By Todd Gardner

Atlantis Marine World is a small public aquarium on the East end of Long Island, New York. Its small size is belied by a growing reputation in the aquarium world, fueled largely by its crown jewel, a 20,000-gallon living coral reef tank, created and maintained by curator and co-founder, Joe Yaiullo.

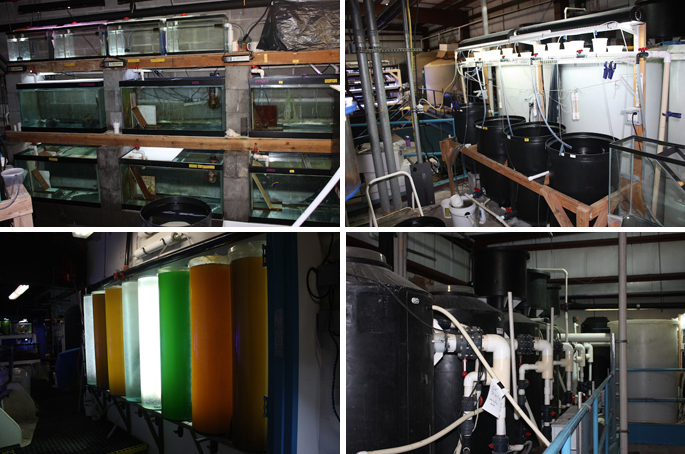

As in any public aquarium, there is probably more going on behind the scenes at Atlantis than there is out on the display side of the tanks – at least more that would be of interest to an aquarium addict. Sumps, filtration, lighting, quarantine and holding systems, miles of PVC, food storage and preparation areas -essentially, everything needed to support our exhibits. However, what makes the biggest splash on our behind-the-scenes tours and what makes my job worth getting out of bed for every morning are the little projects we have squeezed into every bit of available space around the facility.

It’s not easy living on an aquarist’s salary, especially in New York, which is why we all have second jobs and why there is generally a high turnover rate in the field, but one of the secrets to Joe’s success in keeping employees is this simple rule: as long as our tanks look great and there is nothing urgent that needs our attention, we can spend as much time as we want on our projects behind the scenes. Of course they need to be at least superficially relevant and if they benefit the aquarium directly, then we might even get a pat on the back in the form of, well, a pat on the back. The projects I’m talking about are mostly related to aquaculture and we’ve built a number of systems for housing breeding pairs of fishes and invertebrates as well as for rearing their offspring.

clockwise from top left: Broodstock system for anemonefishes and damselfishes.; Quarantine and holding systems; Protein skimmers for our shark tank (constructed in-house); Algae culture tanks.

I think what initially sold Joe on the idea of hiring me was my aquaculture background. The thing that sold me on the idea of working here was an evening I spent with Joe and senior aquarist, Chris Paparo in front of the big reef tank almost 10 years ago. As we stood there, mesmerized, the lights on the tank started to dim and before long we started seeing groups of tangs, pygmy angels, and wrasses shooting to the surface, releasing their gametes in what can only be described as a spawning orgy. I think the same thing occurred to all of us: it sure would be nice to take advantage of all the spawning going on around here.

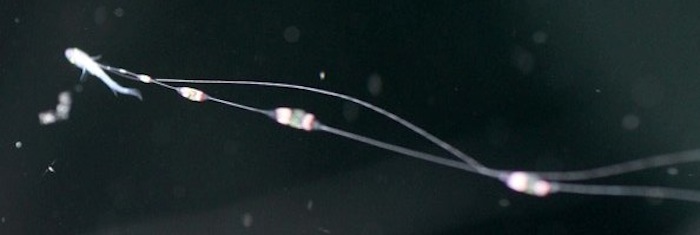

We are constantly working on techniques for removing pelagic eggs and larvae from the reef tank before the Chromis, Anthias, and flasher wrasses can eat them. They seem to know when their tank mates are close to spawning and they stay very alert, then dive right in as soon as the spawn is released. Like seniors lined up at the early bird buffet, most reef fishes detest the thought of missing out on a cheap meal, and I guess fresh eggs taste a lot better than flakes, pellets, and frozen mysids. We’ve tried egg collectors on the outflow of the tank, but very few eggs make it that far. We’ve also tried standing on top of the tank with a fine-meshed net waiting to scoop up the eggs from the water column, which has been moderately successful, however, it’s not easy to be perched up there without distracting the fishes from spawning. They are quick to stop what they’re doing at the sight of the hand that feeds them. We have however, had good success removing benthic spawns from the reef tank and other displays. If a pair of fish is spawning in a difficult spot like on a large rock, we try to place a piece of tile in the vicinity in hopes of enticing them to spawn on a nice, smooth, clean, and most importantly, removable surface. Broodstock tanks for seahorses, anemone fishes, gobies, and other assorted small reef species help keep our rearing systems active throughout most of the year.

