By Tony Vargas

A few years ago, a couple of Australians brought Tubbataha to my attention during a dive excursion in Puerto Galera, the Philippines. Their unremitting rave about the incredible vastness of Tubbataha’s landscape, its rich coral valleys, its colorful walls, and its strong yet mature fish populations captured my attention. Their persuasive argument and a little research convinced our group to plan a trip there on a live aboard the following year.

Despite Tubbataha Reef’s remote location, it faced many of the same perils reefs in close proximity to man have suffered. In the early eighties over- fishing, poaching, and the use of explosives destroyed most of this coral reef paradise. On August 11 1988, Tubbataha Reef National Marine Park was formed under Presidential Decree No. 705. This was the first National Marine Park in the Philippines and was met with strong opposition from many of their local people. This Decree sealed off 33,200 hectares from man’s destructive behavior, anyone caught in illegal activities would face serious criminal prosecution. In 2006, Presidential Proclamation No. 1126 expanded the park from 33,200 hectares to 96,828, making this park one of the largest protected bio nurseries in the world.

Despite Tubbataha Reef’s remote location, it faced many of the same perils reefs in close proximity to man have suffered. In the early eighties over- fishing, poaching, and the use of explosives destroyed most of this coral reef paradise. On August 11 1988, Tubbataha Reef National Marine Park was formed under Presidential Decree No. 705. This was the first National Marine Park in the Philippines and was met with strong opposition from many of their local people. This Decree sealed off 33,200 hectares from man’s destructive behavior, anyone caught in illegal activities would face serious criminal prosecution. In 2006, Presidential Proclamation No. 1126 expanded the park from 33,200 hectares to 96,828, making this park one of the largest protected bio nurseries in the world.

Shortly after the Decree was enacted, a Ranger station was erected to monitor the ins and outs of the park. With the assistance of the Philippine Navy and the watchful eye of the Ranger station, 24 hour police presence was accomplished. Boats wandering into this closed off area without the granted permission of the Ranger station or the Navy would risk serious consequences. A situation arose back in February of 2002, when the Philippine Navy and the Philippine Coastguard apprehended four Chinese fishing vessels. Jail time was served, vessels were confiscated and fines were issued, confirming that these offenses would not be tolerated and swift punishment would be implemented.

Tubbataha Reef is a rare gem centrally located in the Sulu Sea, 98 nautical miles southeast of Puerto Princesa City on Palawan Island. The reef consists of two massive atolls spread apart by a large channel seven kilometers wide. On the northeast tip of the largest atoll is Bird Islet, and on the southwest end of the atoll is the Ranger station where at low tide a sandy beach becomes exposed to the elements.The name Tubbataha comes from the Samal,a seafaring people of the Sulu region, and means ‘long reef exposed at low tide’.

The smaller atoll is located southwest of the Ranger Station and is separated by a seven-kilometer channel. At the southern end of the smaller atoll is a small island with a solar powered lighthouse, trespassing is illegal.

In 1993, Tubbataha received one of the world’s highest honors for its achievements–the UNESCO inscribed Tubbataha Reef as a World Natural Heritage Site. This inscription opened the door to more tourism and helped confirm the many lessons learned by creating this park.

Finding a live aboard company that would understand the needs of a group of aquarists and what we would be looking to accomplish proved to be quite challenging. In addition, we looked for a company that would understand the landscape of the reef, where are the lagoons, where are the reef flats, where are the stony corals, where are the large schools of fish, and most importantly how do we best avoid SHARKS. The company that met all our needs was Expedition Fleet, and they provided us with a knowledgeable staff and a live aboard boat named the Apo Explorer. This boat came with all the modern day accommodations, such as hot and cold water, air conditioned rooms and individual bathrooms in addition to a cook, a mess hall, and most importantly dive gear.

Finding a live aboard company that would understand the needs of a group of aquarists and what we would be looking to accomplish proved to be quite challenging. In addition, we looked for a company that would understand the landscape of the reef, where are the lagoons, where are the reef flats, where are the stony corals, where are the large schools of fish, and most importantly how do we best avoid SHARKS. The company that met all our needs was Expedition Fleet, and they provided us with a knowledgeable staff and a live aboard boat named the Apo Explorer. This boat came with all the modern day accommodations, such as hot and cold water, air conditioned rooms and individual bathrooms in addition to a cook, a mess hall, and most importantly dive gear.

