By Richard Ross

In the previous two installments of Skeptical Reefkeeping, we talked about how applying skeptical thinking to reefkeeping can help you make decisions about what methodology to follow or which products to use. In this installment, we’ll spend less time exploring the skeptical method, and instead examine how skeptical reefkeeping has impacted, and continues to impact one particular aspect of our hobby: making our hobby more environmentally sustainable.

A brief reminder

Skepticism is a method, not a position. Officially, it’s defined as “a method of intellectual caution and suspended judgment.” A skeptic is not closed minded to new ideas, but is cautious of ideas that are presented without much, or any, supporting evidence. In our hobby there are tons of ideas presented without much, or any, supporting evidence. Being a skeptical reefer essentially boils down to taking advice/products/new ideas with a bucket of salt. Being a skeptical reefkeeper requires that you investigate why, how and if the suggested ideas actually work. As a skeptical reefkeeper, you decide what is best for you, your animals, and your wallet based upon critical thinking.

That sounds like work! Just tell me what to do!

Sorry, can’t do that. I wish I could. This hobby is not simple and there are as many opinions about how to keep our glass boxes thriving as there are people with glass boxes. The goal of this series of articles is not to necessarily provide you with reef recipes or to tell you which ideas are flat out wrong or which products really do what they say they do or which claims or which expert to believe – the goal is to help you make those kinds of determinations for yourself in the face of conflicting advice.

The drama of ‘juicing’ fish

The early 80’s was a time of glam rock, hardy elegance corals, and DIY sumps filled with hair curlers for bio media. Back then, rocks covered with hair algae were lovely, panther groupers were the hot fish, and aiptasia were considered fabu. Hardly anyone stopped to think about where animals for our reef tanks were coming from…we were all too busy just trying to keep them alive for more than a month. Fish would come into the LFS; some would make it, and some would slowly waste away despite eating well. Most of us figured we were making some husbandry mistake that resulted in the death of the fish. However, some began to apply skeptical methodology to the problem and hypothesized that the issue might have something to do with the way the fish were being handled somewhere along the way to the LFS.

Cyanide fishing kills fish and corals – which hardly seems to justify the lower prices the practice can create.

It turned out that they were right. Investigation revealed that cyanide, often called ‘juice’ was used to ‘knock out’ fish to make them easier to collect. Sounds good right? Easier to collect means cheaper, cooler animals, and everyone wants cheaper animals. However, the monkey wrench here is that cyanide is a poison that doesn’t necessarily kill the fish outright. Often, the fish seems to recover from the initial shock. It can make it all the way through the chain of custody from the collector to the exporter to the importer to the LFS to the hobbyist tank before it begins to go down hill. We now know that the cyanide can damage the fish’s ability to adsorb food; it can eat like a pig, but get little of the nutrition it needs to live. Eventually, the animal can starve to death.

Cyanide fishing presents another, even more catastrophic problem.

When a fish hides in coral, and cyanide is squirted into that coral to make fish collection easier, the cyanide also kills the coral. Think about it for a minute…if a collector squirts 100 squirts of cyanide a day to collect fish, that’s 100 patches of coral that die. If you have 100 collectors doing that every day, you get a lot of dead habitat very quickly, and dead habitat means no food or breeding areas for the fish we want in our tanks, which means less animals overall (and the corals which we now also want in our tanks are dead too). Cyanide was also being used to collect fish for people to eat (the cyanide breaks down before people eat the fish), which meant even more was being sprayed into corals and more habitat was destroyed.

People started to become aware of this issue in the 80’s when 1. SCUBA in exotic locations became more popular, and 2. the trade in live coral began to boom. Some in the industry sought to address the issue by training collectors to collect with nets and skill rather than juice. Those animals could be advertised as net-caught, which made consumers happy because they could still get the fish they wanted, safe in the knowledge that wild reefs were not poisoned in the process. A win for everyone! Let’s move on! Not so much.

As it happens, those who were skeptical of net-caught claims looked deeper. Sure enough, some collecting outfits continued to use cyanide, even after being trained to net catch, but simply said they weren’t. ‘Juicing’ fish was easier and cheaper than using nets. While some collecting outfits did net-catch exclusively, skeptics discovered that as cyanide caught fish and net caught fish made their way through the chain of custody, they were mixed together in holding facilities so there was no longer a way to differentiate between the specimens; both were sold as cyanide free.

