By Richard Aspinall

I’m fortunate in that several editors over the years have allowed me the opportunity to share my interests with a wider audience, not just in terms of reef keeping, but in my deep and abiding passion for visiting, exploring and taking inspiration from the real thing.

I’m fortunate in that several editors over the years have allowed me the opportunity to share my interests with a wider audience, not just in terms of reef keeping, but in my deep and abiding passion for visiting, exploring and taking inspiration from the real thing.

I have written at length about how my other great interest of scuba and underwater photography has influenced and guided my reef keeping journey and I have often argued that visiting a real coral reef, after learning to scuba or with simple snorkel and mask, should be on every reefer’s ‘bucket list’.

Visiting a reef, whether you are fully kitted up with thousands of pounds/dollars worth of complex equipment or whether just floating languidly at the surface with a snorkel and fins from a beachside store can be a life-changing experience for anyone, but for a marine hobbyist can offer a new perspective. Once you’ve seen fish and invertebrates in their natural home and witnessed their complex relationships and behaviors on the reef you may well regard the stock you purchase in the store back home, with more consideration and I would hope more awareness that the chance to keep these creatures in captivity is a privilege.

I would go further and argue that once you’ve enjoyed the wonder and splendor of a healthy coral reef you will never think of the hobby/industry in the same light again. For me it has definitely engendered a far greater awareness of the potential damage that unregulated and unsustainable harvesting of marine creatures can cause as well as the corollary of this pattern of exploitation – the opportunity to harvest reef fish and invertebrates sustainably and for a price that creates incentives to protect reefs from destructive harvesting patterns coupled with the monitoring and enforcement infrastructure to ensure such a system is policed.

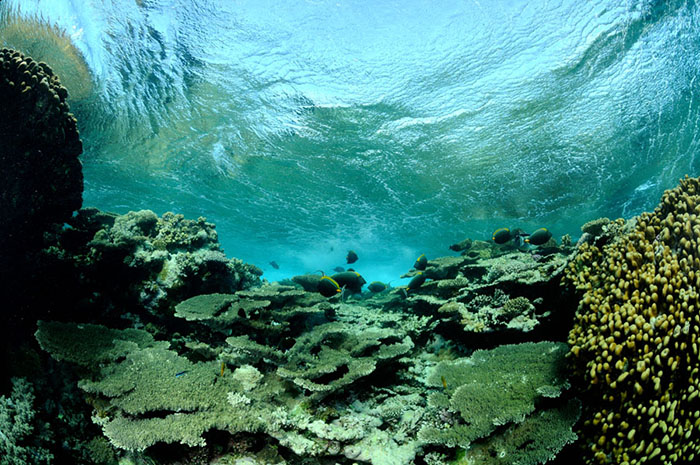

The reef crest – a complex, high-energy and oxygen-rich area of the reef. There’s a lot going on here – it is a structurally diverse and dynamic area.

Whether this happens or not may be a distant and optimistic dream, but every time a tourist visits a reef or a sustainably harvested fish is purchased for a few dollars more than its counterpart then potentially, a message is sent.

But enough of my personal beliefs about the future shape of the hobby, let us discuss the other great potential role that exploration of tropical reefs can offer – a great deal of inspiration and a greater understanding of the habitats we endeavor to keep at home.

Reef Zonation

Any text book on marine biology or coral reef structure will at some point in the first chapter or two include a line drawing of a section across a ‘typical’ reef. It will also go into far greater detail than I am able to do in the short piece, but on the upside I can promise there will be no graphs!

Some aquarists do not consider the ‘wild’ as relevant to them and their charges, but I would argue it should be. Personally I want to know as much about my aquarium’s inhabitants as possible and knowing the lives they had (or would have had) if they were still in the wild is important to me on a ‘knowledge for the sake of knowledge’ basis as well as a practical one – am I replicating the right conditions for their long-term needs and in the case of some species am I capable of replicating the conditions they need for basic survival?

In this article then I will explore, using my own observations and photographs the structures, zones and morphology of coral reefs and hopefully offer some inspiration for aquascaping. I intend to use a fairly standard method of classifying reef zones and will work from the shore outwards.

