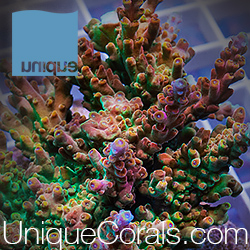

Truth be told, the first time that I saw this photograph I was completely fooled. Surely it had to be a soft coral of some sort… those large fluffy polyps must belong to a xeniid, right?

When I was then told by Cameron Bee at Monsoon Aquatics that it was, in fact, an anemone collected from the shallow waters around Darwin, Australia, it was a revelation. Surely, then, this had to be the Mimic Anemone (Phyllodiscus semoni). That species occurs across the Indo-Pacific and is aptly named for its uncanny ability to camouflage itself by imitating a wide variety of marine life.

According to one study, this includes various stony corals (Acropora, Anacropora, Seriatopora, Pocillopora) and soft corals (Asterospicularia, Efflatounaria, Klyxum, Sinularia, Briarium, Tubipora), as well as variations that resemble algae-covered rocks and perhaps Rhodactis corallimorphs or carpet anemones. This is a species which likes to wear many hats, as they say, but never has it been documented to resemble Xenia.

Phyllodiscus accomplishes this subterfuge with some highly modified pseudotentacles that ring the column of the body. During the day, the anemone keeps itself retracted, and, while in this state, it is only the pseudotentacles that are visible—the true tentacles that surround the mouth, used for feeding, are only revealed at night.

In addition to this remarkable mimicry, Phyllodiscus possesses a devastating toxicity to its venom. The sting is said to be excruciatingly painful and produces a severe dermatitis which takes many months to heal from, but, for an unlucky few, the body undergoes an even more severe and debilitating reaction. The venoms involved will cause acute renal failure, which can result in permanent damage to the kidneys. Given the significant dangers this species poses to our frail mammalian bodies, it is vitally important that we are able to accurately identify it.

Except, this isn’t the Mimic Anemone either, even though it is obviously an anemone that mimics. No, dear reader, I had now been fooled a second time by this enigmatic creature. It was only when I was shown the following photographs that the true nature of this beast became apparent. The diagnostic trait to look for here is the location and number of the nematospheres—those are the grapelike clusters situated along the periphery of the oral disk. In Phyllodiscus, these are smaller and sparser in their distribution and would be attached to the pseudotentacles present on the body column.

Another easily recognized difference is the texture of the column, which is smooth in Phyllodiscus, whereas this specimen is covered in row upon row of non-adhesive verrucae—those are the pimple-like swellings. So, then, what is the true identity of this anemone?

There’s only one genus this can be, Thalassianthus. This obscure little group has historically been very poorly studied, and even now, despite a recent revision, 3 of the 5 recognized taxa are still only known from a single specimen. Aquarists might be familiar with T. hemprichii, a species which looks a bit like a carpet anemone with plumose tentacles. It comes in a variety of attractive colors, often with contrasting purple nematospheres, and can reach up to a foot across. Anemonefishes are known to use it as a host in captivity, though this has never been observed in the wild.

But this Xenia mimic appears to belong to a different species, T. aster. The recent revision to this family makes no mention of any apparent coral mimicry, but others who have photographed it in the wild have noted the obvious resemblance. Compared to the other members of this genus, T. aster is said to be recognized by the circular, non-undulating shape of the oral disk in combination with a reduced density of tentacles relative to T. hemprichii. Others, like the rarely seen T. villosa and T. dendrophora, have a deeply undulated margin.

There’s little documented about the potential potency of this species. The closely related Pizza Anemone (Cryptodendrum adhaesivum) is well-known for the adhesive strength of its tentacles and the tendency it has for preying upon aquarium fishes, but it hasn’t been recorded in the medical literature as being especially toxic. The same likely goes for Thalassianthus; however, you’ll occasionally see this group misidentified in the aquarium trade as a far more dangerous foe, the Hell’s Fire Anemone (Actinodendron plumosum), a name that has also been regularly misapplied to aquarium specimens of Phyllodiscus. These three are very different in their morphology and are classified as belonging to three separate families. Correctly identifying them is important, though, as Thalassianthus is the only safe one of the bunch.

- Ardelean, A., 2003. Reinterpretation of some tentacular structures in actinodendronid and thalassianthid sea anemones (Cnidaria: Actiniaria). Zoologische Verhandelingen, pp.31-40.

- Crowther, A.L., 2013. Character evolution in light of phylogenetic analysis and taxonomic revision of the zooxanthellate sea anemone families Thalassianthidae and Aliciidae (Doctoral dissertation, University of Kansas).

- Hoeksema, B.W. and Crowther, A.L., 2011. Masquerade, mimicry and crypsis of the polymorphic sea anemone Phyllodiscus semoni and its aggregations in South Sulawesi. Contributions to Zoology, 80(4).

- Maeda, M., Honma, T. and Shiomi, K., 2010. Isolation and cDNA cloning of type 2 sodium channel peptide toxins from three species of sea anemones (Cryptodendrum adhaesivum, Heterodactyla hemprichii and Thalassianthus aster) belonging to the family Thalassianthidae. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 157(4), pp.389-393.

- Mizuno, M., Nozaki, M., Morine, N., Suzuki, N., Nishikawa, K., Morgan, B.P. and Matsuo, S., 2007. A protein toxin from the sea anemone Phyllodiscus semoni targets the kidney and causes a severe renal injury with predominant glomerular endothelial damage. The American Journal of Pathology, 171(2), pp.402-414.

- van der Meij, S.E., Draisma, S.G. and Waheed, Z., 2018. Multiple observations of the sea anemone Phyllodiscus semoni Kwietniewski, 1897 (Actiniaria: Aliciidae) from Sabah, Borneo represent first records for Malaysia. Regional Studies in Marine Science, 18, pp.135-138.

0 Comments