To combat the negative press about cyanide use, the hobby was told that fish could now have a cyanide detection test (CDT) which would weed out juiced fish. Great! Problem taken care of, right? Wrong! As we know to ask from the first installment the immortal question from They Might Be Giants – ‘are you sure that that thing is true, or did someone just tell it to you’ skeptical reefers questioned the CDT. How was the test administered? Who administered it? How often? How accurate was it? How long did it take to get results? As it turned out, there was a CDT, but it was not fast, it needed to be done in a lab, and the fish had to basically be blended to carry out the test. This all made the test impractical because the only fish you could be sure was or wasn’t ‘juiced’ was converted into slurry, and a fish slurry makes an odd sort of display.

It’s not just ‘juice’

The story gets even more involved. As it turns out, cyanide itself wasn’t the only part of the collection that destroyed coral habitat. Imagine you are a collector squirting cyanide into a huge coral head to knock out a bunch of damsels. You squirt, the damsels stop swimming, but they are still deep in the coral – how do you get them out? You break the coral with a hammer or crowbar or whatever was available. When the net trainings began and collectors were trained to use a ‘tickle stick’ to coax fish from their hiding places and into a net, some of the cyanide use actually did stop, but not all of it…because smashing is faster than coaxing. Instead of knocking out the fish and then smashing the coral to get at them, the knocking out step gets skipped, the coral gets smashed and the frightened fish are netted out of their smashed hiding places. Sure, not juiced, but the habitat destruction remained practically the same.

How about now?

We hear different things. What really need is a way for the industry to act as a whole for it’s own, and the environment’s benefit. In the last decade or so, the idea of sustainable collection has really caught our hobby’s collective psyche, but is there really any way to know if the animals that are being sold as sustainable or responsibly collected really are either of those things?

Catching fish with hand nets, barrier nets and tickle sticks provides quality fish with minimal impact on the reef.

There have certainly been attempts to answer these questions. Most notably, in 1998, the Marine Aquarium Council (MAC) was established “by key stakeholders to provide voluntary standards and an eco-labeling system for the marine aquarium trade.” Unfortunately, MAC was quickly, right or wrongly attacked for myriad reasons including corruption, lack of follow up in the field and the voluntary nature and utility of its certifications. Getting actual information about the reality of these attacks or the MAC’s actual effectiveness is very difficult for a skeptical thinker because it’s just so hard to get any evidence that isn’t suspect for one reason or another. It’s hard to trust the MAC’s info because they are the ones putting it out and it’s hard to trust the detractors’ info because they often seem to have some sort of personal or professional axe to grind with the MAC.

Today, MAC’s future is unclear. What is clear is that what they were trying to do still needs to be done.

Skepticality in action

Given the above history with cyanide fishing and reef smashing, it’s no wonder that our hobby is periodically vilified as environmentally damaging. Recently, ‘Snorkel Bob’ has begun a campaign to get marine ornamental collection in Hawaii shut down completely, and he has lots of followers. Snorkel Bob’s most recent attack on the hobby was presented on the Sea Shepherds website (yes, the ‘Whale Wars’ people) as a launching point for his media tour to promote his new book and to ‘reach millions’ in his message that the marine hobby is indeed a bad thing for the planet. Essentially, Snorkel Bob says that fish collection for our hobby is responsible for dwindling fish numbers around Hawaii. Funnily enough, these attacks seem to be lacking the kind of skeptical and critical thinking that we have been discussing.

Notice the pile of dead coral skeleton in this picture. Does it point to poor collection/husbandry practices or is it simply the nature of the hobby?

Bob Fenner was one of the first to publicly react to Snorkel Bob’s statements questioning many of the claims made by in ways that make a skeptic proud. (http://www.coralmagazine-us.com/cont…bby-commentary ).

Fenner points out that the numbers of fish being collected is widely debated, that a lot of fish are collected as food, that other impacts on those fish populations (golf course run-off and food fishing) are significant, but often ignored, and that Snorkel Bob runs a reef tourism operation which surely impacts the wild reefs around Hawaii – thousands of people (transported by polluting motor boats) covered in sunscreen, body soaps, and toxic bug repellants, brought to the same spots, day after day, week after week, year after year to flail about on the reef…are helping the reef? Or helping Snorkel Bob’s bottom line?

