The “japonicus” variant of the Powder Brown Surgeonfish, from Okinawa. Credit: yusuke

The challenges of recognizing what is and is not a “species” has proven to be one of the most vexing questions in all of science, and nowhere do these limitations to our understanding seem more evident than with our current classification of Indo-Pacific reef fishes. Commonly shared patterns in the biogeography of these fishes indicates that past glacial cycles have done much to shape the distribution and speciation of today’s fauna. We know that the Indian and Pacific Oceans have often been separated by the Sunda Shelf of Indonesia during periods of lowered sea level, as can be seen in the many so-called geminate species split by this barrier. But less is known about what happens when barriers like this are removed and the new “species” begin to once again interbreed.

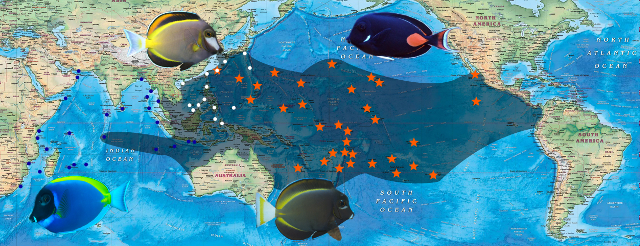

Biogeography of the A. nigricans complex. The widespread A. nigricans is shown in black. Note that the relative abundance of these species often varies widely across their ranges (e.g. A. nigricans is rare at Diego Garcia, A. achilles is a waif in Japan, “japonicus” is rare in Indonesia).

A newly published study has taken a closer look at this issue by examining in great genetic detail a familiar group of aquarium surgeonfishes with a noted propensity for hybridization—the Acanthurus nigricans complex. Included here are four recognized species which display a range of biogeographical patterns, from a pair of widespread geminate taxa to those with more endemic distributions.

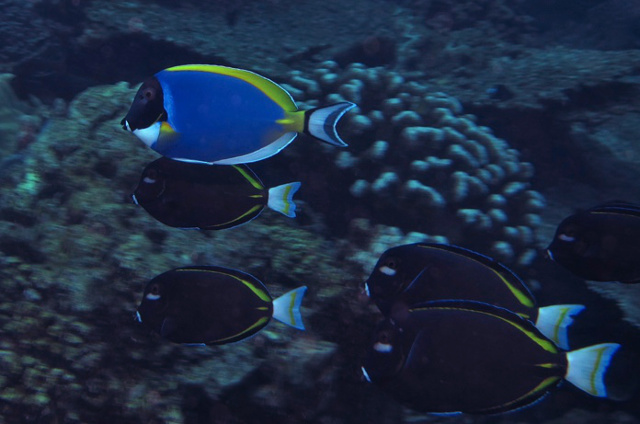

A mixed-species school seen at Christmas Island, formed of the Indian Ocean A. leucosternon and the Pacific Ocean A. nigricans. Credit: Eunice Khoo

The Powder Blue Surgeonfish (A. leucosternon) is an Indian Ocean endemic that occurs in large schools which spread across the reefs in their endless search for algae. In the Pacific, it finds itself replaced by a very similar fish, the Powder Brown Surgeonfish (A. nigricans), which has a vast range encompassing all the coral reefs of the Pacific, including those of the Eastern Pacific. In addition, there is the beautiful and expensive Achilles Surgeonfish (A. achilles) which is abundant throughout Polynesia, becoming increasingly rare in Micronesia and Japan. This territorial fish lives in shallow sections of the reef experiencing heavy surge, defending these patches in much the same way as we see in the distantly related Clown Surgeonfish (A. lineatus).

The last member of this group is a far more contentious fish, the Japanese Surgeonfish (A. japonicus), which occurs in varying abundance throughout Japan, the Philippines and a few northern portions of Indonesia. This range is precisely what we might expect for a species endemic to Japan (particularly one with a notably long-lived pelagic larva that could disperse further south than usual), but the fact that it coöccurs with the nearly indistinguishable A. nigricans throughout its range has long called into question the legitimacy of this species.

Mixed pairs of the japonicus and nigricans phenotypes, from Okinawa. Credit: okinawa365 & kiss2sea

Think of what might best explain this peculiar situation. We could argue that A. japonicus speciated at some point in the recent past when sea levels were lowered and Japan was, in theory, less connected to the reefs of the Coral Triangle. When sea levels rose again, these two discrete populations would then be able to expand into each other’s ranges, which these fishes would excel at given their long larval stage. An alternate hypothesis might be that some amount of sexual selection or ecological specialization fostered the splitting of these two phenotypes without the need for any geographic separation. Such “sympatric speciation” is indeed likely for groups which rely heavily on their sexual color patterns to distinguish themselves from related species (e.g. Paracheilinus flasherwrasses), but seems unlikely for this group of surgeonfishes. Ecological separation likewise seems implausible, as no real distinction has been documented for A. japonicus and A. nigricans, and, in fact, the two have frequently been seen to occur together in the wild.

