Human or anthropogenic threats to coral reefs have been well documented for the past several years. Suddenly, there appears to be a surge in both research and legislative action regarding how human activities affect coral reefs. Here in Maryland, the health of the Chesapeake Bay has been a controversial topic and an issue that many politicians didn’t address in the past. Sensitive bay watersheds have been effected by both urban sprawl and large factory farms, who produce phosphorous rich run-off responsible for creating dead-zones within the once sea life rich bay. In the past four years ample political clout has been thrown into cleaning up the bay, with the formation of a Chesapeake Bay preservation trust, made up of scientists and ecology experts and funded via the tax payer. The results have been promising, as areas of the bay are showing signs of recovery and species that have been avoiding the waterway for years are starting to return.

Human or anthropogenic threats to coral reefs have been well documented for the past several years. Suddenly, there appears to be a surge in both research and legislative action regarding how human activities affect coral reefs. Here in Maryland, the health of the Chesapeake Bay has been a controversial topic and an issue that many politicians didn’t address in the past. Sensitive bay watersheds have been effected by both urban sprawl and large factory farms, who produce phosphorous rich run-off responsible for creating dead-zones within the once sea life rich bay. In the past four years ample political clout has been thrown into cleaning up the bay, with the formation of a Chesapeake Bay preservation trust, made up of scientists and ecology experts and funded via the tax payer. The results have been promising, as areas of the bay are showing signs of recovery and species that have been avoiding the waterway for years are starting to return.

Threats to coral reefs often lie outside the jurisdiction of state or federal agencies, as they exist in remote areas. Agencies are limited to controlling what imports arrive stateside, which have contributed to coral reef degeneration. To make matters worse, the residents of these island nations often have little economic opportunity, relying on their reefs as a source of income generation. Corporations from around the world have abused this reality, paying islanders insignificant wages to harvest animals for both the aquarium trade and the seafood industry. Even worse, corporations have harvested building materials from the reef, which often pushes acre upon acre of coral reef to complete devastation.

As sustainability progresses dialogue among advanced marine aquarists, it’s important for hobbyists to know where the reef aquarium trade (and eventually hobby) ranks among the myriad of anthropogenic stressors to coral reef health. The marine livestock industry often reminds hobbyists that the pressure they place on coral reefs is meniscal when compared to other industries. I think many marine aquarists would be surprised to learn that the collection of marine livestock ranks as one of the top human caused stressors to coral reef ecosystems. Both regulatory agencies and conservation outlets have been monitoring the collection of marine livestock for some time and report a series of abuses from various links in the supply chain. To help aquarists become aware of what anthropogenic activities are threatening coral reefs, I’ve compiled a list starting with the most severe on down, placing the collection of livestock on the list, in the area where most agencies believe it belongs. Since our main concern as aquarists is reforming practices that may damage wild reefs, I have concentrated most of the information on practices related to aquarium collection.

As sustainability progresses dialogue among advanced marine aquarists, it’s important for hobbyists to know where the reef aquarium trade (and eventually hobby) ranks among the myriad of anthropogenic stressors to coral reef health. The marine livestock industry often reminds hobbyists that the pressure they place on coral reefs is meniscal when compared to other industries. I think many marine aquarists would be surprised to learn that the collection of marine livestock ranks as one of the top human caused stressors to coral reef ecosystems. Both regulatory agencies and conservation outlets have been monitoring the collection of marine livestock for some time and report a series of abuses from various links in the supply chain. To help aquarists become aware of what anthropogenic activities are threatening coral reefs, I’ve compiled a list starting with the most severe on down, placing the collection of livestock on the list, in the area where most agencies believe it belongs. Since our main concern as aquarists is reforming practices that may damage wild reefs, I have concentrated most of the information on practices related to aquarium collection.

- Pollution: Coastal development, de-forestation, dredging, sewage treatment plant operation and agriculture expansion all contribute to the pollution of coral reefs. These activities produce nutrient rich run-off, which spurs the growth of algae, including zooanthellae within coral tissues. This sudden overgrowth eventually causes corals to expel their symbiotic algae, bleach and die. This is considered the most severe stressor to coral reef health worldwide. Runoff can be laden with sediment, nutrients, chemicals, oil, insecticides and other harmful compounds. Reefs are also polluted by leaking watercraft fuels, anti-fouling paints, various ship coatings and other chemicals that make their way into the water.

