How can coral reefs, one of the most diverse and productive ecosystems on Earth, survive in nutrient-poor tropical waters, like an oasis in a marine desert? That question, also known as Darwin’s Paradox, seems to be answered after 171 years by researchers Jasper de Goeij from the University of Amsterdam and Dick van Oevelen from the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ). With colleagues from the Dutch Universities of Maastricht, Wageningen and Utrecht, and the research institute Carmabi on Curaçao, they published their findings in the renowned journal Science.

The study, led by De Goeij and Van Oevelen, shows that sponges are the missing link between corals and algae and the other inhabitants of the coral reef. Sponges recycle the waste products from corals and algae and convert these into a food source that is accessible to other reef inhabitants. This recycling pathway, termed the ‘sponge loop’ by the research team, explains how energy and nutrients are conserved within the coral reef ecosystem instead of leaking to the surrounding waters of the marine desert.

The Sponge Loop

Sponges are known as impressive filter feeders, feeding on small particles like bacteria, planktonic algae and even virus particles. The majority of their daily diet, however, consists of invisible dissolved organic substances, such as sugars. In fact, these dissolved substances form the largest source of energy and nutrients on coral reefs and are produced by corals and algae. This food source is not available to most other organisms living on the coral reef and may therefore leak to the surrounding tropical seas.

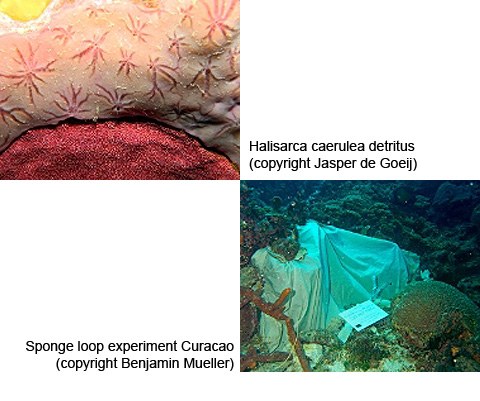

The research team of De Goeij and Van Oevelen has now shown that sponges prevent the leakage of dissolved energy and nutrients and make these resources accessible to other reef inhabitants. They labeled dissolved food, traced it throughout the entire ecosystem and found that sponges took up the labeled food and quickly turned it into detritus, or, in other words: sponge feces. Then, this detritus rains down on the reef where it forms an important food source for other reef inhabitants, like small crabs, snails and worms. These small animals are eaten in turn by larger animals, whereby the originally dissolved food is looped back into the food web. De Goeij and colleagues hereby show that sponges are at the base of a previously unknown recycling pathway – the sponge loop – that plays a pivotal role in the food web of coral reef ecosystems.

The Importance of Sponges

The study led by De Goeij and Van Oevelen emphasizes the role of sponges in future research and management of coral reefs. To date, their role is severely undervalued, while coral reefs, important socio-economic areas for tropical coastal areas, are threatened worldwide. Sponges help us to understand how coral reefs function, but also how these ecosystems can be highly productive, without leaking energy and waste. This knowledge can be applied in the development of sustainable aquaculture and the construction of so-called Integrated Ocean Farms.

De Goeij and Van Oevelen explain the sponge loop and how it leads to the development of sustainable fish farming in the Dutch tv program Labyrint TV (NPO; English subtitle):

0 Comments