Over the past decade, researchers investigating the genetics of coral evolution came to a startling conclusion—the traditional classification used for stony corals, based on skeletal morphology, was horribly (almost comedically) inaccurate. Since then, every year has brought along a major new revision that has turned the established nomenclature on its head. Familiar names like Favia and Scolymia were radically redefined (neither of these occurs in the aquarium trade now), and now the newest group to get this treatment are the lobophylliid corals, a family which didn’t even exist up until a few short years ago.

This was originally described in 1985 as Australomussa rowleyensis. It became Parascolymia rowleyensis in 2014, and now it’s Lobophyllia rowleyensis. Credit: Max Reef

Lobophylliidae contains a hodgepodge of LPS corals common to the aquarium trade: acans and lords, many of the chalices and open brains, scolys, doughnut coral, meat coral and a few others. All occur in the Indo-Pacific and all have large spines along their septa (which have a nasty tendency to poke through shipping bags and damage the coral’s delicate tissue). This is in contrast to the Mussidae (which sport smaller spines of a different morphology), to which they formerly belonged and which are now restricted to the Atlantic. Since this family was established in 2009, studies have indicated that its genus-level classification did not reflect the true evolutionary history of these corals. This problem has slowly been getting addressed over the course of many different papers, such as with the recognition of Sclerophyllia and Homophyllia and several other changes, but, up until now, there has not been a single, exhaustive look at the entire group.

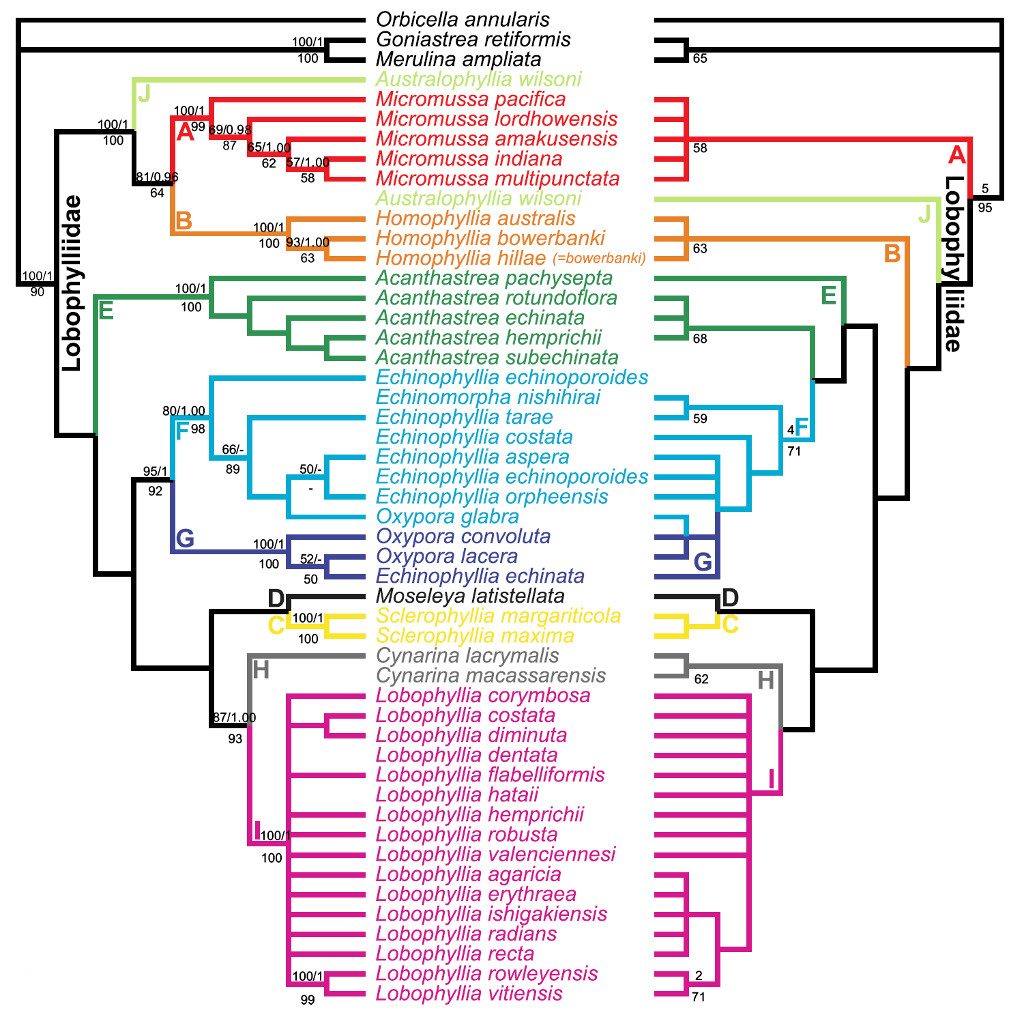

Phylogenetic relationships of the Lobophylliidae based on genetics (left) and morphology (right). Credit: Huang et al 2016

But that changed with the recently published and long-awaited morphological revision of the lobophylliids (Huang et al 2016). This monumental effort built upon previous genetic studies by adding an in-depth look into the skeletal differences that unite and differentiate the major evolutionary clades that had already been found. In doing so, many species were to find themselves reclassified. For the serious student of corals, this paper (as well as earlier revisions to the Mussidae and Merulinidae) is a must-read. Much of it is couched in an almost indecipherable dialogue of unfamiliar terminology, but it is worth the effort to understand what is being presented here, as it allows us to really appreciate what separates one group of corals from another. That being said, I won’t burden you, dear reader, with any of this morphological minutia. Presented here is a brief summary of the taxonomic changes.