Surprisingly oil spills don’t have the impact on coral reef health that many would believe. The oil mainly remains at the water’s surface, evaporating into the atmosphere within a matter of days or weeks. Oil spills do seriously impact coral reef spawning. Often coral eggs will rise to the surface before being fertilized and settling on the reef. During an oil spill, the spawn is trapped within the oil and killed before it can settle on the reef. So while oil spills don’t directly have a severe impact on corals already settled on the reef, they can damage the spread and growth of coral reefs by interfering with spawning.

Surprisingly oil spills don’t have the impact on coral reef health that many would believe. The oil mainly remains at the water’s surface, evaporating into the atmosphere within a matter of days or weeks. Oil spills do seriously impact coral reef spawning. Often coral eggs will rise to the surface before being fertilized and settling on the reef. During an oil spill, the spawn is trapped within the oil and killed before it can settle on the reef. So while oil spills don’t directly have a severe impact on corals already settled on the reef, they can damage the spread and growth of coral reefs by interfering with spawning.

- Aquarium livestock collection: The collection of both marine fish and corals has led to widespread destruction of reef habitat. Collectors are often untrained, trampling corals while searching for specific species or colorful fish. Blast fishing is a process where dynamite is placed on the reef and set off, breaking up large stands of habitat and releasing fish for collectors. Cyanide fishing is used to stun fish so that they are easily netted by collectors. The cyanide that stuns the fish indiscriminately kills corals and causes widespread devastation. Currently over 40 countries actively use blast fishing and 15 countries still implement cyanide fishing. Since accurate statistics from remote island nations are unavailable, we are often left looking at information we have, which surrounds livestock collection in the Hawaiian Islands.

In 2011, on the big island of Hawaii a dumpster was found filled with dead yellow tangs, which had been placed in garbage bags and thrown away. The Hawaiian division of aquatic resources laid out each of the yellow tangs, counting a total of 551. It’s believed that a collector either froze the tangs one by one as they died, or experienced a mass die-off when a holding system became contaminated. The event became the poster child of stricter collection guidelines, when the Hawaiian Humane Society noted that massive loss of captured marine life was of little concern to collectors, since there were virtually no limits on collection.

It is estimated that 99 percent of fish collected from the Philippines and Indonesia die within one year of collection, largely due to the use of cyanide. According to a paper released by Yale University, those two nations supply about 85% of marine fish and invertebrates. In Hawaii alone, it is noted that 15,000 marine fish perish before being shipped out of the state. Many experts believe the actual death toll is two to five times higher than these officially reported statistics.

It is estimated that 99 percent of fish collected from the Philippines and Indonesia die within one year of collection, largely due to the use of cyanide. According to a paper released by Yale University, those two nations supply about 85% of marine fish and invertebrates. In Hawaii alone, it is noted that 15,000 marine fish perish before being shipped out of the state. Many experts believe the actual death toll is two to five times higher than these officially reported statistics.

Vetting:

Another area of marine fish collection that has hit the radar is vetting, often referred to as fizzing. The appropriate way to bring fish up from depth would be slowly, the same way a human diver ascends after a dive. Instead of taking time to ensure that fish don’t suffer some form of decompression illness, some collectors bring them to the surface quickly, allowing a massive pressure build up within the swim bladder. Once on the boat, the collector pierces the fish’s swim bladder with a hypodermic needle, relieving the pressure. Improper vetting can pierce other vital organs and when needles are re-used the procedure causes infection. Even in cases when vetting is properly administered, it does nothing to relieve potentially fatal pressure on the fish’s eyes, brain and other organs. It’s estimated that 9 percent of fish die after each leg of their journey into our aquariums. After collection 9 percent die, after exportation 9 percent die, after shipping to a vendor 9 percent die and when shipped to individual aquarists 9 percent die.

Another area of marine fish collection that has hit the radar is vetting, often referred to as fizzing. The appropriate way to bring fish up from depth would be slowly, the same way a human diver ascends after a dive. Instead of taking time to ensure that fish don’t suffer some form of decompression illness, some collectors bring them to the surface quickly, allowing a massive pressure build up within the swim bladder. Once on the boat, the collector pierces the fish’s swim bladder with a hypodermic needle, relieving the pressure. Improper vetting can pierce other vital organs and when needles are re-used the procedure causes infection. Even in cases when vetting is properly administered, it does nothing to relieve potentially fatal pressure on the fish’s eyes, brain and other organs. It’s estimated that 9 percent of fish die after each leg of their journey into our aquariums. After collection 9 percent die, after exportation 9 percent die, after shipping to a vendor 9 percent die and when shipped to individual aquarists 9 percent die.

