Every aquarist, no matter their experience level, will eventually have questions regarding some problem they are facing with their aquarium. Getting an appropriate answer to these questions is vitally important; the lives of the animals in your care depend on it. Receiving incorrect information and then acting on it (as you may not know any different) can be more detrimental for your animals than taking no action at all. The following is an overview of the typical informational resources available to home aquarists, along with some benefits and potential drawbacks of each:

Books – Prior to the advent of the Internet, print books were one of the primary informational resources for home aquarists. Because of the competitive nature of getting a book published, combined with (usually) extensive editorial oversight, books generally contain accurate information. Of course, some are better than others, but because it is so costly to produce a print run of books, few publishers wish to risk being stuck with a “dog”, so they keep close reins on their authors. Beware of “self-published” titles – these are always written by people who have first tried to interest a mainstream publisher in their book, but failed. This means that the publishers did not feel the quality was up to their standards, or that the book lacked sufficient marketability.

Most professional aquarists with information that they want to share with the greatest number of other people still choose books as their primary venue. There is something about the permanence of a book that holds great appeal for most authors.

Electronic magazines – Internet magazines have become a boon for aquarists. Usually having free access, the fast publication schedule of these “e-zines” means that aquarists can have access to the freshest information possible. Along with that rapid publication speed does come some increased potential for errors or omissions – but by virtue of the material being online; corrections take only seconds to perform. There is also a tendency for online magazines to be able to avoid some of the pitfalls of print media – since web hosting space is so inexpensive, there are fewer problems with article length, number of photographs, etc., that plague print magazines. Too often, an article for a print magazine is called for like this: “We need 2400 words on dottybacks with six images and two sidebars.” This results in the author changing the article to fit the publisher’s needs – perhaps for the worse, especially if they had originally wanted to write 3500 words, and had 20

images to go with it!

Fellow club members – People who join their local aquarium club have a ready source of information in talking with other members. The primary benefit of this is that fellow members will have good knowledge of the local aquarium business scene – which stores are good, which ones are a bit less so. Also, since most of the interaction takes place face-to-face, there is less chance of ambiguity ruining the advice given. Finally, since the advice flow is so personal, people take great pains to be as accurate as possible, as any bad advice given may well come back to haunt them at the next club meeting. Some drawbacks include the fact that many members are on the same level in terms of hobby experience, so the really tough questions may go unanswered. Some clubs are subsidized by local pet stores, so there may be a commercial slant to overcome. Finally, it seems that many hobby clubs suffer from internal political problems – one faction trying to take control, or certain

people being ostracized, etc.

Extrapolation from other sources – Except for public aquariums, the aquarium hobby (and its information sources) are mostly non-professional. This leads some aquarists to seek out professional information from related fields such as veterinary or human medicine, marine biology or chemistry. While this professional information (that was usually peer-reviewed) is precise in its own context, its application when extrapolated to home aquariums may not always give suitable results. One example was a paper from Varner and Lewis in 1991 that associated a virus with cases of Head and Lateral Line Erosion (HLLE) in Pomacanthus sp. angelfish. This caused many home aquarists to believe that HLLE is a communicable disease, as most viral infections are. The problem is that subsequent studies have created doubt surrounding the virus actually being the cause of HLLE, and nobody has every demonstrated transfer of HLLE from one fish to another in a manner that suggests

that it is a contagious disease.

Internet forums – This form of information exchange is by far the most commonly used at the present time. Since the member base of most of these groups is huge, there is a wealth of information to draw from. Many forums are very active, meaning that answers to questions may be posted within minutes or hours. However, aquarists need to plan their information requests somewhat; posting an emergency question at 2 a.m. on a Monday morning will probably not result in a proper response within a hoped-for 30 minute time frame.

There has also been the creation of what is termed “Niche Experts” – people on a particular forum, (or section of a forum) that have become the local expert on certain topics. Utilizing them for information works well as long as these people supplying the information are truly experts in their fields and not that they just know “just a bit more” than the people they are responding to. Another problem is when these niche experts then begin to expound on other topics that they are not quite as familiar with. Their status as an expert belies the fact that they do not have as strong of a knowledge base on other topics that they might branch out into.

Manufacturers – Manufacturers should be responsible for supplying technical information about the products they produce. Some forward-thinking manufacturers have produced their own newsletters or even short magazines that provide general information about the aquarium hobby. Of course, everyone understands that their primary business is to sell product, so it is expected that the information that they provide would support that goal in some way. There is not anything inherently wrong with this combination of business and information flow – as long as it is kept to reasonable levels.

Print magazines – Print magazines are positioned between books and Internet resources in terms of timeliness of their information. In regards to accuracy, most articles are reviewed by editors who are familiar with aquariums, so most errors are corrected before they reach print. It is suspected that some magazines must kowtow to manufacturers who advertise with them; to the degree that they do not allow certain topics to be covered that might negatively impact the sales for those manufacturers. The most common example of this is a distinct lack of comprehensive product reviews in most magazines. With the advent of the Internet, there seems to have been a corresponding general decline in print magazine sales. While most of these magazines have remained in operations for many years, overall subscription rates seem to be gradually declining. One magazine had seen monthly distribution of 50,000 copies 30 years ago, and this has decreased to around 20,000 copies a month

today.