With much of our trip well planned out, at least a year in advance, we commissioned the assistance of a PADI master instructor Louis Claver, owner of Boracay Scuba. Louis travels with our group on a continuous basis to different dive sites around the Philippines and has become more of a brother than a Dive Master we rely upon. Bear in mind, that Expedition Fleet provides PADI experts Dive Masters with their excursions, but we are a little more demanding than most when we dive as a group.

I alone require the assistance of my own Dive Master–this has become a necessity since I am typically the only one taking pictures underwater. When taking photos you tend to observe the landscape a little closer than most and have a tendency to slow the progress of the group. Dive Masters pay close attention to my buoyancy and adjust me accordingly allowing me to focus all my attention on the shot. They also assist in finding and pointing out the unusual that can be easily overlooked.

I arrived in Manila after traveling almost 33 hours, took a nap, showered, and headed to the airport were I once again embarked on another airplane for a three-hour flight to Palawan Island. We landed in Palawan and stayed at a hotel in Puerto Princesa City through the night and headed to the boat in the morning. With an early wake-up call, we all arrived at the pier with plenty of time and I observed and pointed out how clean the dock is with all these large and small boats around. The other interesting fact in addition to the tremendously clean water was the thousands of Blue-green Damsel (Chromis viridis) swimming near the water’s surface.

We board the Apo Explorer and journey forward toward Tubbataha Reef. We lounged on its spacious deck, entertained ourselves in stimulating conversation, and enjoyed our ride to coral paradise. We observed countless Dolphin and Whales from the ships spacious bow and eight hours later, we are within visual distance of the Ranger station. The boat Captain radioed the Ranger station and requested permission to visit the park with 12 SCUBA divers. He also requested permission for a short tour of the station.

We board the Apo Explorer and journey forward toward Tubbataha Reef. We lounged on its spacious deck, entertained ourselves in stimulating conversation, and enjoyed our ride to coral paradise. We observed countless Dolphin and Whales from the ships spacious bow and eight hours later, we are within visual distance of the Ranger station. The boat Captain radioed the Ranger station and requested permission to visit the park with 12 SCUBA divers. He also requested permission for a short tour of the station.

Eager to dive, I began preparing my underwater housing, strobes, and camera for our first dive on Tubbataha Reef. On this trip, I brought with me larger and stronger strobes than the ones I used on the Apo Reef trip. I was advised to bring a few wide-angle lenses and a pair of powerful strobes–the water clarity was better here than in Apo and this would assist in producing more robust landscape photos.

When I first enter a new environment, I strategically position myself in a dormant or very inactive state offering me the opportunity to hover for landscape photos. These types of photographs recapture the emotions I feel the moment I enter these new surroundings and affords me with the opportunity of a possible revisit to areas overlooked.

Entering this liquid atmosphere for the first time, I immediately noticed the incredible clarity of the water; Dive Master estimations put visibility at around 125 feet. The clarity of this environment demonstrated how vast this coral landscape was, how much larger the schools of fish seem, and how tremendously vivid the reflection of the sun’s glitter lines cast over this massive coral real estate. Diving deeper and closer to the reef the fish did not shy away as they swim ever so closely to examine us, the foreign invaders. Water temperature hovered at 78° with the occasional rush of cold currents, which swept through the reef from the deep. It was interesting to watch fish purposely dart in and out of these cold water drifts to grab the occasional delicacy these currents provide.

On our first dive, I realized how this beautiful coral paradise was in a constant struggle with its own semi-contained environment. I witnessed corals continuously fighting for territory, looking to dominate a portion of the coral reef structure. If a coral could not dominate its neighbor on a side-by-side conflict it would take a different approach and crawl over its opponent. Nevertheless, these are the signs of a vibrant and healthy reef.

