The Maldives has been a mecca for divers and tourists seeking white sand, palm trees and luxury resorts for several decades and for a country with only a fraction of a percentage of its territory able to be called dry land, its punches well above its weight in attracting the tourist dollar. Once the preserve of only the wealthiest (and in the main Europeans), the Maldives is increasingly being opened to the world and global mass tourism. For the local economy, this is no doubt a good thing, but for the reefs and their wonderful biodiversity, it’s not necessarily good news. Time will tell if a balance is kept between the Maldives’ ‘unspoilt paradise’ reputation and tourist development across the 1200 or so individual islands that make up the entire archipelago. So far, it’s still wonderful and many resorts are doing what they can to be sustainable and considerate to the reefs.

To understand why the Maldives are so impressive, it’s worth looking back a little to understand how the archipelago was formed: Imagine a chain of volcanic islands, many millions of years ago, rising from a ridge in the Indian ocean. Imagine each island with its complicated coastline surrounded by a fringing reef and perhaps some smaller offshore reefs forming around it for good measure. Add the sound of waves breaking and seabirds calling if it helps. Then imagine the islands’ volcanoes cooling down and the weather, wind and rain eroding them to nothing, yet the reefs, self-repairing as they are, continue to grow and prosper. Add a little tectonic movement with the sea floor lowering perhaps and you are left with the shadow of a landscape, picked out in living coral. This in the very simplest of terms is how an atoll forms.

On a large enough scale, you can see the 12 individual atolls that form the Maldives’ overall structure, but move in more closely (try it in Google Earth) and the structures become far more complex. Each atoll is riven with channels that allow the currents and tides of the Indian ocean to wash into central areas. You can make out individual islands, some green with vegetation and some mere piles of sand that come and go. Under the surface hints of turquoise indicate submerged reefs and in the lagoons, darker patches suggest seagrass meadows. It’s complicated, diverse and remarkably wonderful, with seasonal factors such as monsoon currents from the north and local geography combining to add seasonality to the mix.

A typical uninhabited Maldivian island, never more than a few metres above sea level. Photo by Richard Aspinall.

To explore the Maldivian ecology in a short article means I’m only able to look at the simplest and most obvious features, but I hope it is of interest nonetheless.

I’ll start on shore. As you can imagine the terrestrial ecology of the Maldives is somewhat limited. There’s not much space after all and very little fresh water in the dry season. Beyond a few species of migratory seabird and fruit bats the skies are empty and the plant ‘list’ is also quite short it appears, though Coconut palms, Fan Flowers and Beach Hibiscus are common. For me though, it’s on the beach where things start to get interesting, various crabs and hermits are commonplace and a walk along the beach will reveal various ‘washed up’ treasures.

These tough critters can survive heat, salt and sand. They are at risk from becoming trapped in discarded plastic bottles. Photo by Richard Aspinall.

On some islands, you can also see plenty of juvenile Blacktip Reef Sharks that swim within metres of the shore and will swam close by as you paddle. Never more than forty or fifty centimeters they are harmless and very timid.

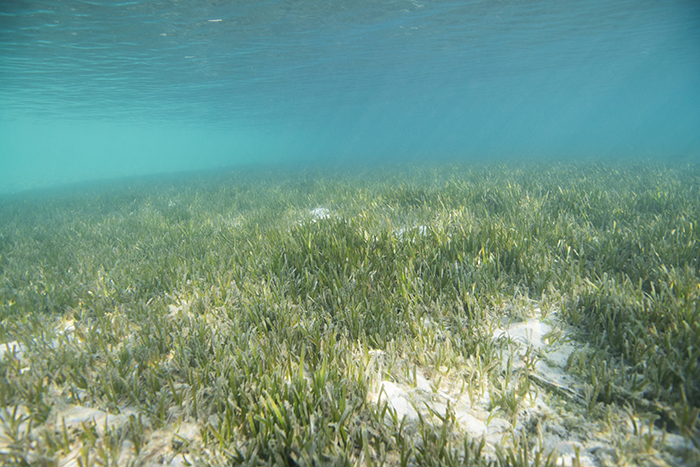

Beyond the low water mark is the typical coral sand of the tropics. Lots of flattish particles indicate the presence of Halimedia further out on the reef. It’s easy to overlook this area, but there’s a lot going on, especially if you include the seagrass meadows. The meadows host numerous fish species, from Ghost Pipefish to juvenile wrasse. They also seem to hold an awful lot of sea cucumbers, busy controlling nutrient levels as they go.