Personal research – Simply put, this information resource is when the aquarist cannot find an answer for a problem, and researches the issue for themselves. For example, I once needed to calculate a very critical dosage for a medication. I needed to know the exact volume of water contained in the aquarium, including the amount found in the interstices of the gravel – and add that into the calculation. During one lunch hour, I had run a series of tests using gravel and graduated cylinders, I soon discovered that about 30% of a layer of regular sized aquarium gravel is actually water, and was able to factor that in to my dosage calculation. Of course, this only works well for simple, narrowly focused questions such as this. Problems such as “all my fish just died, why?” do not lend themselves well to this particular technique.

A simple experiment to measure of the volume of water held in the interstices of gravel showed that about one third of the volume of a gravel bed is actually water.

Pet store employees – Often, the frontline informational resource for beginning aquarists is the pet store employee. These store workers need to be able to respond daily to inquiries such as, “what filter should I buy?”, and “will these fish be compatible with those that I already have?” Since you are their customer, they have a vested interest in your success. However, not all store employees are up to this challenge, so if you find a knowledgeable one, learn their work schedule and preferentially shop with them. Similar to aquarium clubs, since the information exchange is usually face-to-face, the person dispensing the advice has a personal interest in trying to give you the most accurate answer possible – to avoid having the problem come back to them should the advice fail.

Web pages – The Internet has substantially changed how home aquarists gather, process and implement information about their aquariums. “Googling” has become a verb. This is the resource that I generally use myself. Web searches will result in a wide variety of information, from technical papers, to online aquarium magazines to threads on Internet forums. I feel that I have enough experience to separate the “chaff from the seed” and can quickly discount any erroneous information that may show up in the search engine results. Because the search engines work best when fed just a single word or a term, they are not well-suited for broad questions such as “how many fish can I safely add to my 20 gallon aquarium?”

The Internet is a special case. I was very active on CompuServe’s FISHNET forums back in the 1980’s, but had not been very active on the newer web based forums until recently. I’ve noticed a disturbing trend where certain bad ideas taken hold on certain forums, and people have gotten lax in the answers. In particular, the fish disease forums are rife with poor advice. This article actually began life as a rebuttal to a self-proclaimed niche-expert who was dispensing horribly bad advice on fish disease treatments. I tried a posting polite correction and when that went unheeded, I was a bit more assertive; but all I received as a result was a scathing IM from the person. The following is a compilation of some of the problems with information quality that I’ve seen in various aquarium forums over the past few years. The wording of these may not always be exactly the same, but the general ideas keep resurfacing:

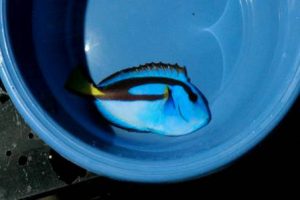

1. “I drip-acclimated my fish for XX hours just like I was told.” XX can be anything from four to eight hours, sometimes more. There are only two specialized instances where acclimation times this lengthy are justified: when moving a fish from lower specific gravity to a tank that is much higher and in cases where the shipment time was in excess of 36 hours. In both of these instances, life support is maintained by aeration and keeping the temperature within range. In the case of lengthy shipments, the pH / ammonia issue must be dealt with.

Think about this – you have been outside without a coat, you are hypothermic, you are then given the choice of going inside and sitting by a space heater or moving into the garage to warm up just a little, and then an hour later, go into the house – your choice is? It is the same with fish and inverts – any temperature acclimation times of more than 15 minutes are useless. Temperature shock is a much rarer thing than you might think – many more fish die due to low dissolved oxygen or high ammonia while being acclimated too long for temperature (Hemdal 2006). Perhaps worry about photo-shock, pH change and specific gravity increases, but don’t go overboard. Ultimately, ask yourself; what is more stressful to a fish – acclimating them in a bare Styrofoam box or bucket for five hours, or having the water parameters abruptly change, but then being able to hole up undercover in a dark cave inside a good quality aquarium to recuperate?

2. Hyposalinity treatments are “a soothing tonic” for marine fish and need to be run at a specific gravity of 1.009 for six weeks. No: This treatment is stressful, as evidenced by the number of Uronema protozoan outbreaks I’ve seen when people try this. In my opinion, although many fish can tolerate 1.009, there is no reason to go below 1.0125 – this is the original treatment refined by public aquariums about 30 years ago.

This green chromis died from an infection of the protozoan Uronema, yet based on its gross visual symptoms, most people would have suspected a bacterial infection.

3. Question, “My fish has cloudy eyes, what should I do?” Too many times people post their overly concise answer as “Move to a quarantine tank and treat with antibiotics”.

