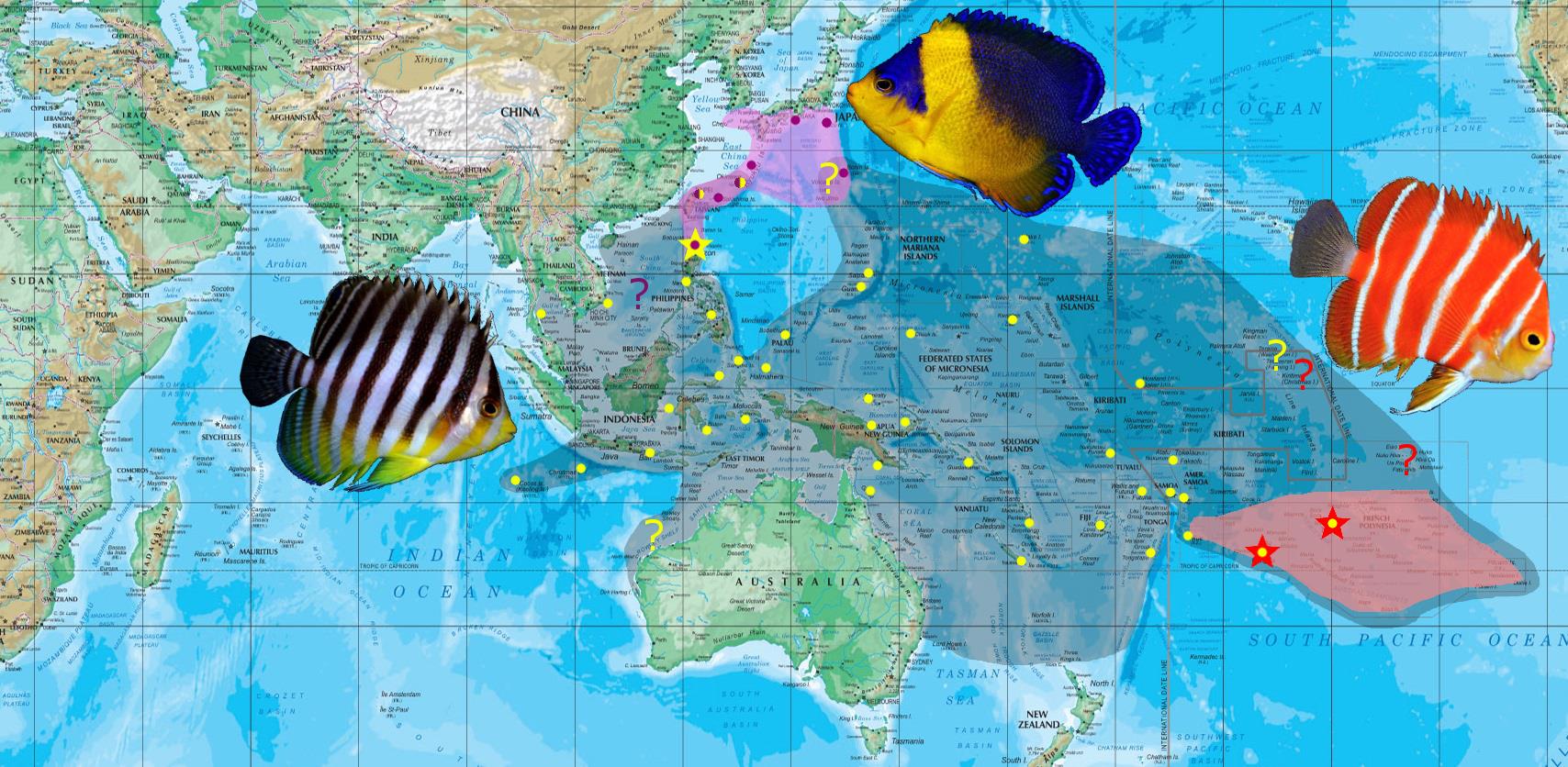

The geographical distribution of P. multifasciata, P. venusta and P. boylei. Map courtesy of Joe Rowlett.