The Fringing Reef

Fringing reefs literally ‘fringe’ the land, from the shore line to the reef platform. Needless to say, some reef structures such as atolls do not have a fringing reef and just contain a central sand-filled lagoon bordered by reef platforms, but for the majority of reef structures that are found around coastlines the fringing reef is the norm.

The ecology of the shore can be complicated and depends on ocean current, local geography and geology, human impact and location on the globe and is outside the scope of this article. These factors can heavily influence the shallowest of the potential habitats within the fringing reef – the lagoon. Lagoon systems have often been overlooked in the role they play in regulating and controlling sedimentation, nutrient cycling and physical refugia for larvae and juvenile species. Lagoons are somewhat lacking in allure for divers and understandably not an aquascape many will wish to recreate. We must acknowledge though that every habitat will hold a unique fauna, whether we find it interesting or not.

One of the richest habitats found in tropical waters is the mangrove forest that can develop along shallow and estuarine areas where current and wave action allow. Mangrove propagules vary, by species in their longevity and buoyancy and thus their ability to distribute themselves using ocean currents and tidal reach. This can result in large monocultures but on occasion quite complex zonation of differing species with some forming stands on ‘over wash’ lands and others colonizing areas as they become more suitable due to sediment accumulation.

Between the mangrove area (if it exists) and the deeper lagoon are areas of sediment that are made from simple coral sand eroded from the reef, or more complex mixtures of sediments and muds and frequently exposed sediments rich with bivalves and large expanses of marine algae such as Caulerpa species.

So far, few hobbyists tend to try to replicate these environments, though the mangrove dominated refugium has become quite commonplace, though a true mangrove biotope that looks the part tends to be the preserve of the public aquarium.

Occasionally some shores can include a rocky component, where large boulders (we can include breakwaters and piers here) can be seen. These offer some fascinating exploration for aquarists who can explore with ease, though falling in and making an *** of your self is a risk! I’ve spent many a happy hour exploring these habitats whilst the tide is slowly heading up the beach and happily playing with my camera bag.

Rocky shores can offer habitat for many species we keep at home. These ‘rock hermits’ as they tend to be loosely called spend a great deal of their time grazing above the water line – not a lifestyle choice they can enjoy in our home aquaria.

The next zone we might encounter in our ‘typical’ reef is one that is of significant interest to many hobbyists and one that supports a unique mix of species – the sea grass bed.

A tropical sea grass community, in this case Halophila ovalis. These habitats can trap sediment and process nutrients into biomass that through the actions of the tides can find its way onto the reefs for consumption by fish. I have often witnessed several fishermen collecting ‘weed’ from this and other habitats to bait fish traps at sea.

A typical sub tropical sea grass community – again note the sediment trapping within the grasses’ rhizomes. This habitat in the Adriatic can host species as diverse as meter high Pen Shells to sea horses and in a wider global setting provide grazing for marine turtles and rare herbivores such as Dugong.

Sea grass beds are threatened across the world as are the species that thrive within them, a harbor development with moorings that can drag across the sea floor can decimate a sea grass habitat

Anyone wishing to develop a sea grass community at home will need to replicate natural conditions including high light levels; deep sediment and can for once forego the strong and powerful currents that are the norm in our hobby. Flow in sea grass areas is often limited to the ebb and flow of the tide, though not exclusively, especially in sub tropical and temperate regions where sea grass beds can be more extensive.

We have now moved many meters from the shore in our exploration of our hypothetical reef. The distance from the shore to the maximum low water mark can be a few meters or several hundred and very often this distance and the overall structure that we explore is shaped not just by geography but life processes as well.

Heading away from the coast we pass through a process of reef–building that has taken many thousands of years. As we leave the lagoon/shore complex area with its white sand we enjoy so much on vacation we are reminded of the dynamic nature of these environments – what we are exploring is in many instances the eroded remains of coral reefs from centuries ago.

This small atoll in the Maldives was entirely created from coral and shows the division between the fore reef and the slow change in structure as you head landwards to the shallow lagoonal area.

I thought I’d include this shot of a temple in Male, the Maldivian capital – the building and the gravestones are all carved from ancient coral.

