By Joe Rowlett

Angelfishes of the genus Genicanthus are some of the most recommendable species for home aquarists. They are small in size, peaceful, (mostly) coral-friendly, and attractively colored. They range across the Indo-Pacific, hovering above the seaward slopes of moderately deep reefs. This is a habitat quite different from the typical reef tank, but these fishes seem to cope just fine with the foreign surroundings. Their natural diet is reported to be mostly composed of pelagic salps—small gelatinous creatures related to sea squirts. Again, this is quite unlike the diet they receive in captivity, but they seem to make due. Their zooplanktivorous ecology helps to explain why they tend to behave themselves around corals.

The angelfishes of the genus Genicanthus are some of the most recommendable species for the home aquarist.

Despite their popularity, little information is available regarding the evolutionary relationships of the various described species in Genicanthus. The last major treatment was a morphological revision of the genus published in 1975 by Dr. John Randall, which included hardly any discussion on the phylogeny of the group. Since then, only a single species has been described, G. takeuchii, and there is little reason to believe any other unknown taxa remain to be discovered.

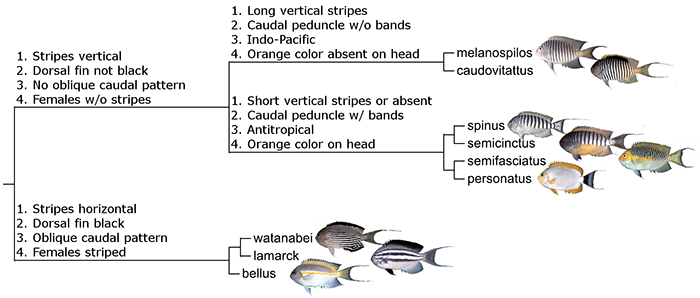

This article will aim to present a preliminary phylogeny for Genicanthus, based on a combination of previously published morphological data, biogeography and color patterns. In putting this together, I found most of the relationships to be straightforward, though a few questions remain. Genetic study, as always, is required to confirm these hypothesized clades.

The caudovittatus Group

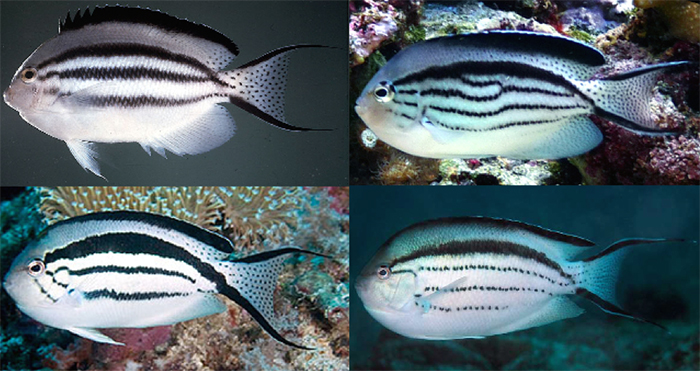

This is an easily recognized species pair which differs from all others in the genus by the male’s coloration of black vertical stripes which extend the full height of the animal—the similarly patterned semifasciatus group has the stripes ending midway along the body. The females are a light brown-grey ventrally, blending into a yellow-grey dorsally, with black bars on the upper and lower margins of the caudal fin.