The genus Centropyge is one of seven in the family Pomacanthidae, and comprises of 34 known species distributed in all tropical oceans. This genus is the most species rich of the angelfishes, and attains its maximum diversity in the abundant coral reefs of the Indo-Pacific. Their appearance has earned them the “dwarf angelfish” moniker, which rather aptly describes their small and diminutive stature. Unlike other Pomacanthids, Centropyge are shy, and their taciturn nature often becomes apparent through fleeting glimpses in coral labyrinths or calcareous catacombs. However, despite their coy personalities, most dwarf angelfishes are exuberantly colored and very successful, persisting in habitats ranging from shallow reefs to soul sucking depths in the mesophotic twilight zone.

Unfortunately, the genus has suffered significant discordance in their taxonomy and phylogeny. Most modern classifications of this genus have relied upon morphology, geography and coloration, which have resulted in preliminary erection of various subgeneric classifications. While recent molecular studies seem to support the subgeneric grouping, many conflictions still plague the remaining Centropyge species with respects to the more conventional methods of classification such as coloration and morphology.

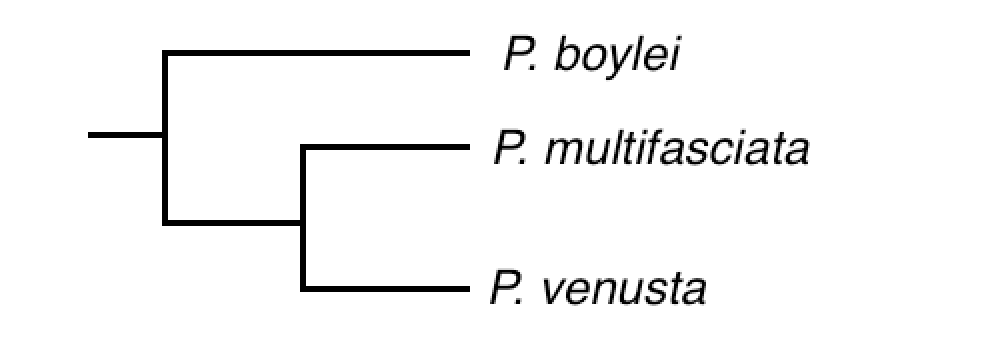

One subgenus proposed in which three species of Centropyge has been translocated into is Paracentropyge. This genus contains three species, all of which are differentiated from the more traditional Centropyge spp. in having a higher body profile and difference in dorsal ray counts. And, much like Centropyge, this group has also been a subject of much taxonomic debate. Although most taxonomists regard Paracentropyge as a subgenus, some authors (Burgess, 1991 and Pyle, 2003) have elevated it to full genus. Molecular studies presented by Gaither; et al shows support in this elevation, and Paracentropyge should, in time, be officially elevated in a thorough review. In this article, we treat Paracentropyge as genus level.

At least one species in Paracentropyge suffers from a more extensive conundrum. P. venusta has, since its discovery in 1969, been shuffled through various genera. Yasuda and Tomiyaga first described it as Holacanthus. It was subsequently moved back and forth between Centropyge and the monotypic Sumireyakko, before eventually being placed in Centropyge. Incidentally, the now defunct genus Sumireyakko is the direct Japanese common name for the species.

The biogeography and evolution of this genus is quite bizarre. P. multifasciata exhibits an extensive geographical distribution across much of the Pacific Ocean, and strays weakly into the Indian Ocean peripheries. The other two species are considerably more restricted, with P. venusta being practically confined to the Japanese archipelago, and P. boylei in extremely deep waters of the French Polynesian Island group. Some inconsistencies in coloration are also noted within this genus. While the striped species are very uniform in their appearance, P. venusta shows extreme volatility in terms of its phenotypic plasticity. This, coupled with its unusual coloration and body pattern, may foreshadow a separate line of evolution that may involve hybrid-derived speciation.

