Throughout the years that I’ve kept marine aquariums, photography has been the driving force fueling my passion. In fact, one of the main reasons I decided to set up a saltwater tank in the first place was to photograph corals with my (then) newly acquired macro lens. One of the first corals that landed in my nano reef, lit by a DIY LED fixture, was a multi-polyp fragment of a Zoanthid species that I received from a fellow reefer. From the moment that the first polyp opened and I could see it in its full glory, I was awestruck- the utterly beautiful red hue of the mouth combined with a glowing green/brown ”skirt” of that coral was like nothing I’d seen before. Shortly after, I grabbed my camera, macro lens affixed to its front, and began my first aquarium photoshoot. Back then, I had zero experience in photographing corals- I didn’t know how to position the camera, how to light the subject, what setting to use when taking pictures of them, none of that. Bah, I didn’t even own a good tripod back then, so my first shoot was taken handheld, with no flash and using auto settings.

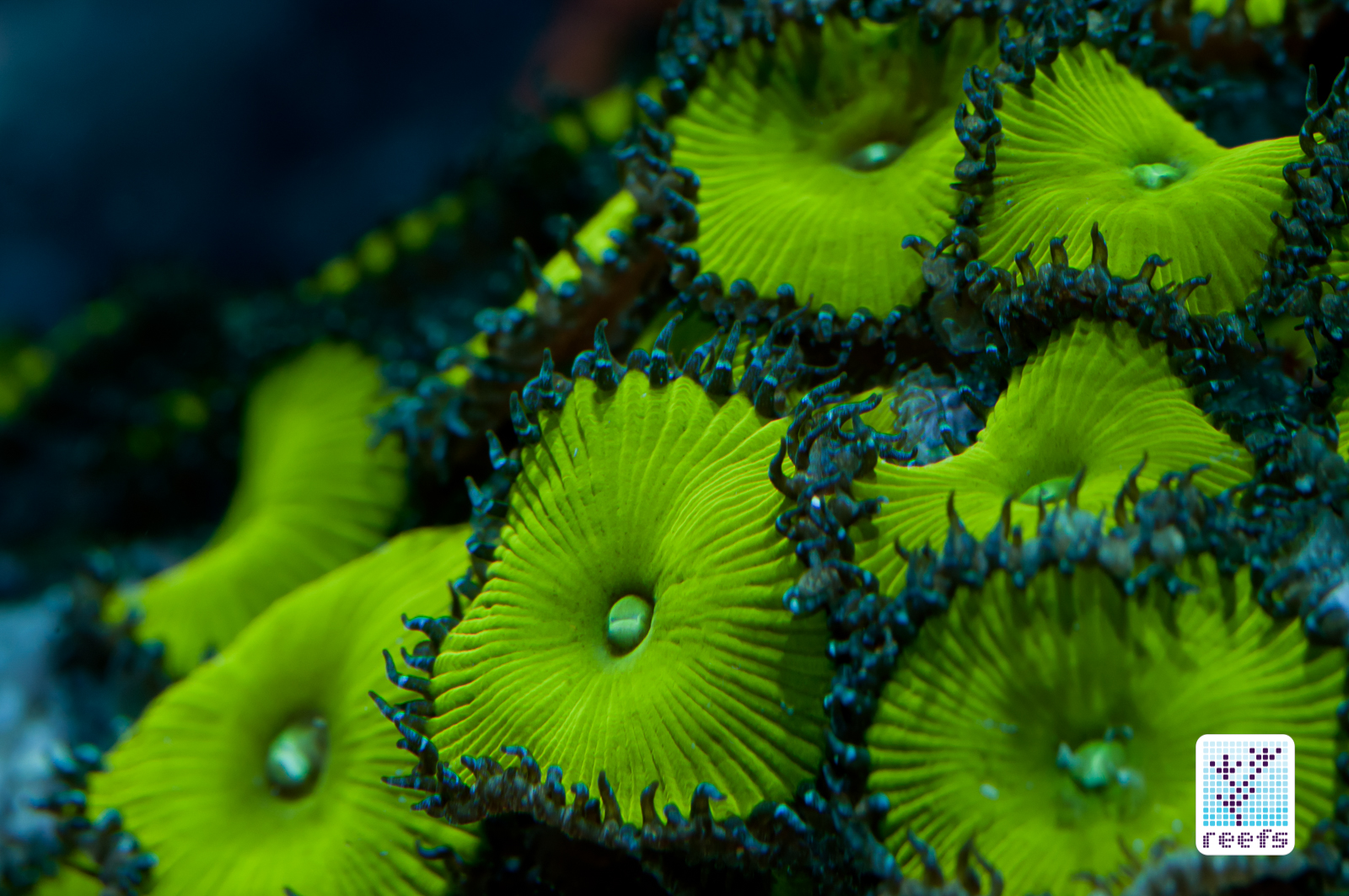

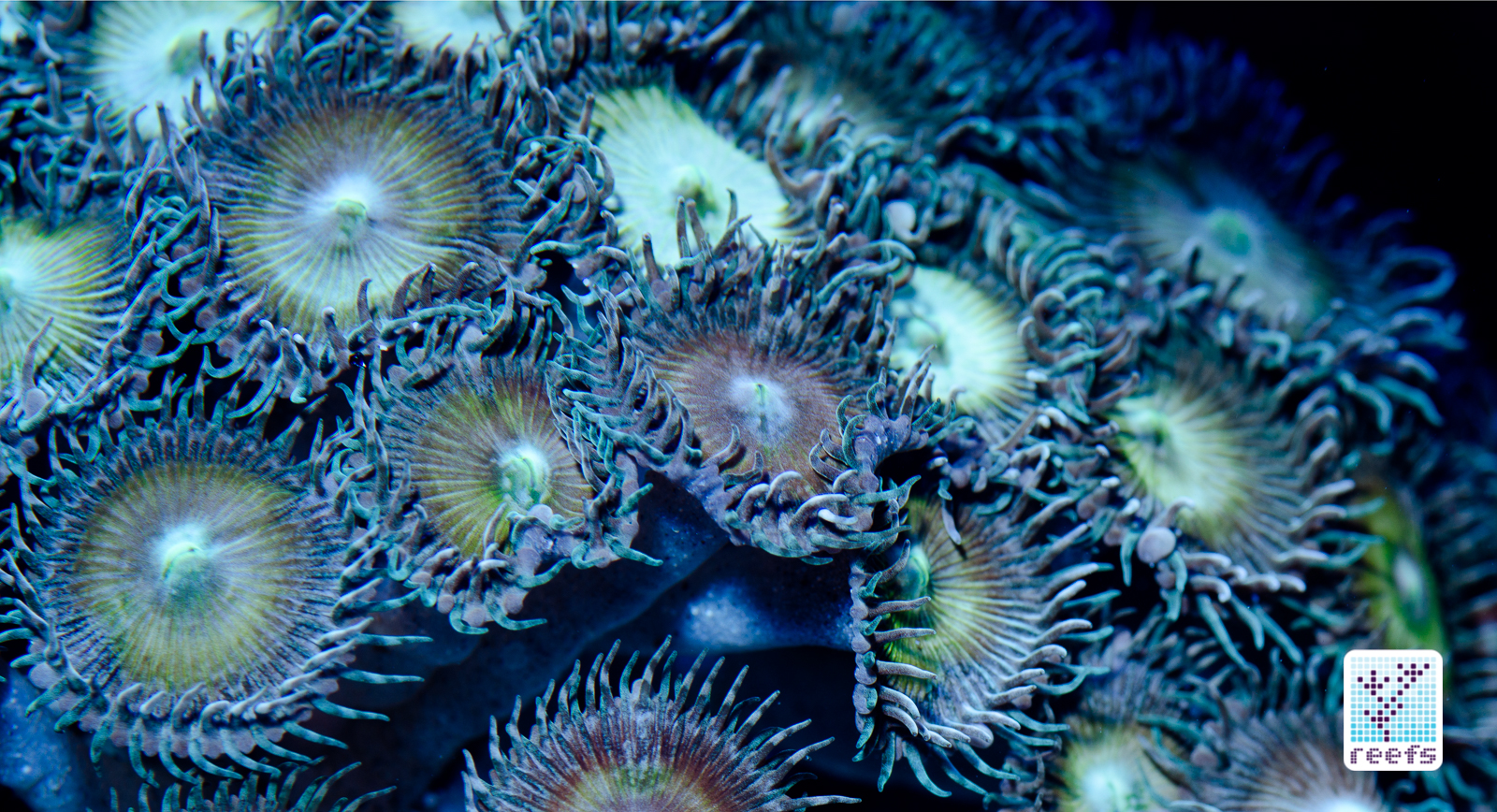

This is what I came up with:

Shot with Nikon D90 and Tamron 90mm f/2.8 macro lens @ f/5.6, 1/80s and ISO 800.

The photograph is dated March 2010

I still own that lens and still love to use it, even that the focus ring is much less reliable that it used to be and despite the fact I now own a Nikon 105mm f/2.8 macro lens that, on paper, is a much better lens. The truth is, I’ve shot with various macro lenses from different manufacturers and from my experience, they are all good in their own regard. A true macro lens, by definition, must be excellent in sharpness and color reproduction, and I’ve found that all the macro lenses I’ve had opportunity to use so far have had those qualities. One may be tad bit sharper than the other and offer a bit more focus accuracy, but in general, any professional macro lens, be it from Canon, Sigma, Nikon, Fujifilm, Tamron, or any other major lens manufacturer, can produce excellent results if the person behind the camera body knows how to use it.

I didn’t at first. Honestly, I still don’t know all the tricks, and when I see pictures taken by well-known coral photographers, I’m still amazed by their talent. I bet they all started like I did, experimenting with different methods, trying to translate their photographic knowledge into the difficult subject of reef aquarium photography. For me, it also entailed countless dollars spent on new equipment and hours of pressing the shutter, hoping that I could capture what was in front of my eyes.

Taking a good, detailed photograph of a coral polyp is harder that it seems, and requires a mixture of experimentation, basic knowledge, and good old perserverence when output photos are not turning out as you want them to.

Anyway, I’d like to steer away from getting too technical in this article, as my initial intent was to share my passion of keeping and photographing zoanthids in the reef aquarium rather than to explain how I came up with pictures that accompany this post. If you are interested in reading more about how I learned to take photographs in the aquarium environment, check out the 5-part series of articles I wrote on the subject, titled “Aquarium Photography Guide” (part V contains links to all others in the series).

Zoanthids? Palythoa? What are they?

