Before we get into the nuts and bolts of rearing marine fish in a closet, spare room or garage, there is some basic science and biology that one should know about the marine environment and marine fish reproduction. Most of us are more familiar with the reproductive biology of freshwater fish than marine fish. Nest making, protection of the spawn, mouth brooding by the male or female, and little fish hiding in weeds and rocks, being born and growing up in the same environment that the adults occupy are the natural order of things in fresh water and often, unless we have studied a bit of marine biology, this is the same scenario that we expect in the marine world. Although there are similarities, there are also major differences between the worlds of fresh and salt water, and these differences are very evident in the biology of the fish and invertebrates that occupy these environments.

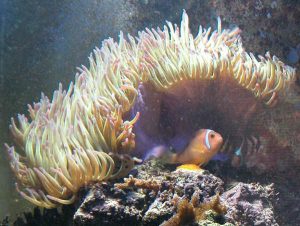

Clownfish are demersal spawners. This photo shows a female A. leucokranos depositing eggs on the liverock. The male waits nearby to fertilize the eggs. Photo: James Wiseman

Terminology

There are a few terms that you should know, and probably already do, that will make it easier to understand this article. The marine environment is made up of two major divisions, the pelagic zone, which is the water column from the surface to the bottom, and the benthic zone, which is the sea bottom and the structures that are part of the bottom. Plankton is a collective term for the mostly very tiny plants, phytoplankton, and animals, zooplankton, that float freely in both fresh and marine waters. These free-floating organisms are dependent on wind and tidal currents to move them about, thus they are pelagic organisms. Plants and animals that live on, in, and near the bottom are benthic or demersal, and are usually attached to, or live within or near, a benthic surface or structure, or a substrate. Many species of marine fish produce free floating pelagic eggs with no parental care of the eggs or larvae, and other species lay demersal eggs that are attached to a substrate and these species almost always care for the developing eggs.

A female banggai cardinalfish (_Pteragon kauderni_) releasing eggs to the soon to be mouth brooding male. Photo: saltwaterhobbyist.com

The larval stage of a fish’s life is that period between hatching from the egg and development of the physical characteristics typical of the juvenile stage. The larval stage may include a prolarval period that occurs right after hatching while the larvae is still developing eyes and other organ systems and is unable to swim or feed, and a postlarval period when the larvae is not yet physically a juvenile, but no longer feeds or lives as a larval fish. Metamorphosis is the transition between the larval and juvenile stage and may be a rapid overnight occurrence or may take several days of gradual physical change.

Early in elementary school we learn that there are boys and there are girls, and that there are very basic differences between the two. Not all fish, however, even though they may often be found in schools, have learned this lesson. Individuals of many species change their gender according to age, social standing, presence or absence of other males or females, and sometimes even just according to who spawned first. There are terms to describe these various sexual scenarios and if you are going to work with marine fish reproduction and propagation, you should know about them. The males and females of some species are genetically firm at birth and their sex does not change at any point in the life cycle. These fish are termed gonochoristic and the condition is gonochorism. Many species of marine fish are hermaphroditic, a condition where both sexes are present in the same individual. This can occur as sequential hermaphroditism, where male and female organs may mature in a single individual at different times in the life cycle, or as simultaneous hermaphroditism, where both sexes are mature at the same time in a single individual.

A male banggai cardinalfish (Pteragon kauderni) mouth brood a new batch of fry. Note the eyes peeking out of the mouth. This male has been holding for over 20 days. Photo: Adrian

The belted sandfish, Serranus subligarius, and the butter hamlet, Hypoplectrus unicolor, are examples of simultaneous hermaphrodites. Each individual can produce both eggs and sperm, but they always spawn with other individuals and produce either eggs or sperm according to the social interactions that occur before and during the daily spawning cycle. In some species, such as groupers, the female phase occurs first in the life cycle. These fish are known as protogynous hermaphrodites, and the condition is protogyny. When the male phase occurs first, as in clownfish, the fish are protandrous hermaphrodites, and the condition is protandry. Usually, once a sex change has occurred in a fish in either direction, it is apparently not reversible, but there is some evidence that suggests that a protogynous Pomacanthid angelfish, Genicanthus lamarck, reared in captivity from a juvenile may have begun the change from female to male, and then reverted back to female. Interestingly, some species of wrasses and parrotfish have primary males, which are born male, and secondary males, which become males after having been females. Some species of guppies, Poeciliidae, and silversides, Atherinidae, are all female, and produce eggs with a complete complement of genetic material and do not need to be fertilized, although sometimes a sperm from a related species is used to stimulate development.

Many fish species show sexual dimorphism, a condition where males and females are different in form and/or coloration thus the sexes can be distinguished externally. Perhaps the ultimate in sexual dimorphism occurs in the deep sea Ceratoid anglerfish. The female is basically a “solitary, floating, baited fish trap” while the male who found the female when he was still a juvenile, has attached onto her and soon becomes little more than a permanently joined parasitic appendage with well developed male sex organs. Those species that show only differences in coloration between the sexes are said to display sexual dichromatism, and others show no external characteristics that distinguish sex. The wrasses, Labridae, and the parrotfishes, Scaridae, are famous for their often very great sexual dichromatism, sometimes to the extent that males and females were initially described as different species. There are three classes of sexual morphism; monomorphic fish show no differences in form or color between the sexes. Fish that are temporarily dimorphic or dichromic show color differences in color and/or form during the breeding season or differences in color just during courtship and/or spawning. Permanently dimorphic or dichromic fish are always different in color and/or form. Sexuality in fish is quite complex and we still have a great deal to learn about sex and reproduction from fish, but knowing the above terms will be helpful in sorting out who is who, and what, and when, in the aquarium.

0 Comments