Paracentropyge multifasciata

Paracentropyge multifasciata from Indonesia. Notice the almost complete lack of yellow stripes between the black bands. Photo credit: Lemon TYK.

Paracentropyge multifasciata is an immaculate fish of simplistic beauty. This is the most frequently encountered species both in the field and in the trade, and is immediately identifiable by the 7-8 vertical alternating bands in black and white, giving it its specific name “multifasciata”. These bands transition to a bright lemon yellow towards the ventral region, although this generally varies between individual fish. The bands in the anal fin are always yellow, and so are the pelvic fins. Each dorsal fin spine is tipped with a single cirrhus, and a pair is likewise present on the tip of each pelvic fin. The caudal fin is hyaline with a series of black spots. Juveniles are more sparsely banded, and possess an ocellus on the soft dorsal fin, which becomes noticeably less apparent with age. The bands fill in with age, and the ocellus either completely disappears or is reduced to a vestigial remnant.

P. multifasciata from the Marshall Islands. Notice the clearly visible yellow stripes in-between the black bands. Also notice the prominent dorsal fin cirrhi. Photo credit: Lemon TYK.

This species is rather consistent in its appearance and does not appear to exhibit any geographical variation throughout its range. It does, however, possess thin yellow stripes between the black bars, and this feature appears to show inconsistent variation amongst individuals, ranging from nascent to highly noticeable. It has been suggested that the presence or absence of these stripes correlate to distinct geographical variants, but in examining numerous specimens from across the board, we find evidence to suggest against this.

C. multifasciata is bashful by nature, and is frequently found in dense calcareous catacombs in depths between 30-300ft. It prefers lurking in the shadows of complex reef matrices, where it swims upside down or sideways away from the prying eyes of divers. Because of its cryptic and highly evasive nature, this species is not easily caught without the use of drugs. It appears quite frequently in rotenone stations.

Paracentropyge multifasciata exhibiting its typical swimming behavior in Bali. Photo credit: Vincent Chalias.

Despite its intractable nature, this species exhibits an incredibly wide geographical distribution. It is found throughout the Indo-west Pacific, from the Ryukyus Arc south to the Philippines and Indonesia. It is also present in the Marianas, Micronesia, Papua New Guinea, Coral Sea, all of Melanesia and parts of the French Polynesia. It strays weakly into the eastern peripheries of the Indian Ocean, namely Cocos Keeling and the Christmas Island.

Its wide distribution puts this species in close sympatry with the other two Paracentropyge members, where it is confirmed to hybridize with at least one. Because of its highly secretive and sensitive nature, this species often succumbs to collection and shipping stress. It has a dismal survival rate in captivity, but specimens coming out of Micronesia and the Coral Sea tend to adapt better. Like many delicate species, a short supply chain coupled with drug free collection methods can significantly improve the chances of survival.

Paracentropyge boylei

Paracentropyge boylei. An aquarium specimen in Japan. This individual was collected from the Cook Islands. Photo credit: Lemon TYK.

This extravagant species of immaculate opulence has long been regarded as one of the greatest living treasures of the angelfish family. Despite its recent meteoric debut in the mainstream aquarium trade, its status as an iconic book fish has hardly been relinquished. Familiarity has not made us jaded with the clinquant beauty of this magnificent species, and its increased presence in the industry only serves to remind us why this species is truly the crème de la crème of Pomacanthids, deserving of a place in the pantheon of reef fish pop culture.

In Paracentropyge boylei, the ground coloration is livid scarlet, superimposed with five roughly vertical stripes in chantilly white. The operculum and pelvic regions are tangerine to yellow, and a single white stripe runs in-between the eyes from the nape through to the mouth. The pelvic fins are ferruginous, and bordered copiously in white on the outer rays before trailing off in a pair of cirrhi. A cirrhus is also present on the tip of each dorsal fin spine, but these are never quite as long or developed as with P. multifasciata. The caudal fin is hyaline and unmarked. Because of its festive coloration, this species has been aptly coined with the colloquial name “Peppermint Angelfish”.

