In my 50 years as a marine biologist and culturist of marine fish (and a few invertebrates), I have written a number of books, articles, and scientific papers. Some of these are both historically interesting and still have descriptive value for the culture of various species. I plan to revisit a few of these in Advanced Aquarist from time to time in a series titled “The Way We Were”.

This is an article from the dawn of marine fish culture. It appeared in the February 1975 issue of The Marine Aquarist. It was titled “Propagating the Atlantic Neon Goby” and it described the first successful efforts at mass culture of the neon goby, Elacatinus oceanops formerly Gobiosoma oceanops. The photos are in black and white, the only color for small magazines back in those days, when color was very expensive, was on the cover. An inside color photo was very rare. The photos in my original article were good for the time but are now only of historical interest. There is a new thing called the internet, I believe, that has amazing and wonderful photos of gobies and the entire process of breeding them that I could not even imagine back in the 70s, so now the information on breeding this goby is available at the click of a mouse (a phrase which would have a very different meaning back in the 70s).

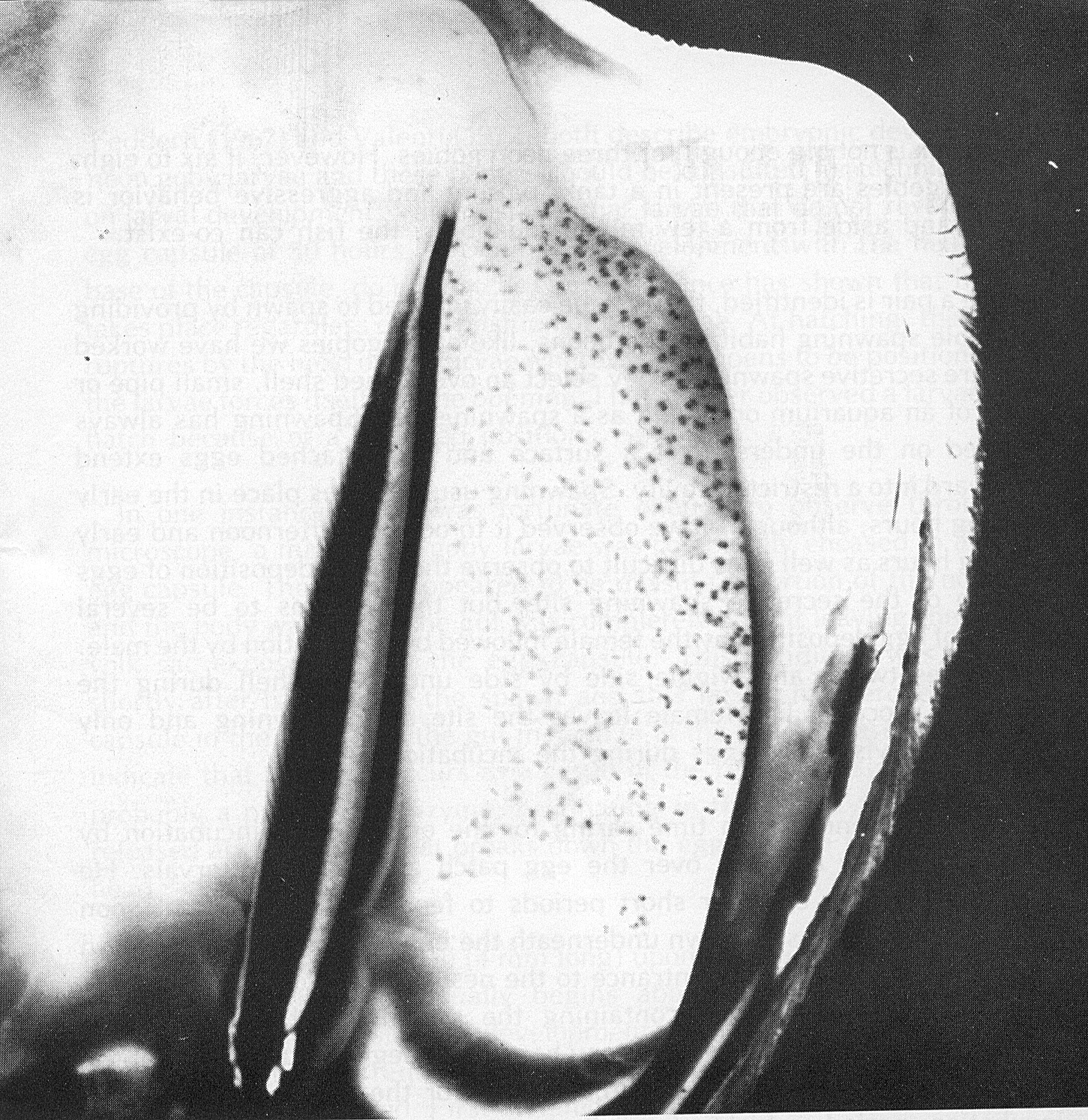

The male neon goby guards the eggs and aerates the developing embryos.