What is post traumatic shipping disorder?

Stephanie Cottee, a researcher at the University of Guelph in Canada has theorized that many of the deaths blamed on unskilled aquarists actually have another cause. She theorizes that fish whom survive collection and arrive in an aquarist’s tank, have likely suffered such a great deal of trauma that they may shut down, leading to listless behavior and eventually perishing. It’s been noted that the disorder seems to effect some species more often than others, possible lending a hypothesis as to why certain species are considered “impossible to keep” in home aquariums.

Collection numbers:

According to reports, roughly 1.5-3.75 million marine fish and invertebrates are collected from Hawaiian waters. It’s estimated that the global total of marine animals collected for the aquarium trade exceeds 30 million.

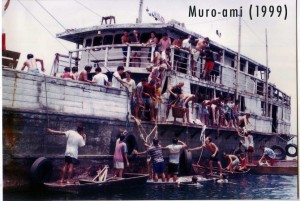

Other fishing practices: Deep water trawling and muro-ami netting damage coral reefs. Often deep water nets are left in areas of significant wave action, such as shallow coral reefs. Corals become entangled in these nets, which cause significant tissue damage or tear corals from their base. During muro-ami netting, large areas of reef are destroyed as weight bags are pounded down to break up habitat and release fish.

Other fishing practices: Deep water trawling and muro-ami netting damage coral reefs. Often deep water nets are left in areas of significant wave action, such as shallow coral reefs. Corals become entangled in these nets, which cause significant tissue damage or tear corals from their base. During muro-ami netting, large areas of reef are destroyed as weight bags are pounded down to break up habitat and release fish.

What’s taking place:

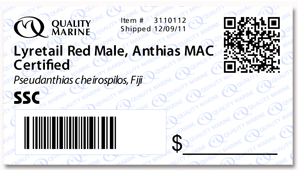

Quality Marine’s (a large marine livestock wholesaler) president Chris Buerner was quoted in 2013 saying, ““From an environmental perspective there could be specific species or specific areas that are pressured, but from a global perspective it’s nil. Nonetheless it’s a good thing if all the scrutiny pushes the industry toward lower-impact practices, adding, “There are things the trade really should work hard to improve.” Several marine wholesalers are taking steps to trace animal’s origins, helping guarantee that they haven’t been collected by those using destructive measures. In 2013 a new industry friendly labeling system was being developed called SMART, which will help make sure catch quotas are adhered too.

Quality Marine’s (a large marine livestock wholesaler) president Chris Buerner was quoted in 2013 saying, ““From an environmental perspective there could be specific species or specific areas that are pressured, but from a global perspective it’s nil. Nonetheless it’s a good thing if all the scrutiny pushes the industry toward lower-impact practices, adding, “There are things the trade really should work hard to improve.” Several marine wholesalers are taking steps to trace animal’s origins, helping guarantee that they haven’t been collected by those using destructive measures. In 2013 a new industry friendly labeling system was being developed called SMART, which will help make sure catch quotas are adhered too.

A recent breakthrough in sustainability is a test that can determine if a fish was collected using cyanide. The test could determine if imported fish were exposed to cyanide, allowing the industry to reject these animals with likely U.S. legislation making their purchase or sale illegal.

A recent breakthrough in sustainability is a test that can determine if a fish was collected using cyanide. The test could determine if imported fish were exposed to cyanide, allowing the industry to reject these animals with likely U.S. legislation making their purchase or sale illegal.

Aquaculture could help take the place of the 95 percent of marine fish imported from the wild. A new initiative by Sea World, called Rising Tide Conservation hopes to write the book on how to breed a variety of previously difficult species to cultivate in captivity.

According to experts who have spent time in Bali, an industry that was once dependent solely off wild collection is making strides towards becoming entirely aquaculture based. Conservation concerns focus on the fact that once you take away sustainable collection practices from indigenous fishermen, they may turn around to supply another industry with a less than perfect environmental track record.

As Bob Dylan once sang, “The times are a changing” and I would assume as coral reef health continues to move to the forefront of public policy, aquarists will be required to adapt and change as well, lessening our footprint on natural ecosystems.

As Bob Dylan once sang, “The times are a changing” and I would assume as coral reef health continues to move to the forefront of public policy, aquarists will be required to adapt and change as well, lessening our footprint on natural ecosystems.

0 Comments