Seagrass meadows help process nutrients and provide habitat for a myriad of species. They are also a favorite food source for some turtles. Sadly, some resorts remove them to provide more sand area. Photo by Richard Aspinall.

The sandy areas are especially interesting to explore at night, when fish and invertebrate life is more active, though a snorkel under a pier during the day can reveal similar species sometimes.

Conus litteratus. Photo by Richard Aspinall.

Anyone got a clue what this is? Photo by Richard Aspinall.

I’m going to take a moment out here as it might be a good idea to look at very shallow offshore reefs before we look at the fringing reefs.

As you can imagine, in this complicated environment, there are reefs of all depths, but to help with the confusion, the good folk of the Maldives have decided that reefs that are just below the surface are called Giris. Some of these are quite small and are ideal for snorkeling around. You can swim around the a giri and enjoy the brightly lit shallows and look out into the blue where shoals of snappers and jacks are joined by the occasional Eagle Ray. The upper areas of giris are often dead coral, especially in areas that suffered from the bleaching event last year, though some robust and massive corals persist. Around the edges, you can find a rich assortment of fish, from anthias to butterflies and some pretty amazing tridacnids.

Photo by Richard Aspinall.

A typical shallow giri. This one has lots of algal growth and happy Powder Blue Tangs. Photo by Richard Aspinall.

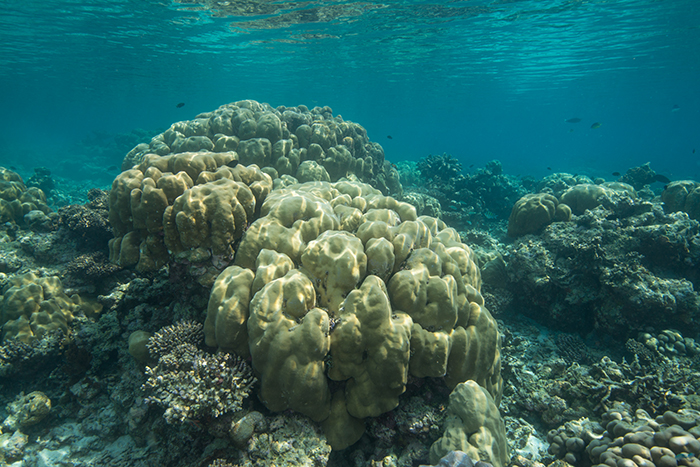

Some massive corals, like this Porites (P. lobata perhaps?) are real survivors. Photo by Richard Aspinall.

A gorgeous shoal of Red Tail Butterflyfish shelters amidst the old coral. Photo by Richard Aspinall.

The next category of reef I want to look at are thilas. These are around fifteen metres or so deep and are either very small or part of larger reef structures that will take multiple dives to explore.

Being a little deeper and receiving cooler ocean currents means that thilas tend to be richer in life than giris and the very best example is a wonderful site I visited in the north east of the Maldives, called Anemone Thila. I was looking forward to seeing this site after being told about it by my guide and how it was best to visit when the weather was cloudy. I wasn’t sure why, but took her word for it, and on a rainy day we dropped onto the reef and I immediately realized what she meant. In dull light the ‘nems closed up partially to reveal the colours on their mantles. I can honestly say, I have never seen as many anemones in one place, they were everywhere.

As you can see the ‘nems come in a wide range of colours and as I watched the clowns swim from hoist to host I had to wonder what it was that made this particular spot ideal? Presumably, it’s a combination of factors, not least being current and light, but what about the relationships between the individuals? Who was related to who? A truly fascinating place.

Photo by Richard Aspinall.

Amphiprion nigripes. Photo by Richard Aspinall.

Returning back to fringing reefs reveals underwater ‘landscapes’ as diverse as they are numerous. Categorizing them is near impossible, but there are some common features that are commonplace. Take bommies for example. I really enjoy exploring a series of bommies, especially those amidst sand. In the sandy areas, you can find Garden Eels, Shrimp gobies and larger stuff like rays and on the same dive you can focus on the bommies to enjoy the smaller stuff within the coral. For me, this is ideal, with a macro lens mounted on my camera I can spend an awful lot of time circling a bommie a few metres across, shooting away.