Zoanthid species belong to the order Zoantharia, phyllum Cnidaria, which contains more than 10,000 species of animals occupying all aquatic environments (both marine and freshwater) on Earth. Zoanthids are not true corals, in fact they have more in common with anemones and jellyfish species than with the reef building animals they usually share space with. Zoanthids are a common sight in tropical coral reefs throughout the world, but there are also deepwater and temperate ocean dwelling species. Seeing the kaleidoscope of colors that one finds with zoas in the hobby, one would think there are thousands of species of these animals on the planet, but surprisingly, less than 100 species have been described, and recent DNA tests proved some of the previously described species share an identical genome, lowering that number even further. An interesting fact I learned while researching this topic (see footing for references) is that there are so-called sibling species (species that are morphologically nearly identical but are incapable of producing fertile hybrids) occurring in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. That observation supports the idea that there was a common ancestor that lived in what was just one body of water before the Central American Seaway closed up, forming the Isthmus of Panama around 2.8 million years ago (as recent studies suggest) and seperating the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

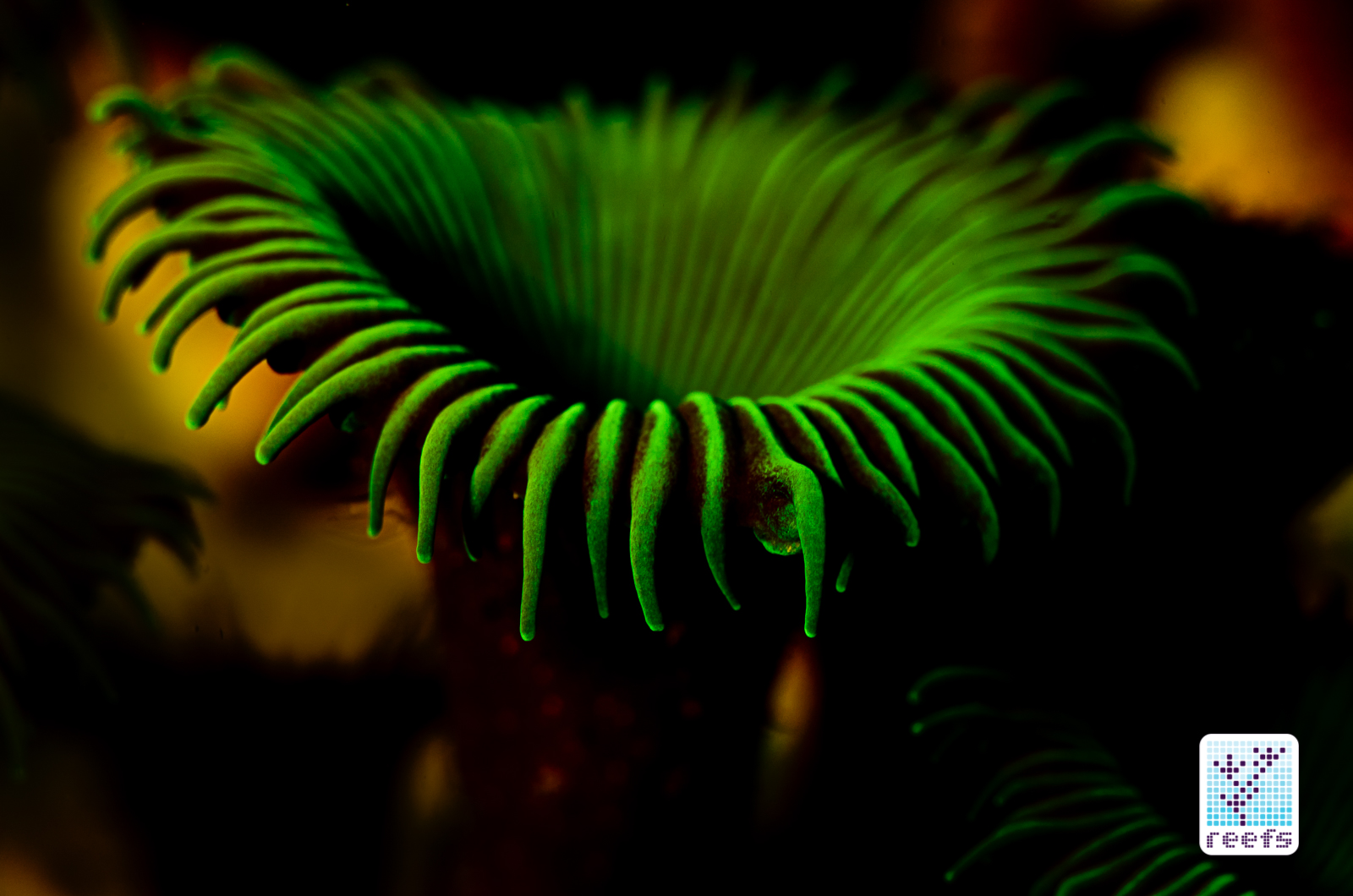

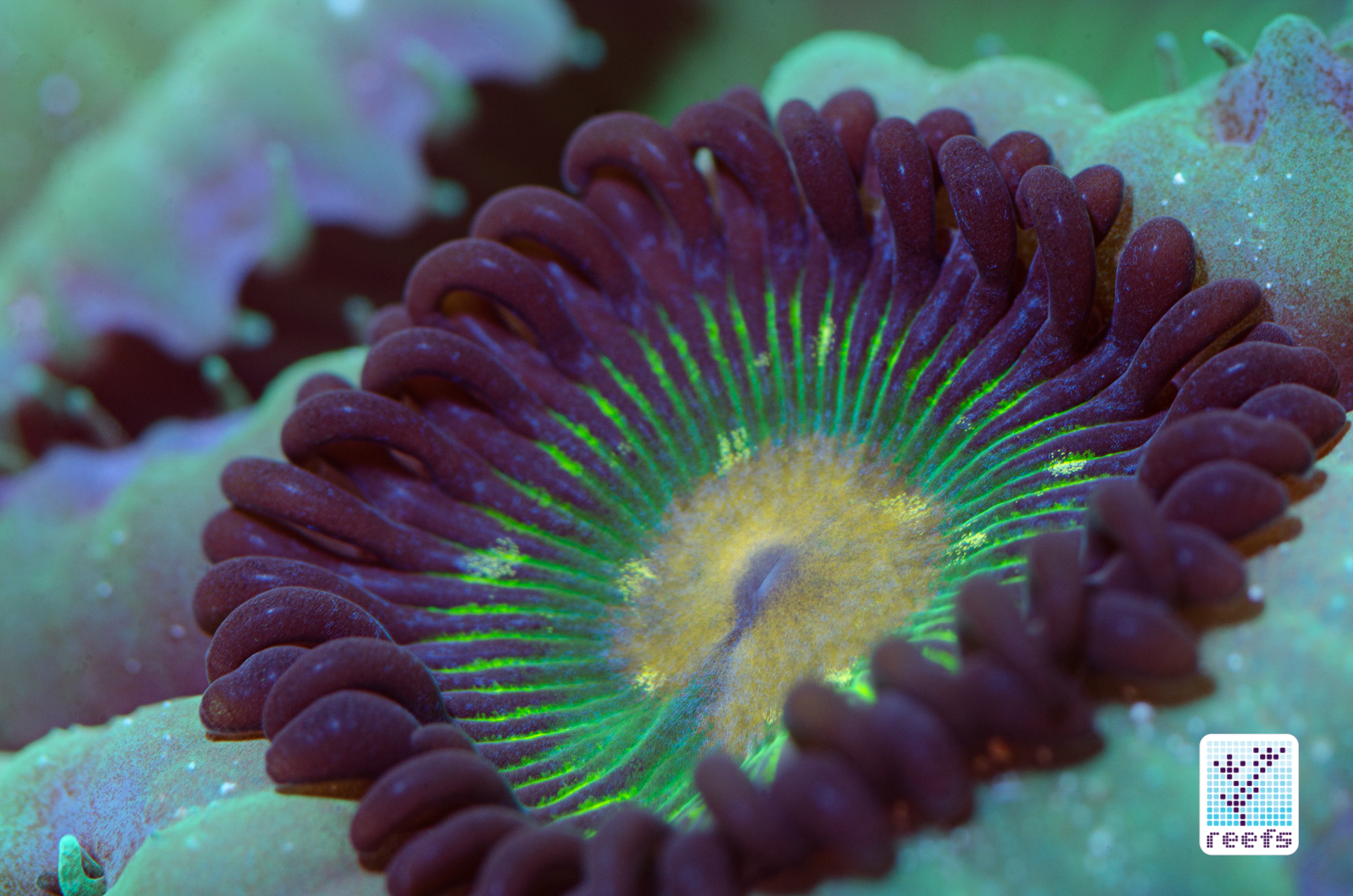

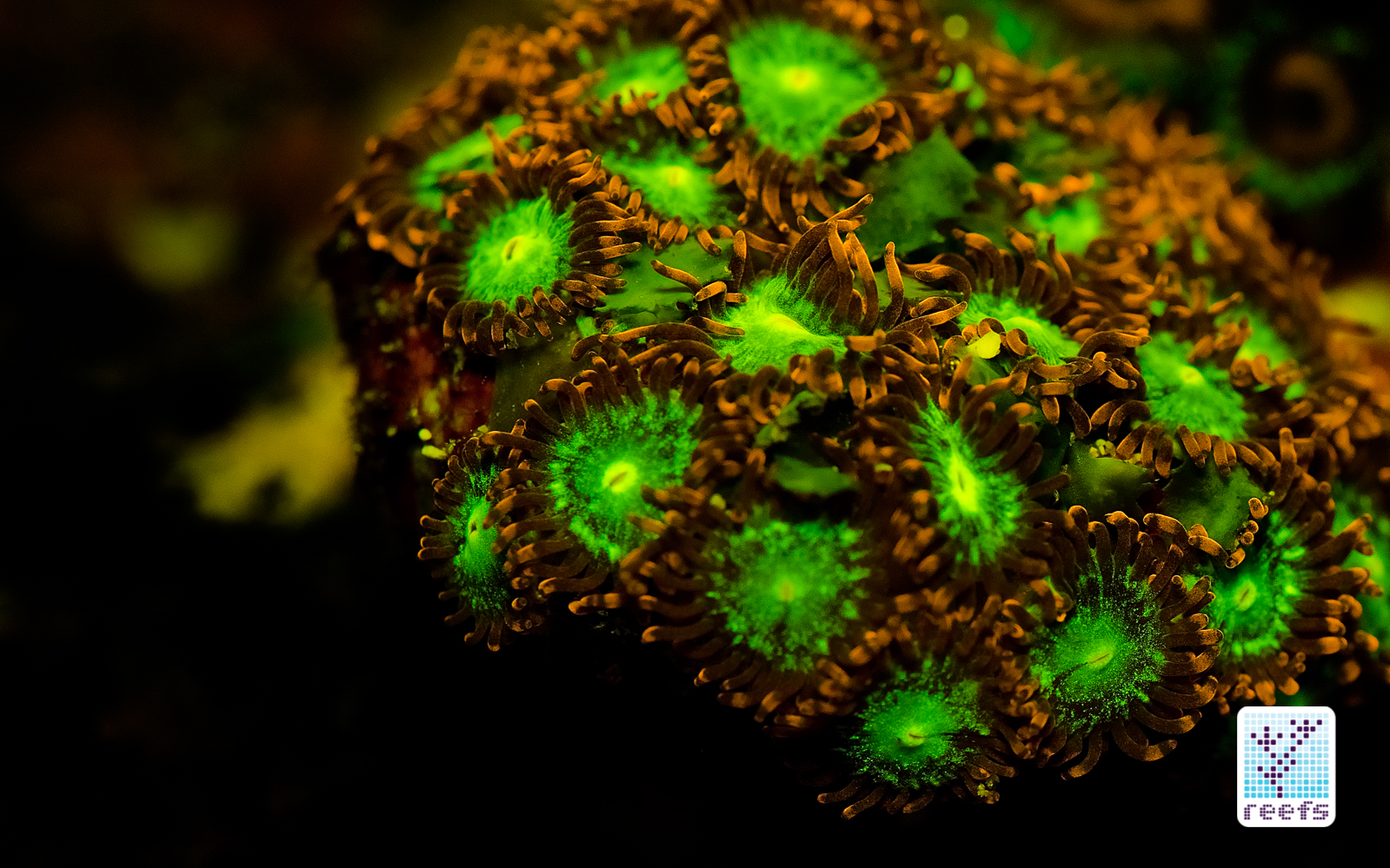

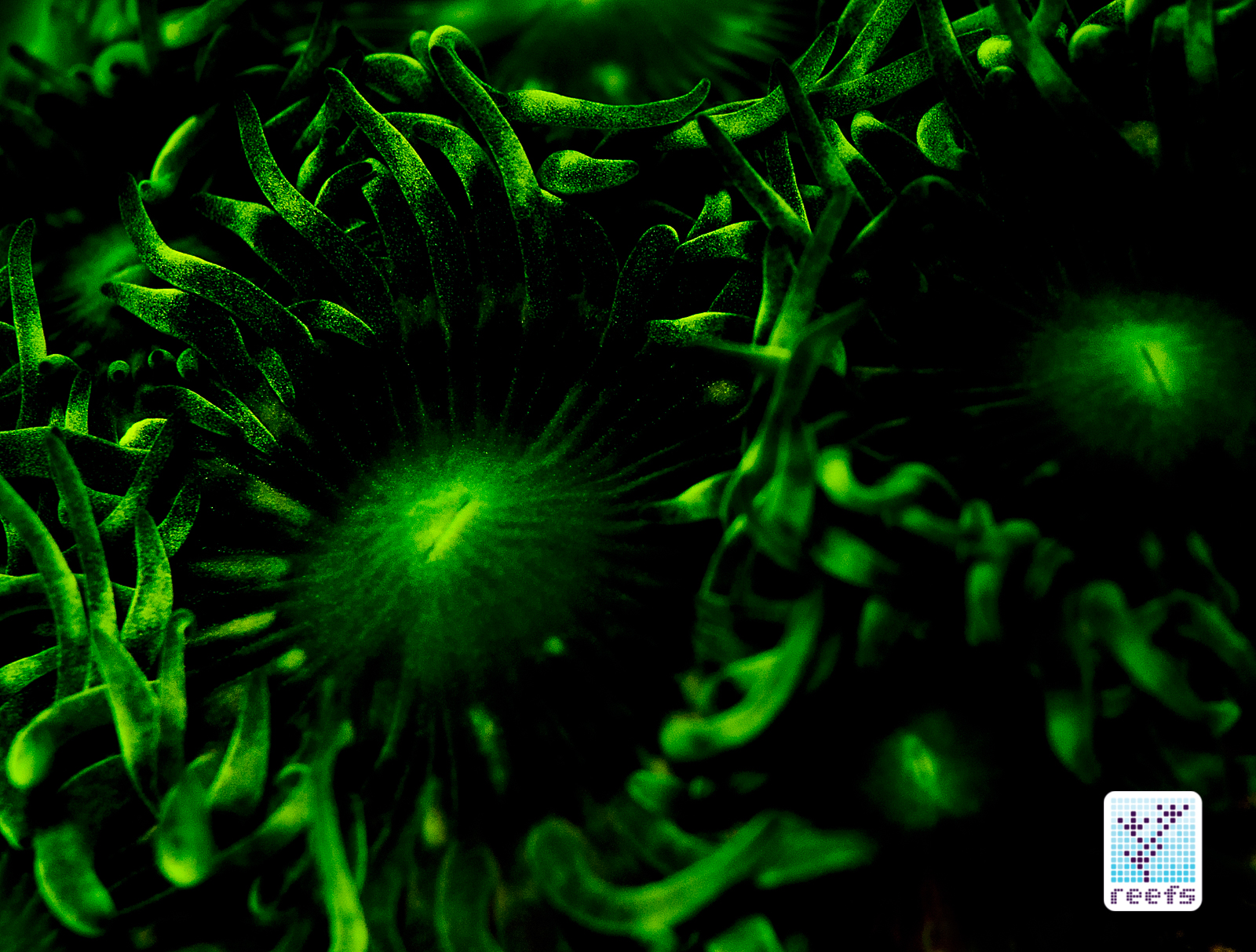

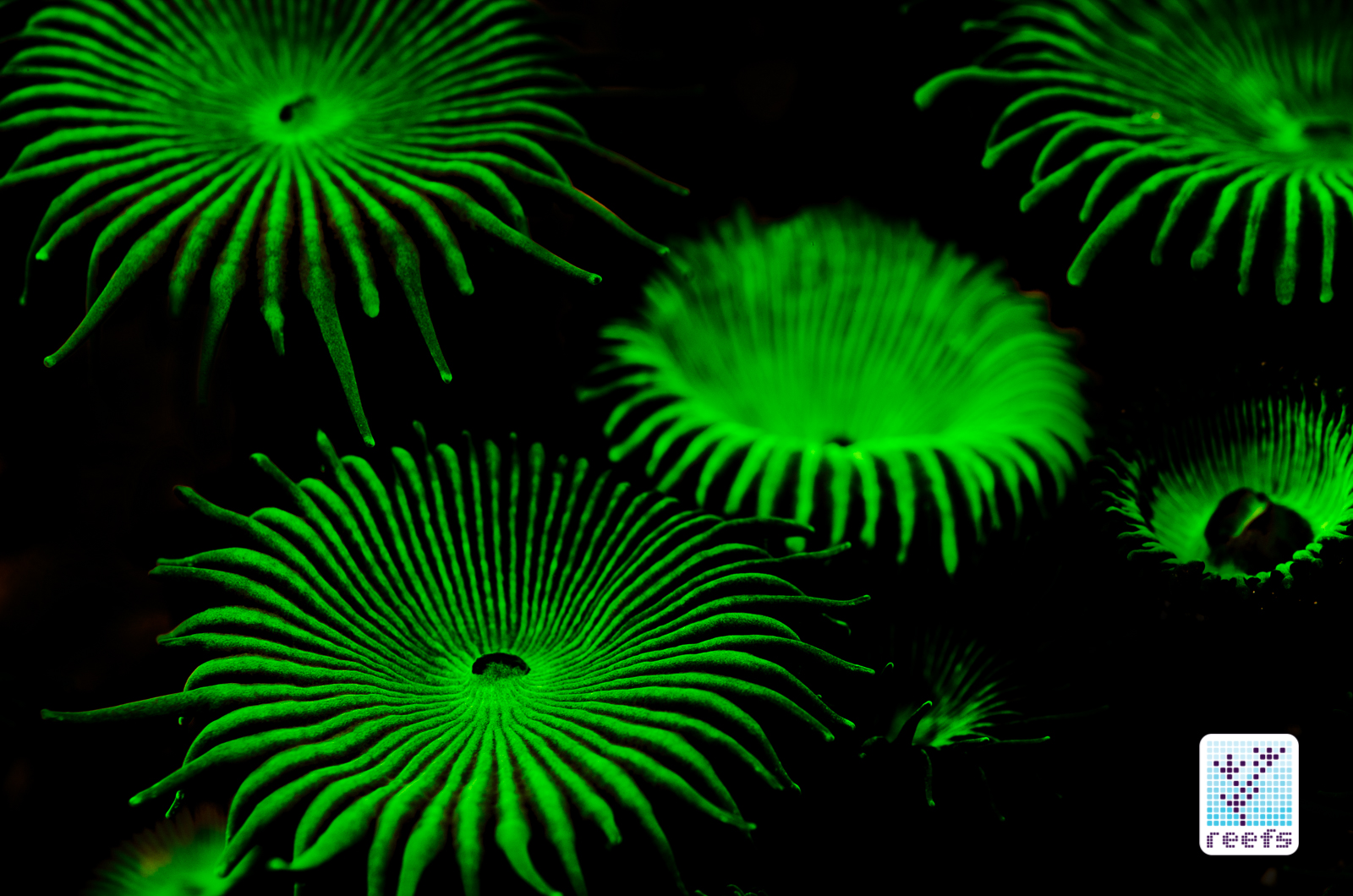

A single polyp of Palythoa species photographed under fluorescence exciting light Nikon D7000 and Tamron 90mm f/2.8 Macro Lens @f/10, 1/160s ISO100

The Palythoa genus that we often confuse as zoanthids looks very similar, but there are some visual clues that separate the two, such as the length of tentacles (Palythoas tend to have longer, more “pointy” tentacles than zoanthids), the absorption of sand grain within the polyp’s flesh (Palythoa species do that while Zoanthids don’t), and the difference in feeding response in aquaria (Palythoa readily accept