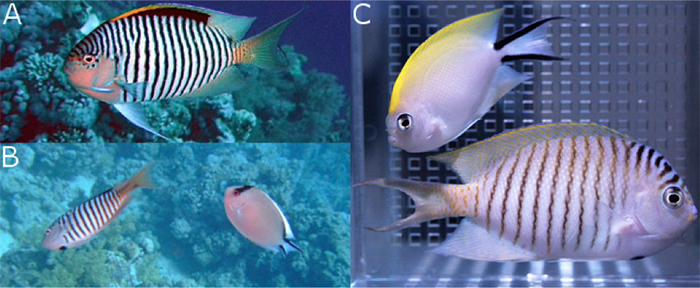

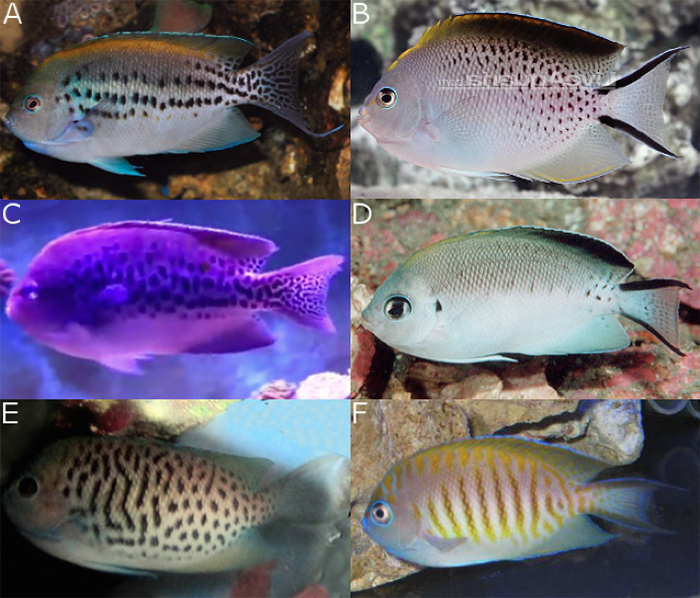

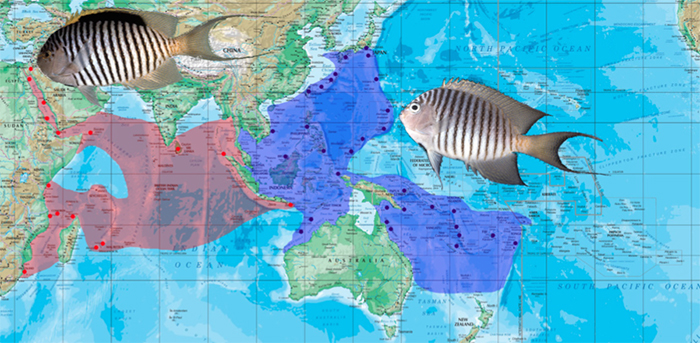

A) G. caudovittatus male, Egypt. B) G. caudovittatus male & female, Egypt. Note the spotted breast in this specimen. C) G. melanospilos, male and female. Photos by Hanadai, yakafine, and Freewater.

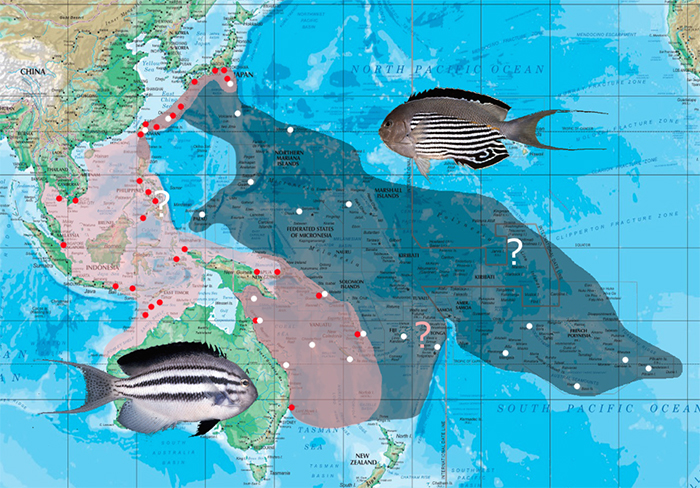

The Zebra Angelfish G. caudovittatus is found in the Indian Ocean, from the Red Sea, south along the African coast and east to the Andaman Sea and Bali. In Bali—the easternmost limit of its range—it overlaps (and likely hybridizes) with its Pacific sister species, the Spotbreast Angelfish G. melanospilos. This species occurs throughout Indonesia, north to Japan and southeast to Australia, but is absent from much of the Central Pacific. The Indian/Pacific Ocean split is a common occurrence in many groups of fishes, but, strangely, all others in this genus are restricted to the Pacific Ocean. Is this perhaps evidence of this being an older lineage which has had more time to spread across the oceans, or is there some other quirk of this species pair which allows them to disseminate more freely across geographic barriers?

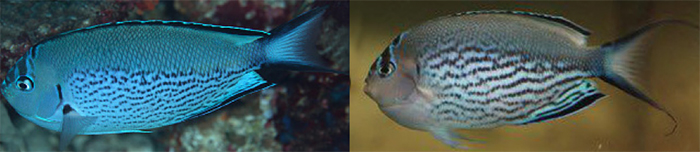

Female G. caudovittatus (left) and melanospilos (right). Photos by I Segreti del Mare and himechanz.