- Micromussa was formerly an odd little genus that contained just a single species of note to aquarists, M. amakusensis. This coral looks more or less like a mini Lord’s Coral, and, as it turns out, these two are close relatives, now classified together. Added to this mix is the newly described Mini Scoly (M. pacifica) and an Indian Ocean relative (M. indiana). Another interesting addition is a M. multipunctata, which had formerly been included in Montastraea, a genus now found only in the Atlantic and which belongs to an entirely different family. There were also two other species of Micromussa that nobody ever talked about, and these have been relocated to Acanthastrea (for A. minuta) and Goniopora (for G. diminuta). This latter move is almost unbelievable, as Goniopora and Micromussa belong to vastly different lineages, roughly equivalent to classifying a bird and a bat together for sharing wings. It’s even more egregious in that it appears the type specimen of G. diminuta is identical to the common aquarium species G. somaliensis. So, to recap, the only reason that “Micromussa diminuta” ever existed was because somebody had horribly misidentified a specimen of Goniopora somaliensis. Yikes.

- Homophyllia was reclaimed from synonymy in an earlier paper and used to classify the beloved scoly, which had formerly been included alongside two similarly shaped Atlantic species that now constitute the genus Scolymia. This leaves us in the awkward position of having a well-established common name that conflicts with the new taxonomy. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ But a new wrinkle to this story is the inclusion of colonial species, formerly known as Acanthastrea bowerbanki and A. hillae. These corals have considerably larger polyps than any of the others acans, so it makes some sense that they would find themselves alongside the scoly. It was also shown that hillae and bowerbanki are essentially the same coral, both genetically and morphologically, with the end result being that the former species is no longer recognized. All those large-polyped acans are now Homophyllia bowerbanki.

- Australophyllia is the new home of the Wilsoni Brain Coral, an evolutionarily distinct lineage which is found only around the subtropical reefs of Western and Southern Australia. This colorful coral, whose price tag is often bigger than its shelf life in captivity, was found to have some interesting peculiarities to its morphology, including the presence of Hydnophora-like bumps between the polyps (termed monticules) that had not previously been noted. Along with Micromussa and Homophyllia, these corals together form one of the major lobophylliid clades.

- Acanthastrea has been overhauled considerably and now consists mostly of drab species that look somewhat like a spinier version of the distantly related Favites brain corals. The fluorescent green and orange species that regularly enter the aquarium trade (echinata, subechinata, rotundiflora, hemprichii) are still grouped here, but the most familiar of the acans—the Lord’s Coral, AKA, the “acan lords”—is now moved into Micromussa. For some insight into why that move was made, see my earlier discussion on the matter. The only other acans that aquarists were likely to be familiar with have also been moved, with A. bowerbanki and A. hillae now moved alongside the scoly in Homophyllia. Acanthastrea also swapped species with Lobophyllia, with the former L. pachysepta now registered as an acan and A. ishigakiensis as a lobo. The times they are a changin’. And, lastly, the former A. faviaformis has now been moved into Dipsastraea, which was itself formerly Favia… which means that the Favia-like appearance alluded to in its name was due to it actually being a Favia, even though it isn’t Favia anymore. Got it?

- The lobophylliid chalice corals remain a source of confusion, and, unfortunately, this study was unable to provide any real clarity on the matter. The two major groups, Echinophyllia and Oxypora, are not distinct from one another in their genetics, as O. glabra appears to be more closely related to Echinophyllia. However, morphology seems to suggest otherwise, so the matter remains unsettled for now. A few of the rarer species have yet to be studied adequately, and it will probably only be when these get examined that there will be closure on the matter. The monotypic Echinomorpha nishihirai also awaits genetic study, so stay tuned for future changes to these corals.

- Moseleya, Cynarina, and the recently revived Sclerophyllia all remain the same, each representing fairly distinctive clades with few species. One of the long-standing mysteries among these corals is whether the Meat Coral, familiar to aquarists under the name Acanthophyllia deshayesiana, is a real species. Skeletal morphology seems to indicate no, but, given the considerable difference in its tissue compared to the bubblier Cynarina lacrymalis, this is a surprising result. For now, the two have to be lumped together, but I have my suspicions that genetic study might eventually suggest otherwise. The coral formerly known as Indophyllia maccassarensis still remains recognized as a species, though it now resides in Cynarina as the only other valid taxon. There has been a suggestion from aquarists that this coral might represent a hybrid of the lacrymalis and deshayesiana morphs of the Meat Coral. I, for one, haven’t the faintest idea what macassarensis is supposed to look like, and I suspect that the same holds true for everyone else tasked with identifying this coral. From what I’ve seen, just about any aberrant looking Meat Coral is liable to find itself identified as C. macassarensis by aquarium retailers, but this diagnosis is meaningless without a study of the underlying skeletal structure. Hopefully, we’ll someday have a fulfilling answer to all the questions surrounding these abundant, colorful and gargantuan corals.