commercial fish food while Zoanthids do not always react to target feeding). Unfortunately, these physical differences are often not enough information to positively identify individual species. My personal observation, based on keeping scientifically-described species of Palythoa, such as Palythoa grandis, or (common names) Captain America Paly and Nuclear Green Palys, is that Palythoa grow more aggressively than Zoanthids, producing larger, thicker polyps. Regardless, the husbandry and propagation methods in the aquarium environment are almost identical between the two genus described above. I encourage everyone to read more about Zoantharia history, taxonomy, and biology in the reference articles at the bottom of this page.

The first photograph

I have a sort of funny/unfunny story behind one of my first (if not THE first) “proper”, meaning using proper equipment and methodology, photographs of zoanthids I took. It started with an argument on one particular reef forum I was regularly reading at that time. The question was “Do zoanthids benefit from target feeding?” and one of the experienced hobbyists replied simply, “They don’t because they can’t consume any large prey we offer”. While I wasn’t sure (and still am not, to be fair) if target feeding zoas helps them grow faster and larger, I found the above statement untrue and so I replied, “But they most certainly do, mine eat Mysis”. The fact I was still a noobie with minimal post count glued to my profile’s avatar didn’t help my case, so my statement was quickly dismissed and I was mocked by others on the forum (it wasn’t a very friendly place to share opinions). I thought “Challenge accepted!” and started shooting away.

A few days, hundreds of shutter presses, and about 20 cubes of frozen Mysis later, I managed to capture the moment. I must admit, I was really happy to stick it into that guy’s inflated ego! I posted this picture with a single word in the comment- “Here:”) and migrated to another forum, never to be seen again.

Zoanthid polyp eating Mysis shrimp

Details: Nikon D90 with Tamron f/2.8 Macro lens @f/16, 1/200s ISO200, off-camera flash

Details: Nikon D90 with Tamron f/2.8 Macro lens @f/16, 1/200s ISO200, off-camera flash