On one bommie I finally found a juvenile Emperor Angel. I’ve plenty of photos of the adults, but I’ve never yet managed to find a juvenile fish to capture them in their childhood coloration. On the same dive, I came across a tiny Yellow box fish and the endemic Collar Blenny (Ecsenius minutus). I also found a pipefish (Corythoichthys nigripectus) looking at me whilst I waited for the Emperor Angel to pluck up courage to emerge from its hideaway.

Yellow Boxfish (Ostracon cubicus). Photo by Richard Aspinall.

This fish is just beginning to transition, note the yellowing of the dorsal region. Photo by Richard Aspinall.

C. nigripectus (likely). Photo by Richard Aspinall.

Farther out from the beach, and indeed a little deeper, you come across zones where fish life seems to really increase and the coral becomes a little more consistent. Sholas of anthias, including Pseudanthias squamipinnis, P. ignitus and P. evansi are often found together in high current areas, feeding on the passing food particles that contribute to making Maldivian visibility so poor. The latter fish can form quite large shoals, and is often seem amidst coral branches when young.

P. squamipinnis with P. evansi to the rear left. Photo by Richard Aspinall.

The gorgeous Pseudanthias ignitus. Photo by Richard Aspinall.

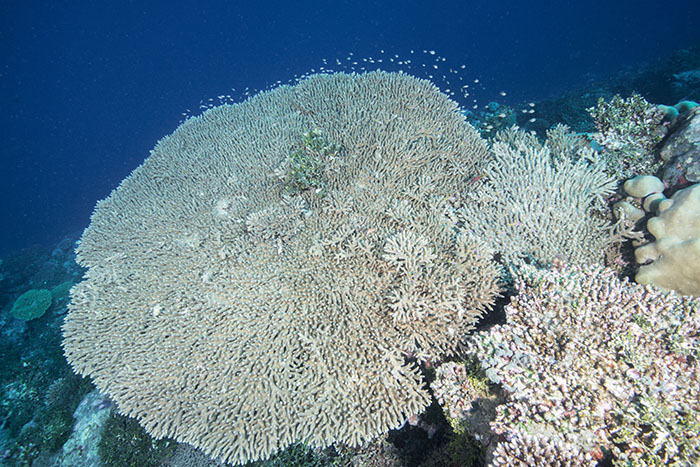

The coral, depending on the reef and degree of earlier bleaching can be quite astounding, with large areas covered in tabulate acropora, with some colonies more than a metre across. Some stands of branching acropora are also particularly attractive. What you tend not to get though, is a great deal of color. Dull brown and creams with some hints of pastel shades are as colorful as the corals get. Encrusting sponges and Tubastrea certainly make up for it though.

In this image, various coral species have colonized a dead tabulate acropora. Photo by Richard Aspinall.

Fish life is splendid as well, indeed there are some species that are quite a nuisance. Shoals of glassfish and silversides can be very attractive to watch as they flash silver in their thousands, but when you’re trying to shoot a static subject and they’re using you for shelter, they are a real pain.

Possibly Acropora clathrata, this coral was well over a metre across. Photo by Richard Aspinall.

This little scorpionfish was well camouflaged. Photo by Richard Aspinall.

The glassfish helped this image. Note the nephtheid coral, they are not common in the Maldives. Photo by Richard Aspinall.

Away from the reef and into the blue there are plenty of larger fish to watch out for; snappers, jacks, trevally and the odd Grey Reef or Whitetip Reef shark are easily spotted as are batfish that often come close and investigate new arrivals. Amidst the corals butterflyfish graze and there’s always a few Moorish Idols that I have yet to photograph well.

Photo by Richard Aspinall.

Looking more closely reveals every photographers’ favorite, the hawkfish. These sedentary predators are easy to approach and always worth shooting. This was the first time I managed to shoot the Arc eye Hawkfish, a fish which can be anything from russet to a pale salmon. On the same dive, I ‘bagged’ Oxycirrhites typus and Cirrhitichthys oxycxephalus.

Longnose Hawkfish (O. typus). Photo by Richard Aspinall.

Arc eye or Monocle Hawkfish Paracirrhites arcuatus. Photo by Richard Aspinall.

Diving on a night reveals an entirely different world of course and its truly amazing to see the black Tubastrea micrantha come alive. I should mention that this coral can be found in large tree-like structures on some sites, though the best I found was growing on the superstructure of a shipwreck.

An amazing ‘spray’ of T. micrantha. Photo by Richard Aspinall.

So that’s it, a very brief tour of some of the highlights of the Maldives and a quick overview of the reef structures. with some of my images.

0 Comments