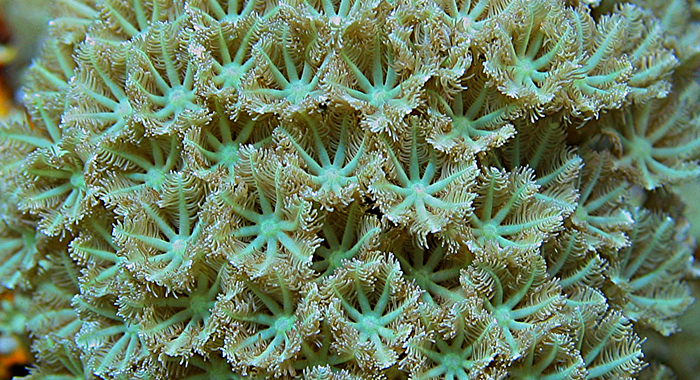

Most coral reefs are dominated by small polyp stony corals (SPS) and Tubbataha is no exception. Largely dominated by Acropora and Porites, these corals have a strong foothold on the landscape and were clearly visible to us on our first dive. We encountered hectares upon hectares of underwater rolling hills and reef flats teeming with Acropora and Porites.

Speaking of Acropora, clearly my favorite genus coral, there were several species I encountered that deserve some attention: Acropora abrotanoides a sandalwood colored specimen with thick branches loaded with elongated radial corallites and pointed branch tips, giving this coral a unique and desirable appearance despite its color. By for the most common and most aggressive Acropora found in Tubbataha isAcropora brueggemanni located virtually at every turn from reef flat to lagoons. Color variation for Acropora brueggemanni were a greenish brown or blue, both color variations were encountered living side by side to one another. A purplish colored Acropora granulosa growing in the form of a tabletop from the wall of a ridge. This ridge is located 20 feet from the surface and is part of an underwater canal at least one meter wide. The coral is located 3 feet below the top of the ridge and this placement of the coral only allows it to receive two hours of sunlight a day, the rest of the day it receives ambient light. Interesting to note, the Dive Masters claim that depending on the tide, water flow’s one direction for hours at a time. A beautiful Acropora jacquelineae protecting juvenile fish, and a gorgeous greenAcropora florida with peach colored tips. A very interesting Acropora loripes with cream colored branches and purple tips, living in ten feet of water under super bright sunlight.

Speaking of Acropora, clearly my favorite genus coral, there were several species I encountered that deserve some attention: Acropora abrotanoides a sandalwood colored specimen with thick branches loaded with elongated radial corallites and pointed branch tips, giving this coral a unique and desirable appearance despite its color. By for the most common and most aggressive Acropora found in Tubbataha isAcropora brueggemanni located virtually at every turn from reef flat to lagoons. Color variation for Acropora brueggemanni were a greenish brown or blue, both color variations were encountered living side by side to one another. A purplish colored Acropora granulosa growing in the form of a tabletop from the wall of a ridge. This ridge is located 20 feet from the surface and is part of an underwater canal at least one meter wide. The coral is located 3 feet below the top of the ridge and this placement of the coral only allows it to receive two hours of sunlight a day, the rest of the day it receives ambient light. Interesting to note, the Dive Masters claim that depending on the tide, water flow’s one direction for hours at a time. A beautiful Acropora jacquelineae protecting juvenile fish, and a gorgeous greenAcropora florida with peach colored tips. A very interesting Acropora loripes with cream colored branches and purple tips, living in ten feet of water under super bright sunlight.

Large polyp stony (LPS) corals are as desirable to us in the hobby as are SPS corals. Moreover, to see some of these extraordinary corals in Tubbataha and to witness the size and color of some of these unique corals is truly breath taking. Take for example Lobophyllia hemprichii. While the red or the green colonies of this coral are fairly common, a colony as large as a Volkswagen Beetle has a white outer rim with a mustered colored face and white centers. Galaxea fascicularis is a sweeper tentacle nightmare in captivity, but strangely enough its behavior in the wild is a bit more tolerable. I hypothesize that in captivity we do not keep the animals that keep this coral’s polyps in check. On a coral reef, Butterfly fish and Angelfish keep this coral’s polyps from extending too far. There could well be other critters, but the fact remains the same that this coral will not extend sweeper tentacles in the wild (I never witness sweeper tentacles during the day nor during nighttime dives).