Shooting zoas (and palys) throughout the years

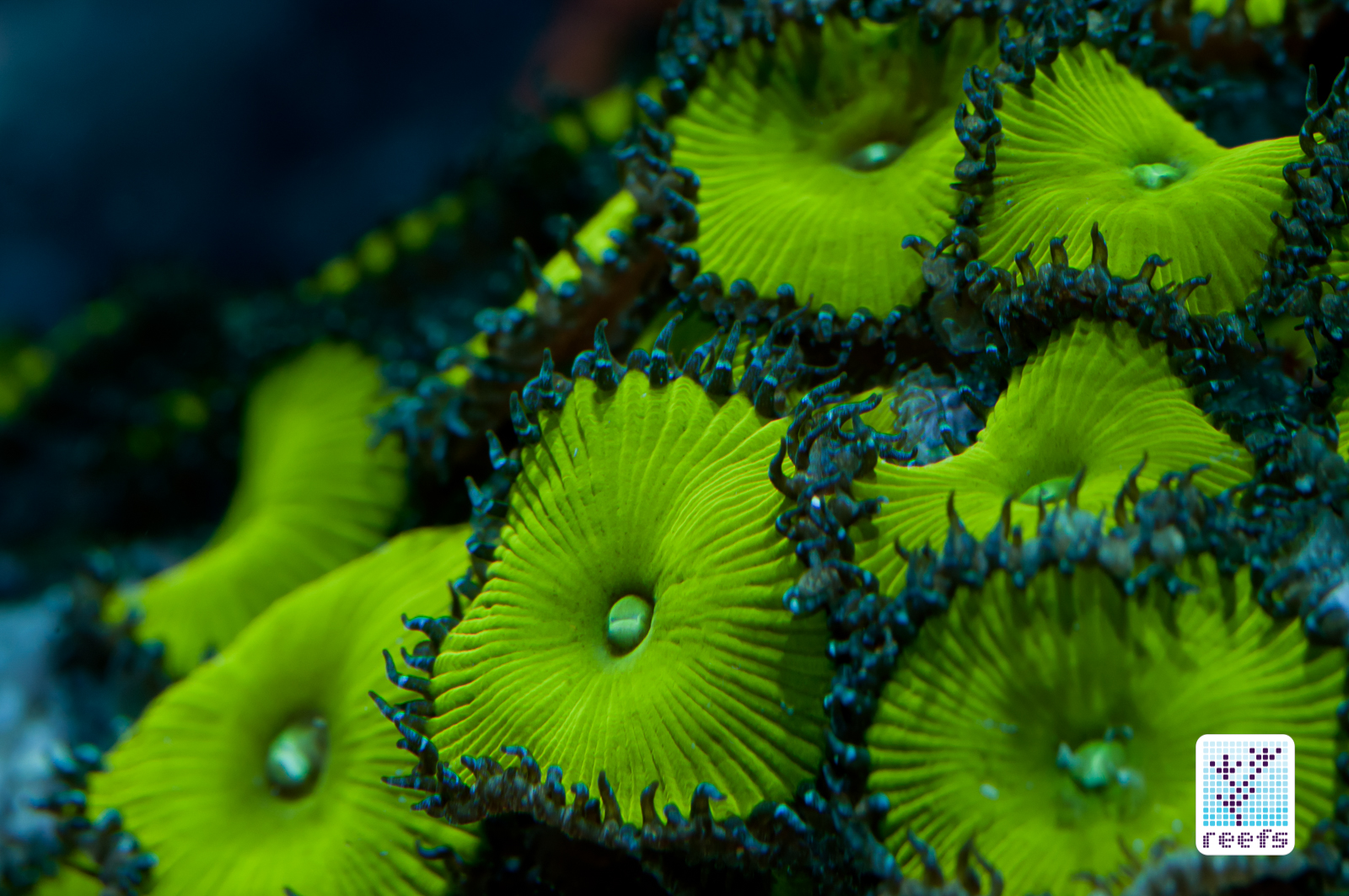

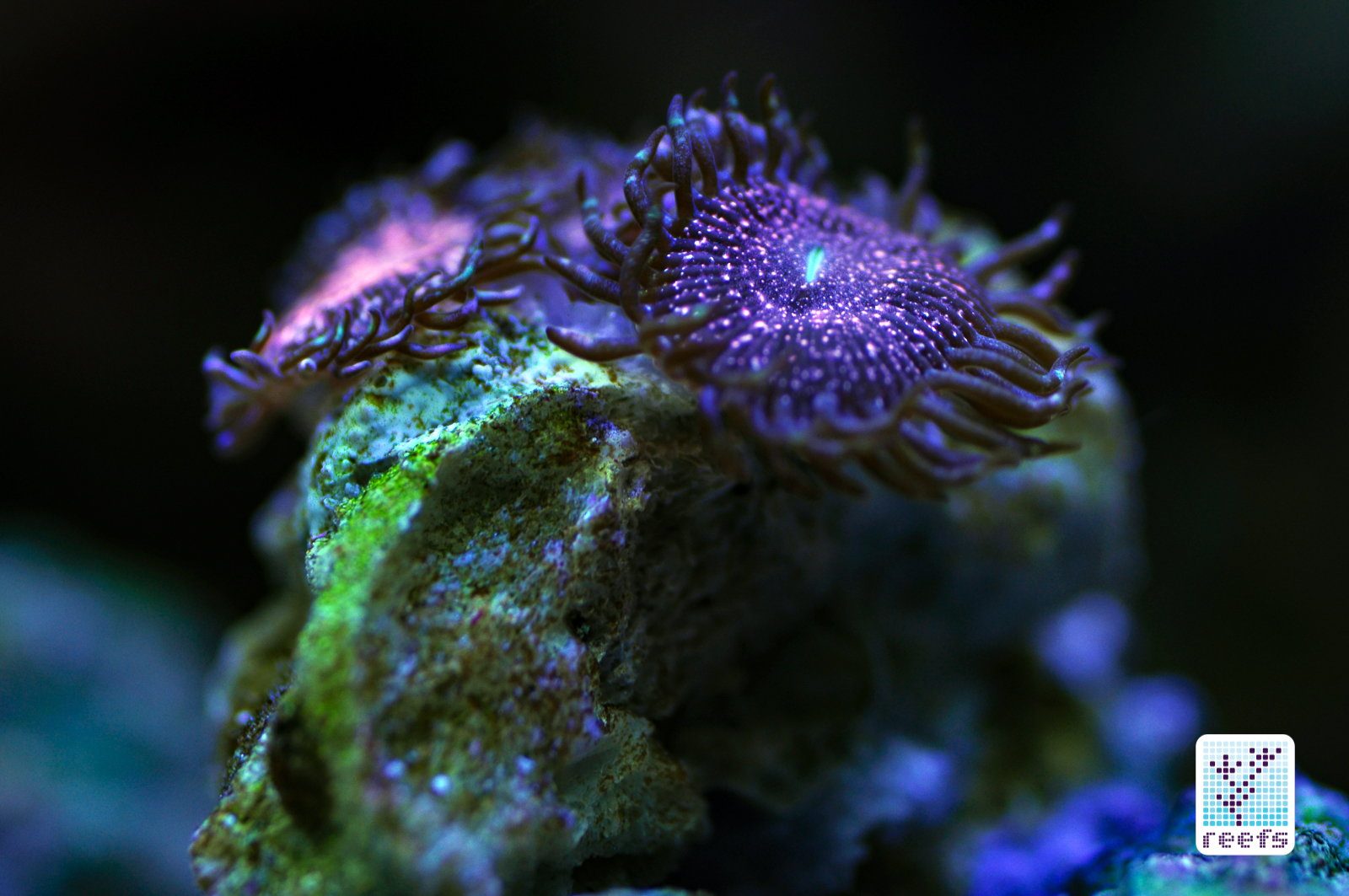

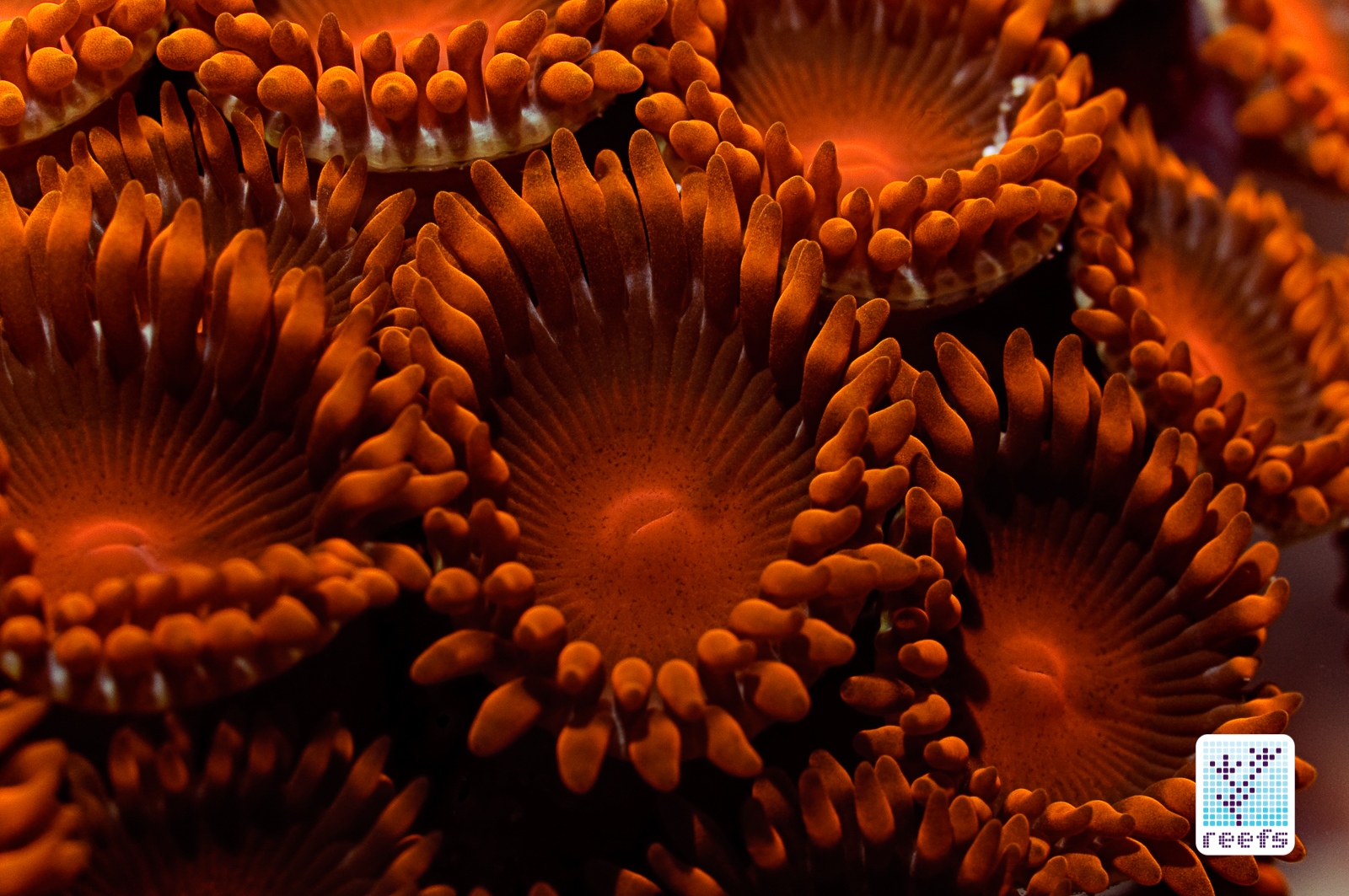

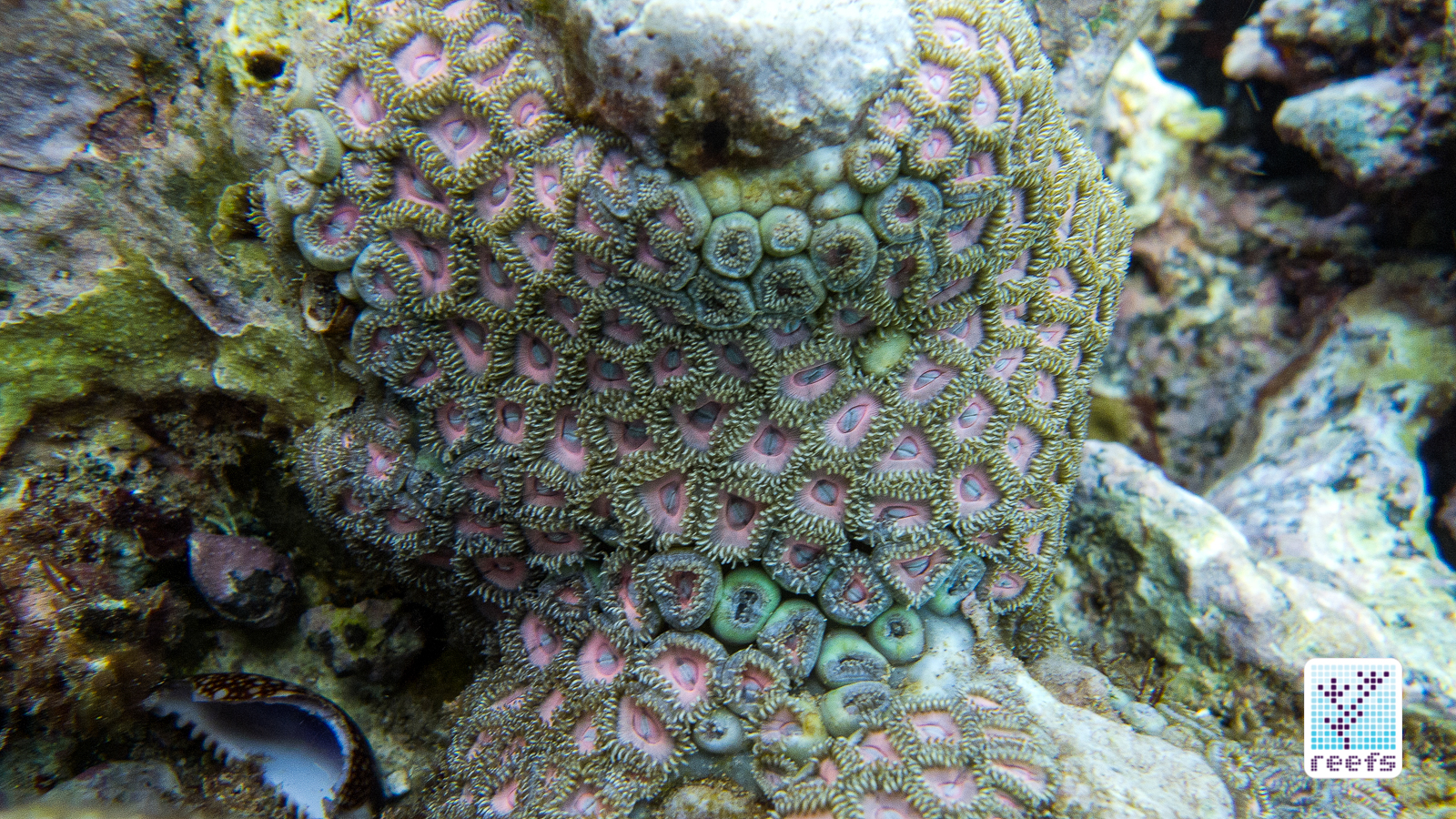

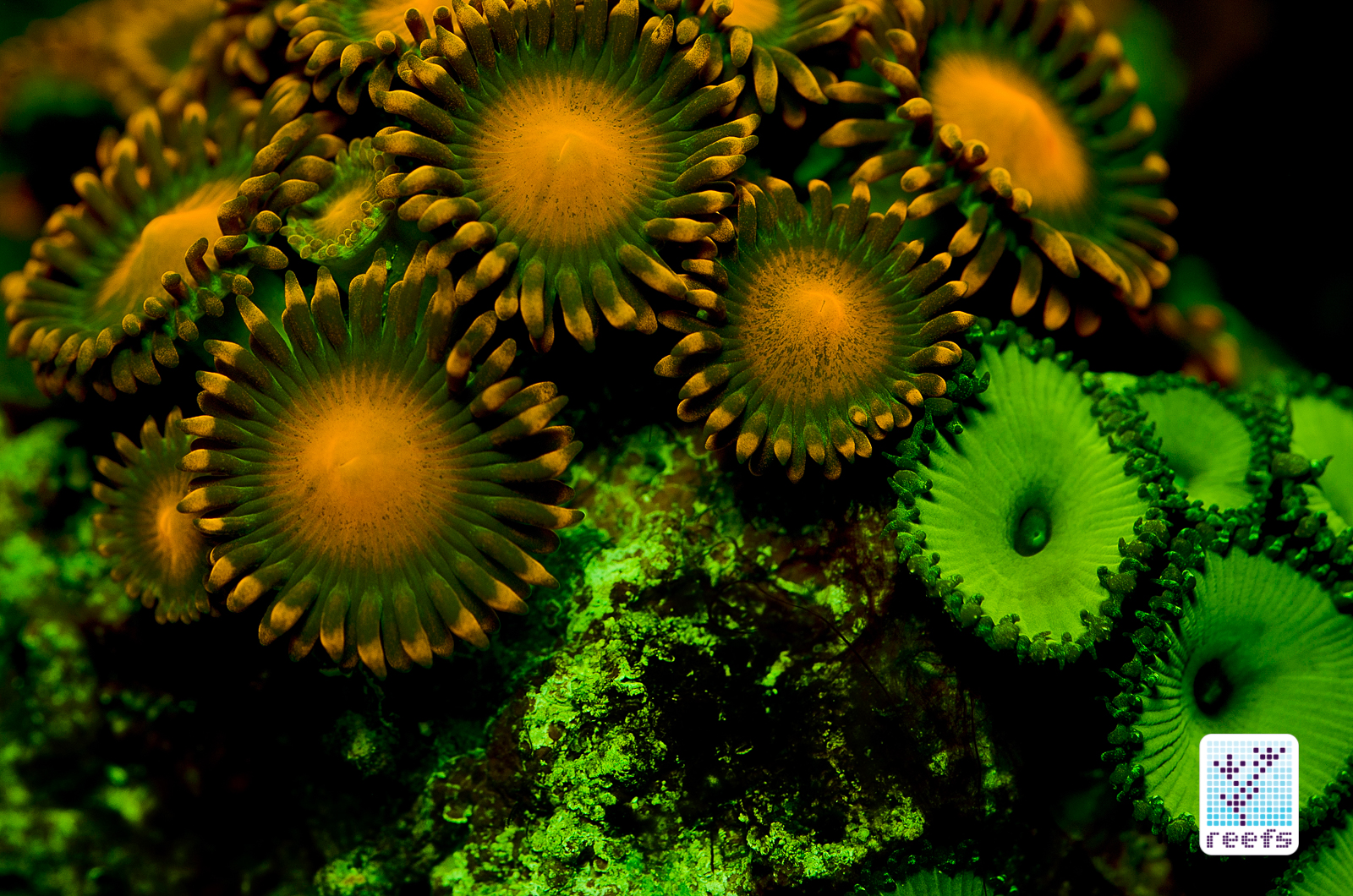

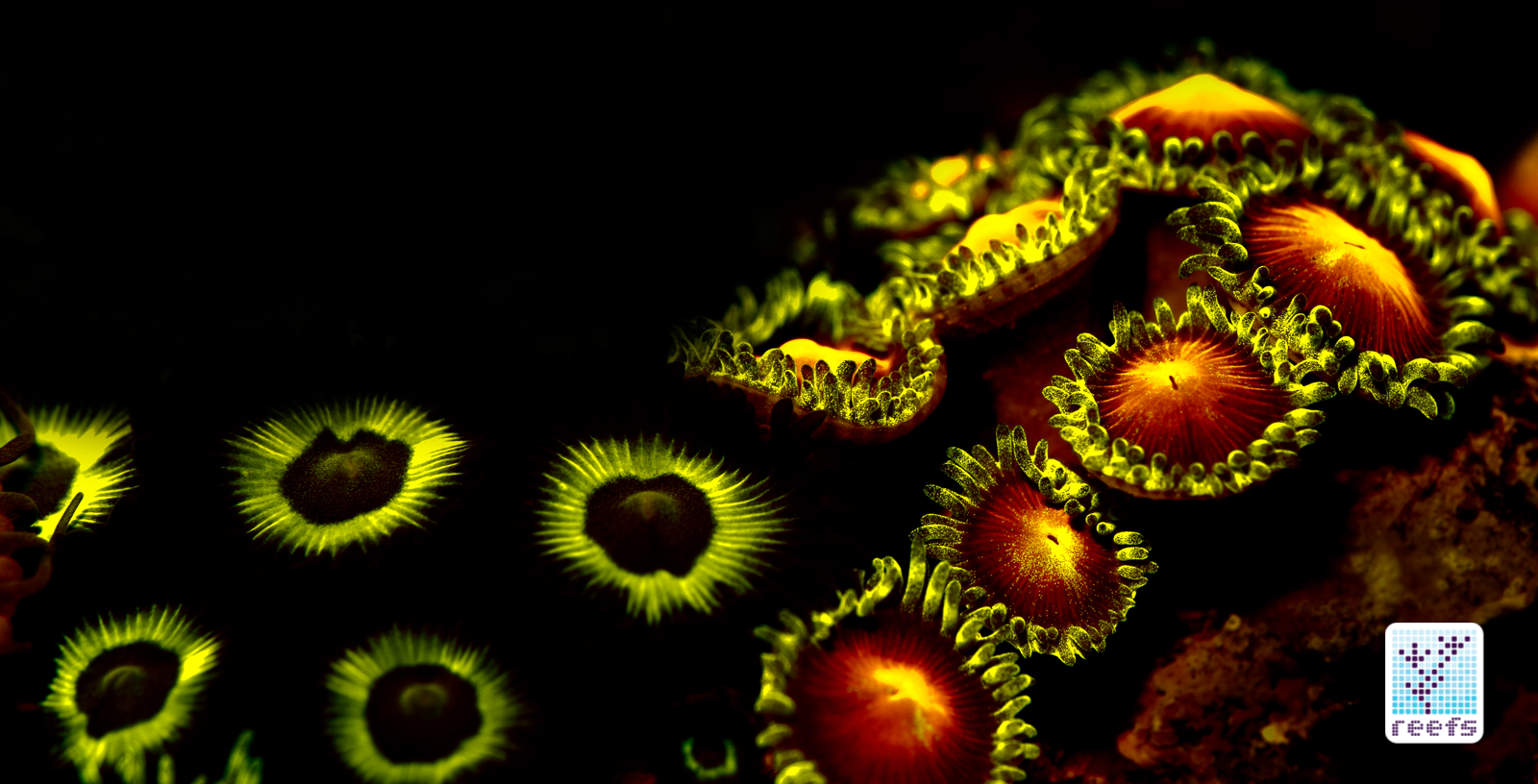

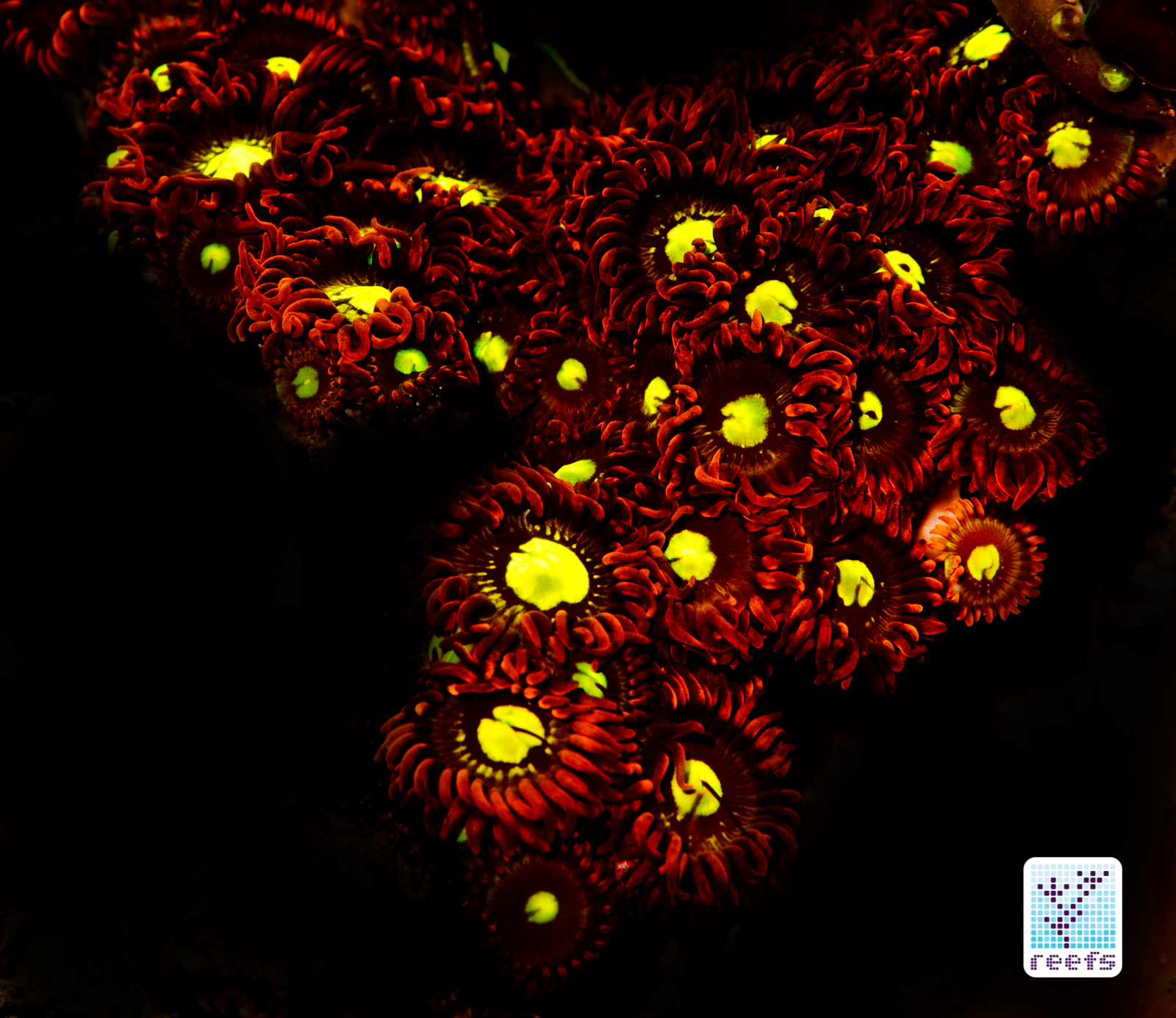

Zoanthids and Palythoa will forever be my favorite subject for reef photography- I still cannot comprehend how something so simple in its biology can be so sophisticated in its appearance. Every time I obtain a new color morph I am amazed by its uniqueness- some polyps, when viewed up close, remind me of formations found in outer space- galaxies, nebulas, supernovas; some resemble pieces of mouth watering candy, while others look like they were taken out of psychedelic art pieces from the late 1960’s.

