Nestled within the family Chaetodontidae is a complex of butterflyfish with a particular proclivity for deep reefs in the mesophotic twilight zone. They share a pattern of alternating broad brown and white bands, and possess a distinctive ocellus on the posterior soft dorsal fin. In stark contrast to most other shallow water representatives, this retiring and reclusive group receives little attention, owing to their penchant for the dreary depths. Specimens are most often seen as bycatch from commercial trawler fisheries, where they are regarded as trash species of no commercial value. With careful elucidation, however, the intriguing beauty of this group becomes evidently apparent, and in the recent decade, has garnered much attention from butterfly “a-fish-cionados”. These banded beauties are members of the genus Roa, and in this article, we explore the intricacies that besiege this group.

Roa suffers from a rather giddying state of taxonomic limbo. R. modesta was the first of its kind known from the subtropical waters of Japan. However, Temminck & Schlegel first described the species in 1844 as Chaetodon modesta. Almost a century later in 1921, Jordan described a similar looking species from Hawaii. He noticed several key differences in morphology from the standard Chaetodon, and subsequently described the Hawaiian specimen as Roa excelsa. Chaetodon modesta was later moved to the new genus Roa, and in 1939, Roa jayakari was described based on trawled specimens from the Indian Ocean. In 2004, Kuiter described Roa australis from the Northwestern Australian shelf and the Arafura Sea, bringing the total species count to four.

Most authors have considered Jordan’s genus Roa to be nothing more than a subgenus of Chaetodon, with various literatures switching back and forth between the two. However, in 1989, Blum reinstated Roa back to generic status based on an unpublished cladistic analysis in his PhD thesis. Ferry-Graham et al. (2001) concurred with Blum’s data analysis, and came to a consensus that Roa was a monophyletic group comprising of three species distinct from Chaetodon. This elevation of Roa to genus level was agreed upon by Pyle (2001) and Kuiter (2002) as well. In this article, we follow the agreed upon classification of Roa at genus level.

The Roa butterflies are most frequently found at depths exceeding 100m, and because of this, are very poorly known by divers and taxonomists. Currently, four species are scientifically recognized, with a handful of other undescribed members distributed throughout the Indo-Pacific. It is also interesting to note that although hybridization in this genus has not been documented, it should not be discounted. In this article we present possible hybridization scenarios as a hypothesis for several unexplained phenotypes with aberrant biogeographical distributions.

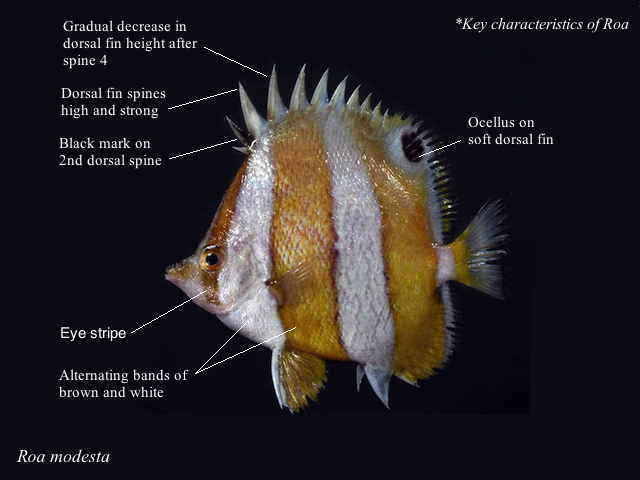

Roa can be easily distinguished from the other butterflyfishes by the following shared traits.

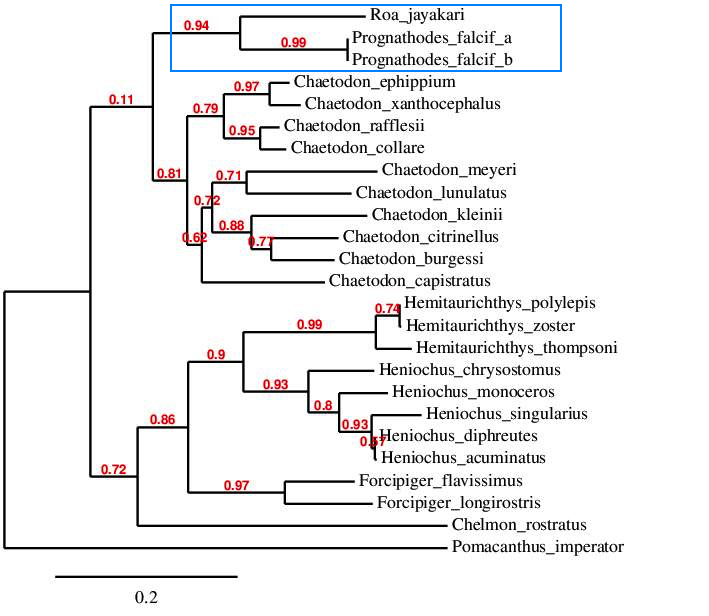

1) The dorsal fin spines are high and strong, generally increasing in size from spines 1-3, and then decreasing in height from 4 to the last. This dorsal finnage bears strong resemblance to those seen in members of Prognathodes and Roaops. While genetic analysis has shown strong support for Roa alongside Prognathodes, it remains distant from the Roaops subgenus of Chaetodon. This should come as no surprise, as Roaops means “Roa-like”, at least in physical attributes.

