By Chris Jury

Introduction

Is it just me, or has the weather seemed a bit odd over the last few months? This winter the Washington D.C. area was hit by storm after storm, breaking its historic seasonal snowfall record (set back in 1899!), while Vancouver, B.C. had to truck in snow from several hours away to provide fodder for the Winter Olympics. It does seem awfully strange at first, but these are exactly the sorts of weather patterns that dominate when we have an El Niño in the Pacific, as we do now. During an El Niño most of the planet experiences warmer-than-average conditions (including much of Canada), but the Southern and Eastern U.S. gets cooler, wetter conditions due to temporary changes in atmospheric circulation. Cooler and wetter on the East Coast during the winter (along with an element of chance) gives us record snow in Washington D.C. while warmer gives us not much snow in Vancouver, B.C. It’s weird, but it happens.

Compounding the weirdness this winter, atmospheric circulation patterns between the Arctic and mid-latitudes (i.e., the Arctic Oscillation) shifted such that cold Arctic air rushed down into parts of North America, Europe, and Asia while warmer mid-latitude air shifted to the very far North. As I visited the East Coast this winter I was transported from balmy, luscious Hawai’i to far less balmy (though equally luscious) New York. Perhaps I could find respite in Florida? It has to be warm in Florida I thought, right? No such luck this year as that chilly Arctic air blasted its way all the way to South Florida…where some of the northernmost Atlantic coral reefs grow.

Thanks to the Florida current carrying warm Caribbean water northward, many of the deeper and outer reefs in the Florida tract remained at relatively normal winter-time temperatures (low to mid 70’s F). Many of the inshore and shallow reefs were hit hard by the cold though. At some sites temperatures dropped into the low 50’s and remained there for days. It will take time for a full assessment of the damage, but preliminary indications suggest that most of the corals in these areas were killed by the cold as were parrotfish, eels, and other reef denizens. Temperatures this low are far too low, and lethal for most coral reef organisms. Thankfully, low temperature anomalies like this in South Florida really are relatively rare, occurring perhaps a couple of times per century.

Thanks to the Florida current carrying warm Caribbean water northward, many of the deeper and outer reefs in the Florida tract remained at relatively normal winter-time temperatures (low to mid 70’s F). Many of the inshore and shallow reefs were hit hard by the cold though. At some sites temperatures dropped into the low 50’s and remained there for days. It will take time for a full assessment of the damage, but preliminary indications suggest that most of the corals in these areas were killed by the cold as were parrotfish, eels, and other reef denizens. Temperatures this low are far too low, and lethal for most coral reef organisms. Thankfully, low temperature anomalies like this in South Florida really are relatively rare, occurring perhaps a couple of times per century.

While the Eastern U.S., parts of Europe and Asia dealt with the cold, much of the planet experienced unseasonable warmth, including many of the world’s coral reefs. As the current El Niño has developed, temperatures have gotten quite hot indeed in some places. Many instances of coral bleaching (caused by high temperature stress, amongst other things) have been reported throughout the Indian Ocean thus far this year, and bleaching may be in store for reefs elsewhere depending on how conditions shape up as the Northern Hemisphere summer rolls in.

If we step back and look at the bigger picture we see that, in fact, unusually cold conditions are becoming less common on coral reefs while unusually hot conditions are becoming far more common. The Caribbean (in particular the Eastern Caribbean) experienced a very severe high temperature anomaly in the summer and fall of 2005. Temperatures from Puerto Rico through the Lesser Antilles made it to the upper 80’s and remained there for months. This heat stress brought about severe coral bleaching and mass coral mortality. Temperatures this high, clearly, are far too high, at least for most corals (reef fish are usually stressed at these temperatures as well).

Temperature is a critical parameter in our tanks. Everything that happens in our aquaria, from rates of fish and coral growth to microbial nutrient processing, depends strongly on temperature. If temperature is wrong, then it doesn’t particularly matter if anything else is right. Without a doubt there is such a thing as too high and such a thing as too low when it comes to temperature in our reef tanks. Neither is necessarily better than the other as both will cause harm. I don’t think I’ll raise many objections if I say that the 50’s F is too cold for our reef tanks and the high 80’s F is too hot, but what should we shoot for between these extremes?

