Thor amboinensis, the Sexy Shrimp, is a colorful and highly erotic crustacean familiar to aquarists and divers alike, beloved for the sensual manner with which it shakes its derriere. This tiny caridean is typically encountered in close proximity to sea anemones and is alleged to be one of the few reef organisms to have a worldwide distribution in tropical waters. For such a tiny shrimp, it certainly does seem to get around, but now some exciting new research is calling into question this basic assumption. Hold on, dear reader, because the ocean is about to get a whole lot sexier.

In a new study by Titus et al. appearing in the Journal of Biogeography, populations of Thor amboinensis from 30 locations scattered across the globe were sampled for a variety of genetic markers. The results that came back revealed that, instead of a single species of sexy shrimp, there are more likely to be at least 5 major geographic lineages. These break down into the usual hotspots for endemic speciation: the West Atlantic, the Red Sea, the West Pacific, Japan, Polynesia.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B5GK1JAa4LQ

But despite the strong genetic signal, these authors hesitated to recognize any new taxa, stating that “no obvious differences in morphology or colour pattern exist among [sexy] shrimps (adult or larval) from any biogeographical region.” Ah, but au contraire! Is this really true, or have we simply failed to notice and document the morphological traits that might serve to separate them? To put this to the test, I scoured every nook and cranny of the internet, staring at thousands upon thousands of specimens—divers REALLY do like to photograph this shrimp. It was hard, sexy work, but, as I’ll now show, there are actually quite a few easy to spot differences which confirm the presence of several distinct species here.

The true Thor amboinensis was described from specimens collected at the Indonesian island of Amboina (now generally known as Ambon). These can seemingly be recognized by a single trait not found in any of the other populations; namely, the thickened segment at the base of the smaller first antennae (the “antennular peduncle”) has a broad white band near its tip. Specimens possessing this occur west to at least Bali, north into the main islands of Japan, east to the Marshall Islands, and south to the Great Barrier Reef, Fiji, and French Polynesia. There are some important exceptions to this which I’ll discuss later, but, for the most part, there appears to be a single homogenous species (both morphologically and genetically) in the West and Central Pacific.

Thor cf amboinensis, from Maldives. Note that the white spots and saddles are highly variable in all populations, often forming an extra abdominal spot. Credit: Daniel French

When we cross over into the Indian Ocean, we encounter a similar looking shrimp, save for one important difference… the antennular peduncle is lacking the characteristic white band. This never varies and provides clear evidence for speciation between these ocean basins. Specimens with this phenotype are documented throughout the Red Sea and south to Durban, the Maldives and Chagos, the Andaman Sea, and as far east as Bali (and possibly Flores).

Specimens at Bali are sympatric with the true T. amboinensis, but, based on their relative abundance in photographs, seem considerably less common. Hybridization almost certainly takes place, though mixed-species groups have yet to be observed. The antennular peduncles which diagnose these two presumed sister species may function in mate recognition, as these structures are readily visible and made especially prominent by being vibrated during their “sexy” dance.

Thor cf amboinensis, from Canary Islands. Credit: Fco. Javier Lindo Martín

When we move over into the Atlantic, some new differences crop up. Specimens from the Canary Islands off Northwestern Africa are at first glance comparable to the Indian Ocean T. cf amboinensis, as they too have a mostly yellow antennular peduncle. The key traits to look for here are the colors of the antennal flagella and the legs. In both of the Indo-Pacific populations, the legs feature a contrasting red stripe of variable intensity and the antennal flagella are red throughout. On the other hand, the Eastern Atlantic population has solidly yellow legs, and the antennal flagella are pale at their base, becoming red towards the tip.

In the Western Atlantic, an even more obvious species can be found. Again, in this population the legs and antennular peduncles are predominantly yellow, but this time the antennal flagella are clear, with numerous red bands along their length. This difference has been noticed in at least some field guides, but it’s quite surprising that it hasn’t caught the eye of taxonomists yet.