P. boylei from Moorea in captivity. Notice the presence of dorsal and pelvic fin cirrhi. Photo credit: Lemon TYK.

Paracentropyge boylei from Moorea. Notice the extensive development of the pelvic fin cirrhi here. Photo credit: Lemon TYK.

Like P. multifasciata, this species is extremely cryptic and shy, preferring to skulk within complex reef labyrinths. It is essentially identical to the preceding species, but has adapted to living in very deep reefs well into the mesophotic twilight zone. This habitat preference has catalyzed unique evolutionary traits, one of which being its striking red coloration. Red is the first wavelength in the visible spectrum to be absorbed by water, and starts disappearing at 15ft. In deep water, red completely disappears, appearing black instead, allowing this species to appear incognito amongst the shadows.

C. boylei is restricted to the French Polynesia in very deep waters. For years, this species was known only from its type locality — Rarotonga, Cook Islands. In 2012, a group was filmed for the first time in the reefs of Moorea at a depth of 360ft. This represented a new 700-mile range extension for the species since its initial discovery, but it’s likely that P. boylei is more widespread in the French Polynesia than currently known. The Peppermint Angelfish is found in depths starting at 200ft, but becomes significantly more abundant at 400-450ft.

Interestingly, the very closely related P. multifasciata is sympatric throughout its entire distribution, but because of their difference in depth preference, both species rarely mix. Rufus Kimura has reported seeing both species swimming together at 350ft in Moorea, which is right at depth limit at which P. multifasciata occurs. This difference in habitat preference has allowed two highly similar species with near identical biological and ecological needs to share the same sympatric range without directly competing with each other. The phenotypic differences in color also correlates to the evolutionary advancement of P. boylei into deeper waters. However, whether or not the two species mix in the narrow contact zone is unclear. No hybrids have been documented so far.

Paracentropyge venusta

Paracentropyge venusta is the unusual oddity of the genus, displaying a body pattern quite unlike the preceding two species. The epithet “venusta” comes from the latin word Venus (“the goddess of love”), who was allegedly attractive. Indeed, P. venusta is a striking combination of cobalt blue and chrome yellow.