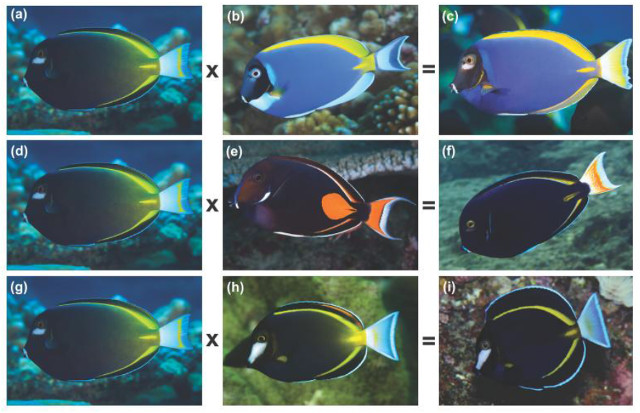

This nigricans X achilles hybrid was observed in Guam, near the western limits of where the Achilles Surgeonfish can be found. DiBattista et al 2016 examined seven similar specimens, finding each contained nigricans mitochondrial DNA, which suggests that this hybrid might always involves a male A. achilles and a female A. nigricans. Credit: Luiz Rocha

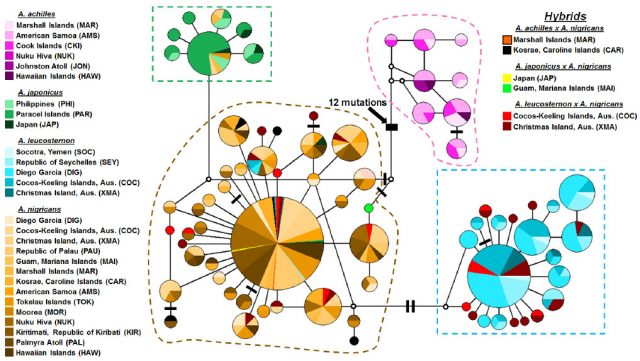

The genetic study of DiBattista et al 2016 is helping to at last add some clarity to this issue, as the mitochondrial data examined supports what has long been suspected—there is little difference between these two phenotypically distinct fishes. While specimens of A. japonicus do share similarities in their DNA (known as haplotypes), they share these precise similarities with certain individuals of A. nigricans. What’s more, four specimens which possessed a “japonicus” phenotype had nigricans DNA, while seven specimens with the “nigricans” phenotype had a japonicus haplotype, including specimens as far away as Kiritimati, Tokelau and Cocos-Keeling Island. This could suggest that the hybrids of these two have dispersed far and wide, or, conversely, it might argue that the two were never that different to begin with. While the authors resist the urge to make any formal taxonomic revision on the matter, it seems clear that A. japonicus is best treated as a regional color variation of the widespread A. nigricans.

Haplotypes of the A. nigricans complex. Each circle represents a unique DNA sequence; larger circles indicate more specimens sharing that sequence. Similar haplotypes are joined by lines. Click to enlarge. Source: DiBattista et al 2016

Also of note is that the Indian Ocean A. leucosternon had six specimens with nigricans DNA, including those from the so-called biogeographic “suture zones” of Cocos-Keeling Island and Christmas Island, where many geminate species pairs are known to overlap and crossbreed. Additional specimens were found from Diego Garcia, part of the Chagos Archipelago in the Central Indian Ocean, where a small population of A. nigricans was recently discovered. And, lastly, a single specimen with apparent hybrid genetics was found in the Seychelles, a portion of the Indian Ocean far removed from where we find A. nigricans, illustrating how hybridization can spread beyond the “suture zones” via larval dispersal.

Hybrids (right row) formed by A. nigricans (left row). Source: DiBattista et al 2016

When we calibrate the amount of genetic divergence that has taken place in this species group, it appears that the split between the Indian Ocean Powder Blue Surgeonfish and the Pacific Ocean Powder Brown Surgeonfish was in the Pleistocene, some 600,000 years ago. The Achilles Surgeonfish, as we might expect from its ecological differences and geographic overlap with A. nigricans, represents an earlier split in this species complex. We also find evidence for considerable expansion of all these populations during the last 100,000-280,000 years, and, even in Hawaii, a region known for encouraging endemic species, A. nigricans is little different in its genetics, suggesting the population there has had little time to diverge from neighboring regions.

A. nigricans seen in Diego Garcia, Chagos Archipelago, a likely recent westward range extension. Source: Craig 2008

It’s interesting to ponder where these various species are heading. Given that the sea levels of our planet are forecast to rise, what impact might this ultimately have on the ability of these species to expand their ranges and interbreed. Might there someday be A. nigricans further west in the Indian Ocean or Powder Blue Tangs in the Pacific, and, if so, would they continue to exist as separate “species” or might they instead homogenize through hybridization. And what of A. japonicus—how did this distinctive phenotype come to be and where is it going? Are we witnessing the birth of a species or its slow demise at the hands of the more widespread A. nigricans. Answers to such questions might ultimately require a time machine, and, alas, Two Little Fishies doesn’t yet sell one for aquarists.

0 Comments