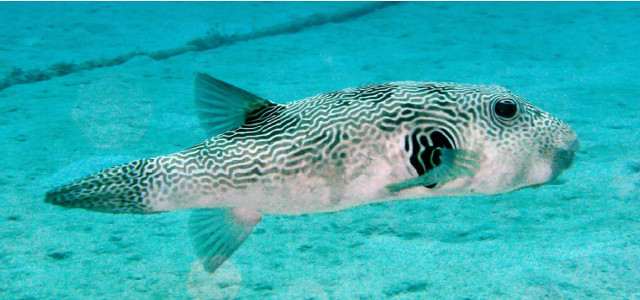

It’s not every day that a new species of large pufferfish is described from Indo-Pacific coral reefs, but such is the case with the recent description of Arothron multilineatus, a girthy fish documented from Japan and the Red Sea. Reported to reach a length of nearly 18 inches and adorned in an attractive pattern of wavy lines, this is one of the more surprising discoveries in recent memory, but one not without some controversy.

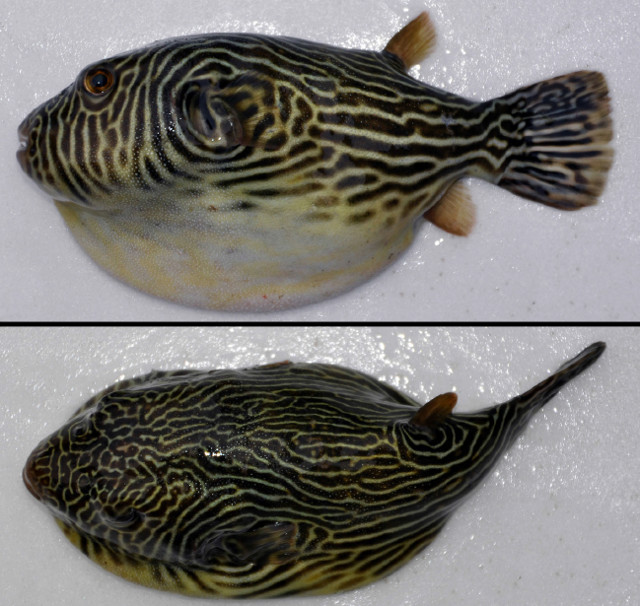

There are some important concerns which must be raised about the legitimacy of this newly recognized species, as the paper describing it relied exclusively on differences in its color pattern to diagnose it from others in the genus. This is particularly questionable given the limited number of specimens studied (4 from Japan and 2 photographs from the Red Sea) and the considerable differences in patterning seen across these specimens. Genetic data would have gone a long way towards supporting the author’s claims, but, unfortunately, none was included.

The obvious question to ask here is how this sizable pufferfish has been able to elude the attention of divers, aquarists and zoologists up until now, especially considering it occurs in shallow reef habitats in some of the most well-dived locations on the planet. I’ve examined this genus in considerable detail for an upcoming article, using the extensive diver photography which exists in online image repositories, and I’ve found that specimens conforming to the description of A. multilineatus are tremendously rare. Out of hundreds of pufferfishes observed in the Indo-west Pacific, only a handful of examples can be confirmed. This is an entirely implausible population level to support a reproductively viable species, but it does support an entirely different hypothesis for what this phenotype represents.