Examining the genetic analysis of Titus et al. 2018, we find a strong agreement between the morphological difference that I’ve just noted and their phylogenetic data, but with some important caveats. Unfortunately, there isn’t any genetic data for the Eastern Atlantic, but, based on what has been observed in other groups of reef organisms, we can reliably expect it to form a close sister lineage to the Western Atlantic.

The Indian Ocean population is also poorly sampled, with the only specimens in their dataset being from the Red Sea. There was additionally a single aberrant specimen from Bali which grouped separate from nearly everything else. One plausible explanation for this is that there are really multiple species present in Indian Ocean, possibly with one restricted to the Red Sea or the Western Indian Ocean and another occurring from the Persian Gulf to the Sunda Shelf. This would match the pattern seen in many reef fish complexes, but further sampling is needed.

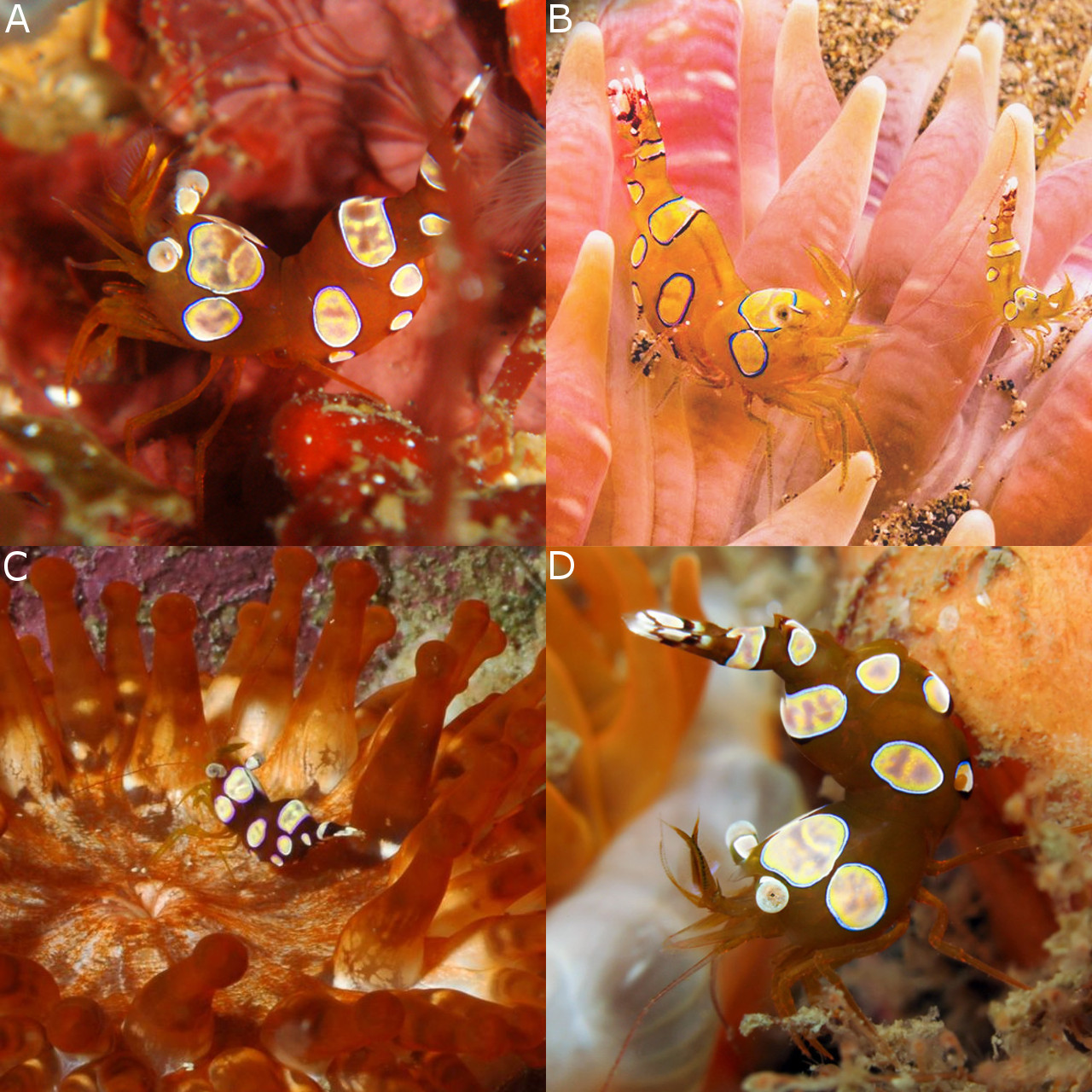

Thor cf amboinensis. A: Izu, Japan (Izuoshima Dive Center) B: Hawaii (David Fleetham) C: Galapagos Islands (Graham Edgar) D: New South Wales, Australia (Brian Mayes)

The most confounding issue relates to a small number of specimens from Japan and parts of Polynesia that would appear to form a pair of unique lineages. It’s certainly not surprising that there might be endemic species here, but, when we look at the phenotypes present in these locations, we find a mixed signal. Japan does indeed have a second variety of sexy shrimp which can be recognized in lacking the subapical white bands of the antennular peduncle. These occur quite commonly around the Izu Peninsula, with scatter records at Kashiwajima and Taiwan. However, these appear to be fully sympatric with the typical Thor amboinensis.

A similar situation occurs in Polynesia, though our data for this region is rather sparse. Genetically sequenced specimens (originating from Moorea, the Marquesas, Hawaii) group within the larger lineage of Pacific Thor amboinensis, but, importantly, a few don’t, including ones from the Marquesas, Palmyra Atoll and the Gambier Islands. When we look at photographed specimens, we