For most, the term coral reef invokes-rather understandably-images of scleractinian (or, reef building) corals. While there is a bewildering diversity of color and form among scleractinian coral species, the group is almost exclusively zooxanthellate (i.e., photosynthetic) and epifaunal (i.e., hard-bottom dwelling). Indeed, infaunal (i.e., soft-bottom dwelling), azooxanthellate (i.e., nonphotosynthetic) species are fairly unusual among corals in particular and among cnidarians in general.

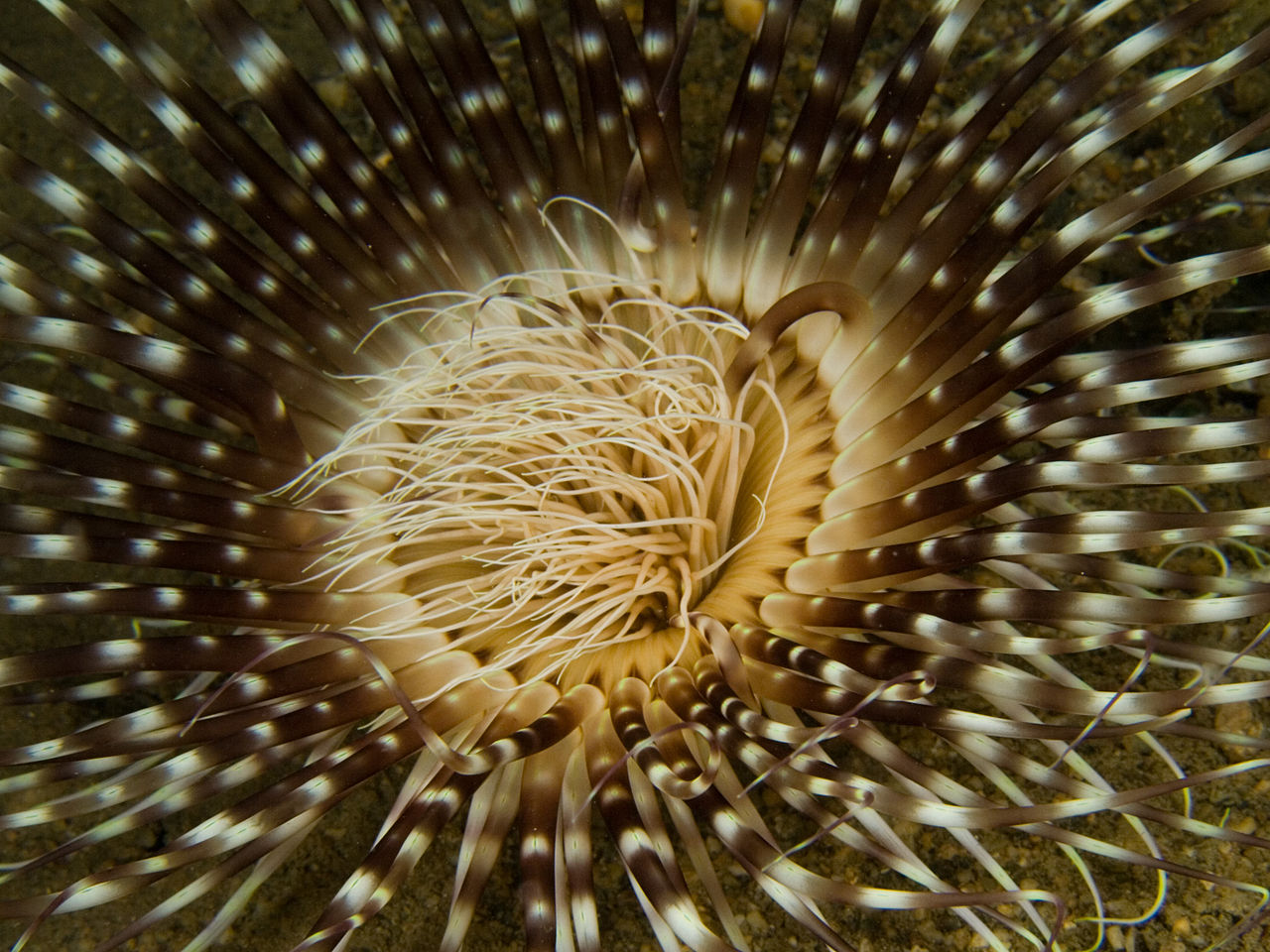

Cerianthids are characterized by having two distinct types of tentacles. Photo by Jimmy Hoehlein (image reproduced with permission of copyright holder House of Fins).