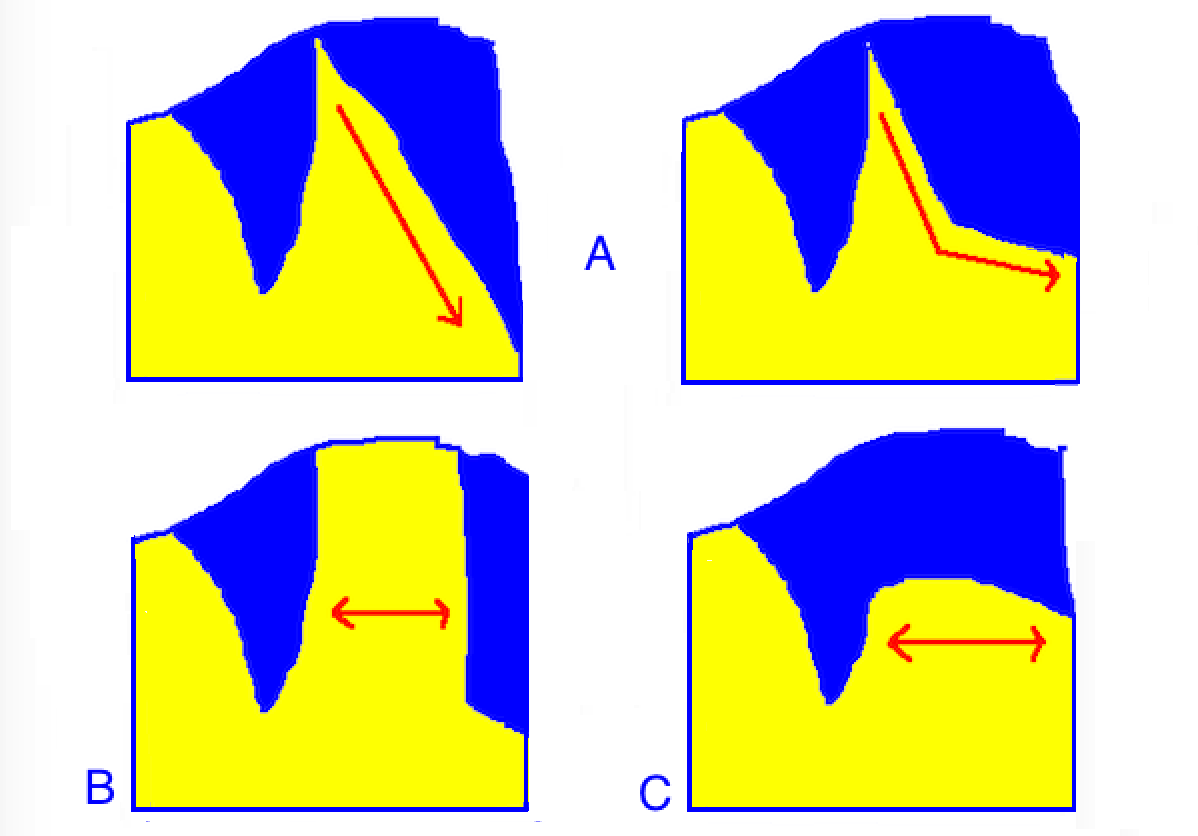

All specimens possess a crown on the nape, which travels at an oblique angle to the base of the pectoral fin base, partially concealing the eye in a triangular facemask. Like P. multifasciata and P. boylei, P. venusta has cirrhi on all its dorsal fin spines as well as pelvic fin tips. The caudal fin is opaque cobalt with a series of hieroglyphic scrawling in iridescent blue. The species lacks the usual vertical banding, but instead, adopts a roughly bicolor appearance with no significant body markings. Its appearance is extremely plastic, and spans a veritable plethora of variations. Despite the phenotypic volatility, the variability is determined by two major factors. 1) The crown marking immediately posterior to the triangular facemask. 2) The amount of yellow or blue present throughout the fish.

In examining this species, three major crown variations can be deduced. These are illustrated above in a very rudimentary sketch, and below with photographic examples.

In type A variants, the blue facemask is separated from the rest of the body by a diagonally oblique yellow wedge. This wedge is an extension of the yellow anterior body, and delimits the mask from the dorsum on the distal edge in a smooth oblique sash. As the fish matures into the adult stage, the oblique delimitation makes a gradual horizontal bend to the posterior anal fin.

In type B variants, the yellow wedge separating the mask from the dorsum is widened, such that the two blue portions never meet. The wedge takes on a more rectangular appearance. Like type A variants, the yellow limit distal to the crown makes an unbroken oblique line to the anterior anal fin in juveniles, or a horizontal bend to the posterior anal fin in adults.

Type C variants are essentially the reverse of the former. Here, the mask touches the blue dorsum to form a continuous ridge. The yellow wedge is reduced inferiorly, and in extreme cases can be totally absent.

In addition, all specimens are subjected to variations even within their arbitrary designated types. The amount of blue and yellow also differ rather drastically, and can change as the fish age and matures in captivity.

Paracentropyge venusta exhibiting a type B crown. Notice the abrupt vertical bend in the yellow delimitation opposite to the crown. Photo credit: Lemon TYK.

Paracentropyge venusta with a dubious and aberrant crown marking. Here it appears to be an intermediate phenotype between types A and C. Notice the iridescent scrawling on the edge of the dorsal, anal and caudal fin. Photo credit: Ameblo.