Large polyp stony (LPS) corals are as desirable to us in the hobby as are SPS corals. Moreover, to see some of these extraordinary corals in Tubbataha and to witness the size and color of some of these unique corals is truly breath taking. Take for example Lobophyllia hemprichii. While the red or the green colonies of this coral are fairly common, a colony as large as a Volkswagen Beetle has a white outer rim with a mustered colored face and white centers. Galaxea fascicularis is a sweeper tentacle nightmare in captivity, but strangely enough its behavior in the wild is a bit more tolerable. I hypothesize that in captivity we do not keep the animals that keep this coral’s polyps in check. On a coral reef, Butterfly fish and Angelfish keep this coral’s polyps from extending too far. There could well be other critters, but the fact remains the same that this coral will not extend sweeper tentacles in the wild (I never witness sweeper tentacles during the day nor during nighttime dives).

Coming across a field of brownish white Goniopora columna was a welcome site. In the center of this field was a very large one meter tall red Dendronephthya fully expanded at 1 PM in the afternoon. We visited this site twice in one afternoon each time with different results. On the first visit all the corals were fully expanded and the second time around most of the Goniopora’s had a purple appearance. It turns out that the epidermis of this coral is purple in color, making this area an incredible site to view.

Coming across a field of brownish white Goniopora columna was a welcome site. In the center of this field was a very large one meter tall red Dendronephthya fully expanded at 1 PM in the afternoon. We visited this site twice in one afternoon each time with different results. On the first visit all the corals were fully expanded and the second time around most of the Goniopora’s had a purple appearance. It turns out that the epidermis of this coral is purple in color, making this area an incredible site to view.

A solitary coral that was extremely common in Tubbataha and often misunderstood in captivity is the Plate coral (Fungia). Any Fungia residing or occupying space on rock, rubble or on top of another coral appeared healthy with a well-expanded epidermis, while others discovered on sand beds were deceased or dying. Let me explain the reasons behind this situation– the epidermis of a Fungia coral travels under its heavy skeletal structure. When the skeleton rests on its own epidermis and it is not allowed to breathe, it starts to suffocate under its own weight. In captivity, small specimens will not encounter this issue but as they get larger, it will become more difficult for the epidermis to breathe if situated on fine sand.

One extraordinary fact about Tubbataha Reef is that it is teeming with fish both large and small living alongside one another. Vlamingii tangs (Naso vlamingii) clearly over two feet long as thick as footballs. A small group of Oblique-banded Thicklips (Plectorhinchus lineatus) hovering close to the coral reef, all about 2 feet long. We observed different species of small fish congregating together, assembling large schools, constantly darting in and out of the water column providing us with a kaleidoscope of shape and color. These large schools are formed by different species of Anthias, Damsels, and the occasional yet opportunistic Wrasse all socializing in one large group.

I came across a very exciting situation that everyone on this particular dive missed– the opportunity to observe a cleaning station on a coral reef. From the corner of my eye I saw a full-grown thread fin male Emperor Angelfish (Pomacanthus imperator), this seemed a little out of character for this fish to be out in the open at 12 noon. As I got closer to take photos of this magnificent specimen, I realized that directly behind this fish was a large Clown Triggerfish (Balistoides conspicillum). I then realized that something unusual was taking place and that I should proceed slowly to prevent any possible disruption of this situation. My dive master realized instantaneously what I was trying to accomplish and made adjustments to my gear without hesitation. I rapidly realized that a pair of juvenile Bluestreak Cleaner Wrasse (Labroides dimidiatus) had set up residency under a large Star coral (Diploastrea heliopora) to provide cleaning services. At one point there were seven to ten fish patiently waiting in line to be cleaned by this pair of tenacious Cleaner wrasse. Once on the boat I eagerly displayed the photos on a laptop, and they were all amazed that I was able to capture this incredible event without any disruption to the fish.