As the levels of sedimentation increase and the ‘land takes over’ the coral structures that will merge with the back reef become eroded, overgrown with algae and with time a complex structure of micro atolls will form that were once part of the reef flat, but as the reef forms and heads seawards, become isolated, surrounded with sand and lose much of their species diversity. Such areas usually offer little interest but in some cases this does not hold true. Whilst over the course of decades if not centuries the micro atoll area will eventually become sand-filled it can host some sheltered though time-limited habitats.

This sorry sight was once a large coral head in the lagoon zone, now silted up and covered in algae. This habitat is the result of a hotel development which has destroyed a thriving fringing reef community. Whilst the lionfish seem content they appear to have little prey for the long term.

This small community with its pair of Amphiprion bicinctus was photographed in a sand filled lagoon where a few remaining and mainly eroded coral heads offered attachment sites for soft corals and an anemone.

This reef in the Red Sea is useful to illustrate reef structure. Existing within a reef/lagoon complex within relatively shallow waters this is an isolated reef not tied to any particular shoreline and thus without the fringing reef structure. A central lagoon of eroded sand is forming in the centre of the structure.

Sandy bottoms offer opportunities for specialist feeders such as this blue spotted ray (Taeniura lymma).

The Reef Platform

The next major zone is what I will choose to call the reef platform, consisting of the back reef, the reef flat and the reef margin or reef crest. These terms may be somewhat interchangeable but in essence we are talking about the ‘reef –proper’, here, the large and massive expanse of coral rock stands as a bulwark to the ocean. To the rear of this structure are more sheltered areas of coral growth that due to tidal and wave action are regularly flushed with plankton and oxygen-rich water. These coral habitats as yet have not begun to erode or succumb to damage and are at their prime and may be the very pinnacle of coral formation, sheltered as they are from extremes of current and weather – coral formations may be exceptional.

Sheltered areas like this can often be very similar to the corals formed within surge channels within the reef flat and can form extensive networks that offer shelter to shoaling fish. They are also of significant interest to aquarists as they often hold numerous species we are familiar with from our own systems – tridacnids are especially numerous.

The reef flat is a very different place altogether, even though it can be separated by a matter of a few meters from the splendor of the reef margin and back reef. The reef flat is exposed to the pounding of the oceans and the coral growths found upon it tend to be robust species like Pocillopora, though coral diversity tends to be variable – this area is rich in algae and tends to be where the big tangs will be found. Sadly many divers ignore this wonderful landscape and will usually ask me what I’m doing splashing around in the shallows, but for me this is one of the most interesting areas of any reef.

This Red Sea reef flat isn’t exposed to too much pounding from the waves and is on the leeward side of the reef structure, hence corals can flourish. Note the Acanthurus sohal in the distance.

Another Red sea reef. The island is actually a reef itself formed many thousands of years ago and now exposed due to changes in sea level. In this example the reef flat merges with a very thin sandy area. The reef crest and the wall are particularly interesting though.

The reef platform is one of the most dynamic areas of any reef, here the corals are growing at their maximum capacity and as they are continuously eroded and fractured by wave action sandy material is washed towards the lagoon. It is also the area where we can experience the high-energy reef margin or reef crest zones that many of us aspire to replicate in our home systems.

This image demonstrates the complicated structure of many reef crests, with corals overgrowing corals.

The reef crest is perhaps the area best described as ‘where the action is’, here we can see a huge amount of coral growth and a great deal of fish life. From Anthias to Fusiliers this is where the light and the waves combine to provide a great deal of planktonic nutrition.

This shot was taken at sunset, but shows the huge numbers of fish species that inhabit the shallows.

Whilst the reef crest is one of the most diverse areas of the reef in terms of species present it is also one of the most dynamic. In many of these images you will note corals growing on top of corals. As some specimens die they become overgrown by others whilst others are shaded by tabulate species and suffer the same fate. This creates a very structurally diverse habitat with numerous overhangs for fish to shelter and of course for non photosynthetic and low light tolerant species to prosper.

All of this coral growth has to go somewhere of course and as the corals constantly over grow each other, the effects of gravity (aided and abetted by occasional storms) takes its toll and large coral structures break away.

