Coral, with its porous nature and curled structure, is extremely efficient at absorbing toxic heavy metals; deadly poisons. The mercury that is polluting our oceans is contributing to massive coral die-offs, and is building up in the food chain, eventually resulting in toxic fish. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), between 1.5 and 17 in every thousand children living in selected subsistence fishing populations showed cognitive impacts caused by the consumption of fish containing mercury. Coral’s remarkable ability to absorb heavy metals inspired researchers at Anhui Jianzhu University in China to create nano-sized, coral-like structures that use aluminum oxide to absorb mercury out of the water.

The team, led by Dr. Xianbiao Wang, published their procedures and findings this week in the Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. They outlined their process for creating this unique structure, which they found to be about two and a half times more effective at absorbing mercury than traditionally structured nanoparticles – 49.15 mg/g vs.19.56 mg/g.

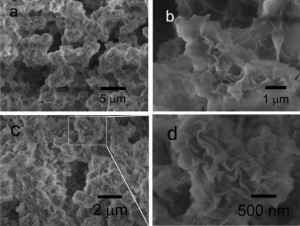

These images show the coral-like aluminum oxide nanostructure, composed of hierarchical small units with sizes of ∼1.5 μm, as well as the curled nanoplates that form on the surface of the units. The pore sizes are in the range of 2–140 nm in diameter.

Beginning with aluminum and hydroxide, the researchers induced a series of reactions to produce aluminum oxide, or y-AlOOH. Al3++3OH–→AlOH3→AlOOH+H2O

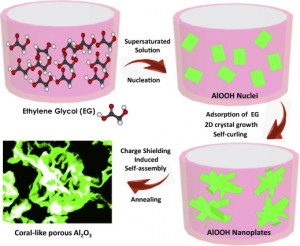

The scientists then created a solution of water, aluminum oxide, and ethylene glycol (EG). When the concentration of γ-AlOOH reached supersaturation, crystal nuclei would be formed in the solution and subsequently grow. The volume ratio of EG to water in the mixed solvent was very important; the results could only be obtained at VEG:VH2O=4:1.

EG is a general capping organic solvent which adsorbed on the surface of γ-AlOOH crystal by hydrogen bonding, leading to preferential, nanoplate-like growth.The surface-adsorbed EG molecules would then inhibit the adsorption of other ions in solution and shield the surface charges (kown as the charge shielding effect). Finally, the charge differences between the nanoplates’ surfaces and edges induced by charge shielding effect drove the structure to form self-curled nanoplates and a coral-like structure.

EG is a general capping organic solvent which adsorbed on the surface of γ-AlOOH crystal by hydrogen bonding, leading to preferential, nanoplate-like growth.The surface-adsorbed EG molecules would then inhibit the adsorption of other ions in solution and shield the surface charges (kown as the charge shielding effect). Finally, the charge differences between the nanoplates’ surfaces and edges induced by charge shielding effect drove the structure to form self-curled nanoplates and a coral-like structure.

To read the full scientific abstract, visit Science Direct.

0 Comments