Amblyosyllis sp. a beautiful syllid species from the White Sea.

About three years ago, I headed to Chile with my colleague and friend Dr. Patricia Alvarez-Campos. She had received a grant to collect and study polychaete worms in Central Chile. For those of you who don’t know what a polychaete is, think of the gorgeous cousins of your good ‘ol earthworms; polychaetes are annelids, like earthworms and leeches, mostly marine and extremely diverse both in terms of species numbers and body shapes. Many of the readers of Reefs might have had to deal with these marine worms in their aquariums, as they can be introduced in live rock and can eat up all your beautiful corals.

Patricia was completing her doctoral research at the time, studying the biodiversity and reproduction of a group of polychaete worms called syllids. Syllid worms are very diverse, with more than 700 species described so far, and can be found in almost every marine environment, from the shallowest coral reefs to the deepest ocean trenches. They also have a very unique mode of reproduction that is often synchronized with the moon cycle.

We organized an expedition to central Chile and arranged a collaboration with researchers at the Estación Costera de Investigaciones Marinas (ECIM). ECIM is a marine research center with an associated marine protected area that belongs to the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, and it is located in Las Cruces, in the Valparaíso Region. During our time here, we mainly wanted to investigate the diversity of syllid worms in the area. How many species are there? Are they similar to the species we find in other areas of the Pacific Ocean? Are there new species waiting to be discovered?

But discovering new species of worms was not our only focus during this expedition. We were also interested in the reproduction of some particular species of syllid worms. We wanted to know whether reproduction in these species is synchronized with the moon cycle, with which particular phase of the moon, and whether different species are synchronized with different phases of the moon. So we spent over a month collecting polychaetes in different moments of the moon cycle and making observations about their reproductive state.

One night while looking at a specimen under the microscope (they are only a few cm in length and just a couple mm wide) we noticed it had little appendages in the shape of a cup all over its body. These little cups –the very scientific name we gave them– would open and close like an upside down minuscule jelly fish. At first, we thought it was some kind of filter feeding mechanism or a sensory appendage, but we had never seen anything like that before. The little cups were a mystery to us. After observing them carefully and speaking with a couple of colleagues, we realized that they were actually symbionts.

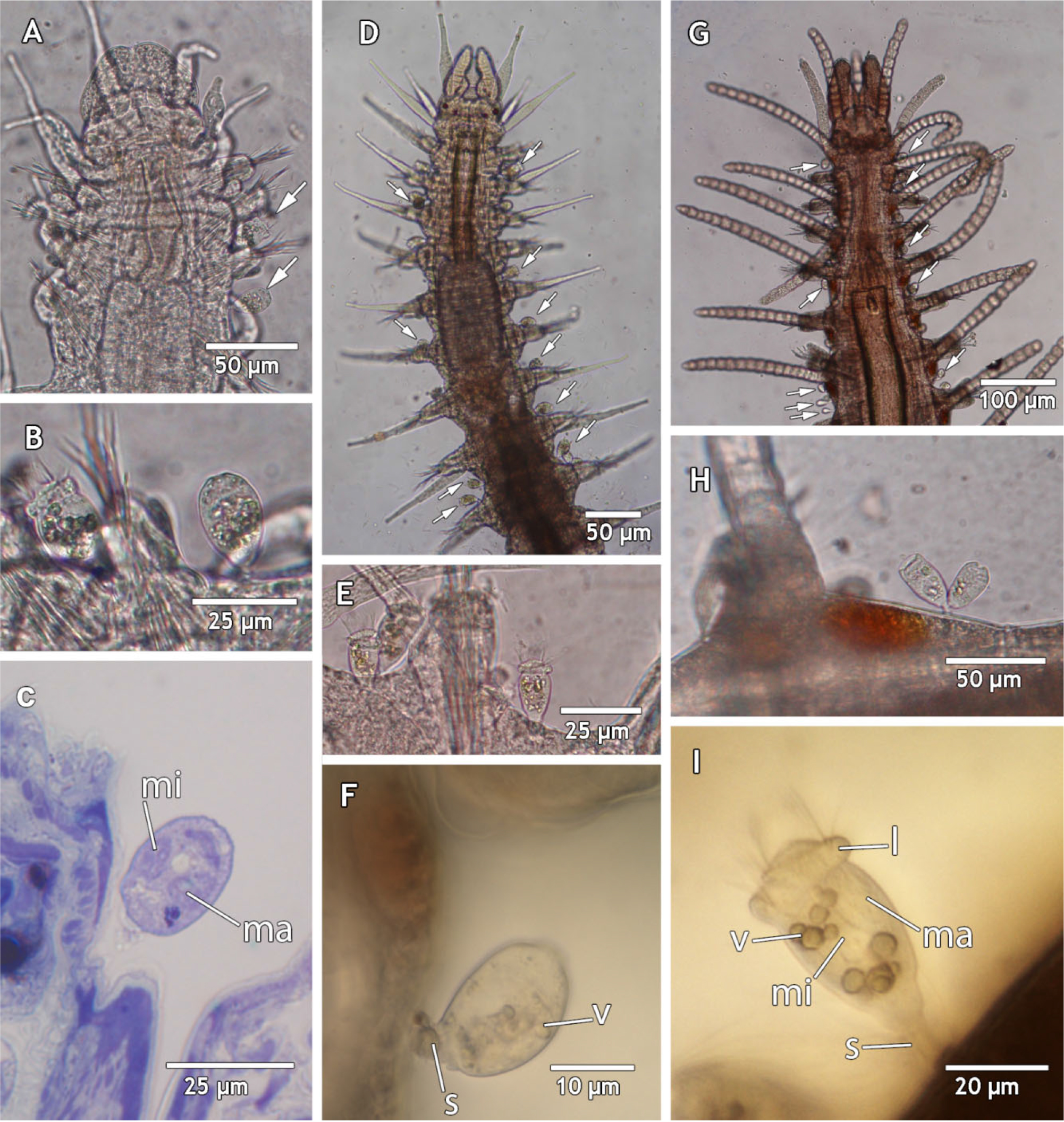

Light microscopy images of ciliate protozoans on different syllid species. Image from Alvarez-Campos et al. (2014).

The symbiotic little cups were peritrich ciliates, a group of protozoans with the shape of a disc or bell, and hair-like appendages. Peritrich ciliates often live as epibionts (symbionts that attach to the external surface of the host) of different marine organisms, but no one had observed them as epibionts of syllid polychaetes yet! And even more exciting, the three different species of little cups we found turned out to be new species to science. We teamed up with an expert on the taxonomy of this group of organisms and described the three new species of protozoans.

So not only did we discovered a new symbiotic association between polychaete worms and protozoans but we also discovered and described three new species to science. And all of this happened while we were studying the diversity and reproductive patterns of a few species… and it happened because of scientific curiosity.

As Einstein said:

“The important thing is not to stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existence. One cannot help but be in awe when he contemplates the mysteries of eternity, of life, of the marvelous structure of reality. It is enough if one tries merely to comprehend a little of this mystery each day.”

You can read the scientific article we wrote reporting this discovery here.

0 Comments