There has been much discussion about the best temperatures for reef tanks in recent years. In 1997 Dr. Ron Shimek wrote,

The average annual temperature of most coral reefs is around 82 to 84 degrees Fahrenheit (27 to 28 degrees Celsius),[sic] which seems to be the optimum for coral growth. The commonly advised mini-reef temperatures of 74 to 77 degrees Fahrenheit (22 to 25 degrees Celsius) are stressing most of the animals unnecessarily and, in some cases, severely.

In response to these suggestions Richard Harker replied,

The commonly recommended reef tank temperature range of 74 to 77 degrees Fahrenheit (23 to 25 degrees Celsius) is well within the temperature range in which healthy reproducing corals thrive.…hobbyists would be wise to maintain their reef tanks at the mid-point temperature of coral reefs, approximately 79 degrees Fahrenheit (26 degrees Celsius).

In 2002 Charles Delbeek wrote,

In 2002 Charles Delbeek wrote,

Put simply, water temperatures at or above 82 degrees Fahrenheit will eventually result in system problems. The desired temperature range is somewhere between 75 and 80 degrees.

Delbeek and Sprung concurred in 2005,

The temperature in reef aquariums should be maintained between 22-27°C (72-80°F) for the best results, and kept as stable as possible. In our experience, the center of this temperature range, 23-25°C (74-78°F), is ideal.

While in 2009 Dr. Ron Shimek reiterated,

…[I] recommend warmer water temperatures, at least 82 [°F] for good health…

So then, there you have it. It’s all very clear what we should be doing, isn’t it? Sure, clear in the same way that mud is clear. Reading such conflicting recommendations from these highly talented aquarists and prolific authors, it can be difficult to know what to do, where to begin, or even what to consider in making a decision. We might call this ongoing discussion the Great Temperature Debacle …I mean, Debate.

In this article I’d like to begin to reexamine how we as aquarists decide where to maintain the temperature in our reef tanks. This is a multifaceted and important topic and I have therefore decided to split it into (at least) two articles, to allow for fuller discussion. My purpose is not to tell the aquarist what to do in his or her own tank—I leave it to the aquarist to decide if my recommendations seem like a good fit—but rather to develop the criteria upon which individual aquarists can make their own decisions about what to do with their tanks. Further, I do not intend these articles as the last word on the subject. Indeed they decidedly should not be the last word since our understanding of temperature effects on diverse aspects of reef organism physiology and reef aquarium husbandry continue to expand. Rather, I hope that these ideas will prove useful to the average aquarist and encourage careful, critical evaluation of not only how by why each of us elects a particular regime for our tanks.

Does Mother Nature Know Best?

Be careful about placing too much faith in Mother Nature—she’s a horrible tease.

It is quite common amongst aquarists when discussing all sorts of aspects of reef tank husbandry to defer to Mother Nature. The clear assumption here is that whatever is natural—normal, as it were—is probably also ideal. Let us consider this assumption for a moment. The cold snap that wrecked havoc on some Floridean reefs this winter was perfectly natural. Hurricane Allen, which leveled many of the reefs on Jamaica’s north shore, was perfectly natural. Extreme low tides, Crown-of-thorns starfish predation, tsunamis, and myriad other seriously damaging phenomenon are all natural on coral reefs. We don’t want to replicate these things.

It’s not necessarily the case that Mother Nature knows best but rather that Mother Nature is simply good enough. If a sufficient number of coral, invertebrate, and fish larvae settle and survive on damaged Floridean reefs then they will ultimately recover from natural disturbances, as they have repeatedly over the last several thousand years. If not then those reefs will eventually collapse, just as countless fossil reefs within the Florida reef tract have. What Floridean reefs experience is not necessarily the ideal situation for many of the organisms that live there, but rather the conditions are simply good enough for long enough to allow some reef development before everything gets knocked back again. Make no mistake though, Florida is full of reefs that were once spectacular and are now long dead.

It’s not necessarily the case that Mother Nature knows best but rather that Mother Nature is simply good enough. If a sufficient number of coral, invertebrate, and fish larvae settle and survive on damaged Floridean reefs then they will ultimately recover from natural disturbances, as they have repeatedly over the last several thousand years. If not then those reefs will eventually collapse, just as countless fossil reefs within the Florida reef tract have. What Floridean reefs experience is not necessarily the ideal situation for many of the organisms that live there, but rather the conditions are simply good enough for long enough to allow some reef development before everything gets knocked back again. Make no mistake though, Florida is full of reefs that were once spectacular and are now long dead.