Aquarists are oftentimes attracted to the unusual. For sure, infaunal, nonphotosynthetic (NPS) cnidarians are underrepresented in the aquarium trade, not because they lack potential as interesting aquarium animals, but rather because of their poor record of survivability in “mixed reef” systems. That being said, these atypical species can adapt well to marine aquaria when kept under appropriate conditions; NPS biotopes with deep sand beds or deep mud beds are especially suitable for this purpose. This piece presents an overview of one such group of animals, the Ceriantharia (or, the tube anemones).

Tube anemones are solitary Hexacorallia belonging to the order Ceriantharia. The order is comprised of only 25 species or so in three families. While cerianthids bear a strong resemblance to the better-known “true” sea anemones (Order Actinaria), they belong to an entirely different subclass of anthozoans (i.e., Ceriantipatharia, which traditionally also includes the black corals).

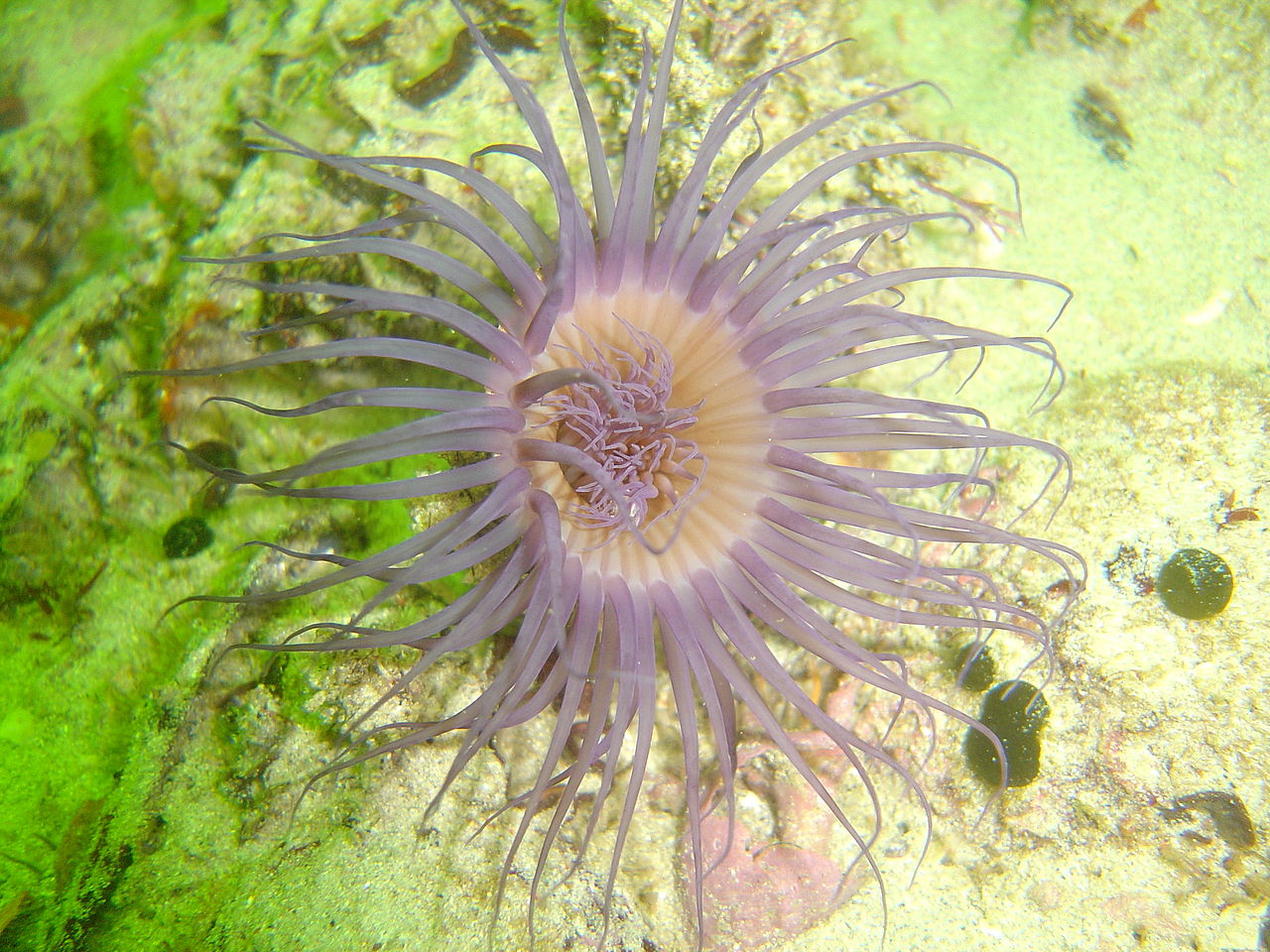

Tube-dwelling anemones can be found in the sandy shallows of inner coral reefs, in the vicinity of sea grass beds or in very deep mud flats. Andre Piazza (Wikimedia Commons), CC-By-SA.

Cerianthids most conspicuously differ from sea anemones by the lack of a pedal disc. The column in adults is rounded at the aboral end, elongated and highly contractile. Contraction is carried out by a layer of strong, ectodermal longitudinal muscles in the column wall. Sphincter muscles are absent. Longitudinal muscles are absent or poorly developed on the mesenteries. Certain structures may be present on the mesenteries, including filamentous organs resembling acontia (or, acontioids), rounded extensions bearing nematocysts (or, cnidorhagae), bunches of cnidorhagae on stalks (or, botrucnids) and outgrowths of the mesenterial lamella supporting sections of mesenteric filaments (or, craspedonemes). Cerianthids generally have a single, dorsal siphonoglyph. In some genera, the siphonoglyph forms a groove (or, hyposulcus) that connects the directive mesenteries; an extension of the groove (or, hemisulcus) may continue below separately on each directive mesentery (den Hartog 1977).

Temperate cerianthids will appreciate a drop in temperature (less than 68ºF) for several months each winter. Photo: Peter Southwood (Wikimedia Commons), CC-By-SA.

