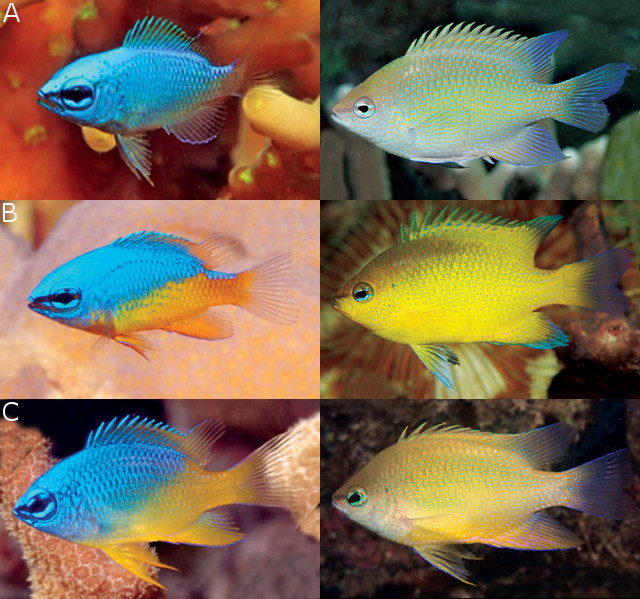

A: C. ellenae, from Raja Ampats B: C. maurineae, from Cenderawasih Bay C: C. oxycephala, from Bali & Palawan Credit: Allen et al 2015

Earlier this year I wrote a review for a popular group of damselfishes—the Chrsyiptera hemicyanea complex—that show a complicated pattern of regional speciation. At the time, several of these biogeographical variants remained scientifically undescribed, but a new study by Gerry Allen and coauthors has addressed this gap in our knowledge, describing three new species in an important paper on the region’s population genetics. When combined with previous work in this field, a clearer picture is now developing of the processes that dictate the immense diversity surrounding the island of New Guinea.

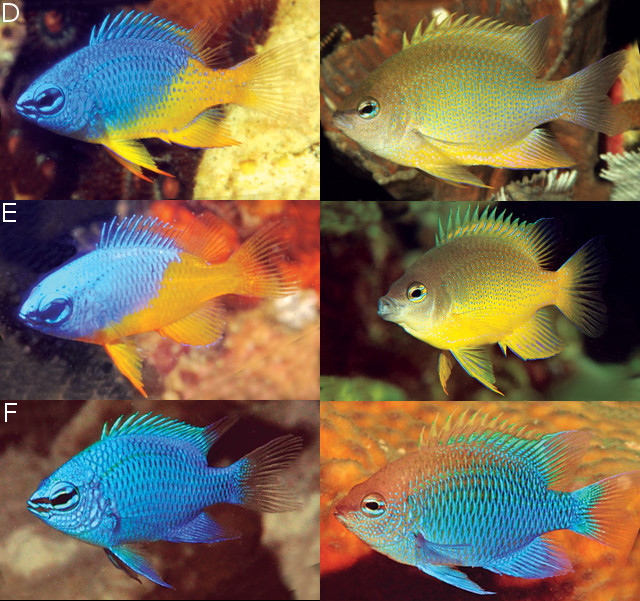

D: C. cf oxycephala “genovariant” from Lembeh E: C. papuensis, from Milne Bay F: C. sinclairi, from Manus Island & Hermit Islands Credit: Allen et al 2015

For aquarists, Chrysiptera oxycephala is a relatively unfamiliar and unpopular species, with adults suffering from a relatively drab mix of dingy yellow and brown. Juveniles, on the other hand, are vibrant blue and yellow fishes which show their allegiance more clearly to the other colorful members of their species group—familiar offerings like the Yellowtail, Azure and Springer’s Damselfishes. However, juveniles from different locations of the Coral Triangle were noted to differ in the configuration of their patterning, often moreso than in the adults, which ultimately led these researchers to search for overlooked species diversity.

Previous biogeographical studies of the Coral Triangle have strongly hinted at a major region of endemism centered on the island of New Guinea, which also includes the Solomon Islands in the east and the Muluku Islands to the West. The present study of C. oxycephala adds even more detail to this, as these newly recognized taxa are all exclusively endemic within this Melanesian ecoregion. While many other reef fishes from here—for instance, Chaetodontoplus poliourus or Amphiprion percula—can be found as seemingly homogenous populations spanning this entire region, these new damselfishes break down into multiple geographically restricted subpopulations now treated as distinct taxa.