2) All species of Roa possess eleven dorsal spines, and more than 42 perforated scales of the lateral line. Roaops, in comparison, possess 13 dorsal spines and less than 40 perforated lateral line scales.

3) Roa are some of the more distinctively patterned butterflyfishes, with their design largely based on broad, alternating bands of brown and white.

A CO1 tree showing the strong genetic support of Roa alongside Prognathodes, but weak in comparison to Chaetodon. Photo credit: Joe Rowlett.

All Roa species, with the exception of R. modesta, are strictly deepwater. They frequent deep drop offs in excess of 100m, where they are often found singly or in pairs. They have also been documented at depths exceeding 200m (660ft) by underwater submersibles, making those some of the deepest records known for any butterflyfish species. As such, their infrequent cameos in the aquarium trade are a direct correlation to their reclusive and retiring nature. Only R. modesta and R. excelsa are offered to the trade with some irregularity and extreme dichotomy in value — The former a cheap, often unwanted species, and the latter a highly prized and one of the most expensive butterflyfish species available.

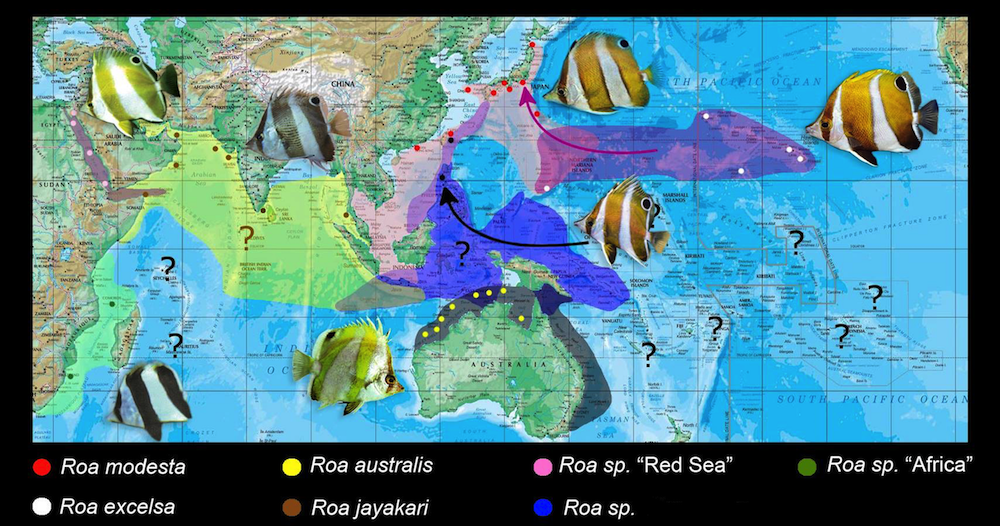

The genus forms a monophyletic group with four recognized members, but is likely to increase in species count with the discovery of potentially new, undescribed specimens. In many aspects, Roa draws similarities to the Roaops butterflies, especially in its somewhat bizarre and aberrant biogeography. They range from Africa to Hawaii, but are curiously absent from Micronesia and the French Polynesia. In all likelihood, the absence of Roa in the Central Pacific and Polynesian islands could be attributed to their elusiveness and penchant for deep waters, and so their presence there should not be fully discounted.

The distribution and biogeography of the genus Roa. The absence of this genus in the Central Pacific and Polynesian chain could be attributed to lack of extensive surveys. There is little doubt that the genus persists in deep waters there. Map courtesy of Joe Rowlett and Jeff Saurwein.