- Ryukyu Islands, Japan. Credit: Kimiaki Ito

- Red Sea. Credit: Richard Field

- Red Sea. Credit: Richard Field

- Phuket, Thailand. Credit: unknown

- Ishigaki, Japan. Credit: Purity Diving

- Philippines. Credit: O. Neussner

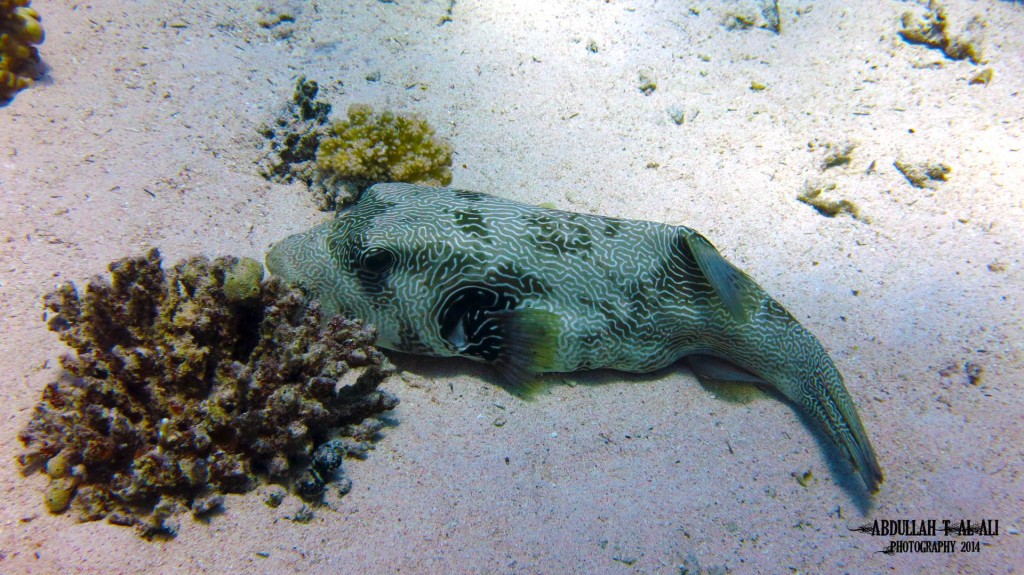

- Red Sea. Credit: Abdullah T. al Ali

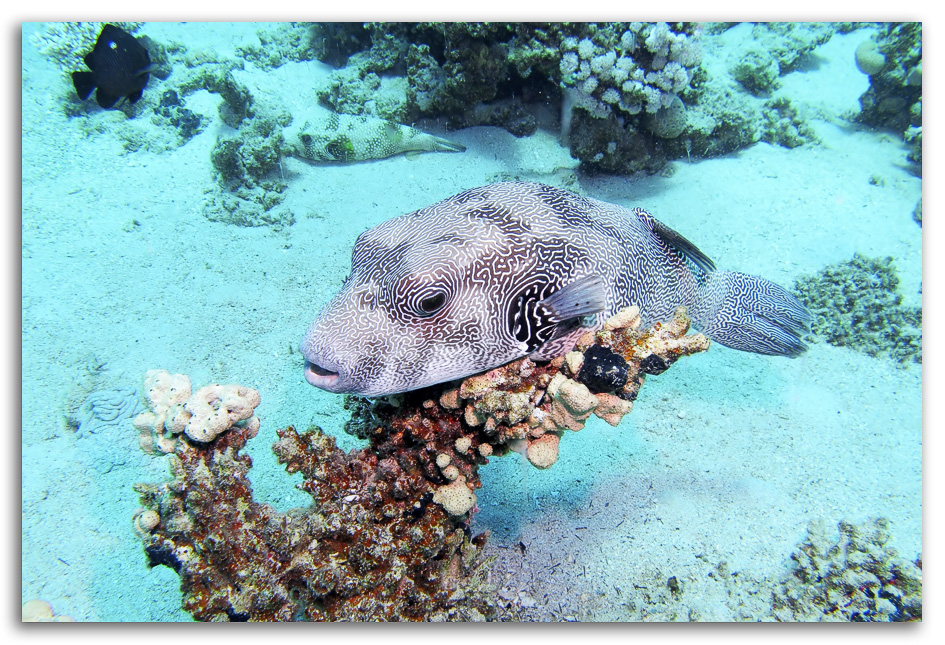

- Red Sea. Credit: unknown

- Red Sea. Credit: Paul Britton

- Red Sea. Credit: Paul Britton

- Red Sea. Credit: Paul Britton

- Red Sea. Credit: David Whistlecraft

Rare phenotypes are often a strong indication for a hybrid origin, and, for A. multilineatus, the presence of specimens in the Red Sea severely limits the possible parent species. Ruling out the entirely different-looking A. dimidiatus, we are left with two species native to these waters: the Starry Pufferfish A. stellatus and the regional variation of the White-spotted Pufferfish A. hispidus.