A pair of P. venusta with type C crowns. Notice the vertical separation between the blue and yellow portions of the body, giving the fish an almost equal bicolored appearance. Photo credit: Yakushima Diving Life.

Another individual with a high amount of blue body coloration. Notice the near absence of the yellow crown wedge. Photo credit: Tetsu.

Take note of the irregular separation of blue and yellow body colors in this adult specimen. Photo credit: Tetsu.

Take note of the exaggerated oblique separation in body colors in this young specimen. As it ages, the oblique sash will gradually straighten horizontally. Photo credit: Kushimoto-sakana.

Aberrant “high-yellow” P. venusta with a vestigial facial mask and crown markings. Photo credit: Tarafuku.

Two examples of P. venusta exhibiting crown aberrations. Notice the irregular color separation in the individual within the subset photo. Photo credit: Centropyge Log Blog and BlueHarbor.

On top of the wide intraspecific variation, Paracentropyge venusta is not uncommonly found to exhibit extreme phenotypic aberrations. Specimens with “high-yellow” coloration are infrequently documented, and these often sport a highly irregular reduction of the corresponding blue body pattern. In addition, the facial mask is also often reduced to a vestigial smudge. It would seem like these individuals sporting such aberrations are unable to fully express the blue coloration, but curiously, they have been shown to fully revert to the standard wild type template design back in captivity. What causes this is not yet fully understood, but it draws similarities to specific piebald or vitiligo aberrations in other Centropyge spp, which over time have shown to also revert back to wild type phenotype in captive care.

Whether or not a dietary or environmental stimulus in the wild is causing this is, again, not quite certain. But it does add another dimension to the polychromatic volatility of this species. It is also curious to note that Paracentropyge venusta is largely restricted to the Japanese archipelago. It ranges from Japan, south to the Ryukyu Arc and the northern extension of the Philippines. It is also documented in Ogasawara just north of the Mariana Arc. Vagrant strays have been found in Palau (R. Myers pers. Comm. 2009), but there is nothing to suggest a resident population there. P. venusta otherwise prefers the same habitat as the preceding two species.

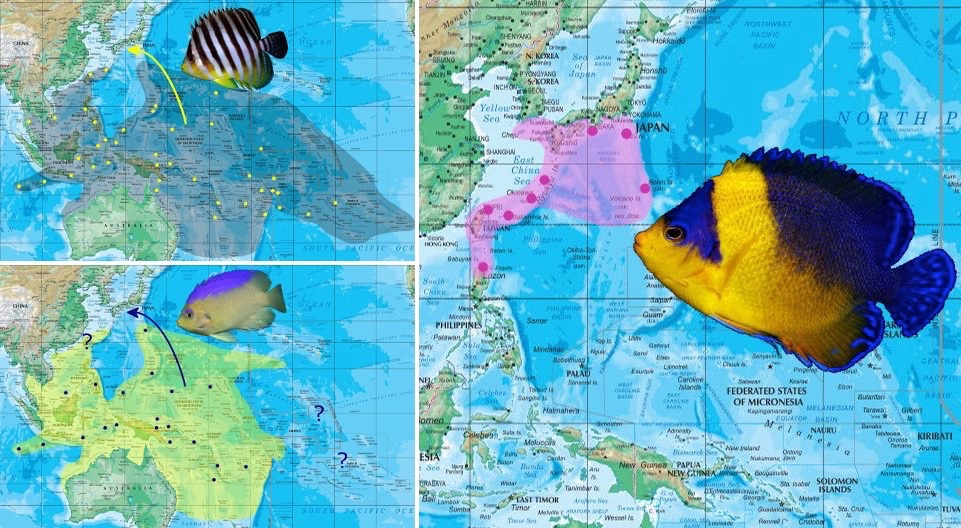

Could P. venusta have risen from the hybridization of ancestral populations of P. multifasciata and C. colini? Map courtesy of Joe Rowlett.