I selected the neon goby as the second species to breed after the false clownfish, Amprhipion ocellaris, because of its great popularity, importance and value as a parasite picker in nature and in captivity, and its interesting and easily observable behavior in aquariums. It turned out to be relatively easy to breed, its small size, compatibility of mated pairs, frequency of spawning, and the ability of the larvae to begin feeding on rotifers made it a very good species for culture. The only drawback, especially back in the mid 70s, was the low price. Times have changed but popularity of the neon goby, an excellent species for reefs tanks and fish only tanks, is still very strong. We spawned and reared several other species of gobies and were most successful with the sharknose goby, Elacatinus evelynae, and the Christmas or Greenbanded goby, Gobiosoma multifasciatum. At that time only the neon goby was popular enough to support commercial production. The greenbanded goby was also a bit more difficult to rear because the larvae required a bit smaller rotifer than was available at that time and so early feeding depended on providing only the smallest of rotifers, which was a bit problematic.

Even now, as then, the popularity of a species with consideration of availability and price of wild caught specimens, determines whether or not commercial production at any level is worth the effort and expense of breeding. But fortunately, these gobys and a number of others are now captive bred and available to aquarists.

Published February 1975 issue of The Marine Aquarist

Propagating the Atlantic Neon Goby

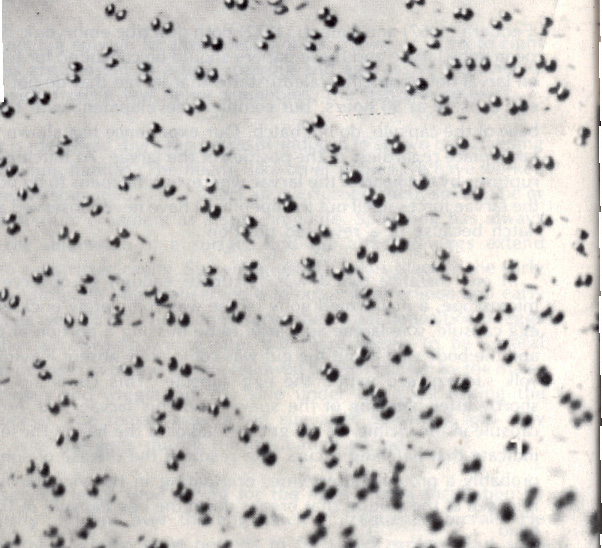

A close up of neon goby eggs after 7 days of incubation. The eggs hatched soon after the photograph was taken .

The neon goby, Gobiosoma oceanops, is one of the largest species of the genus and probably the most common go by in marine aquariums. It is a cleaner species and even though of small size (2 to 3 inches as adults) the neon goby does well in a community tank. It will engage in cleaning behavior with Pacific as well as Atlantic marine fishes. We often keep them with large clownfish and frequently observe symbiotic cleaning behavior. The clownfish assumes a head up position and slowly flutters its fins while the neon goby swims with rapid, jerky movements over the clownfish’s sides and fins looking for parasites. A quick shake and resumption of normal swimming posture by the clownfish breaks the cleaning pattern and sends the goby on its way. The neon and its close relative, the shark-nosed or gold lined goby, Gobiosoma evelynae, make an interesting and colorful addition to any marine tank and even benefit the occupants through their parasite cleaning behavior.

As the neon gobies mature, they begin to pair for mating and can cause great problems In the close confines of an aquarium. Once a pair is established they forcibly reject any others of their species and even a 100-gallon tank is not big enough for three neon gobies. However, if six to eight or more gobies are present in a tank, pairing and aggressive behavior is muted, and aside from a few minor squabbles, the fish can co-exist.

Once a pair is identified, they can be easily induced to spawn by providing a suitable spawning habitat. The neons, like other gobies we have worked with, are secretive spawners. They select an overturned shell, small pipe or inside of an aquarium ornament as a spawning site. Spawning has always occurred on the underside of a surface and the attached eggs extend downward into a restricted cavity. Spawning usually takes place in the early morning hours, although I have observed it to occur in afternoon and early evening hours as well. It is difficult to observe the actual deposition of eggs because of the secretive spawning site, but there seems to be several periods of egg deposition by the female followed by fertilization by the male. Both sexes twitch and wiggle side by side under the shell during the spawning process. The female leaves the site after spawning and only infrequently visits the eggs during the incubation period.

