I grew up with a deep appreciation for the sea. Our family holidays always featured scrambling over the rocky shoreline hunting for interesting critters. As you can imagine, I always took the most commonplace species for granted, yet it appeared the humble limpet, that most boring of animals, holds a seriously surprising secret.

Limpets, for me at least, were the unlovable gastropod that were almost impossible to remove from the rocks unless you sneak up on them and catch them unawares. Once they detect your presence, they cling on pretty hard.

Most limpets (true limpets belong to the order Patellogastropoda, though some references more accurately describe this as a ‘clade’) are smallish animals, with conical, highly robust shells a few inches across. Moist species return to their home patch between their spells of grazing and create a small indentation, known as a ‘scar’, in their home rock, into which their shell adapts perfectly as the rock and shell slowly wear away to create a very predator-resistant seal.

The species I am most familiar with is Patella vulgata, a common species from my region, though there are species found on rocky shores worldwide. When I kept fish, I would often take a few of the animals as treats – as you can imagine, their muscular foot makes for good eating.

In some countries, such as Portugal, limpets are considered a delicacy and I must admit to enjoying them myself, but I digress.

Being grazing herbivores, limpets use a tongue-like structure known as a Radula to scrape away algae from rocky surfaces, or algal tissue from macroalgae, while a few outlying species target seagrass.

The radula of all gastropods (apart from bivalves) is quite a feat of engineering and is covered with microscopic teeth, arranged in various ways that reflect the species’ lifestyle. A quick web search will reveal an awful lot of complicated information about teeth direction, layers and so on. What amazes me though is the substance limpets use.

According to a paper from two years ago, (which I can’t believe I missed), the teeth of limpets are made from the strongest known biological material.

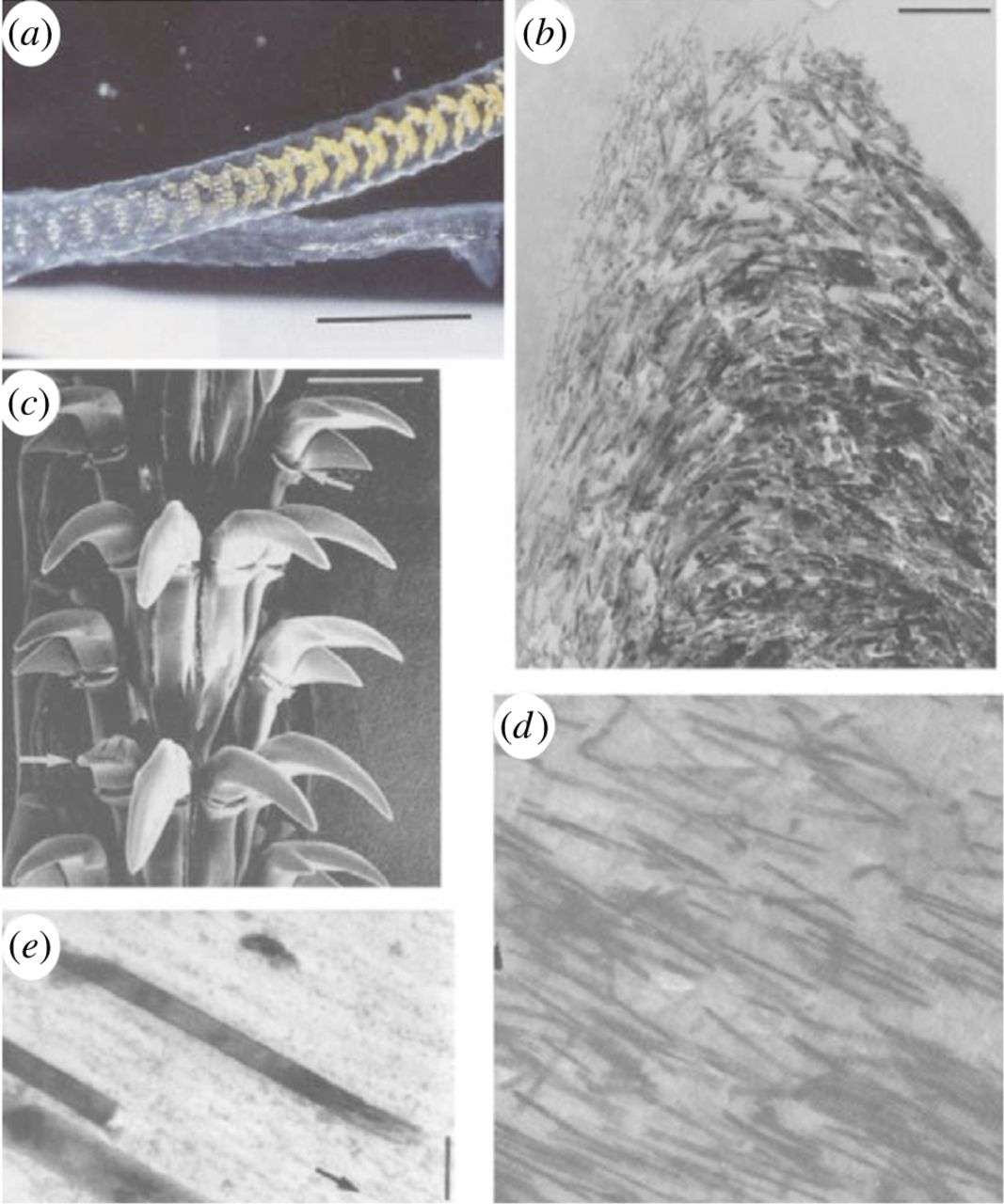

Structure of the common limpet tooth (Patella vulgata). (a) Optical image of the tongue-like radula containing bands of teeth along a length of many centimeters. (b) Scanning electron micrograph of the teeth groupings with each tooth length approximately 100 μm. High-magnification electron microscopy images of the tooth cusp show (c) the changing orientation of the nanofibrous goethite in the chitin matrix and (d) the high anisotropy of the composite at the anterior and posterior edges owing to alignment of the goethite, note the mineral fiber length of approx. 3 μm, with (e) close-up of the tooth indicating the distinct phases of the goethite ‘reinforcing fiber’ and the chitin ‘matrix’ highlighting the structural resemblance to a fiber-reinforced composite material with an average fiber diameter of approx. 20 nm

Material scientists have long known that spider silk is seriously impressive, with a tensile strength that exceeds that of steel and is comparable with some of the most up-to-date carbon fibers. Limpet teeth go further! This is achieved by the remarkable nano structure of limpet teeth which employs goethite nanofibers. Goethite is a mineral containing iron which when combined with the chitin (a very tough protein) in the limpet’s teeth gives these often-overlooked creatures a remarkable claim to fame.

Read more:

http://rsif.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/12/105/20141326

Very insightful. Long live limpets!