The strange fish seen in this photograph was recently spotted by California Academy of Sciences ichthyologist Dr. Luiz Rocha on an expedition to the remote Trindade Island, part of a tiny archipelago that sits roughly 700 miles east of Brazil. While it may not immediately impress with any flashy colors, this was for much of the 20th century one of the rarest and least understood of Atlantic fishes, known from just three documented specimens.

The first was discovered in 1860 by local fisherman near Havana and brought to the attention of Cuban zoologist Felipe Poey. It bore a unique suite of morphological traits unlike any other Caribbean species and, while these fisherman presumed it to be a hybrid, Poey used this single specimen to describe a new species, Serranus dubius. In large part, this was based on the combination of a grouper-like head and an anthias-like lunate caudal fin, along with fin and scale counts which didn’t correspond to any known species.

In a study published in 1871 on Cuban serranids, Poey established a new genus for this species: Menephorus, a name that derives from the Greek for “lunate”, again in reference to the caudal fin. In 1875, a second species would surface from Cuba, Menephorus punctiferus, which differed in having numerous dark spots along its body. And this is more or less how things stood for the better part of a century. It wasn’t until 1966 that the hypothesis of the Cuban fisherman was at long last vindicated… the mysterious Menephorus really is nothing more than a hybrid of the Coney (Cephalopholis fulva) and the Creolefish (Paranthias furcifer).

We now have additional records from Bermuda and here at Trindade Island, illustrating that these two breed across their Western Atlantic distribution. Now, it might seem extraordinary that two distinct genera would be capable of interbreeding, but it wouldn’t be the first time this has been reported among reef fishes. Records exist of the Maroon Clownfishes (Premnas) hybridizing with several other anemonefishes (Amphiprion), and Bird Wrasses (Gomphosus) are known to successfully mate with Thalassoma wrasses.

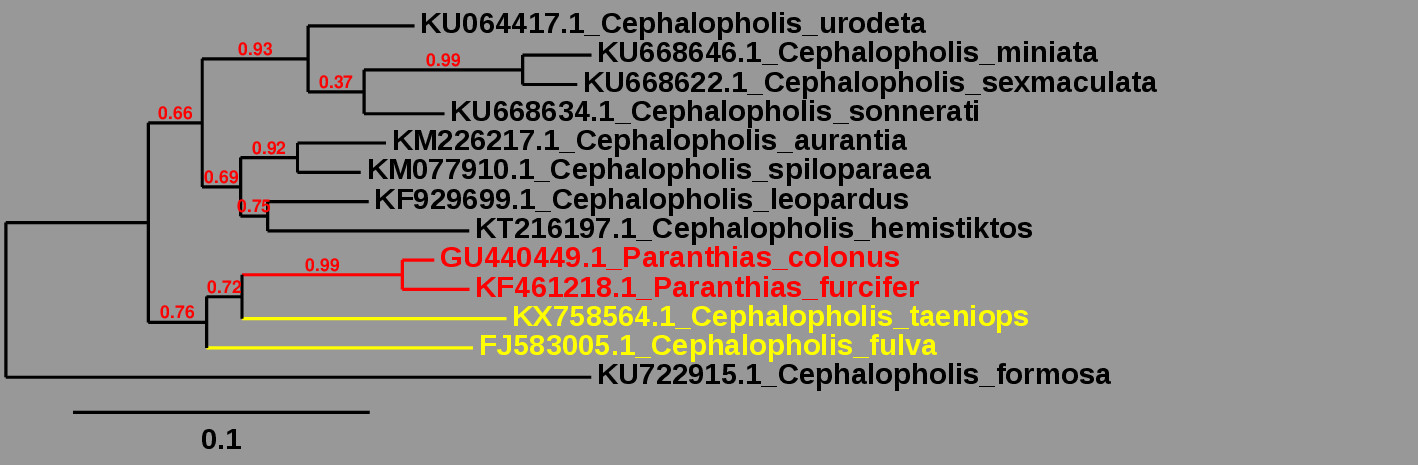

But this is fairly misleading, as all of these examples are really just a result of antiquated classifications. Gomphosus is now known to have evolved from within Thalassoma (i.e. they’re just a Thalassoma with a long face) and Premnas is the sister group to the Ocellaris and Percula Clownfishes. In that same vein, recent studies have convincingly shown that the shoaling, planktivorous Creolefish is actually derived from among the benthic predators of the Cephalopholis lineage (and the same is true for the former genera Aethaloperca and Gracila). In fact, “Paranthias” appears to be a close relative of both the Coney and another nearly identical species, the African Hind (C. taeniops). It’s still common to see “Paranthias” treated as a distinct taxon, but many newer publications have recognized the writing on the walls and have rightfully abandoned the name as a synonym.

In many ways, the “Menophorus” hybrid is a perfect blend of these parent species. In C. fulva, the head is angular and the caudal fin truncate, while in C. furcifer the head is rounded and the tail lunate. In the hybrid these traits are both intermediately developed. Additionally, the fin ray, gill raker and scale counts are ambiguous, and the presence of spots can be highly variable—the holotype had none, the photographed specimen seen here has many.

But given the considerable ecological and behavioral differences that separate these two, it’s somewhat surprising that they manage to interbreed in the first place. Genetic study has shown that all F1 and F2 specimens which have been studied thus far are the result of a female C. fulva breeding with a male C. furcifer. Yet to be determined is whether this is an intentional act on the part of these male Creolefish or perhaps just an accidental occurrence of a female Coney releasing her eggs near the sperm-clouded waters of a spawning Creolefish aggregation. Also unknown is whether some genetic or behavioral barrier serves to keep the opposite pairing from forming: a male C. fulva with a female C. furcifer.

Left: Creolefish (Cephalopholis (=Paranthias) furcifer) Right: Coney: Cephalopholis fulva. Credit: Robert Patzner / fishbase

- Bostrom, M.A., Collette, B.B., Luckhurst, B.E., Reece, K.S. and Graves, J.E., 2002. Hybridization between two serranids, the coney (Cephalopholis fulva) and the creole-fish (Paranthias furcifer), at Bermuda. Fishery Bulletin, 100(4), pp.651-661.

- Craig, M.T. and Hastings, P.A., 2007. A molecular phylogeny of the groupers of the subfamily Epinephelinae (Serranidae) with a revised classification of the Epinephelini. Ichthyological Research, 54(1), pp.1-17.

- Poey, F., 1858. Memorias sobra la historia natural de la Isla de Cuba, acompanadas de sumarios Latinos y extractos en Frances. Mem Hist Nat Cuba, 2, pp.1-442.

- Poey, F., 1874. III.—Genres des Poissons de la Faune de Cuba, appartenant à la Famille Percidæ, avec une Note d’introduction par J. Carson Brevoort. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 10(1), pp.27-79.

- Poey, F., 1875. Enumeratio piscium cubensium. (Parte Primera). Anales de la Sociedad Española de Historia Natural, Madrid v. 4 Imprenta de T. Fortanet.

- Smith, C.L., 1966. Menephorus Poey, a serranid genus based on two hybrids of Cephalopholis fulva and Paranthias furcifer, with comments on the systematic placement of Paranthias. American Museum novitates; no. 2276.

0 Comments