A tentacular crown is situated at the top of the column. Tube anemones are distinguished by having two distinct whorls of tentacles. Each whorl consists of a different type of tentacle. The outer (or, marginal) whorl consists of very long, fine, flowing, tapered tentacles at the periphery of the disc that are primarily used for defense and food capture; the inner (or, labial) whorl consists of rather short, erect tentacles at the entrance to the actinopharynx that are primarily used to manipulate and ingest food items. In some species, certain areas of the tentacles may be bioluminescent. The tentacles cannot be retracted into the column. Because the mesenteries are unpaired, the whorls are arranged in pseudocycles (rather than true cycles); one marginal and one labial tentacle is associated with each lateral mesenteric chamber (den Hartog 1977).

As adults, cerianthids dwell in a long, soft tube. The tube is constructed from specialized cnidae threads (or, ptychocysts) and mucus, though it may incorporate other materials such as sand. The outside texture of the tube is much like slimy, wet shreds of paper; the inside texture is rather slick and smooth. The tube is typically buried in mud, sand or gravel, though it may be wedged into or between rocks. It may be much greater in length than the anemone itself (>2.0 m long). The tentacular crown emerges from the distal end of the tube; however, if it is threatened, the animal can very quickly retreat beneath the substrate into the bottom of the tube.

Oftentimes, different color forms of certain cerianthid species can be mixed for stunning visual effect. Photo by Kenneth Wingerter.

Tube anemones are distributed widely across tropical and temperate oceans. Cerianthus spp. is found in the Mediterranean, Pachycerianthus spp. is found in the Indo-Pacific and Arachnantus spp. is found in the Caribbean. They do not occur directly on coral reefs; they are instead found on soft, muddy sand bottoms, often between reef structures. They generally inhabit areas of moderate flow in deeper waters, where they are less likely to be uprooted by turbulence. While they are primarily sessile, they can extract themselves from the sea bottom and relocate by passively drifting to and re-anchoring in a more suitable site when necessary. They are most successful where there is an abundance of food items such as zooplankton, detritus and “marine snow.”

The marginal tentacles of cerianthids are frequently adorned with attractive spots and stripes. Nick Hobgood (Wikimedia Commons), CC-By-SA.

Mediterranean and North Sea tube anemones have been collected for European marine aquarists for many years. North American hobbyists are most familiar with the larger tropical species. At present, Cerianthus membranaceus is the most commonly offered tube anemone species in the trade.

