By Simon Garratt

If you have ever seen the film ‘Final Destination’ you will appreciate what I’m about to say. Running a reef tank can be like playing tag with the Grim Reaper. No matter how many times you dodge the metaphorical bullet, sooner or later he’s gonna catch you, and if he can’t get ‘you’, then he will sure as hell get your stock. Try as you might to outwit, and try as you might to foresee all ways in which you can be caught out, he will always find some inexorable way to come at you from the least expected angle. And if he still misses, then his brother Murphy will step in to take up the slack.

Or to put it in plain terms;

Murphy’s law: If anything can go wrong, it will. If there is a possibility of several things going wrong, the one that will cause the most damage will be the one to go wrong. If you perceive that there are four possible ways in which something can go wrong, and circumvent these, then a fifth way, unprepared for, will promptly develop. It will be impossible to fix the fifth fault, without breaking the fix on one or more of the others.

That in essence is the darker side of reef keeping, and no matter how long you’ve been in the hobby, or how good you are at running a reef tank, sooner or later you will fall foul of one of the above clauses within that law. When you think about this, it isn’t that surprising. We run systems that are amalgamations of several different principles, we combine opposing forces like water and electricity in the hope that they will never combine in a detrimental manner. We run a whole host of equipment, each crucial in maintaining either a single or multiple aspects of the miniature ecosystems we create, whilst all the time trying to control a small volume of water that is home to a veritable soup of interacting molecules that we try to count and quantify as though we were sorting grains of sand on a beach.

Sometimes the failures are clear and easy to diagnose with varying results from minor to catastrophic. Sometimes they are less so and creep up on you until you are either lucky and find the cause before too much damage is done, or you have to cut your losses and take drastic action. Sadly over the course of July to September this year, I suffered the latter.

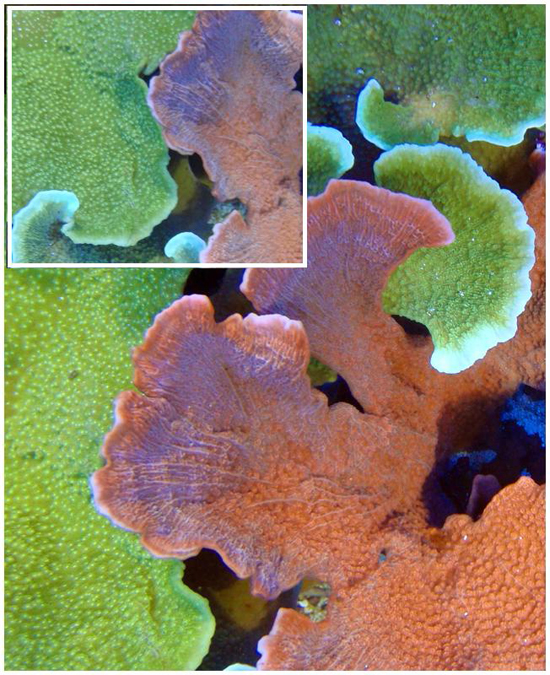

Initially, I considered a slight down turn in certain corals as just one of those phases that all tanks go through where the normal ebb and flow of system age and maturity affects things to differing degrees. Tied with the fact I was traveling quite a bit at the time, it wasn’t one of those things I was able to keep monitoring on a daily basis, so the tank was left pretty much to its own devices after running a set of standard tests with nothing unusual showing up. A few weeks later after returning from a trip to Europe which admittedly included a very hot spell, I was quite shocked to come home to a tank rife with cyanobacteria, several bleached, but otherwise intact corals, and a fish population none-the-worse for wear. So, after a further set of tests which still showed no adverse levels, I put the bleaching incident down to a short term temperature spike and the cyano down to dissolution of nutrients from the substrates in the high temperatures mixed with a slightly suppressed pH. So, as all good keepers would do, I changed the GFO, changed the carbon, and did a few 25 gallon water changes on my 400 gallon system. Off I set again on another trip only to return to a tank which was considerably worse than before. With more bleached corals, several corals dying off from the center and bases outwards and a cyanobacteria bloom which was still unnerving in its tenacity.

Despite the grim look of the tank, the fish were still in perfect health, so after doing a full set of tests covering all the usual suspects (Nitrate, Phosphate, Magnesium, Calcium, Alkalinity, Iodine, and Strontium) and double checking pH and temperature probes, it was indeed time to ***** up the ears and start thinking of something that was outside the normal ranges. The first port of call in most cases is to have a look at the top up and test the TDS; this gave a zero, so I knew the top up water was fine. Then it was then time to go through the system looking for any other contamination from foreign materials. Scraper blades, water storage containers leaching toxins, pump impellers corroding, magnets leaking and leaching, calcium reactor media that has got foreign material in it by accident etc. A pretty exhaustive list was executed which basically went through the entire system from top to bottom to no avail.