Roa modesta

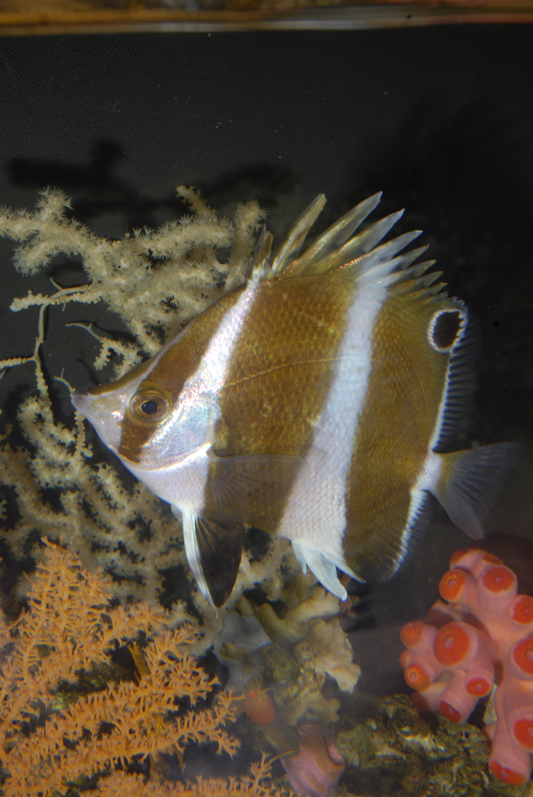

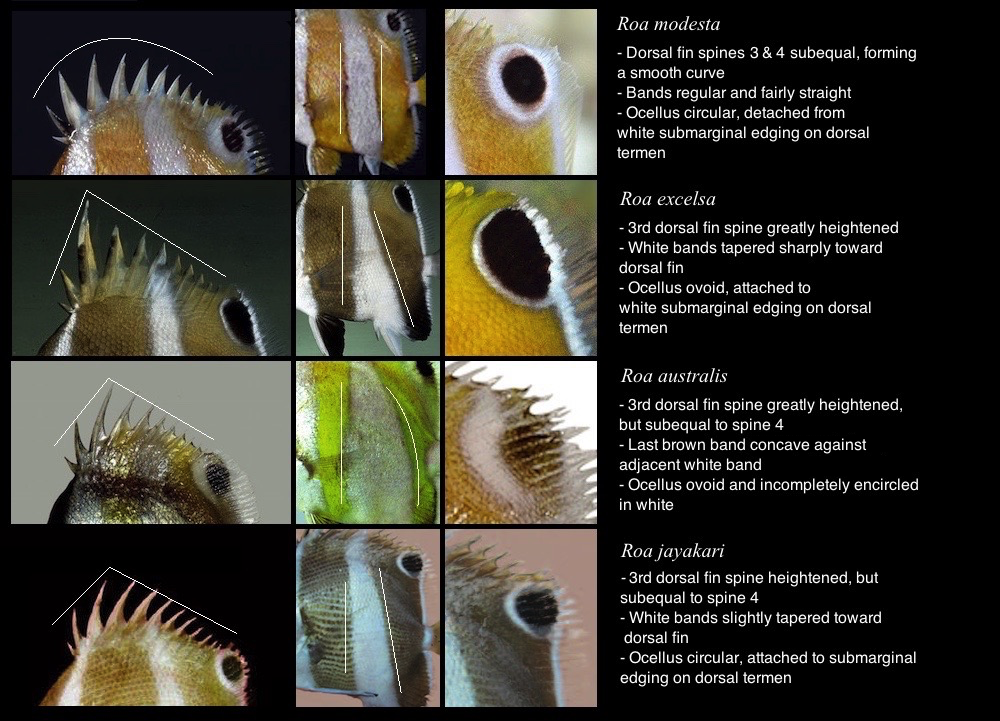

This is the most frequently encountered species of the genus, immediately recognized by its characteristic markings. In Roa modesta, the ground coloration is creamy white with alternating bands of ochre. These bands are relatively consistent in width throughout its length, and are always margined with dark brown. The vertical banding rarely, if ever, extend into the spinous portion of the dorsal fin. The dorsal spines are otherwise whitish to clear, except for the second, which is always marred by a black smudge. In R. modesta, these spines are not exaggeratedly heightened, and form a smooth curve following the contour of the dorsal fin when viewed from the side.

A single large ocellus encircled in white is present on the posterior soft dorsal fin. This ocellus is variably shaped, but is most often circular to very slightly oblong. It maintains a clear distinction from the faint and sometimes absent submarginal white edge of the dorsal fin termen. Together, these characteristics are notably exclusive to Roa modesta, and serves to distinguish it from the other more confusingly similar species – however, it is curious to note that while this species is easily separated from the other Roa, it is often confused for Chelmon or Coradion.

Roa modesta, aquarium specimen. Take note of the darkened margins bordering the ochreous bands. Also note the faint to vestigial white submarginal edge of the soft dorsal fin termen, in which the ocellus maintains distinction from.

R. modesta is found in subtropical waters of Japan, south to Taiwan and Hong Kong in the South China Sea. There are records of this species being found in the Philippines, but in all likelihood, it may only extend to the northernmost tip of Cagayan, where it compensates for the warmer waters by swimming at greater depths. Records from the main Philippines archipelago and the Coral Triangle may allude to a different, potentially new and undescribed species. Because of the cooler, subtropical climate in which it occurs, Roa modesta can be found at depths as shallow as 10m (30ft). However, like all Roa, it has a general proclivity for deeper waters, and is usually found in excess of 100m (300ft).

A juvenile Roa modesta. Take note of the yellowish ochreous banding and the black smudge in the second dorsal spine. Photo credit: Goo.