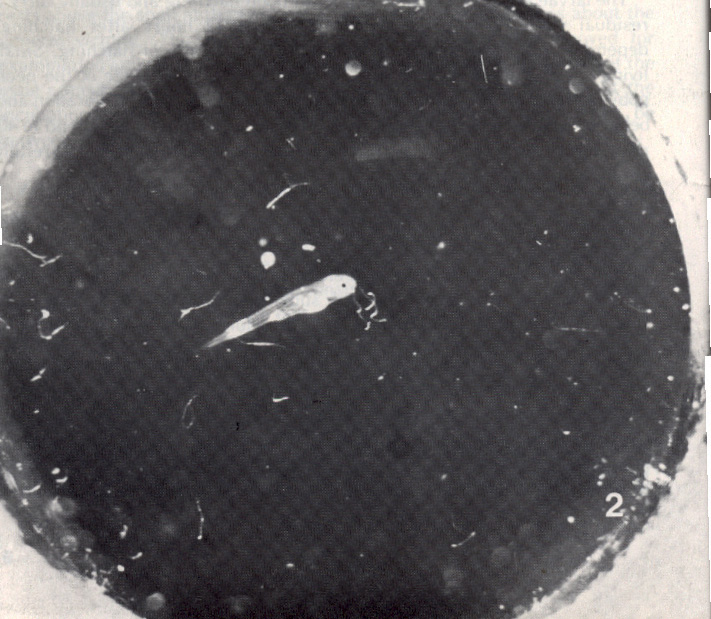

A newly hatched neon goby larvae. The larvae is only 4 mm long and still retains a noticable yolk sac.

The male spends much time caring for the eggs during incubation by moving his body and fins over the egg patch at frequent intervals. He readily leaves the eggs for short periods to feed and explore, but soon returns and rests upside down underneath the egg mass. The female often rests above the shell at the entrance to the nest cavity or cruises about the general vicinity. The shell containing the spawn can be removed for examination and replaced without any harm to the eggs or disruption of the male’s incubation behavior. The male cares for the eggs throughout the incubation period, which, depending upon the temperature, may be between 6 to 8 days.

A large female at the height of reproductive activity may lay 500 to 600 eggs, but the usual spawn size is about 250 eggs. The egg capsule is about 2 mm long and 1 mm in diameter and is completely transparent. The entire development of the embryo can be observed through the chorion, or egg case. The attachment of the egg consists of a mass of fiberous threads extending from the base of the egg capsule to a sticky pad that adheres to the substrate. The eggs are placed very close to each other and the newly laid spawn has the appearance of-an undulating patch of clear globules. After the eyes become pigmented, the patch takes on a silvery appearance. The embryo begins development with the head pointed towards the base or attached end of the egg capsule. The embryo turns around in the egg capsule on about the third day of development and completes incubation with the head developing within the stelate, distal end of the capsule.

Feddern (1967) and Valenti (1972) both describe embryonic development of neon goby larvae and these papers should be consulted for technical details on larval development. Valenti states that larvae that do not reverse in the egg capsule at 50 hours, but complete development with the head at the base of the capsule, do not hatch. Our experience has shown that hatching takes place regardless of the position of the larvae. At hatching, the capsule ruptures by the head of the larvae wherever it happens to be positioned, and the larvae forces itself out the opening. I have never observed a larvae fail to hatch because of a reversed position.

In one instance that I was fortunate enough to observe through the microscope, a malformed goby larvae was completely encased in a normal egg capsule. The larvae appeared to be missing a portion of the notochord and the body wall about the gut was completely absent leaving the gut and yolk sac exposed within the egg capsule. This condition was observed shortly after hatching of the spawn and this larvae had eroded the egg capsule in the vicinity of the gut instead of at the head. These observations indicate that hatching occurs as a result of the release of some substance, probably a proteolytic enzyme, originating in the vicinity of the gut and released at the mouth that breaks down the egg capsule in the area of the head.

Tank reared neon gobies about 2 months old. These fish are the result of two separate spawns that were reared together.

The larvae are quite small (4 mm long) upon hatching and usually carry a residual yolk. Feeding usually begins about 12 hours after hatching, depending upon the state of development at the time of hatching. Small living organisms are required as a first food. The larval stage of the neon goby is rather prolonged. First metamorphosis into the adult coloration and behavior pattern occurs at about 18 to 20 days, although it may extend to 40 days under adverse conditions. The larvae are reared under a carefully simulated pelagic environment.

The early juveniles take up a benthic mode of life shortly after the first color appears on the transparent larvae. A faint blackening of the sides quickly becomes a bright sliver of electric blue and the cupped pelvic fins attach the early juvenile to the tank substrate. Growth is rapid after this point in development is attained and sub-adult size is reached within 3 months. The young gobies can be paired at this time although first spawning is still 2 or 3 months in the future.

We have spawned about ten pairs of tank reared gobies to date and have noted no obvious difference between wild and tank reared fish, either in morphology or reproductive success. Growth continues after spawning commences and when the fish are ten months to a year old, they are full adult size and are at the height of reproductive activity. Spawning takes place every 10 to 12 days depending on temperature, and we have had pairs spawning in every month of the year. The spawning period in nature is February to April (Feddern); however, we have been able to spawn the gobies every month of the year in the laboratory.

References

- Feddern, H.A.1967. “Larval Development of the Neon Goby, Elacatinus oceanops, in Florida,’ Bulletin of Marine Science, Vol. 17, No.2, pp. 367-375.

- Valenti, R.j .1972. “The Embryology of the Neon Goby, Gobiosoma oceanops,” Copeia, 1972, No.3, pp. 477-482.

0 Comments