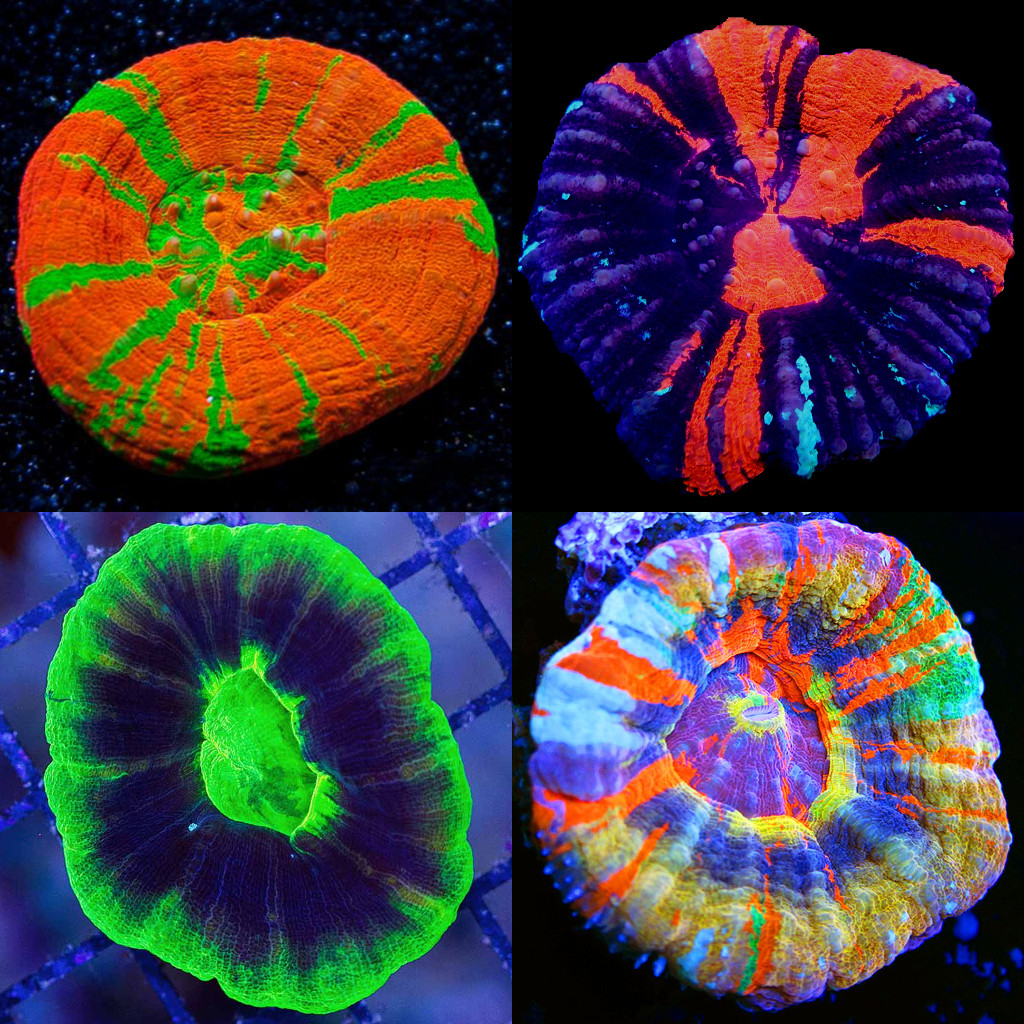

- Lobophyllia has increased by leaps and bounds, as it now includes the species formerly included in Symphyllia, as well as the briefly lived genus Parascolymia. The latter included a pair of species, which had long been known under the names Scolymia vitiensis and Australomussa rowleyensis, but these closely related species nestle cozily within the Lobophyllia lineage. The same holds true for Symphyllia, which had been treated separately for having colonies formed of long, meandering valleys whose walls joined together; however, it was found that this trait had multiple exceptions (e.g. S. valenciennesi, L. hataii), making the distinction unclear. Genetically, the nineteen recognized species in Lobophyllia appear quite closely related, and it may be some time before we fully understand the interrelationships here.

This is Dipsastraea faviaformis, the Favia-like acan that is now classified as a “Favia” instead of an acan, even though that genus isn’t Favia anymore. Fml. Credit: Charles Veron / Corals of the World

Huang, D., Arrigoni, R., Benzoni, F., Fukami, H., Knowlton, N., Smith, N.D., Stolarski, J., Chou, L.M. and Budd, A.F., 2016. Taxonomic classification of the reef coral family Lobophylliidae (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Scleractinia). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 178(3), pp.436-481.

Awesome!