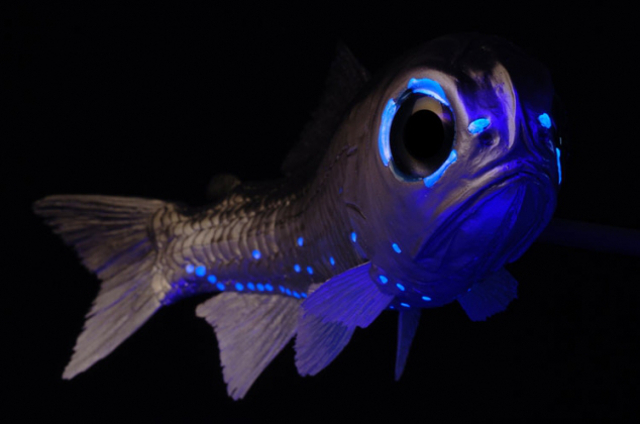

A model of the Headlightfish Diaphus rafinesquii, a type of Lanternfish. Credit: Museo de Ciencias Naturales Senckenberg

Deepwater fishes hold an undeniable fascination in the hearts and minds of many an aquarist, but, alas, these bizarre denizens of the deep are impossible to acquire for the home hobbyist. However, what is often not appreciated is that there are several groups of mesopelagic fish which regularly ascend into the shallow waters around coral reefs and could, in theory, be targeted by aquarium collectors. The most abundant of these are the remarkable little bioluminescent fishes from the Family Myctophidae known commonly as Lanternfishes.

Benthosema sp. seen in Bali at 5 meters. Credit: manboon

Myctophids are a perfect example of an animal which should be more widely known among the general public. These small, unassuming creatures are prolific on a monumental scale and are widely assumed to be amongst the most numerous of marine fishes, forming upwards of 65% of the biomass in their mesopelagic realm. Shoals of lanternfishes can be so dense as to reflect back sonar (due to the hollows of their swimbladders); this was discovered during the second world war, when sonar operators noticed a false bottom to the ocean at several hundred meters that changed position during the course of the day—the so-called “Deep Scattering Layer”.

Lanternfishes undergo huge vertical migrations of hundred of meters as they follow their zooplanktivorous prey upwards at night. Their journey typically begins shortly before sunset, and, at its peak, myctophids (and many other deepwater fish families) can be plucked from the surface waters, offering the possibility for their capture in the aquarium trade. In fact, researchers have been doing so for years in order to better study the luminescent properties of this group.

Lanternfish photophores have a modified lenticular scale to diffuse the light produced beneath it. Credit: Joan Costa/CSIC

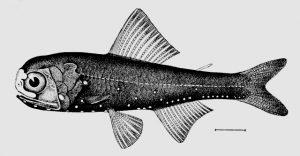

Illustration of the Headlightfish Diaphus metopoclampus showing the serial photophores along the belly and the large luminous organ near the eye common to this genus. Source: Goode & Bean, 1896

Myctophid luminescence is the result of a luciferin-luciferase reaction—the same chemistry which creates the cold light of fireflies. This is fundamentally different from the other group of shallow-water bioluminescent fishes: the Flashlightfishes of the Family Anomalopidae, which have a specialized organ for culturing light-producing bacteria. The soft, bluish glow emitted by lanternfishes occurs in small circular organs known as photophores lining the undersides of the body, providing the fish with “counter-illumination”. This serves to mask the fish’s outline from below when seen against the small amount of blue light that reaches the mesopelagic depths.

The Mexican Lampfish (Triphoturus mexicanus) is the most abundant fish in the mesopelagic waters of Baja. Specimens observed in situ often adopt a vertical swimming orientation, which seems to negate the “counter-illumination” provided by the photophores. Credit: MBARI

There are roughly 250 species of lanternfish, and each is said to possess its own unique arrangement to its photophores, making these structures highly important for species recognition amongst both fish and scientist alike. Many also have additional patches of luminous tissue that serve a more direct role in intraspecific communication. In some, such as the Headlightfish Diaphus, the luminous organs occur in association with the eyes, while in others these organs are positioned on the caudal peduncle and are sexually dimorphic, with males having them dorsally and females ventrally. Unlike the serially arranged photophores, which emit a constant blue light, these other types of luminous organs are behaviorally controlled and only briefly flashed when communicating. One unusual observation was made when a researcher unwittingly held the phosphorescent dial of his watch near a captive lanternfish, which the fish proceeded to respond to with its own flash of light.

Benthosema lanternfish seen along a reef in Palau. Credit: manboon

The most abundant species in shallow tropical waters are typically Benthosema pterotum and B. fibulatum, though Diaphus, Myctophum and Hygophum are also commonly trawled near surface waters. Specimens captured in this manner, particularly for Benthosema, are reported to lose many of their scales and would likely prove difficult to keep in captivity long-term. Should specimens ever be targeted for the aquarium trade, they would likely need to be hand-netted and transported quite carefully to avoid damage. One trait working to this fish’s advantage though is their ability to tolerate low oxygen levels, an adaptation to similar conditions often found in the mesopelagic depths.

The typical lifespan for a lanternfish is said to vary from 1-5 years, though it’s likely captive specimens could prove longer lived. In the wild, myctophids are on the menu for many different animals, from larger deepwater fishes to penguins and dolphins, undoubtedly making it challenging for them to grow to a ripe old age. Their delectability relates to their high fat content—so fatty are these fishes that consumption in large quantities is said to cause diarrhoea. For this reason, as well as the difficulties in processing these small fishes, they have limited utility for our own species, being mostly used as fertilizers and animal feed.

While lanternfishes may not be as aesthetically grotesque as some of the other specialized fishes with which it shares its deepwater home, they are nonetheless fascinating little fishes and one which could make for a truly unique aquarium display. Hopefully someday soon aquarium collectors can make these available, as I imagine I’m not the only one who’d like to keep a school of these glowing beasts.

0 Comments