If you’ve ever kept a reef aquarium, then you’re probably already familiar with the soft corals that are classified within the Order Zoantharia. Included here are the ubiquitous “Zoas” and “Palys” that fill many an aquarium, as well as the equally common “Yellow Polyps” (which remarkably still awaits a formal scientific description in Terrazaonthus). Then there are some more rarely seen groups, such as the “Snake Polyps” of the genus Isaurus… the white Epizoanthus associated with the Spider Sponge… the faux-sun coral Parazoanthus axinellae… the Acrozoanthus “Stick Polyps”… and several other odds and ends that occasionally show up. What all these species have in common is that they are colonial organisms that expand through asexual budding; however, a newly described species from Japan shows that such isn’t always the case.

The genus Sphenopus is surely one of the least-known groups of shallow-water coral, despite possessing some very unique morphological and ecological specializations. Unlike their multi-polyped (polypolyped?) brethren, the corals in this genus can grow to a massive size (with polyps reaching up to four inches tall!) and lead a solitary existence in sandy habitats They make a living capturing prey, as none of the known species appear to possess the symbiotic zooxanthellae that are common to most reef-dwelling taxa. In many ways, these are the most anemone-like of the zoantharians.

Though they have been known to science since the 18th century, little work has ever been done on this genus. Only one species, Sphenopus marsupialis, has been regularly encountered in the wild, as it occurs throughout the tropical waters of the Indo-Pacific in depths of around 10-25 meters. Owing to the sediment grains that these corals accumulate within their bodies, they have traditionally been classified together with Palythoa as the Family Sphenopidae; however, recent molecular study has now strongly indicated that they actually derive from within that genus, meaning the unusual qualities of Sphenopus originated from what was originally a fairly typical “Paly” ancestor.

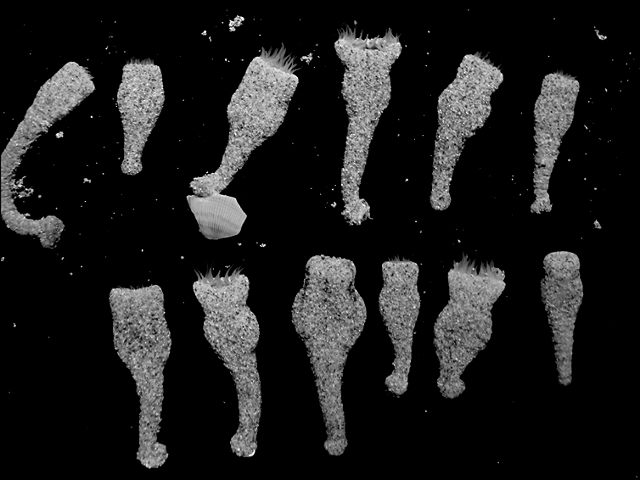

The highly modified body of Sphenopus marsupialis. Credit: Reimer et al 2014

Aside from S. marsupialis, only three other species have been described. A questionable species, S. arenaceus, with no known distinguishing traits aside from its reddish hue was once collected from the Torres Strait north of Queensland over a century ago. The equally rare S. pedunculatus has been seen less than a handful of times since being described in 1888 and is known only from the Coral Triangle. The scientific name alludes to the elongated attachment (i.e. the peduncle) found only in this species, which it uses to adhere to rocks.

Sphenopus exilis seen in situ in a black and white photograph. Modified from Fujii & Reimer 2016

The most recently discovered member, which is described in the latest edition of Zookeys, is Sphenopus exilis. It was found in the shallow, sandy bays of Okinawa, Japan, buried up to its oral disc in sediment. The main distinguishing feature of this new coral is its small size relative to the massive S. marsupialis, as the largest known specimen measured in at just 11mm across and 24mm in length (roughly the size of a Yellow Polyp). It is also more elongated, though never quite so much as in S. pedunculatus and never does it attach to hard substrates as that species is capable of.

Sadly, Sphenopus are seemingly never available in the aquarium trade, though this is likely due to a perceived lack of demand rather than any difficulty finding and collecting these corals. In the right habitat, these are no doubt quite abundant and, as they are capable of reaching several inches in size, are surely prominent and impressive creatures in the wild. Maybe if these came in fluorescent rainbow colors, we would see Sphenopus being fragged and swapped around, but, alas, these reclusive zoantharians are destined to be ignored and overlooked in favor of more aesthetically pleasing species. Sphenopus is one of the ultimate “book corals” out there, though it’s one likely only to be appreciated by the nerdiest of coral nerds.

0 Comments