like denitrification, phosphate accumulation, DMSP degradation, etc., but that’s simply because the aquarium community remains interested in that stuff (and I agree that it’s pretty interesting). That notwithstanding, I consider my job to be the same one I’ve had for over two decades now: culturing live aquacultural microfeed.

Can PNS probiotics be used in freshwater tanks or are they marine specific?

They absolutely can, and are. Rhodopseudomonas, for example, has been used successfully in ponds to break down organic wastes including leaf litter (leaves and other plant matter are rich in cellulose, which few microbes possess the enzymes to degrade). This ability, along with their habit of secreting plant growth hormones such as auxins, makes them an excellent choice for a freshwater planted aquarium. Oh, that and of course their activity as nitrogen fixers–this is why PNSB are an important component of horticultural microbial consortia such as the famous Effective Microorganisms (EM) formulae.

It terms of being used as a probiotic fish food additive, they may be used safely for either fresh or saltwater species with equal effect (increased feed conversion, reduced food waste, and stimulated immunoresponse).

What is PNS YelloSno™?

PNS YelloSno™ was designed to compliment our live products. It is essentially a marine snow simulation. In the short-story version, marine snow arises from the agglomeration of small particles into larger particles due to the stickiness of the biofilm produced by microbes growing on the particles, if that makes sense. We were excited to learn early on that purple bacteria are often associated with marine snow. Thus, we developed PNS YelloSno™ as a way to deliver the nutrition from PNSB to those filter-feeders that tend to capture particle sizes larger than the very teeny single-cell size (only a couple microns).

While it’s made with live bacteria (Rhodopseudomonas palustris), PNS YelloSno™ is flash pasteurized to maintain shelf stability. In other words, it’s not a live product (and requires refrigeration). As such (being produced by live microbes), it has a ‘taste’ and ‘feel’ that is as naturally familiar as marine snow to suspension-feeding invertebrates. This is crucial, because some animals are so thoroughly evolved to consume this resource and are highly selective for it (for example, some gorgonians actually reject phytoplankton in favor of marine snow!). In addition to the nutrition of the bacterial biomass (including the polysaccharide-rich biofilms the bacteria produce), PNS YelloSno™ is rich in bioavailable trace elements, minerals, and vitamins (including the entire B vitamin complex).

We’re hardly the only ones that have produced and used live PNSB for these purposes; people have been doing that since the 70s, and maybe even for longer in SE Asia. But to my knowledge, no one has yet developed a product like PNS YelloSno™. So that’s definitely the product we’re most proud of, and I still get stoked hearing back from users who tell me their corals love the stuff.

In your opinion, why is understanding microbes and developing probiotic products essential for advancing the aquarium industry?

For me, as an ecologist, that’s pretty simple: Microorganisms are the foundation of every ecosystem. The microbiome doesn’t merely affect the greater biological community, it completely sets the course of its very development. Sure, we can have an aquarium with, say, an apparently healthy fish or plant or coral alongside a microbiome that does not closely resemble that of the plant’s/animal’s healthy natural habitat. In such a case, however, we must very frequently take corrective measures to counter the resulting imbalances of nutrient concentration, populations of pathogenic microbes, and so on.

To be clear, I don’t see microbial products as magical potions that altogether eliminate the need for water changes or good husbandry in general. But I would say that there’s ample scientific and anecdotal evidence to suggest–strongly, in my opinion–that a ‘healthy’ and ‘complete’ microbiome can significantly reduce the need for things like chemical filtrants, algicides, antibiotics, and so on. And yes, in some cases, even reduce the need for water changes. In the reef aquarium industry specifically, I think the most potential for microbial products lies in the field of coral nutrition (bacterioplankton are a coral’s primary exogenous food source, after all).

Do your products have applications in commercial agriculture/aquaculture? Do you consider your products to be ‘sustainable’?

