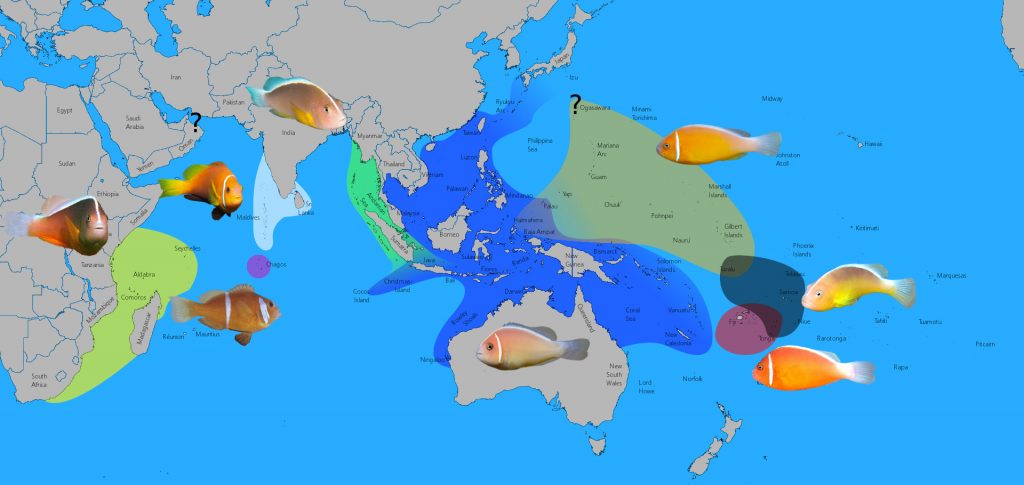

A recently published study is helping to shed some light upon a fascinating and poorly understood evolutionary puzzle concerning a group of familiar reef fishes. Within the hugely diverse genus Amphiprion, there is a distinctive lineage formed from species that have a white stripe along the back, extra scales above the head and a preference for the Magnificent Sea Anemone. These are the so-called Skunk Anemonefishes, which are represented by three species in the Pacific and one in the Indian Ocean. But the story gets far more complex…

In the Indian Ocean, the resident species is Amphiprion akallopisos, which is easily identified by its dorsal stripe and the lack of any vertical stripes. It occupies a pair of widely disjunct ranges, with one population along the East African coast and the other in the Eastern Indian Ocean and Java Sea. The distance separating the two (~4,500 km) is vast, but, despite this, there is little morphological evidence to suggest that these might be different species. This is definitely at odds with what we see elsewhere in the genus, as most other anemonefishes tend towards having small geographic ranges, resulting from their limited ability to disperse during their short larval development.

When we do encounter widespread anemonefish taxa, it’s usually a strong indicator that our current classification is hiding overlooked biodiversity. With these two populations of A. akallopisos, there is strong reason to suspect that they are actually evolutionarily distinct and deserving of separate species recognition. For instance, an earlier study (Parmentier et al 2005) found that the sounds produced by the fishes in these two regions differ considerably, meaning that they, in essence, speak different languages. And we now finally have some genetic data to back this up thanks to the recently published study of Huyghe & Kochzius 2016. Using hundreds of specimens from a wide number of locations, these authors found that the mitochondrial gene which they examined strongly differed between the populations, though the distinction was still rather subtle. These authors go on to argue that the eastern A. akallopisos populations may have directly given rise to the African population, as the former is more genetically diverse, suggesting a longer existence during which mutations could accrue. This makes some intuitive sense, but there is one major flaw to this explanation—there are no Skunk Anemonefishes in the Central Indian Ocean… at least, not in the traditional sense. So how could this fish have traversed the Indian Ocean to accomplish this feat?

This, dear reader, is where things get particularly interesting. When we venture into the Maldives, Sri Lanka and south into the Chagos Archipelago, instead of finding a skunk anemonefish in the mold of A. akallopisos, we find two very different looking fishes: A. nigripes and A. chagosensis. Neither has a dorsal stripe and neither looks all that much like the A. akallopisos populations which flanks them to the east and west. Still, we can surmise that these two are still legitimate, card-carrying skunk anemonefishes, as both possess the extra predorsal scales that help define the group and both exclusively use the Magnificent Sea Anemone (Heteractis magnifica) as their host anemone, an important ecological specialization found among all of the skunk anemonefishes (with the exception of the evolutionarily distinct A. sandaracinos).

So, how do we explain this curious situation? How do we get two nearly identical fishes in Africa and the Eastern Indian Ocean when the region between them seems to be an impassible barrier where this fish is entirely absent? If the eastern A. akallopisos truly gave rise to the western population, as Huyghe & Kochzius 2016 suggests, the only plausible route would have been across reefs of the Central Indian Ocean, where their ecological niche is already well-filled by A. nigripes and A. chagosensis. This, of course, provides our answer.

If we apply Occam’s Razor to this quandary, the most likely explanation is that the eastern A. akallopisos never actually populated the African region. Instead, if we were to travel back a suitable length of time, we would eventually arrive upon a moment when the entirety of the Indian Ocean has a single, homogeneous skunk anemonefish species that no doubt would have strongly resembled the A. akallopisos we know and love today. During the Pleistocene, massive sea level changes caused by glaciation would have disconnected the three major ecoregions of the Indian Ocean (Western, Central, Eastern), isolating these fishes and allowing them to diverge. Those in the east and west appear to have changed little in morphology, though subtle genetic and behavioral differences eventually built up.