I never approach my reef photography from a purely documentation perspective- instead, I try to find abstract shapes in the living forms that occupy our home reefs, so that the viewer has to use his/her imagination to decipher the individual forms from the soup of color, shape, and pattern.

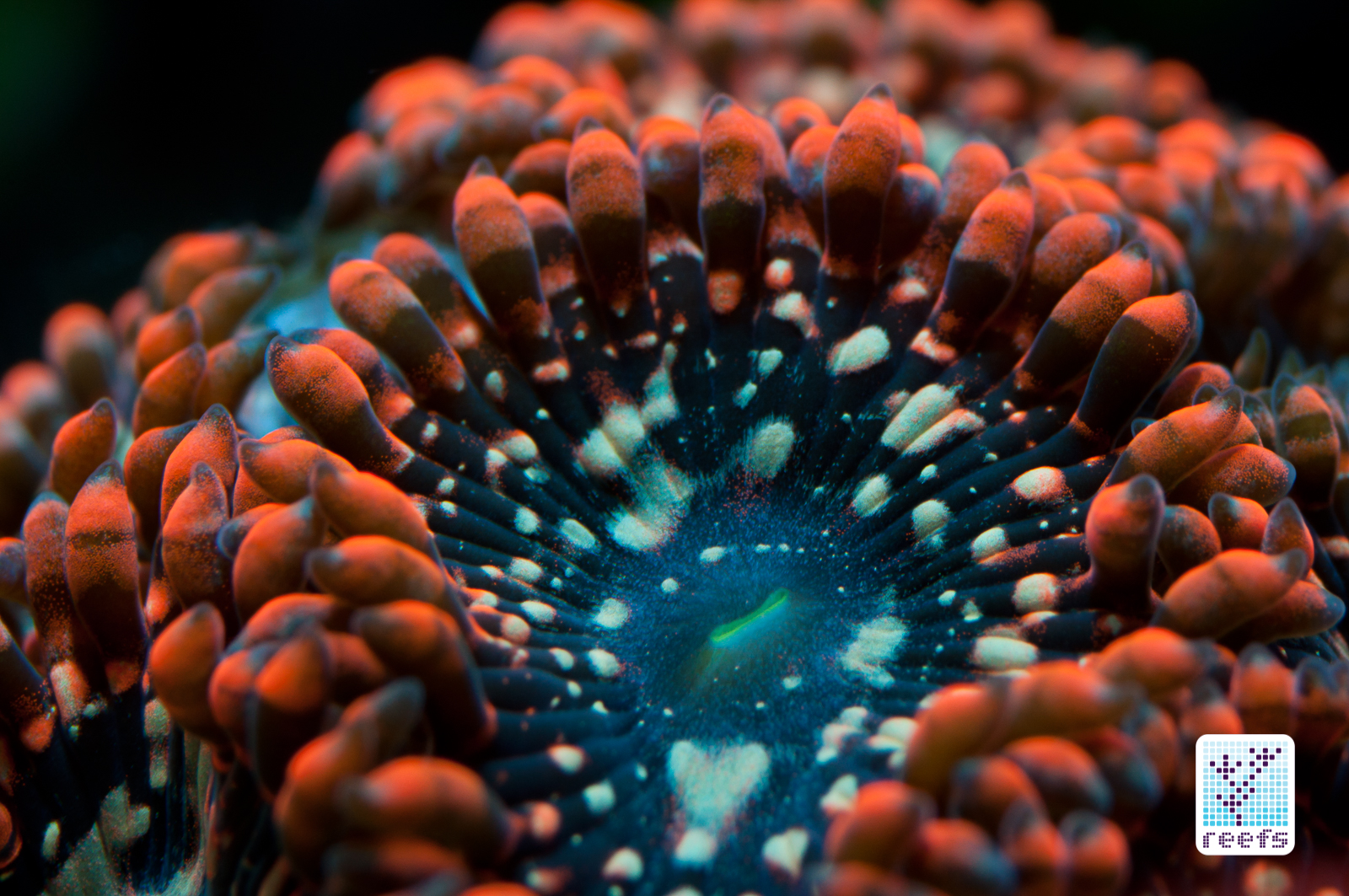

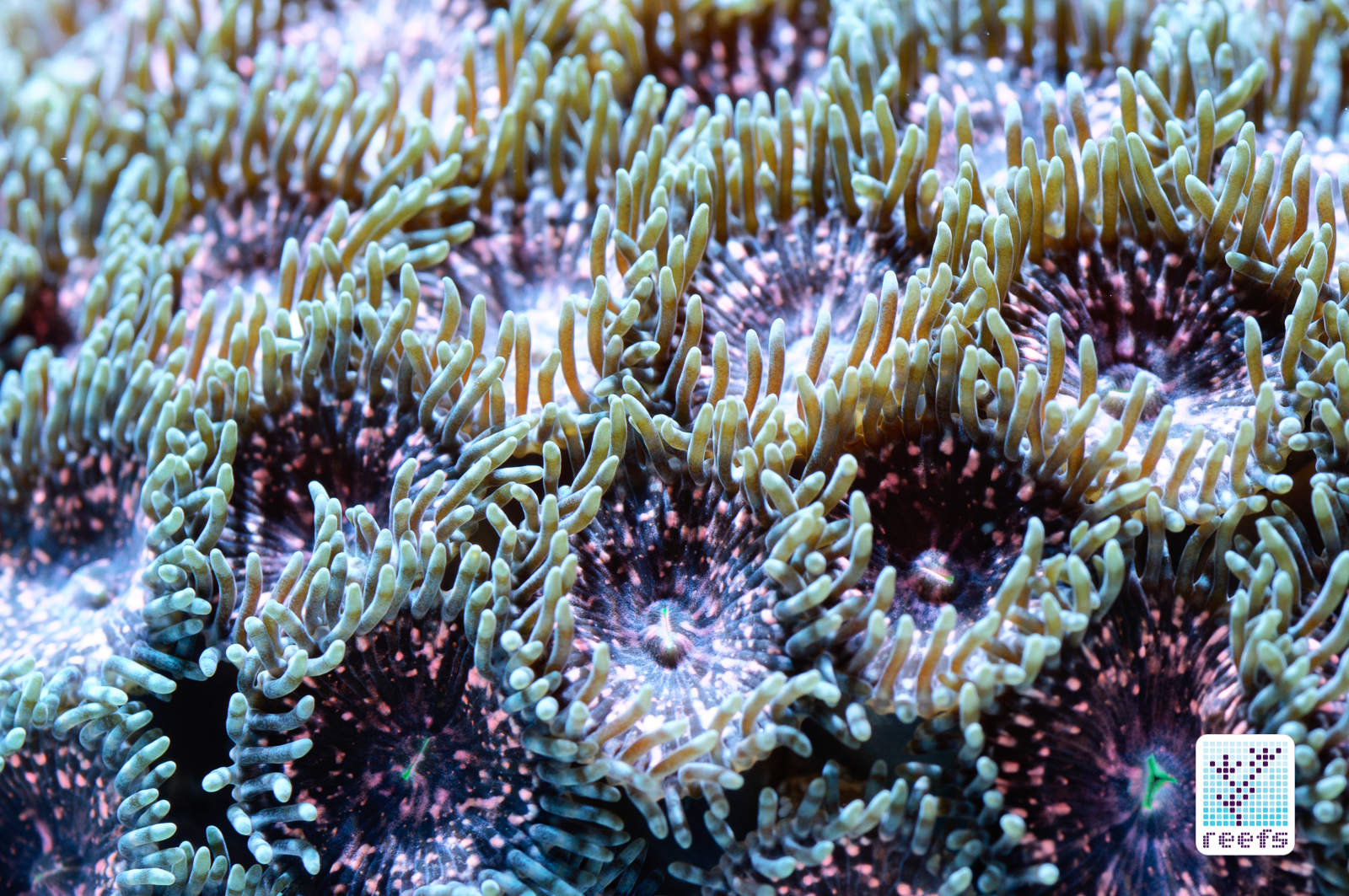

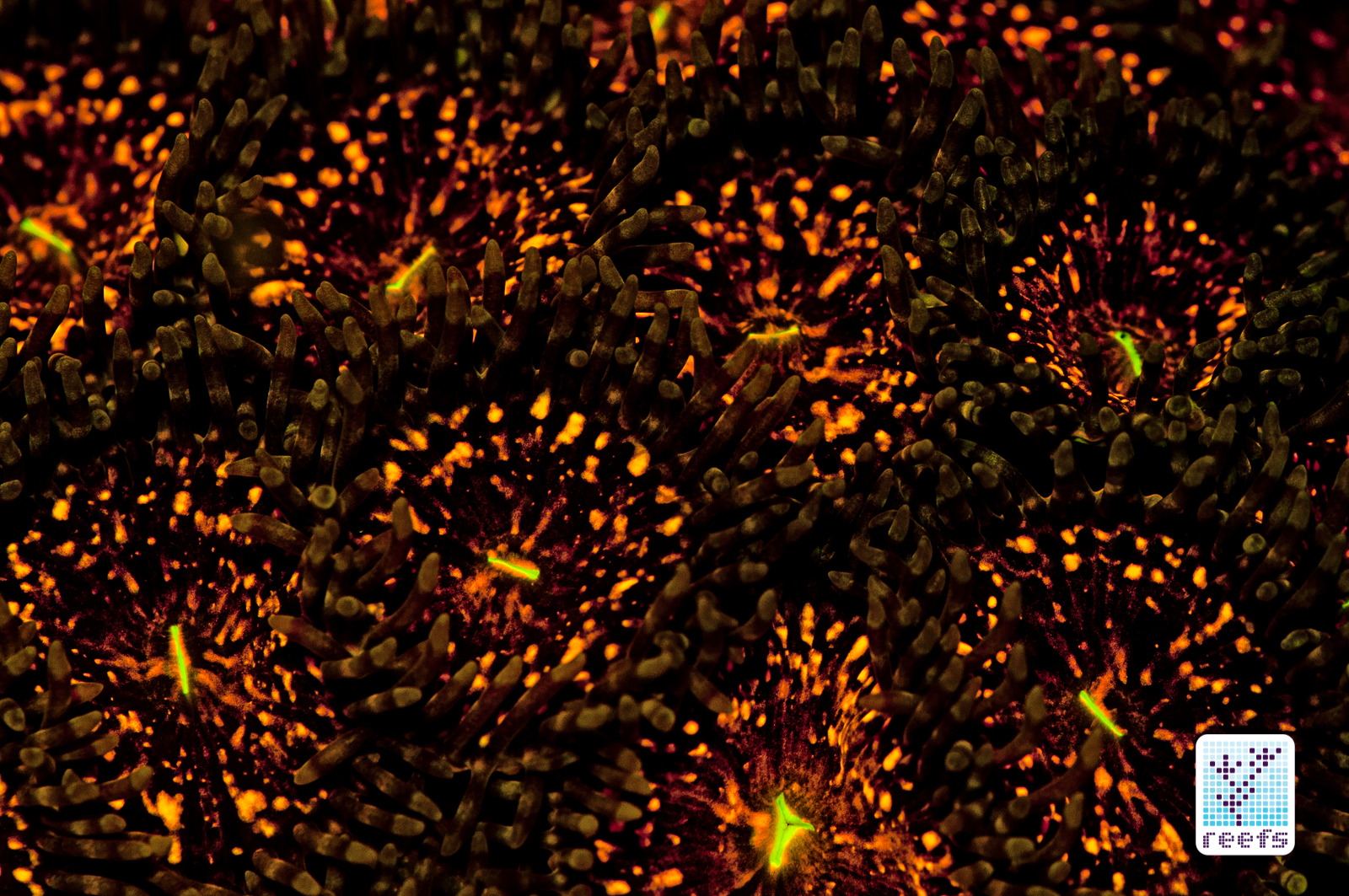

Individual polyps or small group of them, when isolated in extreme macro photography, show the complexity and order of the color pigments in the zooxanthellae algae present in their flesh. Colonies of these single-celled dinoflagellates, without which zoanthids and palythoa could not live, are organized into complex patterns and shapes that amaze aquarists and scientists alike. This order, mastered over millions of years of evolution, is something only the natural world could execute with such beautiful precision.