To tell these two lookalikes apart: 1) The dorsal fin of male caudovittatus have a large black mark in the middle, absent in melanospilos. 2) The ventral region just before the pelvic fins has a large black spot in melanospilos (Greek: “black spot”) which is usually (but not always) lacking in caudovittatus 3) The females of caudovittatus have an extension of the upper caudal fin stripe which extends along the dorsal fin base. Both species are common and relatively affordable aquarium imports.

The semifasciatus Group

The four species in this group share an interesting antitropical distribution, apparently unique within the entire angelfish family Pomacanthidae. The Japanese Swallowtail Angelfish (G. semifasciatus) and the Masked Angelfish (G. personatus) from Hawaii are northern sister species, while the Halfbanded Angelfish (G. semicinctus) and Pitcairn Angelfish (G. spinus) are a more southerly pair. The vast stretch of ocean dividing these two regions is presumed to be devoid of any related species, which raises the obvious question of how these taxa speciated across such a large expanse.

More so than their congeners, these are deepwater species which presumably dwell beneath thermoclines. In regions where they are found in shallower waters, there are cooler surface temperatures due to either deepwater upwellings or higher latitude. This is seen most prominently in personatus, which is a rarity at SCUBA depths around the main Hawaiian Islands but can be found more shallowly in the subtropical islands which stretch to the northeast. The last common ancestor of these four must have either dispersed (likely during the larval stage) along coldwater currents linking these regions or, instead, existed during a period of cooler surface waters along the Equatorial Pacific. This antitropical range is not unheard of in other reef fishes (e.g. Cirrhilabrus jordani/claire & Pseudojuloides atavai/cf atavai), but our understanding of how such speciation occurs is incomplete.

These four species share a similar male color pattern of thin vertical stripes which extend to the middle of the body, though this feature is apparently lost in personatus. The females share a black band near the base of the caudal fin, as well as a black marking above the eyes, though spinus has apparently lost these features. The females of this semifasciatus clade are in fact quite like those of caudovittatus/melanospilos, which may indicate a sister relationship; the similar male patterning lends further support.

