Most of the marine fish hybrids we have seen are from pelagic spawners (fish that broadcast sperm and egg into the water current). Think: dwarf angels, tangs, and butterflyfish. In the ocean, this type of hybridization is the result of blind luck. Every now and then, the eggs of one species will randomly encounter and get fertilized by the sperm of another genetically similar species who happens to be in the “right” place at the “right” time.

Rarely do benthic spawners (fish who lay eggs on substrate) hybridize, and rarer still do benthic spawners who guard their nests until hatching. There’s a perfectly sensible reason for this. Almost all benthic, egg-laying females will see and interact with the males who fertilize their eggs, and a female of one species would be hard pressed to allow the male of another species fertilize her eggs. For example, a female nigripes clownfish is much more likely to kill a male clarkii than to let it father her offspring.

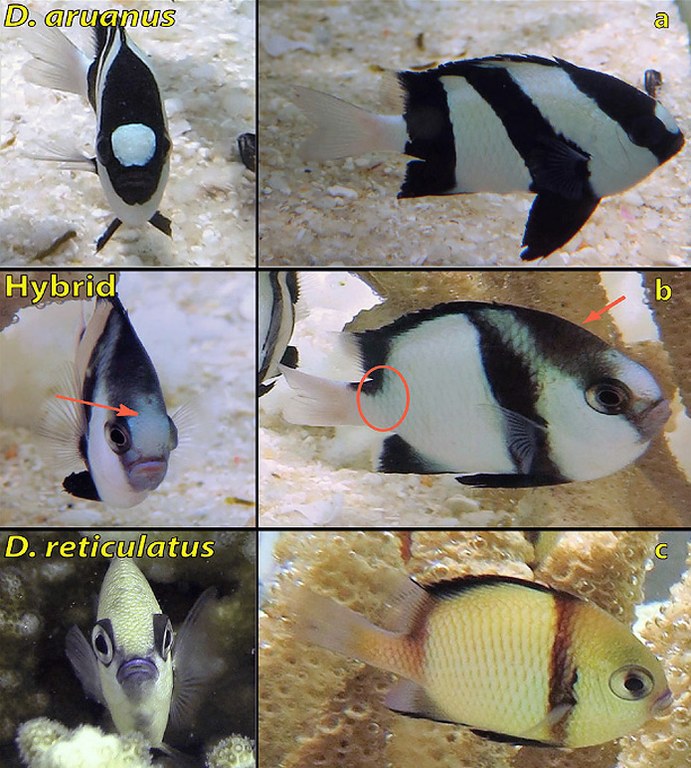

This is why the recent discovery of a hybrid between Dascyllus aruanus and D. reticulatus is so cool. Of the 385+ species of damselfish, only four confirmed hybrids have ever been documented.

This rare hybridization between benthic nesters is mostly a matter of necessity. Says the researchers of the Coral Reef paper, damselfish hybrids are “only [known] from areas where one or both species are rare, such as degraded habitats and/or geographic zones of overlap.” When you have a limited access to breeding partners within your species, you’ll pass on your genes any way you can, including hooking up with a different species.

It’s sort of like the fish version of “love the one you’re with.”

0 Comments