Our clownfish broodstock system consists of six 50-gallon tanks with a five-gallon bio filter containing plastic bio balls and a 40-watt UV sterilizer. Each tank contains a pair of fish and a structure made from four tiles that doubles as a shelter and a surface on which to spawn.

Another system consists of a line of 29-gallon tanks devoted to pairs of small, challenging reef species. As much fun as it is to pump out tanks full of anemonefishes and seahorses, the thrill of working on some of the more difficult species helps to keep our level of interest high and our culture skills sharp; otherwise fish culture runs the risk of becoming just a job.

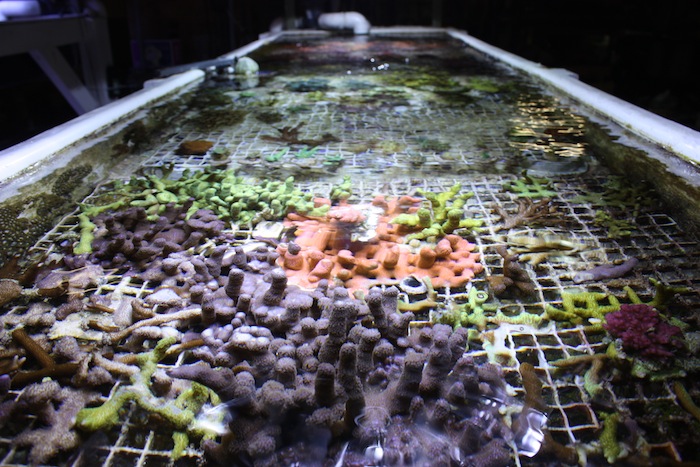

Culturing new and difficult marine species has always been a passion of mine, and the rest of the gang here seems to have caught that bug too. In addition to working with me on all of my projects, Chris Paparo also maintains our coral propagation system. When it’s not causing him to pull his hair out, that system, composed of long, shallow troughs provides enough coral frags to make us a lot of friends in the world of public aquaria and coral researchers, as well as helping to foot the bill for coffee and donuts at all the local reef club meetings. Our newest aquarist, Allison Petty, a self-proclaimed Ceph Head, has had tremendous success raising cuttlefish and has recently seized an opportunity to raise a brood of flamboyant cuttlefish,Metasepia pfefferi, enabling Atlantis Marine World to be the first aquarium in the US (and possibly, the world), to exhibit tank-raised specimens of this species.

During late summer and early fall, we slow down aquaculture production in order to devote more time to collecting tropical fish species that stray into our waters, courtesy of one of the world’s most powerful ocean currents, the Gulf Stream. That shift of attention also frees up tank space for quarantining and growing out these wayward fishes until they can be put on display or traded off to the wholesaler or other public aquaria. I’ll have more about that in a future article.

top: Seining for tropicals in Shinnecock Bay.

bottom: A nice haul of spotfin butterflyfish, Chaetodon ocellatus.

In November when the ocean water cools and the last of the tropicals have been caught or fallen victim to the cold, we are ready to jump back into aquaculture with renewed vigor. This seasonal variation in attention, alternating between aquaculture and diving and seining for tropical species keeps life interesting and really makes the time fly. When I first started working at Atlantis Marine World, it was my intention to be here for no more than a year, just to help pay the bills while I finished up revisions on my Master’s thesis. Then I was going to get myself into a PhD program or back into commercial aquaculture somewhere, as far away from New York as possible; but here I am, almost ten years later, looking forward to getting up tomorrow morning so I can go in and keep chipping away at the latest challenge: to get Liopropoma larvae beyond my previous rearing record of 46 days.

Although our primary objective is not fish production, and we are certainly not in the business of selling marine fishes, we don’t have a problem with taking our surplus to the local wholesaler for a little fish bartering. It’s great to go in there with a couple of boxes of our captive-bred fish and have the ability to go on a $1000 shopping spree for new display specimens and broodstock pairs without raising the eyebrows of our accountants. I am often asked if all of this fish trading really pays off. We certainly don’t eliminate the need to spend money on fishes and invertebrates, but, is the time and money we spend to produce these animals justified by our savings at the wholesaler? I seriously doubt it. Especially if you figure in the labor involved; however, it’s difficult to put a price on the benefits gained by permitting aquarists to take on these challenges while contributing to the advancement of aquaculture through articles and presentations about their work.

All photos by Todd Gardner except where indicated.

0 Comments