This biogeography makes Roa modesta the only species in the genus to penetrate shallow water, putting it in close contact with human activity. As such, this species is the most frequently photographed, trawled and collected species of Roa, making regular appearances in both commercial and aquarium fisheries. The former regards this species as a worthless bycatch of zero value, and in the latter, the species is collected only for the domestic market of Japan, Taiwan and Hong Kong, where it retails for a very affordable and measly rate. Despite the unpopularity of Roa modesta in its regional market, the species is regarded as an exotic and highly prized species in the Western world. A classic tale of one man’s trash serving as treasure to another.

This species adapts poorly to captivity, and often fails to thrive unless provided with cooler temperatures. Its difficulty is often compounded by its unwillingness to accept prepared food.

Roa excelsa

Roa excelsa in captivity. Take note of the extremely elongate third dorsal spine. Photo credit: Kengo Zeze, BlueHarbor.

This is arguably the most attractive of the Roa. In this handsome species, the ground coloration follows that of the standard Roa template, but with a few modifications. The white bands are stark, pearlescent, and very narrowly tapered toward the dorsal fin. The brown bands are goldenrod dorsally, darkening gradually to black toward the ventral region. This dark suffusion imparts a caramelized hue, reminiscent of the burnt sugar layer on top of a crème brûlée. The bands lack any prominent borders or margins. The pelvic fins are black, sans the spinous portion in white.

This species is noteworthy for the very exaggerated extrapolation of its third dorsal spine. The specific epithet “excelsa” is latin for elevate, or height, in reference to this feature. Because the spines are so long, and the membranous sheaths are so strikingly colored, the fish takes on a cockatoo like appearance when it raises its dorsal fin. The posterior soft dorsal is marked with the usual ocellus, but unlike R. modesta, it is prominently ovoid and bean shaped. This ocellus never maintains any distinction from the submarginal white edge on the termen of the soft dorsal fin, and fuses with it on the outer circumference.

Roa excelsa in captivity. Note the extensive golden hue in this specimen. Also take note of the oblong dorsal ocellus, and the fusion of its outer circumference with the white submarginal edge on the dorsal fin termen.

Roa excelsa is the allopatric endemic of the genus, found primarily in the Hawaiian archipelago. There are records of this species in Guam, but these are most likely waifs that settle there during juvenile recruitment. As mentioned in the introduction, Roa share many parallels with Roaops in its biogeography. Its Roaps equivalent here is Chaetodon tinkeri – another Hawaiian endemic with stray records in Guam. In the Mariana Arc, it is hypothesized that C. tinkeri hybridizes with C. burgessi to form the rare, hybrid derived Chaetodon flavocoronatus.

While no other Roa has been documented from the Mariana Arc, an unusual phenotype is found in the Izu Peninsular just north of the Marianas. Whether this phenotype is hybrid derived from R. excelsa reaching the Izu Peninsular is unknown, but it would explain the otherwise aberrant appearance of a second phenotype distinct from R. modesta in the Japanese region. If this hypothesis proves to be correct, then this could be seen as a parallel to the relationship between C. tinkeri and C. flavocoronatus in the Marianas. This will be further elaborated later on in the article.

Roa excelsa in captivity. Take note of the white banding reaching well into the dorsal spine. In R. modesta, the bands never reach the spines.

Roa excelsa is strictly deepwater, and is found only in depths exceeding 100m (300ft). It becomes most apparent at 400ft, occurring either singly or in bonded pairs. The preferred habitat for this species includes inclined drop offs and ledges permeated with holes, often in the company of Prognathodes and Odontanthias. In the cooler northwestern islands of Hawaii, this species can be found at significantly shallower waters of around 200ft.

The presence of Roa excelsa in captivity is of a somewhat curious nature. It wasn’t only until the last decade that this species gained any significant prevalence in the aquarium industry. Although still rare, the availability of rebreather-collected fish from the Hawaiian Islands has since provided the world with a glimpse of this highly elusive and decadent species. This makes R. excelsa the only other Roa available to mainstream aquarists aside from R. modesta.

While the extreme depths and utilization of rebreather diving justifies the high cost of this species, it is essentially just a sleeker, more attractive version of the humble R. modesta. In comparison of the two available Roa, we see a highly perplexing dichotomy in perceived value – a fish inspiring highly coveted lust, versus one of inconsequential worth. Unlike R. modesta however, R. excelsa has a comparatively better track record in aquaria.

Roa australis

The holotype of Roa australis. Note the concavity in the last brown band. Photo credit: Barry Hutchins.