On the other hand, the ancestral skunk anemonefish of the Central Indian Ocean took a very different path. The unique appearance of A. nigripes and A. chagosensis tells us that something unique happened here, something which probably can’t be explained by the normal processes of allopatric speciation. It’s when we look at the genetics of these two that we find our answer. Rather than appearing as close relatives of A. akallopisos or the Pacific Ocean A. perideraion, they instead show up as closest to a lineage of Western Indian Ocean (WIO) species that have most often been lumped alongside A. clarkii. This group—allardi, latifasciatus, bicinctus, etc—are morphologically distinct from the skunk anemonefishes and, rather than specializing in H. magnifica, these are anemone generalists, using just about any species that’s available. The two groups could hardly be any more different from one another, so why is the genetic data giving us such an unlikely result?

The answer I’ll propose is hybrid speciation. The differences seen in A. nigripes (and the very similar A. chagosensis) are the result of interbreeding between the ancestral skunk anemonefish of the Central Indian Ocean and a member of the WIO lineage which occasionally strayed into the region. The most likely suspect is A. omanensis, which, like A. nigripes, has dark ventral fins and is geographically closest to the reefs of Southern India. Today, this fish is almost entirely restricted to the Southern Arabian Peninsula, but, during the Pleistocene, it is not unreasonable to presume it was more widespread and could have crossed further to the east. Even today, Arabian fishes with longer pelagic larval development (e.g. Purple Tangs) do on rare occasion waif as far as the Maldives, illustrating how the currents might transport a fish into these distant waters.

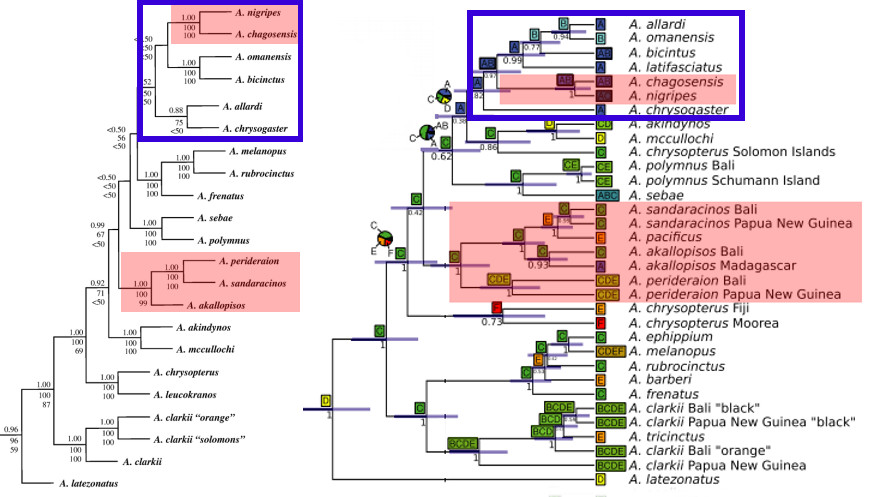

Mitochondrial (left) and nuclear (right) phylogenies. Red indicates the skunk anemonefish group, blue indicates the Western Indian Ocean group. Modified from Santini & Polacco 2006 and Litsios et al 2014

Both mitochondrial (Santini & Polacco 2006) and nuclear (Litsios et al 2014) data have shown the same sister relationship between the WIO lineage and A. nigripes+A. chagosensis. But, given their considerable morphological and behavioral differences, the most plausible explanation for this anomalous result may be genetic introgression resulting from interbreeding. Hybridization has already been shown to be a widespread phenomenon among Amphiprion, best exemplified by A. thiellei and A. leucokranos, both of which are hybrids formed from distantly related species groups.

Hybridization is common among Amphiprion, such as with these White-bonnet Anemonefishes, the result of A. chrysopterus X A. sandaracinos. Credit: Thane Militz

This is a satisfying answer, but one which requires far more study to confirm it. One could make the counterargument that A. akallopisos and the WIO lineage coexist just fine along the African coastline without any signs of hybridization. But this overlooks the tendency for hybridization to occur predominantly in areas where population levels for one or both parent species are low. Since neither of these fishes are rare in the west, it makes sense that hybridization would be minimal, whereas the limited ability of A. omanensis to venture eastward towards India would have likely forced any specimens that successfully completed the voyage into a flagrante delicto with the resident skunk anemonefish.

So many questions remain. If this hypothesis is correct, why did the WIO lineage interbreed with the skunk anemonefishes and not one of the other groups found around India? I understand that the heart wants what it wants, but it seems curious that a fish like A. omanensis wouldn’t pursue a relationship first with A. clarkii, which has a similar morphology and equally catholic tastes in host anemone. Alternatively, is it possible that the major phenotypic differences of A. nigripes and A. chagosensis occurred solely from allopatric isolation? If so, why did A. akallopisos remain so homogeneous in appearance and how do we explain the genetic discrepancies that argue against this? As with any good scientific mystery, investigation leaves us with as many questions as answers. Hopefully, some intrepid researcher will eventually pull back the curtain on these confounding little fishes.

- Huyghe, F., & Kochzius, M. (2016). Highly restricted gene flow between disjunct populations of the skunk clownfish (Amphiprion akallopisos) in the Indian Ocean. Marine Ecology.

- Litsios, G., Pearman, P. B., Lanterbecq, D., Tolou, N., & Salamin, N. (2014). The radiation of the clownfishes has two geographical replicates. Journal of Biogeography, 41(11), 2140-2149.

- Parmentier, E., Lagardère, J. P., Vandewalle, P., & Fine, M. L. (2005). Geographical variation in sound production in the anemonefish Amphiprion akallopisos. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 272(1573), 1697-1703.

- Santini, S., & Polacco, G. (2006). Finding Nemo: molecular phylogeny and evolution of the unusual life style of anemonefish. Gene, 385, 19-27.

0 Comments