Our products have been used, thus far, mostly in the aquarium industry. However, PNSB (especially Rhodopseudomonas) are already used extensively in both agriculture and aquaculture. For example, I believe the PGA golf courses are treated with PNSB. They’re proven to be effective as probiotics for all sorts of aquaculture, and are today heavily relied upon by shrimp farmers. They’ve even been shown to increase meat weight and meat quality in broiler chickens when added to the drinking water. Have they appeared in human probiotic formulae, too? Yep, but please do not drink your PNS ProBio™ haha (seriously)! Right now, one of the largest cannabis farms in California is testing one of our trial formulations for its efficacy as a horticultural inoculant. Lots of potential uses! And none of this is witchcraft, but rather is supported by heaps of research (yes, see for yourself, you’ll be absolutely amazed!).

Yes, they’re sustainable in the sense that they can lessen the negative impact of human industry on our natural environment. Here are a few examples. The big one is their use as nitrogen fixers and phosphate accumulators–because cash crops rely less on synthetic fertilizer when treated with PNSB, there’s less agricultural runoff going into our streams, rivers, and oceans. Another example is their activity as probiotics (e.g., preventing vibriosis in farmed shrimp); PNSB may reduce the use of antibiotics, which is increasingly becoming problematic in agriculture. Maybe my favorite example here is still a hypothetical one, but I’m fascinated with studies demonstrating how they can be grown on agricultural waste products (stevia wastewater, olive pressings, etc.) and then used (for their high protein/amino acid content) as an animal feed supplement. Cool stuff!

What is your idea of the ideal aquarium?

I like to say to that there are two major types of aquaria: Naturalistic systems, and greenhouse-ified systems. To me, a system is naturalistic to the extent that it resembles natural ecological processes. So, nutrient cycling is primarily microbiologically driven, herbivores are responsible for most if not all algae control, lots of the animals’ food sources are produced in situ, etc. As I see it, these systems are operated on a “let God sort them out” kind of wholistic approach where only the fit survive; the system isn’t tweaked in any major way to suit a single species.

The greenhouse-ified approach favors, and indeed pampers, selected organisms. We see an extreme example of this in a commercial aquaculture facility, or even a basement frag grow-out system–barebottom, no aquascape to speak of, lower diversity, highly focused care on select species, and above all a very large reliance on technology/intensive husbandry. As in a greenhouse, this setting is not necessarily designed to mimic a natural habitat, but rather to maximize the survival/growth of a limited number of target species.

As anyone who knows me well might easily guess, my ideal aquarium is more representative of the naturalistic school. I tend to look up to figures like Lee Chin Eng and Dr. Walter Adey. I haven’t even used filters (just pumps) in most of my freshwater and saltwater systems for some time now.

Still, as someone who’s toiled in the production setting for 25,000+ hours throughout my career as a process biologist, I understand that there’s a time and place for everything. The naturalistic approach has its limits, as does a heavy reliance on technology. With that, I’ll conclude by pointing out that all of our systems are some combination of both approaches. What I love about these bacteria is that they they straddle both worlds. Though I first ‘discovered’ PNSB while looking for ways to shave operational costs and improve nutrition in a decidedly production-oriented environment at AlgaeBarn, they’ve proven to be extremely valuable to me for building what I consider to be reasonably naturalistic systems. That, and tomatoes; since finding one particularly intriguing paper, I’ve grown the biggest and reddest tomatoes I’ve ever seen in my life haha. So maybe PNSB are helping me to build my ideal garden as well, ha.

But I digress. I don’t really know if there’s one ideal tank out there, but as far as marine tanks go, I’d consider any system containing healthy, growing Dendronephthya a notable achievement. I’ve tried them in the past with some limited success, but intend to improve my NPS coral tank game and eventually give that type of coral another try soon. Specifically, I want to see if I can fulfill its dietary requirements, at least in part, with PNSB. And we shall see! Ha, right now I’m busy enough just trying to get our new facility back up and fully operational. But as all of us hobbyists know, it’s the view over the horizon, new things to try, that keeps us engaged and keeps things fun. Right?

Thanks for all of your great questions, and happy reefing!

0 Comments