The one thing we can say about the conditions that Mother Nature provides is that they seem to work well enough, even if they are not ideal. When there is no clear benefit from providing conditions different from those provided in nature it is my suggestion that it is probably best to mimic nature as closely as we can simply because we know that should more-or-less work. Sometimes there are indeed good reasons to avoid mimicking nature in captivity though. Clear examples would be in avoiding letting our tanks drop into the 50’s F, or avoiding coral predators. There may be good reasons to provide temperatures a tad different in our aquaria than what is typical in nature, but before we consider those reasons let’s examine what sorts of temperatures tropical coral reef areas experience in nature.

Coral Reef Temperatures

The temperature on a coral reef is not constant, nor is the range of temperatures experienced the same on different reefs. Defining what typical coral reef temperatures are, therefore, is difficult, and perhaps not entirely meaningful. What is typical for one reef may be decidedly hot or cold for a different reef in a different region. To get some sense of the degree of variation from one reef to another, as well as the seasonal variability on an individual reef let’s consider a few examples. For this exercise I’ve utilized data available through the NOAA Coral Reef Watch program (these data can be accessed here). These temperature data are measured with the Pathfinder satellite and are monitored as part of the Coral Bleaching Virtual Station program. For each of these stations I’ve included the average (climatological) temperatures over the annual cycle as well as measured temperatures for 2009, to give some sense of the degree of interannual variability.

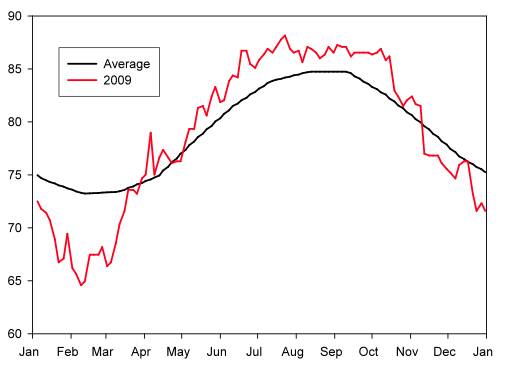

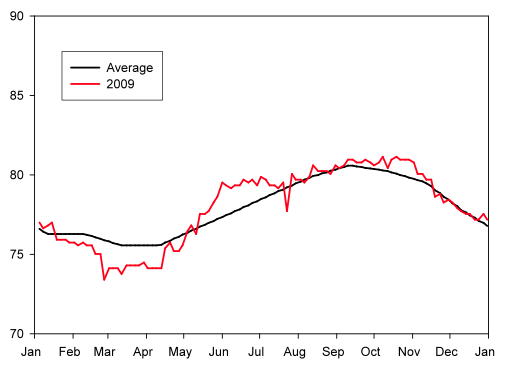

In Figure 1 the temperature data are plotted for Sombrero Reef, a well-developed reef about mid-way up the Florida Keys. As we can see, there’s quite a bit of seasonality at this reef. Winter temperatures are relatively cool, averaging in the low to mid 70’s F, while the summer is warmer, averaging in the mid 80’s F. In 2009 the annual temperature range was wider than the average range, dropping to the mid 60’s for part of the winter and climbing to the mid to upper 80’s during the summer. Both high and low extremes can prove stressful to corals and other reef organisms.

Figure 1. Sea-surface temperature measured at Sombrero Reef, FL as part of the Coral Bleaching Virtual Station program through NOAA. Climatological average temperature (black) and recorded temperature for the year 2009 (red).

Most people aren’t likely to keep too many Floridean reef denizens in their own reef tank, but the range of temperatures (both high and low) we see in the Florida reef tract sandwiches the range we typically see on most other reefs.

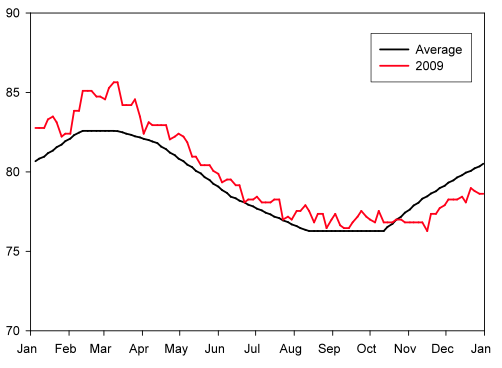

If we move over toward my neck of the woods and examine the Oahu-Maui, HI station we see much less seasonal variation (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Sea-surface temperature measured at Oahu-Maui, HI as part of the Coral Bleaching Virtual Station program through NOAA. Climatological average temperature (black) and recorded temperature for the year 2009 (red).