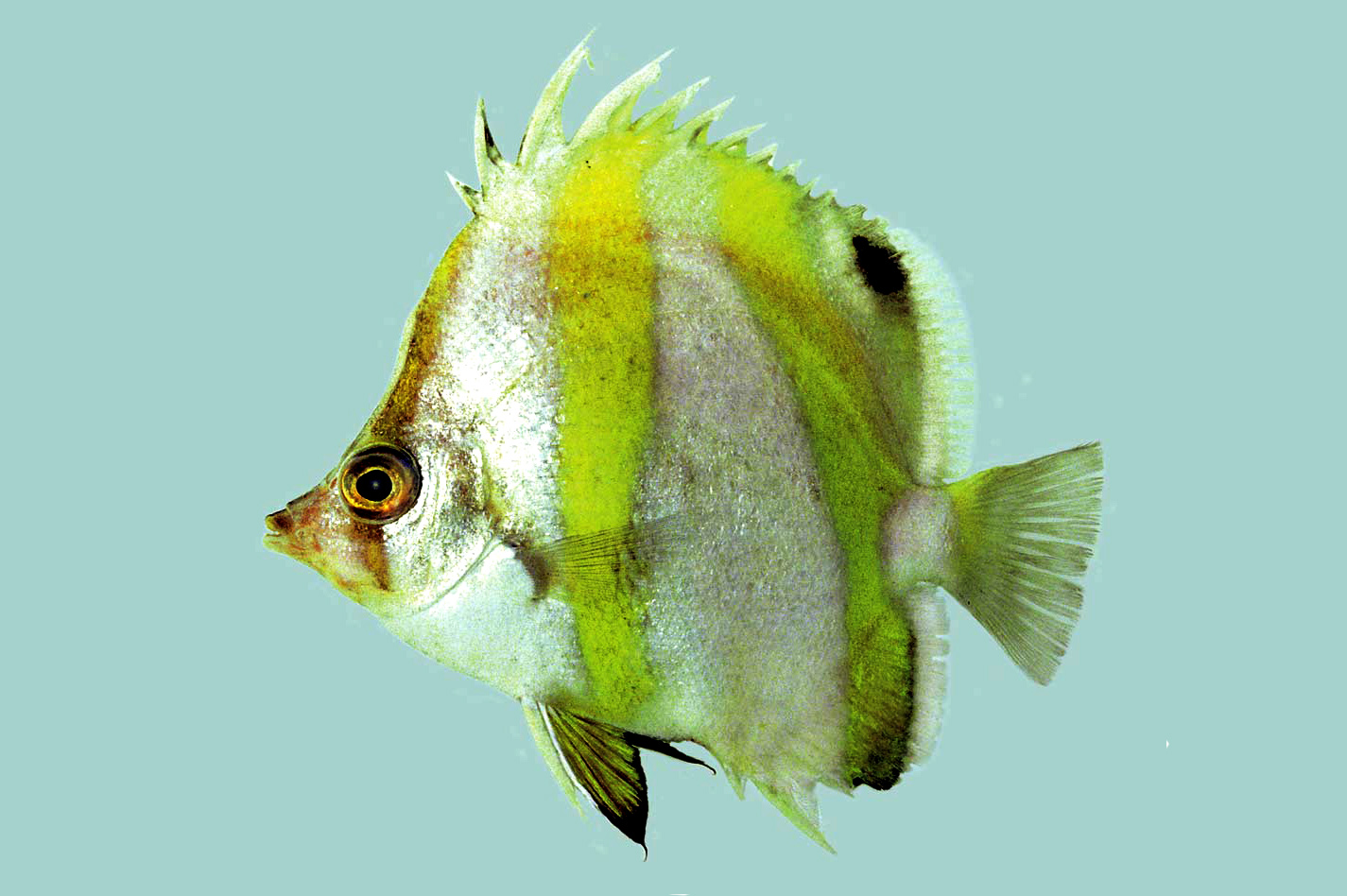

Described in 2004, Roa australis is the newest addition to the genus. The specific epithet “australis” comes from the Latin word for south, in reference for its distribution in the Southern Hemisphere. Roa australis follows the typical banded appearance of its congeners, but is immediately recognized by having the last brown band flexed in a gentle concavity against the adjacent white band. The bands also appear to be slightly more yellowish-ochre, although this should be subjected to more careful scrutiny, seeing as no living photos of this fish exists.

The third and fourth dorsal spines are noticeably subequal and less exaggerated compared to Roa excelsa, but show greater prominence than those seen in R. modesta. All the spines are white, with the brown banding never infiltrating past the base. Roa australis shows variability in the amount of black smudging present on the second dorsal spine. It appears to be weakly present, although the post mortem photographs of this species fail to accurately elucidate this feature. As with all Roa, an ocellus is present on the posterior soft dorsal fin, and in R. australis, is oblong, and never fully encircled in white.

Roa australis. Take note of the oblong dorsal ocellus and the incomplete encircling of white. Photo credit: Martin Gomon.

Roa australis. Take note of the white dorsal spines, and the concavity of the last brown band. Photo credit: Australian National Fish Collection, CSIRO.

Roa australis is found in the Southern Hemisphere, specifically around the northwestern shelf of continental Australia and the Arafura Sea at depths between 100-120m. It is a poorly known species, and seen mostly as bycatch from trawler fishing. There is little doubt that its distribution encompasses more than what is currently known. During its description, it was regarded as the only member of the genus Roa to occupy Earth’s Southern Hemisphere (hence its name). However, a second species has been documented inhabiting deep trenches in Africa at the same latitude as Roa australis, making the title now defunct.