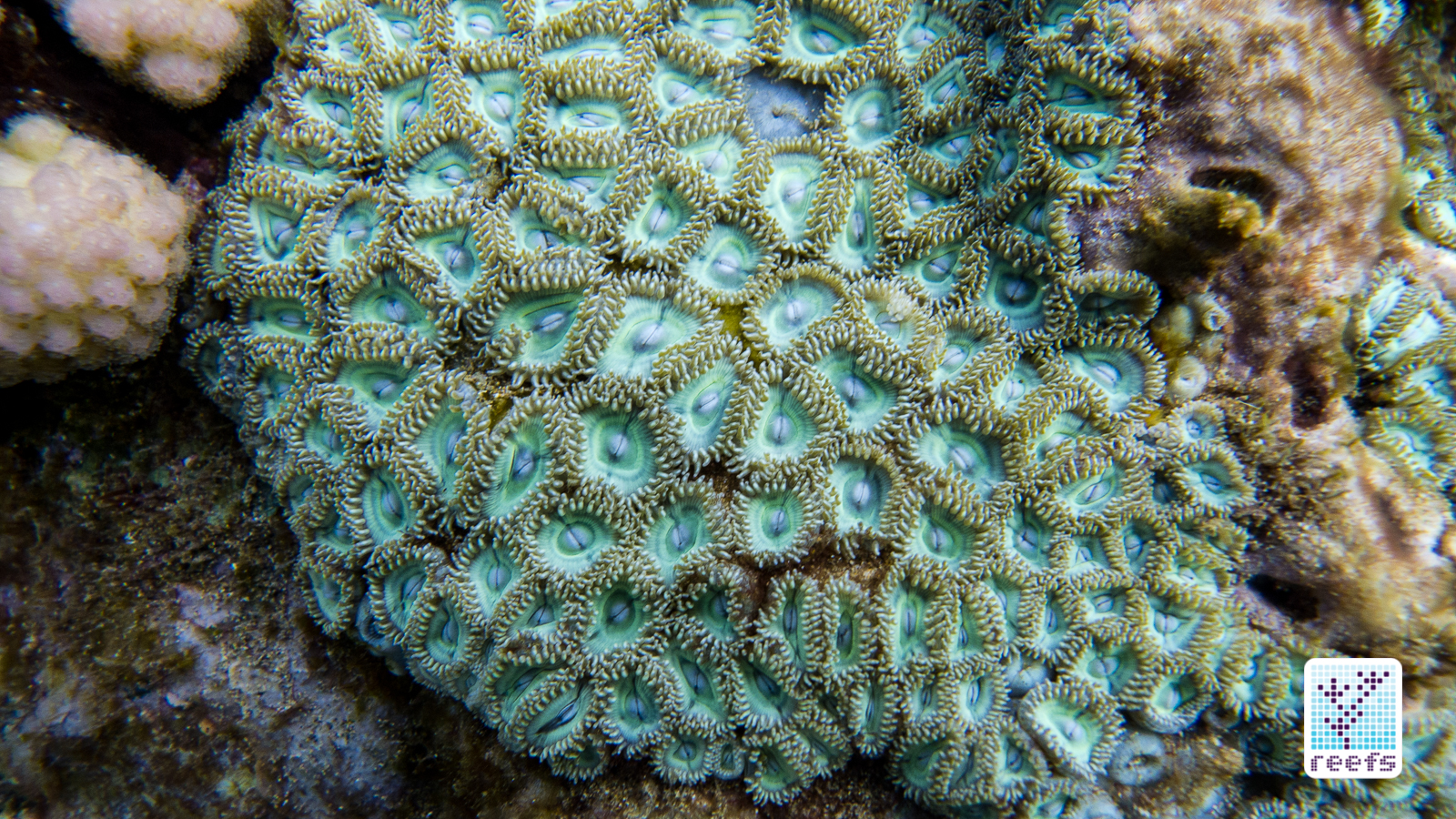

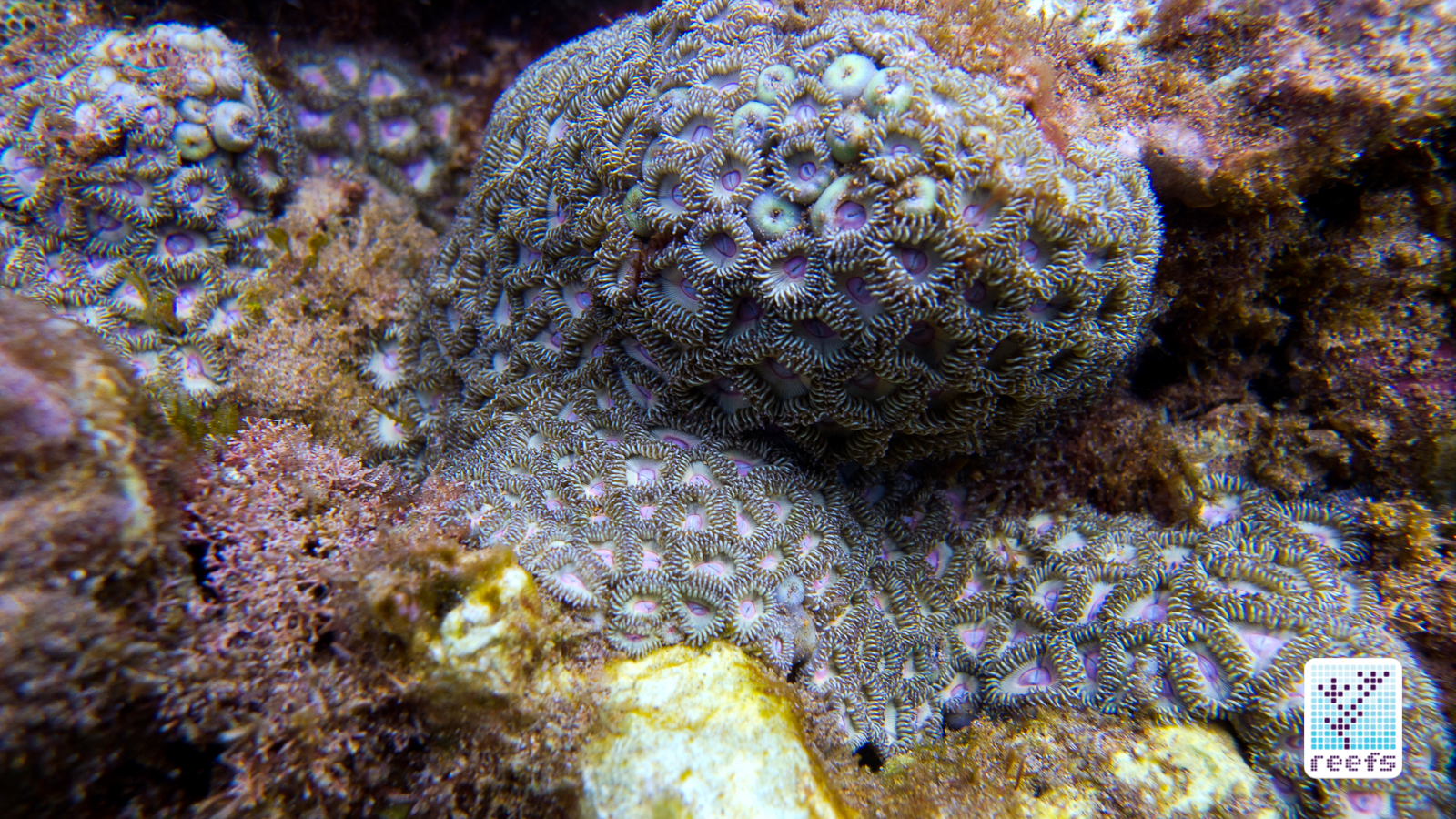

Zoom the field of view out a bit and the singular sophistication of the zoa/paly polyps gives away to a different kind of order, one where a number of individual animals form a uniform, almost mathematical in its nature, arrangement, a sort of grand scheme of color and pattern.

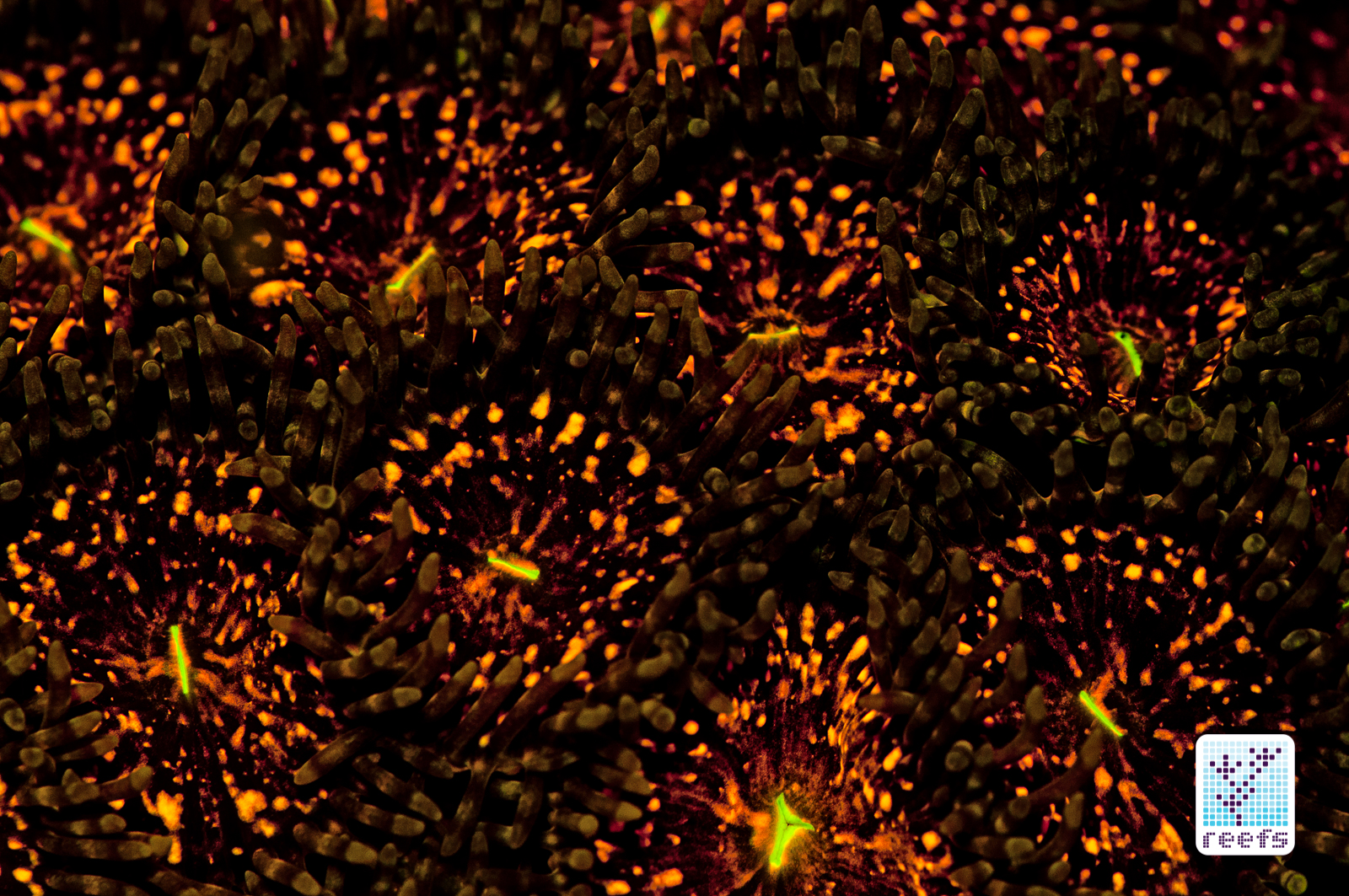

Go dark, and light the scene with fluorescence-exciting light to experience Zoantharia in an entirely new form. An alien world dominated by hues of green, orange, and red in an eye popping intensity only fluorescence can produce.