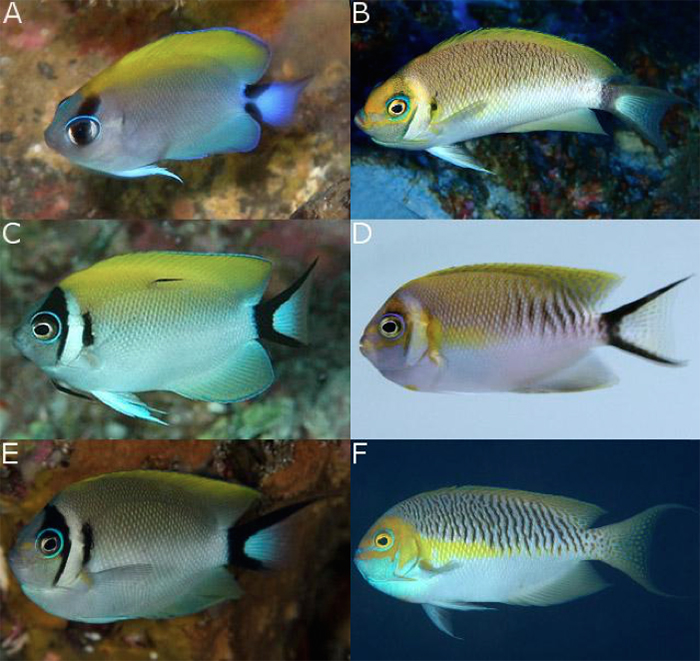

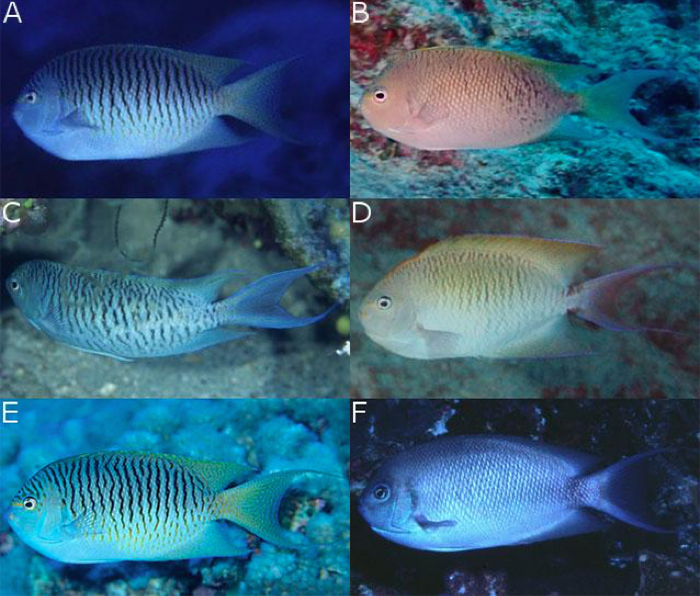

Ontogeny of G. semifasciatus. Photos by Rubiena, Kyo Yunakawa, 今川, B-box Marine, Masamichi Torisu, and Tetsu.

G. semifasciatus—found in Japan, Guam and the Northern Philippines—is easily recognized in the male sex by its many thin stripes and the golden mask which extends along the midline of the body. Females are dingy dorsally, with paired black markings on the head and connected black lines on the caudal fin. This is an uncommon and somewhat expensive fish in the aquarium trade, prone to bacterial infections. Successful longterm husbandry would likely benefit from water temperatures kept around 70°F.

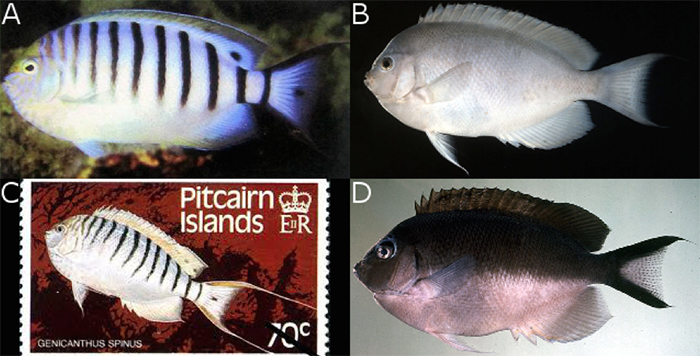

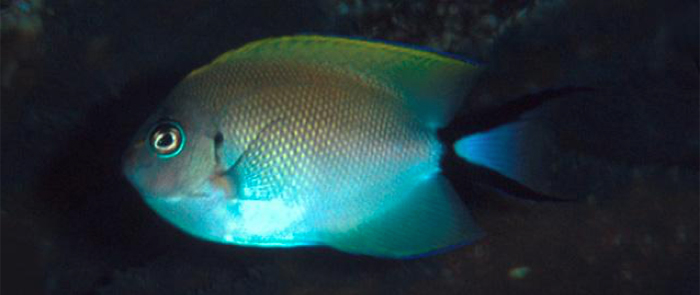

G. personatus (Latin: “masked”) occurs throughout the island chain of Hawaii and Midway Island. Nearby habitats, such as Johnston Atoll and Wake Island, are not known to harbor this species, but it may yet be found in these regions (or at surrounding seamounts) at greater depths. This is arguably the most beautiful of the Swallowtail Angelfishes, with mature males recognized by the deep amber hue of the dorsal and anal fin margins and the eponymous “mask” covering the face, which contrasts vividly against a body colored a brilliantly alabaster white. Females share with the males a black band at the base of the caudal fin, but they differ in having white fins and a black mark covering much of the head, which diminishes in size as the females mature. Precious few wild specimens have been collected for the aquarium trade, but mariculturist Karen Brittain has succeeded in breeding and raising this species in captivity, with the captive-bred offspring offered to those aquarists willing to spend a princely sum.

The southern members of this group are far less familiar in the aquarium world, with only a small number of specimens of G. spinus having been exported from the Cook Islands and perhaps a single individual of semicinctus (collected from an unknown locality) having appeared in Japan. The range of spinus extends eastward to encompass French Polynesia and the Pitcairn Islands; it is currently unknown from neighboring regions such as Easter Island or the Marquesas. Further west can be found the closely related G. semicinctus, known only from Lord Howe Island and the Kermadec Islands north of New Zealand. Separating the Kermadec and Cook Island populations is a deep ocean trench, presumably inhospitable for dispersal between these regions.