I came across a very exciting situation that everyone on this particular dive missed– the opportunity to observe a cleaning station on a coral reef. From the corner of my eye I saw a full-grown thread fin male Emperor Angelfish (Pomacanthus imperator), this seemed a little out of character for this fish to be out in the open at 12 noon. As I got closer to take photos of this magnificent specimen, I realized that directly behind this fish was a large Clown Triggerfish (Balistoides conspicillum). I then realized that something unusual was taking place and that I should proceed slowly to prevent any possible disruption of this situation. My dive master realized instantaneously what I was trying to accomplish and made adjustments to my gear without hesitation. I rapidly realized that a pair of juvenile Bluestreak Cleaner Wrasse (Labroides dimidiatus) had set up residency under a large Star coral (Diploastrea heliopora) to provide cleaning services. At one point there were seven to ten fish patiently waiting in line to be cleaned by this pair of tenacious Cleaner wrasse. Once on the boat I eagerly displayed the photos on a laptop, and they were all amazed that I was able to capture this incredible event without any disruption to the fish.

We had the opportunity to observe a pair of Bluefin Trevally (Caranx melampygus) in the extraordinary pursuit for lunch (to hunt for prey). Circling a small coral ridge in the shape of a pyramid the pair sought their prey with determination on their faces. They circled this coral ridge perimeter several times, one would circle clock wise, the other counter-clock, always intersecting each other’s path. With each repetitive circle, they would increase the velocity of each revolution. Finally, they swiftly headed toward the center of the ridge, creating a cloud of dust two feet high, both retrieving their prey together. This all occurred in the blink of an eye, and from our vantage point we all speculate that this pair must have captured an octopus or a squid that was hiding in the reef. They did not consume their prey at the site, but swam off into the distance holding it firmly in their mouths.

We had the opportunity to observe a pair of Bluefin Trevally (Caranx melampygus) in the extraordinary pursuit for lunch (to hunt for prey). Circling a small coral ridge in the shape of a pyramid the pair sought their prey with determination on their faces. They circled this coral ridge perimeter several times, one would circle clock wise, the other counter-clock, always intersecting each other’s path. With each repetitive circle, they would increase the velocity of each revolution. Finally, they swiftly headed toward the center of the ridge, creating a cloud of dust two feet high, both retrieving their prey together. This all occurred in the blink of an eye, and from our vantage point we all speculate that this pair must have captured an octopus or a squid that was hiding in the reef. They did not consume their prey at the site, but swam off into the distance holding it firmly in their mouths.

A very interesting fish loaded with a ton of curiosity is the Bluestreak Fusilier (Pterocaesio tile). While taking photos of an Acropora landscape, a large aggregation of these Bluestreak Fusiliers approached me cautiously. They circled me once, glanced directly into the underwater housing with curiosity and darted off into the distance, but not before, I got my photo. I refer to these fish as the Neon Tetras of the sea; they get to about 25 cm and move at a rapid pace.

One mid-afternoon one of the Dive Masters suggested we go and watch the pelagic fish at the end of a 40-foot reef flat, which turns into a reef wall down to 300 feet. This particular area opens itself to the vastness of the open sea. However, due to its strong currents, he suggested that we position ourselves at the edge of the flat to observe. This area is well known for its extraordinary congregation of pelagic fish as well as the large fish that like to keep human encounters to a minimum. When we made it to the site, we held on to the rocky edge, laid on the sandy bottom and observed as if we were watching television. Our very own wide screen TV, we spent at least 35 minutes observing and pointing out unusual fish. We did witness large schools of fish such as adult size Yellowfin Tuna (Thunnus albacares), Skipjack Tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis), Indian Mackerel (Rastrelliger kanagurta), and Dolphin fish (Coryphaena hippurus). There was one large fish swimming close to the reef that made a huge impression, a giant Napoleon Wrasse (Cheilinus undulatus) about 5 feet long. On a few occasions, we would glance into the murky water of the open sea and notice some movement. After a few minutes of constant staring that strange movement revealed itself to us, as a large, and thick Blacktip Reef Shark (Carcharhinus melanopterus) about six feet long. It was a very impressive site, this large fish swam 10 to 12 feet above us, I kept thinking how thick it was (so it must not be hungry) as it swam back into the murky open sea.