Tube anemones may arrive at the retailer in a compromised condition due to improper handling and transport. Prospective buyers should be wary of any specimen that has abandoned its tube and is lying on the surface of the substrate. When disturbed, a healthy individual will exhibit a cough reaction, forcefully ejecting water from its terminal vacuole.

A newly purchased tube anemone should be carefully acclimated before introducing it to a new aquarium. It is best to rinse the animal of any loose pieces of tube and other debris before placement. The animal may be buried in the substrate to just below the top of the tube. If the animal evacuates its tube, do not attempt to force it back in or rebury it; instead, leave it alone, as it will most likely rebury itself in a location of its own choosing and construct an entirely new tube.

Nocturnal cerianthids can be trained to feed during light hours in captivity. Photo by Kenneth Wingerter.

Most authors agree that cerianthids are quite easy to care for. They are all azooxanthellate, though many are nevertheless unaffected by intense illumination. Tube anemones easily adapt to chaotic water flow. However, they might benefit most from alternating laminar flows that simulate ingoing/outgoing tidal currents. Though tube anemones prefer robust water movement, strong currents should not flow directly onto the animal. Flow rates should be just high enough to deliver maximal amounts of food and oxygen to the animal without disrupting full extension of the tentacles. Periodic, intermittent currents are said to be ideal. Pump timers may be used to create these conditions; fine tuning of both flow velocity and flow dynamics can elicit the proper expansion and feeding behavior of this animal.

Tube anemones should be provided with the deepest and finest (<4.0 mm grain diameter) substrate possible. A silty sand such as Miracle Mud® is usually suitable. The best placement for a tube anemone is in an open area where it can fully expand without coming into contact with its neighbors.

A beautiful example of a golden tube-dwelling anemone (Cerianthus filiformis) at Suma Aqualife Park, Kobe, Japan. Photo: Mutsu-sango (Wikimedia Commons), CC-By-SA .

Tube anemones will sting any animal that touches their tentacles. However, it should be noted that the potency of their sting is not nearly as great as some authors have previously suggested (Toonen 2004). In actual fact, they are no more dangerous to their tankmates than most common sea anemone species. One study demonstrated that out of eleven cnidarian species (including true sea anemones as well as corallimorpharians), the stinging cells of tube anemones were deemed the least toxic (Cline & Wolowyk 1997). Another study (Phelan & Blanquet 1985) found that the stinging cells produced by Pachycerianthus torryi are significantly less toxic than those of Aiptasia pallida.

Tube anemones can be fed a variety of foods ranging from pulverized flake food to zooplankton (Mysis, Artemia, etc.) or finely chopped meaty foods. Though they appear to be capable of capturing large items (e.g., whole silversides), such foods should be avoided as they can damage the animal’s delicate tentacles and are not as easily managed by its digestive system. Light, frequent feedings are better than heavy, sporadic feedings. In most cases, one daily spot feeding should suffice.

Properly cared for, tube anemones are exceptionally long-lasting aquarium animals. Some specimens are said to have survived for over 100 years in captivity. To date, there are few (if any) credible records of the captive reproduction of a cerianthid species. However, the successful captive rearing of Cerianthus lloydii larvae captured in plankton is certainly encouraging. With ongoing improvements in harvest, shipping, feeding and propagation methods, the presence and popularity of these unique creatures is almost sure to grow among serious aquarium hobbyists.

Cerianthus membranaceus is widely available to aquarists. Photo: Dawson (Wikimedia Commons), CC-By-SA.

References

- Cline EI, Wolowyk MW. (1997). Cardiac stimulatory, cytotoxic and cytolytic activity of extracts of sea anemones. International Journal of Pharmacognosy 35:91-98.

- den Hartog, J.C. (1977). Descriptions of two new Ceriantharia from the Caribbean region, Pachycerianthus curacueensis n. sp. and Arachnanthus nocturnus n. sp. with a discussion of the cnidom and of the classification of the Ceriantharia. Zool. Meded., Leiden 51 (14): 211-242.

- Phelan MA, Blanquet RS. (1985). Characterization of nematocyst proteins from the sea anemones Aiptasia pallida and Pachycerianthus torreyi (Cnidaria, Anthozoa). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology B-Biochemistry & Molecular Biology 81:661-666.

- Toonen, Robert. (2004). Aquarium Invertebrates: Tube Anemones. http://www.advancedaquarist.com/2004/6/inverts.