Flukes can cause cloudy eyes, injuries cause cloudy eyes, fish can develop cataracts. Nobody can diagnose bacterial diseases based on simple written symptoms! You need to ask follow up questions and offer some alternatives.

4. “Give your fish a 30 minute freshwater dip”. There is no justification for performing a freshwater dip longer than 7 minutes, and five is usually tolerated much better. I am amazed to hear a pundit explain how to carefully adjust the temperature and pH of the dip water to that of the tank (to avoid stressing the fish) and then tell the same person to dip the fish for 30 minutes in freshwater….no THAT isn’t stressful.

5. One sentence answers to just about ANY fish disease question. Does anyone really think that people have the magical ability to diagnose and treat fish disease problems in 10 words or less without at least some follow up questions?

6. Don’t give out human medical advice unless you are a physician. Don’t give your opinion on things like “Help, I was stung/bitten by my fish”, or “I inhaled/swallowed this chemical, what should I do?” Don’t give out structural engineering advice unless you are an expert. There is a reason why these people need to be licensed. If you do decide to dispense professional advice without actually being a professional, at least add sufficient disclaimers to your post.

7. Any problem solution that has as its main advice, “Feed vitamin C and/or garlic”. There needs to be some references here that are not purely anecdotal. If you prescribe a medication that starts with the word “super” or “magical” ends with “- fixit” or “- cure-all” think twice – and then at least tell the person what the active ingredient is. Wait, they don’t list the ingredients on the label? Hmmm, now that might be a problem……

Now – the people posting responses to problems are not the only issue; the person who initiates the thread has some responsibility:

8. Don’t post ambiguous, short messages about a fish problem with no pictures and expect to get any meaningful advice.

9. Go ahead and ignore replying posts that give advice you don’t want to follow, can’t afford or don’t want to accept, but be prepared for possible continuing problems.

10. Don’t wait too long before posting. Problem reports that begin with “I lost three fish today, two yesterday and one the day before that….” are probably not going to end well for the rest of the fish (no matter what advice you are given) now that its day four.

11. Check the answers you get from strangers on the Internet with information from published sources. “Fish Doctorz” advice may sound really good, but he could be some junior high kid with his first tank just “chillaxin” and tossing out random bits of information on the forum because it makes him feel important.

12. Check the FAQ! You most likely are not the first, (or even the fiftieth) person to post a question about HLLE – research the forum before posting commonly asked questions.

As a pet store department manager in the early 1980’s to working as a public aquarium curator at the present time, I’ve fielded tens of thousands of questions from hobbyists about their aquariums. The questions have run the gamut of dealing with new tank syndrome in a goldfish bowl to advice on how to build a 2500 gallon shark tank.

I use a series of informal rules whenever I attempt to answer questions from aquarists, these same rules may help others dispense better advice as well:

- If I don’t have adequate first hand knowledge about the animal in question, I tell the person I cannot help them. Too many “experts” feel strangely compelled to give answers about something they have no direct knowledge of.

- Always ask enough questions and gather enough background information, (through water tests, etc.) so that a reasonable solution (or range of solutions) to the problem can be given.

- The most common problem is usually the correct diagnosis; a newly established tank is probably suffering from ammonia poisoning and not a result of toxic water from some unknown chemical reaction.

- When answering a question about a fish that you have not seen firsthand, never give your answer in absolutes, rather say; “your fish may have Cryptocaryon” instead of “your fish have Cryptocaryon“. This gives the person pause for thought, and they are more likely to double check your answer.

Always conclude your advice with a strong caveat that the person should seek a second opinion, and that because you cannot actually see the animal, you have to formulate a solution based solely on the information they provided.

One final note on misinformation – it seems that chronic problems with aquariums are the issues where the most misinformation abounds. Head and Lateral Line Erosion, Aiptasia anemone removal, Lymphocystis, what size of a tank does a fish need, are all issues where not only is there a lot of room for different opinions, but there is TIME for the aquarist to seek out information from a variety of sources.

In some cases, people tend to blame others for their animal losses: “I bought this fish and it got sick, and the store told me to treat it with this product, but it died” does not mean that the store was at fault. It was your fish, under your care when it died. Ultimately, I think that all aquarists need to understand this, and I feel they know that deep down; they are completely responsible for gathering and then applying appropriate information in order to care for their aquariums in the best possible manner. Just the fact that you are given bad or incomplete advice does not mean that you have to use it, check and re-check your information so that your aquariums are cared for properly.

Bibliography

- Hemdal, J.F. 2006. Advanced Marine Aquarium Techniques. 352pp. TFH publications, neptune City, New Jersey

- Hemdal, J.F. 2003. Head and lateral line erosion. Aquarium Fish 15(4):28-35

- Hemdal, J.F. 2000. Aquarium problem solving. Freshwater and Marine Aquarium

- 23(5):108-118

- Varner, P.W. and Lewis, D.H. 1991. Characterization of a Virus Associated with Head and Lateral Line Erosion Syndrome in Marine Angelfish. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health 3:198-205

0 Comments