Zoanthids and Palythoa polyps go through a daily metamorphosis when exposed to the extensive blue light of aquarium LED moonlights, pleasing the eye with the otherworldly fluorescence they produce. Throughout the years of my practice in shooting zoanthids, I’ve experimented with various color gels, photographic filters, and post-production techniques to isolate the fluorescent pigments present in their tissue.

Keeping zoanthids in a reef tank

This paragraph needs a foreword disclaimer on my part: I’m no expert in keeping zoanthids in a reef tank, but rather a mere student of the art that, perhaps, never fully masters all its nuances. My experience is this: I’ve gone through hue waves of failures and successes in keeping zoas, and even when I have managed to grow them into colonies hundreds of polyps strong, I couldn’t point to a single method that allowed me to get there. I’ve read tons of articles on keeping zoanthids alive, participated in countless online debates with people claiming they’ve found the “Holy Grail” of zoanthid-keeping (be it a product or/and a methodology), only to come into a singular conclusion- there is no single approach that guarantees success in maintaining a zoanthid/palythoa dominated reef tank.

Please allow me to debunk some of the most repeated, alleged “recipes for success” in keeping zoanthids in captivity:

- Zoanthids don’t like strong light and a lot of flow- this is my favorite one. Please scroll down to the next paragraph to learn how ridiculous this claim is

- Zoanthids prefer high alkalinity levels- well, I don’t know about that. In my current setup, which recently went through a massive RTN event that killed most of my SPS corals, I lowered the Alkalinity to as little as 7 at times with nothing but great growth in my zoas and palys.

- Dosing iodine helps zoanthids/palys multiply faster- there’s no scientific evidence to that claim, at least none that I know of. People dose it declaring that they see results from doing so, but is it really something but an example of herd mentality? “This reefer doses iodine and his/her tank is full of zoas, therefore it MUST work”. I dose it too, because “Hey, maybe that’s the trick”, but I do so while being aware I may be fooling myself into thinking this is the magic potion that helps me with keeping zoanthids.

- Zoanthids love dirty water- yes and no. I’ve seen them growing beautifully in an SPS dominated aquarium, as well as in a algae farm of a tank, but my experience with them is that they don’t tolerate ultra low nutrient systems and rarely thrive long term in such tanks

- Zoas must be target fed to thrive- aren’t you target feeding them by default when feeding fish? Animals belonging to the order Zoantharia have little trouble capturing food suspended in water column, therefore target feeding them may not be necessary at all.

- Zoanthids and palys hate high light tanks- I have a couple of polyps of “Pink and gold” zoas, an offshoot of a mother colony residing in the bottom of my tank, growing at the very top of the tank and they are absolutely gorgeous compared to the ones growing near the bottom. I experimented with placing several zoa frags high in the water column and have never seen any negative effects of their proximity to the light.

Zoanthids are mysterious animals that change their growing habits in what seems to be random “scenarios”- I’ve shared my experience with several other people who have successfully kept and propagated zoas in their tanks and the one common reaction most of us have when zoa growth explodes is “Wow, how did that happen?” I can’t tell you what makes my zoa farm thrive, because every time I have success with them, they’re being kept differently. In my first tank, I had a barely working skimmer, dim PC lighting, and zero dosing, and the zoanthids and palys did well. The second time, I ran a SPS dominated, zero nitrates and close to zero phosphates aquarium, and zoanthids covered the bottom of that tank until one day they all started melting away. This time around, my tank got through a nasty RTN episode where almost all my hard corals disintegrated, only to make space for rapidly expanding zoa/paly colonies. I don’t know what makes them happy, but my observations while keeping them for several years has been that they like average water quality (nitrates below 5ppm and phosphates below 0.10ppm) in correct salinity (35ppt), good quality light (currently keeping them under Ecotech radion G4Pro LED panels), temperature in the 78-80 F range, and a strong but chaotic flow. If I had to bet on one thing that helps zoanthids the most, I would put it on flow. When I write “chaotic flow” I mean a strong stream of water in the tank that is constantly being broken apart by counter flow. I achieve it by having two main pumps mounted on the side panels of the tank, the flow of which is disrupted by another pair of slightly angled, less powerful wavemakers mounted on the back of the tank. That creates numerous eddies and rip tide-like flow patterns throughout the aquarium, which resembles their natural environment. Speaking of which…

Zoanthids in the wild

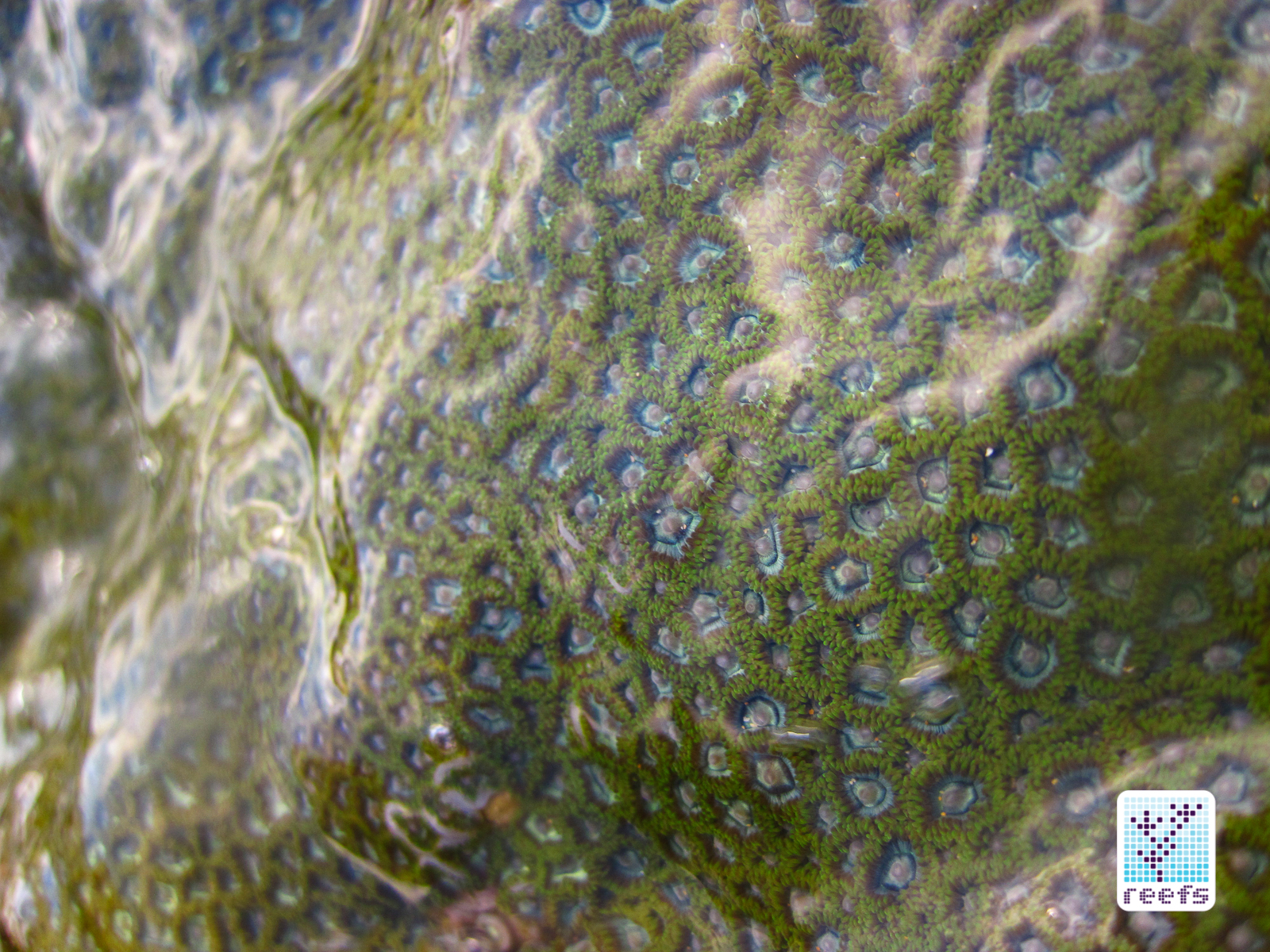

I’ve had the opportunity to observe zoanthids in their natural environment in two vastly different ecosystems- in the subtropical waters of the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Florida Keys, and in the isolated reefs of the Hawaiian Archipelago. Those two experiences changed my opinion about keeping zoanthids in captivity and both for the same reason, despite them being dramatically different environments. Here’s the thing-zoanthids thrive in extremes! I couldn’t believe my own eyes when I first saw huge mats of zoas growing in an intertidal zone mere yards from the beach on the island of Maui, being battered with waves in the morning when the tide was high, only to be exposed to air for hours during the low tide afternoon hours, with their polyps fully open. Plus, they weren’t ordinary brown Palythoa polyps, but rather beautiful pink and blue zoanthids that would probably yield a high price tag in the hobby. Fortunately, I documented it all, see for yourself:

On the contrary, the yellow colored Palythoa caribaeorum I witnessed while snorkeling off the beach of Key Colony Beach, FL and in the outer reefs surrounding the islands , thrived in the algae and silt covered seagrass mats in no more than 12 inches of almost still lukewarm water, as well as on the reef.

In both these situations, zoanthids and palys were looking healthy and covered vast areas of ocean floor, not minding the brutal wave action (in the case of the Hawaiian species) and unforgiving sun rays (in Florida) as if they were perfectly adapted to these conditions. These “confusing” findings further cemented my belief that we know very little about zoa husbandry and that we are still in the infancy of understanding their demands. However, it’s truly fascinating that we are able to provide for zoas and palys in the confines of a home aquarium, despite the fact that the environment we create for them, more often than not, is drastically different than their natural habitat.

Conclusion

I started this write-up to showcase my years of photographing zoanthids in the aquarium setting, but I couldn’t stop myself from providing some (hopefully) useful information about my experience in keeping them in captivity. I hope you enjoyed this one and what better way to end it than with a solid gallery of photographs, right?

Thanks for reading.

References:

Aquarium photography guide Part I by Marcin Smok

Aquarium photography guide Part II by Marcin Smok

Aquarium photography guide Part III by Marcin Smok

Aquarium photography guide Part IV by Marcin Smok

Aquarium photography guide Part V by Marcin Smok

Identify This: Zoanthids by Drew Wham Reefs Magazine Issue Fall 2013

This is very beautiful.