The maps and photographs included here give a brief account of the findings from Allen et al, which is expounded upon in far more detail in their paper. Overall, morphological differences between these taxa are minimal. C. maurineae, described from Cenderawasih Bay, is said to have (on average) one extra lateral line scale, as does an undescribed variant of C. oxycephala from Lembeh, Sulawesi. This latter fish is particularly noteworthy, as it showed more genetic divergence (~3%) from other populations of its species than what was found between some of the newly described taxa. This could certainly have been used to justify describing this as yet another new species, but observable differences in color and morphology don’t exist here. The authors instead used the term “genovariant” to highlight the genetic uniqueness of this fish, without actually affording it a taxonomy of its own.

But consider the many other endemics from this region which do show clear phenotypic differences—Paracheilinus togeanensis, Cirrhilabrus aurantidorsalis, Pictichromis dinar—and it becomes clear that there is more to this story than meets the eye. This raises a challenging question for taxonomists: how do we classify phenotypically identical fishes when the genetics differ? In essence, just because a fish looks the same, is it truly the same from an evolutionary perspective? Unfortunately, only a single genetic marker was studied in C. oxycephala, which limits the ability for such difficult questions to be answered. But such seemingly esoteric questions are important to answer when it comes to properly conserving the diversity of these coral reefs.

This study also highlights the likely presence of another undescribed species in the Solomon Islands, which shows significant differences in both adult and juvenile coloration. Specimens were unavailable for study, and thus it remains as a known unknown. Additional areas of inquiry still remain, principally as it relates to possible differences between the populations of C. oxycephala spread from the Philippines to the Java Sea and Palau. In many other groups of fishes (e.g. Paracheilinus, Amphiprion, Pseudochromis, even other Chrysiptera) these regions harbor distinct species split into northern and southern populations, roughly divided along a boundary located near northern Sulawesi and Mindanao. There are hints of this in the “genovariant” from Lembeh, but the single gene studied here paints an unclear picture. More exhaustive genetic research would likely yield a clearer delineation.

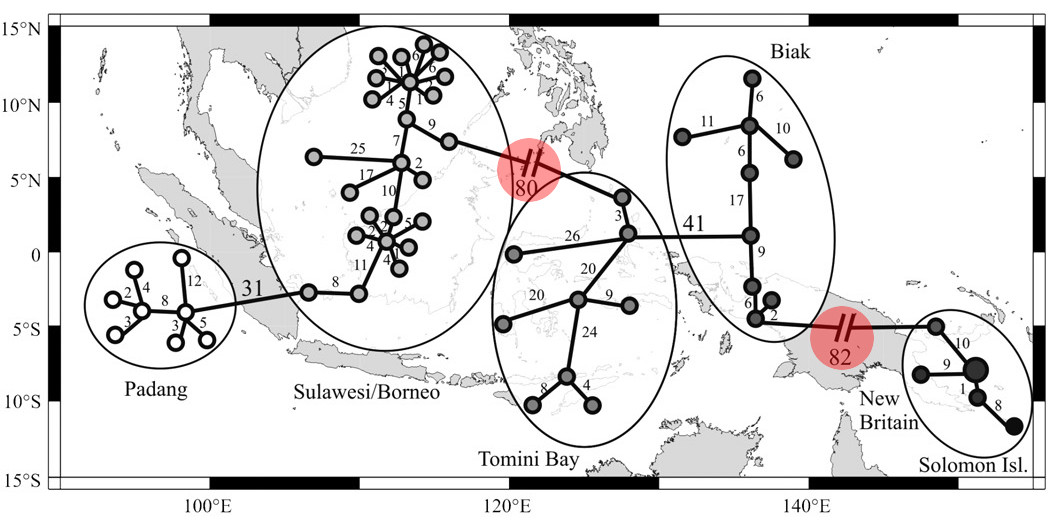

A map showing the population genetics of Percula and Occelaris Clownfishes. The red circles indicate the major genetic breaks in the group, hinting at an undescribed species from Eastern New Guinea, and perhaps two others, in the Indian Ocean and Western New Guinea. Credit: Timm et al 2008

It’s not always easy for aquarists to get excited for a fish like C. oxycephala and its handful of nearly identical siblings. They’re not the most beautiful of fishes to look at, and their somewhat undeserved reputation for bellicosity renders them unwanted by most. But there are important insights to be gained by understanding and appreciating the diversity of this group, as it can greatly help to inform how we classify other widespread species in this region.

For instance, a previous study of Percula and Ocellaris Clownfishes has shown a similar genetic distribution, hinting at cryptic species in these aquarium stalwarts. The Bicolor Dottyback is another likely example of a group with hidden Melanesian species-level diversity. I’ll be delving into this thorny issue with upcoming reviews of both groups later next year. What should be becoming increasingly clear is that our understanding of the true scope of coral reef biodiversity is still in a very nascent state, and widespread taxa are often just an artifact of our own ignorance of a group’s hidden evolutionary history.

Sarah Neill Lara Mingay x

Sarah Neill Lara Mingay x

Sarah Neill Lara Mingay x

Me gustan los peces

Me gustan los peces

Me gustan los peces