This species has never been, and will quite likely never be offered for the aquarium trade, unless its range extends to collection prone areas of Australia, where deepwater divers descend. In all likelihood, its biology and habitat remains similar to those of R. excelsa and R. modesta.

Roa Jayakari

Roa jayakari. A trawled specimen from 106m in the Gulf of Mannar, India. This locality represents a new record for the species. Photo credit: Vinay P. Padate.

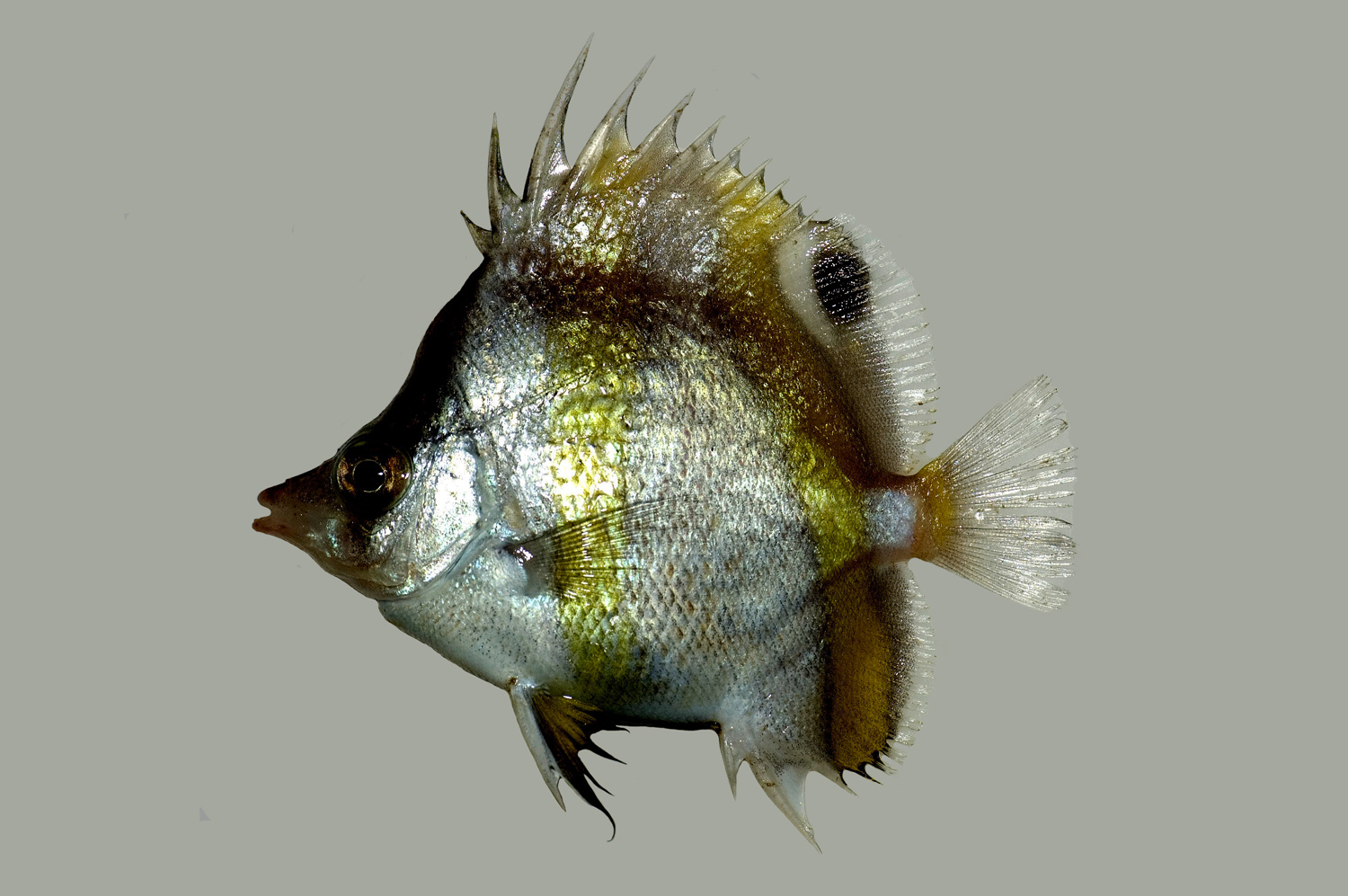

R. jayakari is known mostly from trawled specimens in commercial fisheries, where it is regarded as a useless trash bycatch. It adopts the same template, with white and brown alternating bands. The bands are cinnamon brown, matte, and without any yellow or gold suffusion like in the previous three species. The white banding tapers slightly toward the dorsal fin, but are never as narrow as those seen in R. excelsa. The third dorsal fin spine is longer than the first and second, subequal to the fourth, and are colored as with the band patterns on the body. An ocellus is present on the soft dorsal fin, is round, encircled in white and merged with the submarginal white edge on the dorsal termen. The snout is suffused on the upper lip region in brown, but whether or not this is a post mortem artifact remains unclear.