Few images exist of either species, and little is known of what variation may exist within either taxon. They differ from all others in the genus by having a higher count of scale rows (49-54 vs. 45-48), indicative of a particularly elongate body. The western semicinctus is a stunning fish in the male sex, with relatively thick black stripes extending to the midline of the body. The head and dorsal fin are a continuous orange, showing a perfect blending of the pattern seen in the northern semifasciatus/personatus. The unmarked ventral half of the fish is a saffron yellow, extending into the anal fin. And the region surrounding and beneath the mouth is overlaid with a convoluted mesh of blue lines.

A,B,C) G. spinus, males, females, and stamps. D) G. semicinctus female. Photos by Makoto Matsuoka and John Randall.

The male of the eastern G. spinus is similar in most regards, seeming to differ in the absence of yellow ventrally and in the dorsal fin. The holotype specimens, collected at the Pitcairn Islands, were uniformly grey, but photos of aquarium specimens indicate that some yellow develops anteriorly and dorsally to the eyes. Females of spinus are a uniform grey, with a bluish tint to the caudal fin margins and dorsally on the head. G. semicinctus females have a dusky-grey dorsal half, as well as a dark mark above the eyes rimmed in periwinkle which blends into a cobalt blue nape. Opercular markings are present, albeit faintly, which are nearly identical to those seen in females of semifasciatus, further supporting the shared ancestry of this group.

The lamarck Group

The three species comprising this group are recognizable by the longitudinal lines present in the males of each species, as well as the black dorsal fin and the prominently patterned females. Furthermore, each species shows a similar pattern of an oblique line extending anterodorsally from the lower caudal fin margin, though this feature is present only during certain developmental stages in each species. Consider the angular grey back of male G. watanabei and the female patterning of G. lamarcki and G. bellus and it becomes clear how these three form a single lineage.

Lamarck’s Angelfish (G. lamarck), named for the famed 18th century French zoologist, is by far the most abundantly seen swallowtail angelfish species offered for sale, often costing little more than the price of a clownfish. This low cost is due to the relatively shallow waters (10-50m) that it calls home, as well as its wide range throughout the aquarium-collecting regions of the West Pacific. Perhaps because of its ubiquity, the beauty of this species often goes underappreciated.

Females sport a characteristic black line arcing from the eye to the lower margin of the caudal fin—a feature somewhat reminiscent of the freshwater Penguin Tetra. Two or three thinner black stripes are spaced below this, while small black speckles fill the caudal fin and portions of the anal fin and dorsum. Males are similar but ultimately lose the arcing line, replacing it with additional black stripes. In both sexes, the number, thickness and shape of these stripes is highly variable. In some specimens, these lines extend to the eye, forming a sunburst pattern, while in other specimens they end abruptly near the operculum. The significance of this variety—if it’s age dependent or biogeographic or neither—is unknown.

The Watanabe Angelfish (G. watanabei), named for Japanese ichthyologist Masao Watanabe, is the apparent sister species to lamarck, ranging from Japan and Australia east through much of the Central Pacific. There is an apparent discontinuity near the equator which seems to split the species into discrete northern and southern populations, though this could potentially be an artifact of our poor knowledge in these waters. This is a far rarer species in captivity, commanding many times the price of lamarck, presumably due to the limited aquarium collecting done in much of its range.

G. watanabei is easily identifiable, with males sporting 8-11 horizontal black stripes running along the ventral portions of the body and into the anal fin. Dorsally, a glaucous “swoosh”—similar to the pattern seen in female bellus—obfuscates the underlying stripes. Interestingly, portions of these stripes along the midline turn yellow where they are overlaid with this “swoosh”. The pelvic fins of males are white (versus black in lamarck), and the dorsal fin is mostly black, save for a blue margin and a white patch near the rear of the fin.

Females are mostly bluish-white, with black margins to the dorsal, anal and caudal fins. Above the eye is a black band margined in light blue, with a similar marking above and below it. There is generally little apparent variation to the color patterning in this species, though note that the number of stripes in males increases with size.