find the white-banded antennular peduncles present in a specimen from Bora Bora (near Moorea), but those from the Marquesas and Hawaii have the aberrant unbanded peduncles. This perplexing phenotype also pops up in the Galapagos Islands, and might be expected at the few other locations in the Eastern Pacific from which this shrimp has been reported.

And just to throw a little more fuel on the fire, all of the specimens documented from the subtropical portions of Eastern Australia are likewise of the unbanded phenotype, while those found on the Great Barrier Reef are of the Thor amboinensis type. There have also, on very rare occasion, been unbanded specimens observed around the Lembeh Straits of Sulawesi and Fiji. It becomes quite challenging to find an explanation for this unusual discordance between these various data (biogeographical, genetic, morphological).

Perhaps there are two widespread species that co-occur throughout most of the Central Pacific? Alas, this region is among the least-documented by diver photography, so it’s hard to know the true extent and abundance of either phenotype. Another explanation could be that a subtropical species exists, as most of the unbanded Central Pacific specimens come from or near cooler reefs (with the exception of those from Fiji and Palmyra Atoll). Or is this just a group of allopatric (i.e. non-overlapping) populations that are deeply introgressed (i.e. hybridized) with their neighbors? This might explain why only certain peripheral populations in the Pacific show this phenotypic plasticity. Until more data becomes available, it’ll be challenging to determine the true answer to this sexy evolutionary puzzle.

- Titus, M. T., Daly, M., Hamilton, N., Berumen, M. L. and Baeza, J. A., 2018. Global species delimitation and phylogeography of the circumtropical ‘sexy shrimp’ Thor amboinensis reveals a cryptic species complex and secondary contact in the Indo‐West Pacific. Journal of Biogeography, 1-13 DOI: 10.1111/jbi.13231

And now for some sexy video footage…

- Egypt

- Indian Ocean (Maldives or Seychelles)

- Dahab, Egypt

- Florida

- New South Wales, Australia

- Japan

- Miyakojima, Japan

- Guam

- Caribbean

0 Comments