An image of a banded tube anemone captured at night. Photo: Nick Hobgood (Wikimedia Commons), CC-By-SA.

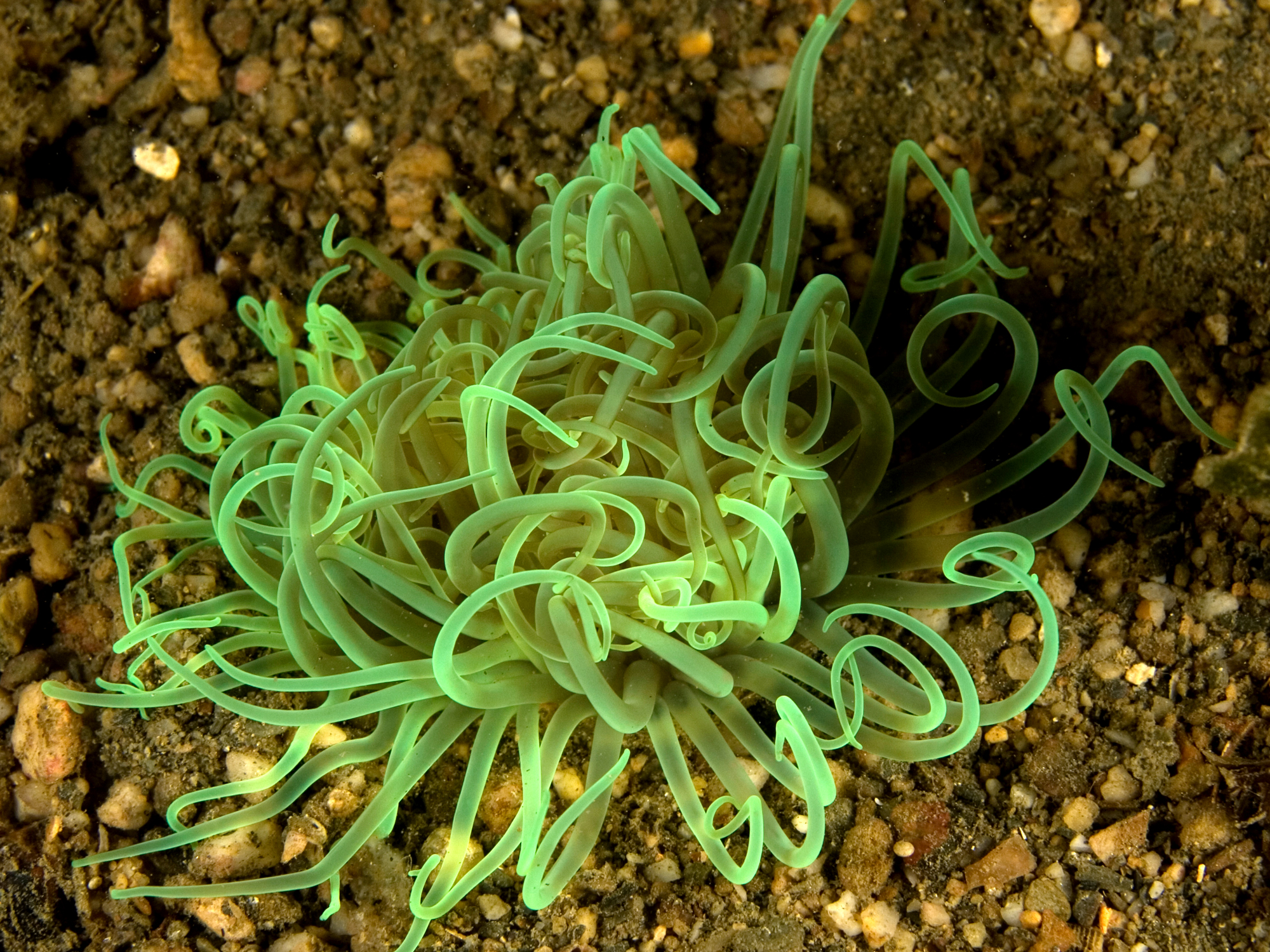

Many cerianthids have vivid pigmentation, and fluoresce brightly under actinic lighting. Photo by Jimmy Hoehlein (image reproduced with permission of copyright holder House of Fins).

Cerianthids can burrow in a variety of sediment types, but prefer those with greater amounts of silt and fine sands. Photo: Nick Hobgood (Wikimedia Commons), CC-By-SA.

0 Comments