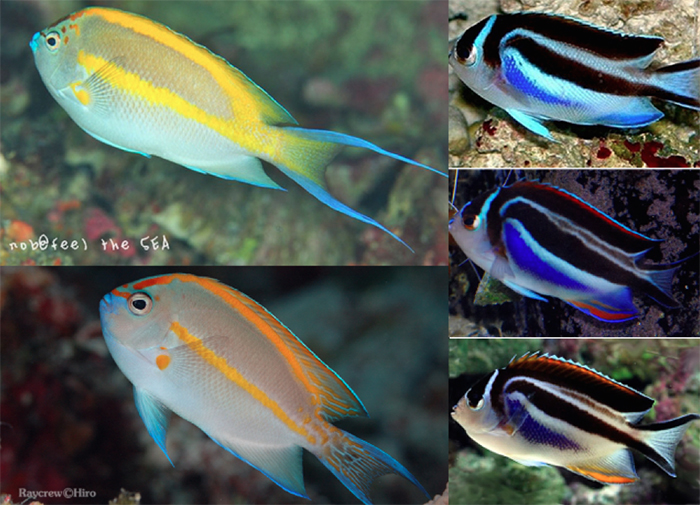

G. bellus (Latin: “beautiful”), known varyingly as the Ornate Angelfish or the Bellus Angelfish, is instantly recognizable for it’s unusual coloration in both sexes. Males are a dingy, beige-white, with prominent longitudinal yellow stripes dorsally and along the midline which converge near the caudal peduncle. This yellow coloration spreads into the dorsal fin of males, while the female has this fin colored black basally. The female coloration is particularly complicated, consisting of an angular blue brushstroke, above which runs a thin white stripe and a much thicker black stripe that continues into the lower caudal fin margin. A mark reminiscent of the Nike “swoosh” extends along the dorsal fin and projects downwards onto the operculum.

Variation in male and female G. bellus. Photos by nob@feel the sea, hirochan, unknown, Giovanni, and woliverjr.

There seems to be some amount of intraspecific variation in bellus, but the extent and significance of it is poorly documented. The anal fins of females vary from blue to blue with orange stripes to white with orange stripes. The extent of the lateral blue “brushstroke” is likewise variable in thickness. In males, the yellow of the caudal peduncle can vary from solid to highly filigreed, but there appears to be no biogeographic pattern to this variation.

This is a particularly deep-dwelling species, known from 50-110m. In spite of this, it is still a fairly common and surprisingly affordable aquarium fish, but decompression issues are not uncommon with bellus, so it is wise to avoid purchasing specimens swimming in a bobbing, head-down motion. It has a broad range that encompasses nearly all of the West and Central Pacific Ocean, including the Cocos-Keeling and Christmas Islands in the Eastern Indian Ocean.

Hybrids and “G. takeuchii”

Genicanthus has a number of species with overlapping ranges, and it should come as little surprise that several hybrids are known. Surprisingly, most of these hybrids seem to occur between the various clades rather than within them, which might suggest that this is a relatively recently evolved genus. This was in fact confirmed to an extent by the recent molecular study of Gaither et al 2014, which indicated that Genicanthus is similar in age to far less diverse clades (e.g. the oft-hybridizing Eibli+Lemonpeel+Pearlscale Angelfishes).

A,B,C,E) lamarck X melanospilos. A & C are the same individual. D) lamarck X semifasciatus? F) semifasciatus X bellus? Photos by Jimmy Ma, LiveAquaria, Jimmy Ma, H. Onuma, unknown, and unknown.

G. lamarck has an overlapping range with four other species, at least two of which it has been documented to have potentially hybridized with. Its sister, watanabei, is sympatric with it in several regions (particularly so in the Coral Sea), but, surprisingly, hybrids are not confirmed for this pair. Suspected lamark hybrids typically show signs of a spotted caudal fin or a black dorsal fin, often with a trace of the oblique caudal patterning present.

Hybrids and variations of melanospilos, all but C from Japan. D) the yellow nape suggest lamarck X melanospilos. C) From Fiji, melanospilos X ???. Photos by Osamu Morishita, UniMotto, Noboyuki Kobayashi, Yukako, unknown, and Shoichi Kato.

