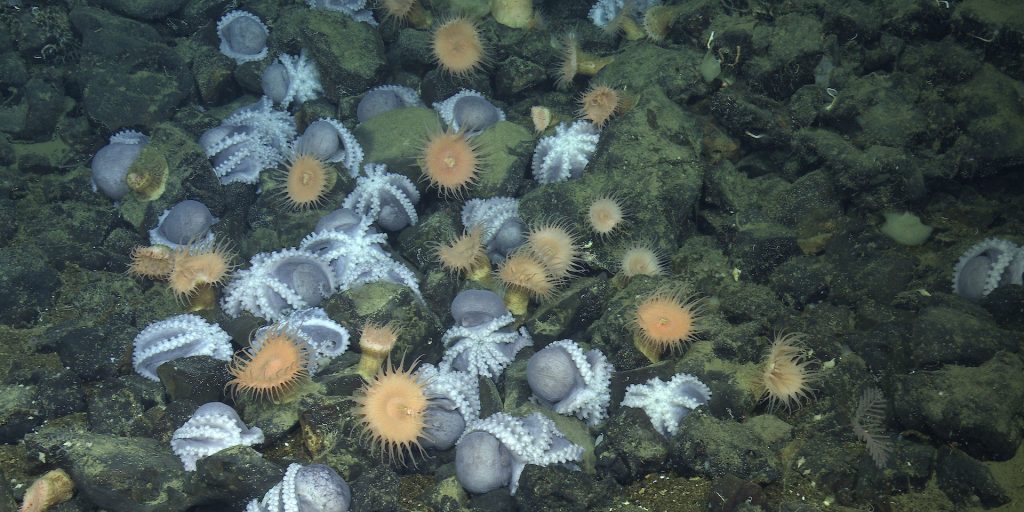

For three years, MBARI and collaborators monitored the Octopus Garden with high-tech tools. The team learned that large numbers of pearl octopus (Muusoctopus robustus) gather at this site to mate and nest. Image: © 2022 MBARI

In 2018, researchers from NOAA’s Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary and Nautilus Live observed thousands of octopus nesting on the deep seafloor off the Central California coast. The discovery of the “Octopus Garden” captured the curiosity of millions of people around the world, including MBARI scientists. For three years, MBARI and collaborators used high-tech tools to monitor the Octopus Garden and learn exactly why this site is so attractive for deep-sea octopus.

In a new study published today in Science Advances, a team of researchers from MBARI, NOAA’s Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, the University of Alaska Fairbanks, the University of New Hampshire, and the Field Museum confirmed that deep-sea octopus migrate to the Octopus Garden to mate and nest. The Octopus Garden is one of a handful of known deep-sea octopus nurseries. At this nursery, warmth from deep-sea thermal springs accelerates the development of octopus eggs. Scientists believe the shorter brooding period increases a hatchling octopus’ odds for survival. The Octopus Garden is the largest known aggregation of octopus on the planet—researchers counted more than 6,000 octopus in a portion of the site and expect there may be 20,000 or more at this nursery.

At the Octopus Garden, pearl octopus (Muusoctopus robustus) mothers nest in rocky crevices bathed by hydrothermal springs. The warmer water accelerates the development of octopus eggs. Image: © 2020 MBARI

The Octopus Garden is located 3,200 meters (10,500 feet, or about two miles) below the ocean’s surface on a small hill near the base of Davidson Seamount, an extinct underwater volcano 130 kilometers (80 miles) southwest of Monterey, California. The site is full of Muusoctopus robustus—a species MBARI researchers nicknamed the pearl octopus because from a distance, nesting individuals look like opalescent pearls on the seafloor.

When researchers from NOAA and Nautilus Live first discovered the Octopus Garden, they observed “shimmering” waters. This phenomenon occurs when warm and cool waters mix, suggesting the region had previously unknown thermal springs. Further investigation by MBARI researchers and their collaborators confirmed octopus nests are clustered in crevices bathed by hydrothermal springs where warmer waters flow from the seafloor.

The ambient water temperature at 3,200 meters (10,500 feet) deep is 1.6 degrees Celsius (about 35 degrees Fahrenheit). However, the water temperature within the cracks and crevices at the Octopus Garden reaches nearly 11 degrees Celsius (about 51 degrees Fahrenheit).

At the near-freezing temperatures of the abyss, researchers expected pearl octopus eggs to take five to eight years, if not longer, to hatch. A 4K camera on MBARI’s ROV Doc Ricketts provided a close-up look at nesting mothers. MBARI researchers and their collaborators used the scars and other distinguishing features of individual octopus moms to monitor the development of their broods. Surprisingly, the eggs hatched in less than two years. Warmth from thermal springs increased the metabolism of female octopus and their broods, reducing the time required for incubation.

Researchers believe the shorter brood period in warmer waters greatly reduces the risk that developing octopus embryos will be injured or eaten by predators. Nesting in warmer water boosts the reproductive success of the pearl octopus, better ensuring the offspring’s survival.

“Essential biological hotspots like this deep-sea nursery need to be protected,” said MBARI Senior Scientist Jim Barry. “Climate change, fishing, and mining threaten the deep sea. Protecting the unique environments where deep-sea animals gather to feed or reproduce is critical, and MBARI’s research is providing the information that resource managers need for decision-making.”

0 Comments