Compare these data to those at Sombrero Reef, FL (but note the difference in scale). Average winter temperatures in Hawai’i drop near the mid 70’s but then only rise to the low 80’s during the summer. Temperatures tend to be less variable around these means than in Florida as well, due in large part to the moderating effects of the massive Pacific Ocean that surrounds us here in Hawai’i. The hobby doesn’t get corals from Hawai’i, but a lot of reef fish and some invertebrates are collected in Hawaiian waters.

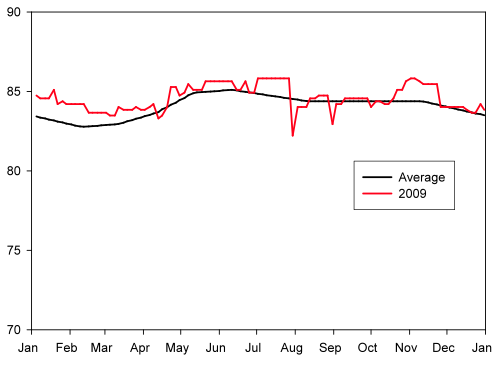

One place a lot of corals in the hobby do come from is Fiji, and we turn our attention to the Fiji-Beqa station next (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Sea-surface temperature measured at Fiji-Beqa, Fiji as part of the Coral Bleaching Virtual Station program through NOAA. Climatological average temperature (black) and recorded temperature for the year 2009 (red).

Like in Hawai’i, the annual temperature variation in Fiji is much less than in Florida. Temperatures near Fiji typically average a few degrees warmer than in Hawai’i—the upper 70’s in winter and the low to mid 80’s during summer. As can be seen above, 2009 was mostly warmer than average near Fiji, in keeping with the record warmth the Southern Hemisphere experienced last year (hottest year on record).

Last, I’ve included data for the Palau station in the Coral Triangle, a hotspot of biodiversity for corals, reef fish, reef invertebrates, and many other organisms. This area, in keeping with most of the Coral Triangle and the Western Pacific Warm Pool is warm, warm, and warm (Figure 4). The summers are typically in the mid 80’s and temperatures drop all the way down to the low to mid 80’s in winter…brrrr. There is clear seasonality even in Palau, though temperature doesn’t vary that much seasonally. Many corals, fish, and invertebrates we might keep in our tanks are collected in areas with a climate like that of Palau.

Figure 4. Sea-surface temperature measured at Palau as part of the Coral Bleaching Virtual Station program through NOAA. Climatological average temperature (black) and recorded temperature for the year 2009 (red).

Conclusion

Temperature is a critical parameter on coral reefs, and in our reef tanks. The sort of temperature range most appropriate for reef tanks in captivity has sparked intense debate amongst aquarists for years. Without clear reasons to deviate from what Mother Nature provides, it is often wise to replicate the natural state as closely as possible, but keeping in mind that simply because a condition is natural does not mean it is ideal. Temperature varies interannually, seasonally, and over finer time scales on coral reefs. Here we’ve examined the seasonal variation in temperature in four representative reef areas, and used temperature data from 2009 to get some sense of the degree of interannual variability. Sombrero Reef in Florida experiences a wide range in annual temperature—from the low 70’s to the mid 80’s, on average, and can certainly experience a larger range in any given year. Palau, on the other hand, experiences a much smaller seasonal range—only within the low to mid 80’s, on average. While these temperatures are natural, there can be good reasons to deviate from what nature provides. We’ll discuss some of these reasons in the next issue. The temperature ranges quoted here don’t tell the whole story either. Actually, as we’ll see, averages lie.

References

Delbeek, J.C. 2002. Your first reef aquarium. Aquarium USA, 2002 Annual.

Delbeek, J.C., and Sprung, J. 2005. The Reef Aquarium: A Comprehensive Guide to the

Identification and Care of Tropical Marine Invertebrates. Vol. 3: Science, Art and

Technology. 680 pp. Ricordea Publ. Coconut Grove, FL

Harker, R. 1997. Reef tank temperatures—another view. Aquarium Frontiers Magazine.

Shimek, R. 1997. Natural reef salinities and temperatures. Aquarium Frontiers Magazine.

Shimek, R. 2009. Response in answer to the question “What has changed?” with regard to reef tank husbandry recommendations since 2004-2005 (access here).

0 Comments