As with many such emotional claims, there are nuggets of truth (albeit exaggerated) buried in what Snorkel Bob is saying. However, when examined skeptically, his conclusions seem flimsy and self-serving.

Do the Right Thing

Many hobbyists want to do ‘the right thing’ and buy sustainably caught animals for their tanks, but are continually frustrated by supporting projects only to find that they are not doing the noble work they set out to accomplish. Don’t despair. There really is good work being done out there, though it may be hard to see.

As collecting stations pop up marketing themselves as environmentally friendly, history shows us we must be skeptical even though we want to believe. Are they really doing what they say they are doing or are they are just using green speak to drum up more business?

Let’s look at one such operation: the SeaSmart project in Papua New Guinea. This project claims they are using all local labor, local ownership, safe collecting practices, and scientific survey techniques to determine how many of each animal can be collected without damaging the local environment. Are they for real? Here are several important pieces of evidence that indicate that SeaSmart may be giving us more that just lip service.

First, they have a track record of several years, which is longer than most other ‘green’ collecting stations, which tend to fold after a year or two. Second, the organization works closely with the government of Papua New Guinea, a nation that has a history of taking their natural resources seriously, protecting them, and educating their population on the reasons why those resources are important. Finally, and perhaps most encouragingly, SeaSmart is making an effort to be transparent to the consumer. The outfit uses social media, including Facebook, to continually post information, photos and video of the project. Previous attempts at sustainable collection had very little if any documentation, so it’s great to see SeaSmart putting that info out there on their own. SeaSmart even has an open door policy, so if you can get yourself to PNG, get in touch with these guys and they say they’ll be happy to show you first hand what they are doing. If you do go, please make sure to report back and share the information with other skeptical reefkeepers who would love to get behind a company that is doing good work.

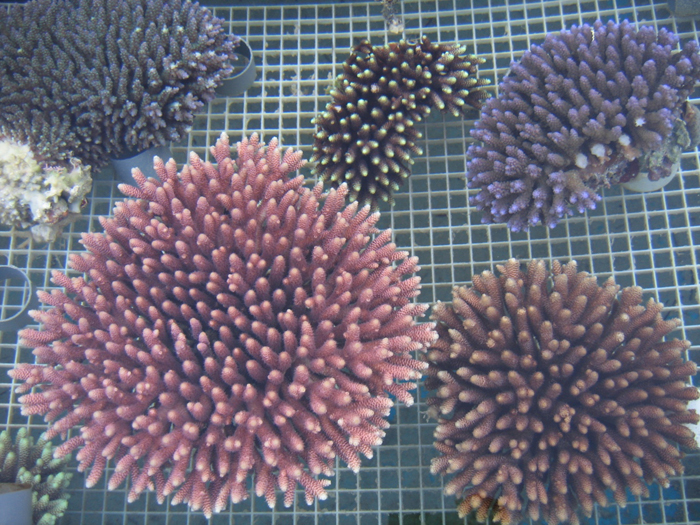

Freshly harvested wild acros. Corals of this size ship badly and remove a lot of coral from the wild which means its probably not a responsible collection practice.

If you keep asking questions, and digging when something doesn’t seem right to you, you are helping the hobby. You are helping to expose bad business, helping to save other hobbyists from wasting time or money on bad business, and most importantly, you are spreading the idea that good, sustainable work is wanted and important. You are also sending the message that empty promises will not be believed for long.

Next time

In the next installment we’ll explore the differences between captive bred, tank bred, tank raised, aquaculutured, and maricultured. Or maybe old reefers tales re-visitied. Or maybe we’ll look at electrical savings plans and see if they really save electricity. Or maybe…

Questions or comments – please start a thread on Manhattan Reefs or shoot me an Email at [email protected]

More about cyanide

http://www.wetwebmedia.com/cyanishart.htmhttp://reefkeeping.com/issues/2006-01/sp/index.php

Links, Further Readings and References

• http://homepages.wmich.edu/~korista/baloney.html

• http://www.nizkor.org/features/falla…dex.html#index

• http://www.skeptic.com/

• “The Demon Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark” by Carl Sagan, 1997 (Ballantine Books)

0 Comments