G. semifasciatus seems to be a particularly promiscuous piscine. Seen above are images captured at the Izu Islands of Japan, where it has apparently mated with melanospilos. Notice in the male how the stripes extend an intermediate distance along the sides, as well as the lack of the characteristic black pelvic spot of melanospilos or the golden face and stripe of semifasciatus. The female likewise blends characters, showing the caudal band of semifasciatus, but lacking the expected opercular markings for that species.

The islands just south of this region are variously known as the Bonin or Ogasawara Islands. It is here that one of the more intriguing mysteries of this genus can be found in the form of Genicanthus takeuchii, an alleged species endemic to this region and the nearby Marcus Island to the east. If you’re familiar with the patterns of reef fish biogeography, this tiny region is an unlikely place to find an endemic fish—particularly a relatively large angelfish with a pelagic larva. This raises some red flags, as there needs to be some plausible mechanism to explain why such an isolated species is unable to expand beyond its range.

In examining takeuchii we can see a strange pattern completely unlike any other in the genus, particularly in the juveniles and females. The fact that the female has any significant patterning at all would indicate it belongs within the lamarck clade, but the thin, irregular stripes are going the wrong direction, and there’s no oblique pattern associated with the caudal fin here. The stripes of the male are reminiscent of lamarck in their coverage, but they only extend halfway down the body… a very semifasciatus-like trait. And let’s mention the juvenile, whose blotchy pattern is completely unique in the genus, though with a possible analogy seen in the markings on the head of female watanabei or in the above bellus X lamarck hybrid.

The biogeography and morphology might have clued you to what is going on here, and the photo below should clinch it—we see an aberrant G. semifasciatus cavorting around with a flirtatious takeuchii, giving us ample evidence that this “species” is really nothing more than a regionally abundant hybrid of semifasciatus and (likely) lamarck. This latter species is only known from the nearby Izu Islands, so any straying south to Ogasawara would be rare and unlikely to find a mate of their own kind.

Aberrant semifasciatus with female takeuchii, showing color development of a single specimen. Photos by Koba-Tan.

There seem to be a couple variants present here: one with a strongly lamarck-like striped appearance, and the other with a clear semifasciatus-like countenance. The question arises as to how we can explain this diversity. Are we seeing in these two forms hybridization resulting from different parentage—male semifasciatus X female lamarck and vice versa? Or are we seeing backcrossing of a hybrid with one of the parent species—hybrid X semifasciatus or lamarck?

A third possibility exists, and this is the most exciting of all. Perhaps takeuchii is an example of “hybrid speciation,” wherein a hybrid is unable to successfully breed with anything aside from other similar hybrids. This creates a reproductive barrier limiting gene flow with the parent species and could allow a small number of individuals to create an entirely new species in an isolated range. We may have an example to compare this to—Centropyge shepardi, a Dwarf Angelfish found just to the south in the Mariana Islands, which happens to bear an uncanny similarity to the hybrid of the Flame and Rusty Angelfishes.

So what is it we are witnessing here with all these strange, miscegenated pomacanthids endemic to the Izu-Bonin-Mariana Arc? This region does act as something of a crossroads for West Pacific and Central Pacific taxa, but why are there no takeuchii known from areas to the west where both parent species overlap? Is it that the parents species are both too abundant to incentivize their mating with each other, while their rarity further east forces them into this flagrant delicto. If so, it could explain the ability of takeuchii to sustain itself as a viable species. Ultimately, genetic studies are required to tease apart what is occurring here. Captive breeding of Genicanthus has been proven possible, and this would be an exciting avenue to research this.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to LemonTYK for sharing his insights and photos. Other photo credits: males (in maps): John Randall; G. semicintus male (introduction): Pro Dive Lord Howe Island

References

Gaither, M.R., J.K. Schultz, D. Bellwood, R.L. Pyle, J.D. DiBattista, L.A. Rocha, B.W. Bowen. 2014. Evolution of pygmy angelfishes: recent divergences, introgression, and the usefulness of color in taxonomy. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 74:38 Ð 47.

Pyle, R.L., 2003. A systematic treatment of the reef-fish family Pomacanthidae (Pisces:Perciformes).Ph.D.Dissertation,University of Hawai’i,Honolulu,p.422.

Randall, J.E., 1975. A revision of the Indo-Pacific angelfish genus Genicanthus, with descriptions of three new species. Bulletin of Marine Science v. 25 (no. 3): 393-421, 1 pl.

0 Comments