Roa jayakari from the Andaman Sea. A trawled specimen from the fish market in Thailand. Photo credit: Ohm Pavaphon.

Roa jayakari from Mangalore, India. Notice the brown suffusion on the upper rostrum. Photo credit: Raju Saravanan.

The biogeography of Roa follows very closely to those seen in other reef species, showing speciation within the intangible boundaries of the various endemic ecoregions. R. jayakari is well represented in the Indian Ocean, from the Andaman Sea, to Pakistan, India, Oman and the Gulf of Aden. This species is also recorded from the Red Sea, but in following the biogeographic regions of endemism, there is a possibility that the population within may represent a different species, or at least one in the incipient stages of speciation.

In 2013, a specimen was obtained from a benthic trawl at 106m in the Gulf of Mannar, India. This represented a new locality for the species, putting it at the southernmost point of the Indian subcontinent, adjacent to Sri Lanka. The Maldives archipelago lies just 620 miles south of this region, and is known to harbor unique and endemic fauna. In some of the shallow water species such as Cirrhilabrus, we find endemic species otherwise absent on the Indian subcontinent. However, Roa jayakari, with its penchant for deep waters and longer larval development, should be expected to occur unchanged in the Maldives, using the Chagos-Laccadive Ridge as a connection between the two regions.

The four scientifically recognized species are easy enough to diagnose based on the diagram above. Identification gets a little trickier between the potentially undescribed members later on in this article.

Roa cf. jayakari (Red Sea)

The Red Sea population of Roa jayakari from the Gulf of Aqaba and Eilat respectively. Photo credits: Jürgen Schauer and Tony Malmqvist respectively.

The Red Sea examples of Roa jayakari is superficially indistinguishable from the main population. It appears to have a completely white rostrum, versus the brownish tinged upper snout in those coming from the Indian Ocean. However, because no living photos of R. jayakari from the Indian Ocean has been recorded, and likewise no dead photos of R. jayakari from the Red Sea are available, this comparison cannot be used with any confidence or certainty. In all likelihood, the darkening of the snout could be a post mortem artifact.

The only semi-reliable basis that the two populations differ in any way should be with regards to their biogeography. The Red Sea is a well-studied ecoregion with a high number of endemics. Cold, nutrient-rich water barriers and constriction of the straits separating the Red Sea from the Gulf provides potential isolation barriers from the rest of the Indian Ocean. Together with glacial cycles throughout the various epochs, these factors drive the divergence of reef fish populations via a combination of isolation and natural selection. Endemics within the Red Sea usually have a corresponding sister species outside, and although not confirmed, may occur in Roa jayakari as well. Seeing as all members of Roa show no significant differences in meristic value, a thorough and very extensive genetic analysis is required to see if population divergence is occurring between the two R. jayakari populations.

Roa sp. (Africa)

Roa sp. Underwater submersible photograph of a specimen in Leadsman Canyon, Swaziland. Photo credit: ISpotNature.

A supposedly undescribed species of Roa occurs in the Eastern and South African coast. Unlike the typical brown and white bands, this fish sports a monochromatic appearance of black and white. The pelvic fins and the supporting rays are entirely black, and the bands travel well into the spinous portion of the dorsal fin. Only a few photos of this peculiar fish exist, mostly from underwater submersibles at depths exceeding 200ft.

This fish is reported from Swaziland and the Comoros. A single specimen is located in the California Academy of Sciences, where it is awaiting official description.

Roa sp. (?) (Philippines/Coral Triangle)

In late 2013, the Association for Marine Exploration under a University of Hawaii expedition in the Philippines revealed the presence of a previously unknown, deepwater Roa species. In April 2014, the same Roa was sighted again in a separate expedition conducted by the California Academy of Sciences in Anilao, Batangas. Numerous specimens were collected in both instances, but were initially erroneously identified as R. modesta. It was only later that the identity was confirmed, when the biogeography, morphometrics and color analysis turned out distinct from those of R. modesta.

The ground coloration is typically banded, with the brown bands taking on a dark, russet undertone, and the white tapering slightly to the dorsal fin spines. The third dorsal spine is sharply elongated in comparison to the second, making this species immediately distinct from R. modesta. The second spine is marred in black, and the rest follows the banded patterns of the body. A single, well-defined ocellus is present on the posterior soft dorsal fin. This ocellus is rounded and encircled completely in white, where it merges with the submarginal white edge of the dorsal fin termen.

In comparison to R. modesta and R. excelsa, a few significant differences can be observed.