The Red Sea variation of A. hispidus is distinct in its patterning. Note the white spots on a grey background. Credit: John Randall

It’s important to note that both of these species grow to a similar size as that reported for A. multilineatus, and all three share a similar shape to the body. The Red Sea population of A. hispidus is actually quite distinct from those found elsewhere, as the body is heavily spotted, generally devoid of stripes along the sides and belly, grey in color and with numerous rings encircling the eyes—this has lead to it having been described as a distinct species, A. perspicillatus, though currently this name is (perhaps incorrectly) treated as a synonym. These ringed eyes show up again in many of the A. multilineatus specimens illustrated here, but it is noteworthy that some specimens instead show an irregular maze-like pattern. Such variation is often the hallmark of hybridization.

Arothron stellatus has dark spots on a light body. How might this pattern interplay if crossbred with A. hispidus? Credit: John Randall

Much about the patterning along the body and fins varies as well, though the same can be said for most of the members of this genus. Many Arothron can be quite variable in appearance based on factors such as geography, age and perhaps from sexual differences as well, though minimal research has been done to document any of this in proper detail. Still, the variations seen in A. multilineatus appear far greater than should be expected from a single species, varying from a highly linear pattern to byzantine convolutions. Note also the differences in the caudal fin patterning, which can appear either spotted, linear or more stochastically arranged. And, lastly, the presence of three indistinct dark bands beneath the head are a hallmark of A. hispidus and A. stellatus and are otherwise not seen in related species, but they can be observed in the A. multilineatus phenotype.

- A. reticularis. Strongly reticulated specimen. Credit: unknown

- A. reticularis, aquarium. Credit: Kaikyokan

- A. reticularis, Australia. Credit: John Randall

- A. reticularis, aquarium. Credit: unknown

- A. reticularis, aquarium. Credit: unknown

- A. reticularis, aquarium. Credit: unknown

- A. reticularis, aquarium. Credit: msfishlover

- A. reticularis, aquarium. Credit: unknown

- A. reticularis, aquarium. Credit: Yadokoriya

- A. reticularis, aquarium. Credit: unknown

- A. reticularis, Okinawa. Very hispidus-like. Credit: Ocean-blue

- A. reticularis, Okinawa. Very hispidus-like Credit: Toru Seko

- A. reticularis, aquarium. Credit: Yadokoriya

- A. reticularis, Yaeyama Islands. Very hispidus-like. Credit: Hiroshi Senou

We need to bring a couple more species into this discussion that bear some relevance. The first is A. reticularis, the apparent sister species of A. hispidus, which ranges from India through the West Pacific. It is said to differ ecologically in its preference for silty habitats, often near estuaries, and it can be recognized from the stripes (formed of the coalesced white spots found in A. hispidus) that fill the head and run along the belly. Given the variation seen in A. multilineatus specimens, it would not be surprising if some of the more thickly-striped and linear examples represent hybrids with this species, rather than with A. hispidus.

- One of three confirmed specimens of A. carduus. Credit: Keiichi Matsuura

- A lampshade curio of A. carduus. Credit: Keiichi Matsuura

The poorly known A. carduus shows a similar appearance, and had in fact been treated as a synonym up until a recent reappraisal by Keiichi Matsuura (who also described A. multilineatus). The damaged holotype specimen—a one-hundred year old piece of dried skin representing half the animal—is of little diagnostic value, especially considering how variable we know these fishes can appear. Only two other specimens are apparently known, both from Japan. This fish is heavily striped in black and white along the back and sides, with an unmarked white belly. Interestingly, there are numerous small black spots in places, which would seem to indicate that this fish has its color palette reversed with respect to A. hispidus (which has white spots in the same locations), though note that some examples of A. multilineatus seem to share these same dark spots along the head and sides. It’s hard to know what to make of the A. carduus phenotype, but, given its exceedingly rare nature, this could very well represent yet another hybrid form.

And then there’s this bizarre specimen. Is this a variant of A. reticularis? Or A. carduus? Or A. multilineatus? From Izu Islands, Japan. Credit: Yukiko Yokokawa

With so few specimens of A. multilineatus and no genetic data to go off of, let’s try applying Occam’s Razor to this. Which scenario is more likely: 1) There is a large, ornately-patterned pufferfish spread across the whole of the Indo-Pacific in shallow waters that has somehow evaded all previous researchers and fish collectors and which remains known only from a handful of specimens, while others in the genus are abundant and well-documented. Or… 2) There is a rare and previously overlooked hybrid. Ultimately, this issue is likely to remain unresolved until a proper taxonomic revision is done, one which includes thorough genetic study.

0 Comments