After performing a few more water changes a few days later and seeing the results of those changes, it became evident that the more I tried to clear up the problem via dilution, the worse the problem got. So my attention switched back to the top up and change water again. Whether it’s based on experience, instinct, or some other influence, I kept going back to that TDS meter. It was no surprise that after doing a quick test on differing solutions that all showed zero on the TDS readout, it became clear that the meter was faulty. Not only that, but on replacement with a new one, I realized that one of the RO membranes had failed, letting pure tap water past the main seal. My DI resin was saturated, and the tank was being topped up with water that had a final TDS output of over 168ppm, and had been for some time.

My 400 gallon system evaporates on average 4-5 gallons a day due to running several fans, room ventilation and metal halides in a relatively tight space. So after some basic maths and considering the 3 month period since the issues had started, it became clear that over that period, I’d basically added over 400 gallons in contaminated top up, whilst only performing at best 100 gallons in water changes, and even that was contaminated!

It was at that point after looking at the amount of damage evident on the corals, and working out the real world possibilities of pulling the system around in time before a total loss of coral stock was involved, that the decision to drain the system down and transfer remaining stock to a holding system was made. I also decided to include a failsafe system to avoid the issue happening again. So, I added a second TDS meter to confirm any reading on the first, and a second inline DI pod that would take up the slack as soon as the first was spent if I was away on business.

Filling a trailer full of contaminated rock, and buckets of dead coral is not a nice way to spend a Saturday morning.

There can be little more depressing from a reefkeeper’s point of view than pulling out buckets of dead or dying corals. And whilst we can take solace in the fact that we can often save a few frags from our colonies if we catch things early enough, it still doesn’t detract from the heartache it causes, not only from a personal perspective, but from the livestock’s as well. Passionate as we are, the hardest thing to deal with in most cases is the suffering or stress that any stock goes through during the process.

Once all is said and done, its easy to look back in hindsight and kick yourself for making a silly mistake or not seeing a fundamental weak spot in the system. But take heart, the best of us make these mistakes, and we always will to varying degrees. The main aim is to learn from these experiences, correct the flaws in our methodologies and above all else share this information with others so that they may be able to avoid the same issues and heartache. There is no shame in getting it wrong as long as the mistake isn’t through laziness, cutting corners, or ignoring a glaring risk. Just remember that Murphy is a very smart guy who is constantly trying to catch you out in the most inventive way he can find. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to avoid him and preempt those attempts.

So what is the lesson here? Well, it is two-fold:

First, never trust a digital monitor a hundred percent. Admittedly, they are more reliable than test kits, but they are not infallible by any means. They can lie, so a backup or at least access to a backup is always advisory once all other avenues have been exhausted.

Second, take a moment to think about your own system. Our biggest challenge as reefkeepers is to balance what goes in our systems as well as what comes out so we can maintain a stable environment. How many times have you looked at your TDS meter and spotted a 1 or 2 ppm reading and thought, “That’s not so bad, I’ll change the DI resin this weekend”, only for it to go another week beyond that due to other commitments. What we often forget when running systems, especially those that use evaporative cooling, is the sheer volume of water that goes into our systems over the course of a year or two or three, compared to what we remove in water changes. It’s often the case that we may be looking at a huge difference between what goes in, compared to what we take out, especially if what goes in is even minimally contaminated with materials that can’t be removed by other means.

It may well be (in the absence of more advanced testing methods) that many cases of what we term “old tank syndrome” may simply be an accumulation of undesirable contaminants that make their way in via various pathways, building up over time until they finally reach a point where their effects are felt on a larger scale, be that directly in the stock, or more insidiously working in the background to hinder biological activity and the systems ability to maintain effective nutrient pathways. The simple answer to limiting the chances of this scenario happening or at least extending it, is to stay alert and maintain a vigilant control of the incoming routes. Admittedly we can’t control all avenues, but we can have control over some.

This may sound a bit of an obvious statement, but even after the worst of disasters, there are always opportunities to improve on what we had before, correct errors in our methods, and try out new challenges. The real hurdle in any tank disaster is to keep that thought in mind.

As depressing as the situation may be, sharing a disaster with others both opens the door for much needed encouragement and makes you realise that you certainly aren’t the first person it has happened to, and you certainly won’t be the last.

As depressing as the situation may be, sharing a disaster with others both opens the door for much needed encouragement and makes you realise that you certainly aren’t the first person it has happened to, and you certainly won’t be the last.

0 Comments