1) The third dorsal fin spine is greatly elongated and subequal to the fourth, versus a smooth elongation gradient in R. modesta. The bands on the body are dark, slender and tapering, versus the yellowish-ochre and rectangular form in R. modesta.

2) The dorsal fin ocellus is circular versus ovoid in R. excelsa. The second dorsal fin spine is prominently marred in black, versus absent to highly vestigial in R. excelsa.

Brian Greene with the new Roa in a collection jar. Anilao, Batangas, 2013. Photo credit: Robert Whitton.

Roa sp. with other Philippine fishes from the 2014 expedition conducted by the California Academy of Science.

Like the rest of the genus, this Roa frequents deepwater habitats in excess of 100m. Dr. Luiz Rocha reports seeing them at 400ft, and Brian Greene collected numerous specimens at 450ft, along with Odontanthias, Sacura and Liopropoma – a familiar set of fish often accompanying Roa at depth. It is known currently only from the Philippines, in Anilao, but its distribution is likely to encompass a much wider region.

Reports of Roa modesta occurring in the Philippines could be based on these potentially undescribed specimens instead. If R. modesta should in fact stray to the Philippines, the species should be looked for in the northernmost tip of Cagayan, and it is unlikely to occur past Luzon to the south. Whether or not this “new” Roa is found up north in the company of R. modesta is unclear, and how extensive its distribution is in the Philippines is likewise also unknown.

This phenotype is the precursor to a complicated scenario of two other highly similar, nearly indiscernible Roa found further north in Taiwan and the Izu region of Japan. Whether these are all the same fish is currently unknown.

Roa sp. (?) Taiwan

An unknown Roa collected in Taiwan. Notice how it is virtually indistinguishable from the Philippine species. Photo credit: Victor Wong.

Records of an unknown Roa occurring in Taiwan have been reported from fish collectors in the region. Interestingly, these look nearly identical to the preceding specimens from the Philippines. Whether or not they are the same remains unclear. Here, it is sympatric with Roa modesta, and the two are occasionally trawled together in fisheries. Both adults and juveniles have been caught on a semi-regular basis, suggesting that these are not waifs, but are indicative of a resident population. These are, however, always rarer than R. modesta.

Roa sp. (?) and Roa modesta from Taiwan. Notice immediately how the two differ in coloration and patterns. Photo credit: Victor Wong.

An adult Roa sp. (?) from Taiwan. Notice how this fish bears an almost identical resemblance to the ones from the Philippines. Are these the same? Photo credit: Formosa Fish.

Roa sp. (?) (Izu, Japan)

This similar phenotype appears again in Japan, but is restricted only to the Izu island chain, just north of Ogasawara and the Marianas. Are these indicative of one species, extent throughout Izu, south to Taiwan and the Philippines? If these are indeed the same “species”, does that mean the Coral Triangle phenotype hasn’t been found yet?

Although contentious, another hypothesis involving hybridization with Roa excelsa could possibly explain the Izu phenotype. In the Mariana Arc, Chaetodon flavocoronatus is hypothesized to arise from the hybridization of C. tinkeri and C. burgessi – the former as a waif from Hawaii, and the latter, a rarely occurring species there. Roa excelsa has been documented in Guam, suggesting that juvenile recruitment in the Mariana Arc influenced by eddies and an oceanographic currents is possible. In this instance, could a parallel be drawn between Roa and Roaops?

Should R. excelsa waif just slightly north into the Izu archipelago, it would put it in close proximity with Roa modesta. Could the hybridization of both species yield the formation of the Izu Roa phenotype? Possible, but definitely not conclusive.

To fully make sense of this genus, biogeography and extensive genetic comparison are needed to draw any substantial conclusions. However, the deepwater and elusive nature of Roa makes this one of the most inscrutable genera of butterflyfish to date. Until enough specimens and distribution information can be provided, the genus Roa shall remain shrouded in a miasmic haze of uncertainties.

Roa sp. in captivity. The collection location for this specimen is unknown. Could it be Japan, Taiwan or the Philippines? The similarities between specimens from all three locale is too inscrutable to discern. This begs the question. Are they all the same? Photo credit: Unknown.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Dr. Luiz Rocha, Brian Greene, Rufus Kimura and Joe Rowlett on their insightful thoughts regarding this topic. Also special thanks to Joe Rowlett and Jeff Saurwein for the creation of the distribution maps in this article.

References:

DiBattista, J. D., Howard Choat, J., Gaither, M. R., Hobbs, J.-P. A., Lozano-Cortés, D. F., Myers, R. F., Paulay, G., Rocha, L. A., Toonen, R. J., Westneat, M. W. and Berumen, M. L. (2015), On the origin of endemic species in the Red Sea. Journal of Biogeography. doi: 10.1111/jbi.12631

Kuiter, Rudie H., 2004. Description of a new species of butterflyfish, Roa australis, from northwestern Australia (Pisces: Perciformes: Chaetodontidae). Records of the Australian Museum 56(2): 167–171.

Great work Lemon!