As suggested to me by Joe Rowlett, the restricted distribution of P. venusta fills a void in the biogeographies of two phenotypically similar species (Paracentropyge multifasciata and Centropyge colini), suggesting that this Japanese endemic may ultimately derive from an ancient hybrid population. This might come across as highly contentious, but could the unusual biogeography and phenotypic plasticity of P. venusta account for it being hybrid derived? Again, this phenomenon is repeatedly seen in a few other species, such as Centropyge shepardi, Cirrhilabrus katherinae and Chaetodon flavocoronatus.

It would seem plausible that both P. multifasciata and C. colini could occur as great rarities in the Ryukyu Arc, catalyzing the formation of hybrids. While the two species may not necessarily produce P. venusta as an F1 hybrid, it would seem possible that their direct ancestors millions of years ago might produce a precursor, which through reproductive isolation in the Japanese and Ryukyu archipelago, eventually speciated into what we know today as Paracentropyge venusta.

An aberrant C. colini with an unusually extensive mask. Compare this with P. venusta below. Could this suggest an ancient relationship? Photo credit: RVS FishWorld and Ceppo.

Centropyge colini, with its blue back and yellow body, resembles quite closely to that of Paracentropyge venusta. In the aberrant example of C. colini above, the fish possesses a vestigial facemask, a trait not normally present in this species. Could this indicate an ancient relationship with P. venusta? Again, as contentious as this might seem, the similarities in phenotype and aberrant biogeography seems to suggest that this might not be all that implausible. However, until extensive genetic testing is carried out on this species, this hypothesis should not be taken too literally.

Hybrids

Paracentropyge venusta x P. multifasciata in captivity. Photo taken in 2015. Photo credit: Lemon TYK.

The same individual above photographed in 2008, 7 years ago. Notice how the stripes have changed. Photo credit: Glassbox-design.

At least one hybrid has been reliably documented in this genus, and that is between Paracentropyge venusta and P. multifasciata in the Northern Philippines. Here, P. venusta is at its distribution limit, and puts it in close contact with P. multifasciata. Amazingly, the infusion of P. venusta blood with P. multifasciata produces an offspring with highly convoluted, maze like markings. What’s interesting is that like P. venusta, the body pattern is rather volatile, appearing to mosaic about as the fish ages.

The two photographs above are of the same fish, taken seven years apart in 2008 and 2015. Notice how the striations have both ligated and re-anastomosed along the dorsum and soft dorsal fin. This could be attributed to P. venusta, which likewise appears to show minor phenotype shift as it ages. This hybrid is exceedingly rare, and has been documented only a handful of times. In the aquarium trade, no more than five individuals have been offered, where they retail for ridiculously exorbitant prices.

The sympatric overlay with P. multifasciata and the other two species occur at the polar ends of its distribution. Although P. multifasciata overlaps with P. boylei in their range, they only narrowly mix in a contact zone of about 300ft, where both species are at the limits of their preferred depth zones. Therefore although unlikely, the hybridization between the two cannot be discounted.

Despite the seemingly small and uncomplicated nature of this genus, much is still left unanswered, especially with regards to the evolution of P. venusta. P. multifasciata and P. boylei display an evolutionary divergence with regards to their specific niche preference, coupled with phenotypic adaptation to the different habitats. As mentioned in the foreword, the taxonomic placement of this group should follow a full generic upgrade pending a formal review. Hopefully, the mysteries surrounding P. venusta would be elucidated in time to come.

Acknowledgements:

The discussion of hybrid speciation in this article is credited to the research of Joe Rowlett, who has also so kindly helped in the making of the distribution maps. Thanks also to Dr. Richard Pyle and Rufus Kimura for sharing their valuable observations on the distribution and behavior of Paracentropyge multifasciata and P. boylei. This article would not have come to fruition without the much appreciated help of the aforementioned people.

References:

M.R Gaither et al. 2014. Evolution of pygmy angelfishes: Recent divergences, introgression, and the usefulness of color in taxonomy. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution 74 (2014) 38-47.

0 Comments