One mid-afternoon one of the Dive Masters suggested we go and watch the pelagic fish at the end of a 40-foot reef flat, which turns into a reef wall down to 300 feet. This particular area opens itself to the vastness of the open sea. However, due to its strong currents, he suggested that we position ourselves at the edge of the flat to observe. This area is well known for its extraordinary congregation of pelagic fish as well as the large fish that like to keep human encounters to a minimum. When we made it to the site, we held on to the rocky edge, laid on the sandy bottom and observed as if we were watching television. Our very own wide screen TV, we spent at least 35 minutes observing and pointing out unusual fish. We did witness large schools of fish such as adult size Yellowfin Tuna (Thunnus albacares), Skipjack Tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis), Indian Mackerel (Rastrelliger kanagurta), and Dolphin fish (Coryphaena hippurus). There was one large fish swimming close to the reef that made a huge impression, a giant Napoleon Wrasse (Cheilinus undulatus) about 5 feet long. On a few occasions, we would glance into the murky water of the open sea and notice some movement. After a few minutes of constant staring that strange movement revealed itself to us, as a large, and thick Blacktip Reef Shark (Carcharhinus melanopterus) about six feet long. It was a very impressive site, this large fish swam 10 to 12 feet above us, I kept thinking how thick it was (so it must not be hungry) as it swam back into the murky open sea.

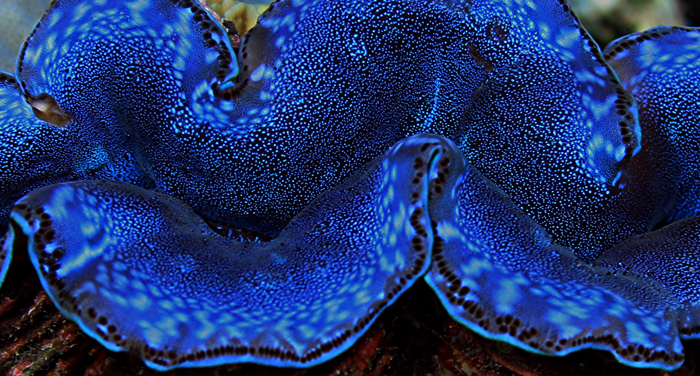

Tridacna clams were virtually at every turn and every depth with all the colors one finds at the local fish store. By far the most common of the species located at Tubbataha Reef was the Tridacna maxima. I located a stunning specimen at about twenty feet and probably the largest I have ever seen (measuring about 45 centimeters), sitting on top of a Brain Coral. When first spotted this clam’s mantel shined a vibrant blue under the intense sunlight, but under closer inspection, it turns out that the mantel is black with millions of iridescent blue spots. Unfortunately for most clams growing on this reef, their lives are short lived. Earlier, I mentioned the fierce competition for space. These clams are quickly over shadowed by their neighbors or are over grown by some type of encrusting coral.

Tridacna clams were virtually at every turn and every depth with all the colors one finds at the local fish store. By far the most common of the species located at Tubbataha Reef was the Tridacna maxima. I located a stunning specimen at about twenty feet and probably the largest I have ever seen (measuring about 45 centimeters), sitting on top of a Brain Coral. When first spotted this clam’s mantel shined a vibrant blue under the intense sunlight, but under closer inspection, it turns out that the mantel is black with millions of iridescent blue spots. Unfortunately for most clams growing on this reef, their lives are short lived. Earlier, I mentioned the fierce competition for space. These clams are quickly over shadowed by their neighbors or are over grown by some type of encrusting coral.

This is one of the largest reefs I have ever visited, with scores of corals fiercely competing for real estate. It is a struggle of life and death, and the coral that can overshadow its neighbor will in essence dominate the reef.

Despite the hectares of rubble this reef once had to endure, and the years of neglect it received, I’m sure many like myself are grateful for the laws put in place in the late 80’s. This reef has made a tremendous recovery.

I can go on continuously raving about Tubbataha Reef like the Australians and share most of my memorable experiences, but that would require taking over this entire issue. I am sure that Josh and Randy have other plans with this issue. Currently I am in the process of arranging a second trip back; with so many hectares, one visit cannot reveal much, but a second trip can uncover opportunities that are even more incredible.

I can go on continuously raving about Tubbataha Reef like the Australians and share most of my memorable experiences, but that would require taking over this entire issue. I am sure that Josh and Randy have other plans with this issue. Currently I am in the process of arranging a second trip back; with so many hectares, one visit cannot reveal much, but a second trip can uncover opportunities that are even more incredible.

0 Comments