Whist we might consider the collapse and fall of large coral colonies to be a tragedy, it is the absolute norm and in doing so the corals’ fall will create new opportunities for life on the reef crest and the rubble zone below.

I have often discussed with divers and dive guides the dynamic and the rapidly changing nature of these areas. There is on occasion a belief that coral reefs are very static places with any change occurring over hundreds of years. Indeed many species can grow rapidly to fill any void created. They in turn will be succeeded by others and the reef as a whole marches ever further from the shore. Before we look at the rubble zone created by this ever present, if slightly massive ‘rain’ let’s consider the wall or the outer reef slope.

Back when pilling live rock against the back wall of our aquariums was de rigeur, (Bommies seem more common these days – yes I’m looking at you Mr. Fellman), and our systems closely resembled small versions of the reef slope.

Reef slopes, walls or drop offs, Call them what you will are very variable. They can be a few meters deep or many hundred. They can catch a great deal of sunlight or very little and can be exposed to high levels of current or be sheltered by geography. They are the hardest to quantify yet will always see the greatest stratification in terms of species found as one travels downwards and the available light decreases. Given the lighting levels, one often finds numerous species which rely more heavily, if not entirely on plankton for their nutriment.

These superb gorgonians, over a meter across tend to be found growing in deeper waters at right angles to current. Interestingly they prime habitat of the Long Nosed Hawkfish often found in the company of Lyretail Hawkfish.

Other filter feeding species such as feather stars, basket stars and other ‘gorgonians’ such as whip corals are common place, with many being solely active at night.

This feather star has chosen a rocky pinnacle on the wall on which to settle before unfurling its ‘arms.’

It is interesting to not that many of the species described here are the ones that are often present significant difficulties in captivity. This is further emphasized by the presence of neptheids in such habitats, which are widely regarded as unkeepable by the vast majority of hobbyists.

Reef slopes can be fascinating places, but don’t offer as much inspiration for the aquarists as the shallower areas or perhaps the next of the zones I’d like to look at. I’m glossing over azooxanthellate systems in favor of a more generalist approach, but for anyone interested in the entirely non photosynthetic corals and inverts – this might be the zone for you.

As noted earlier the constant fall of debris from the reef crest carries material to a rubble zone, which depending on local conditions may be many scores of meters deep or comparatively shallow and capable of supporting photosynthetic life. Occasional surge channels in the reef complex may allow sand that has collected in the lagoon areas and on the back reef to run through the reef platform and contribute to large expanses of sandy bottom, which can be excellent for species such as Garden Eels.

Whilst this acropora may look like it belongs here it has in fact fallen from the reef above. It now provides shelter for a shoal of Heniochus.

Rubble zones are a constant feature of reefs and as the reef structure forms they too will move seaward. They can be fascinating places to explore and are replete with interesting fish life. The sandier areas as noted provide habitat for several specialist groups of fish, but for the aquarist the presences of shrimp gobies is especially interesting. For the underwater photographer the presence of very skittish shrimp goby/pairs can be very frustrating.

Pseudochromis flavivertex (left) and Anampses twistii (right) hunting for crustacean prey amidst the rubble zone.

Commonly these expanses of sandy feature pinnacles and bommies. These can vary in size from a few meters across to structures that are almost reefs in their own right. The smaller ones that may have been formed from falling reef material and have come to rest on the substrate may become colonized by corals and will grow in size before being consumed by the reef as it moves ever outward. These bommies are absolutely fascinating and offer a great deal of inspiration to aquarists keen to recreate an authentic reef scape. Though an awful lot of two part epoxy and some supporting structure will be required.

This bommie ‘field’ shows some great structures – the one on the left would be a challenge to recreate, and is made all the more interesting by the encrusting sponge at its base.

Close

I hope this whistle stop tour of some of my favorite parts of a coral reef has been of interest. I hope it offers some insight into the complex processes that are involved in the natural formation of a reef – these are not static places where change occurs over millennia. These are vibrant places where destruction is part of formation and through this dynamism new opportunities are presented for reef building.

0 Comments