Sea anemones pose many challenges for the home aquarist. Some (e.g. Radianthus magnifica) require exceptionally high light and water flow to thrive. Others (e.g. Exaiptasia pallida & Anemonia spp.) are notorious pests, growing where they are not welcome. And nearly all have the frustrating habit of wandering about the aquarium, usually resulting in a macerated anemone-soup whenever there is a powerhead present. One of the worst choices for the home aquarist is Actinostephanus haeckeli, known variably as the “Snake Sea Anemone” or “Haeckel’s Sea Anemone”.

The scientific name derives from the Greek for “radiating crown”, with the species named in honor of famed 19th-century zoologist and illustrator Ernst Haeckel. It belongs to a small family (Actinodendridae) which is easily recognizable by having branched or vesicular tentacles, as well as the burrowing habits of most species. Actinodendrids are morphologically adapted to their ecological niche, having a reduced pedal disc (i.e. the “foot”) and a corresponding loss of the basilar muscles which allow for the typical gliding movement of sea anemones.

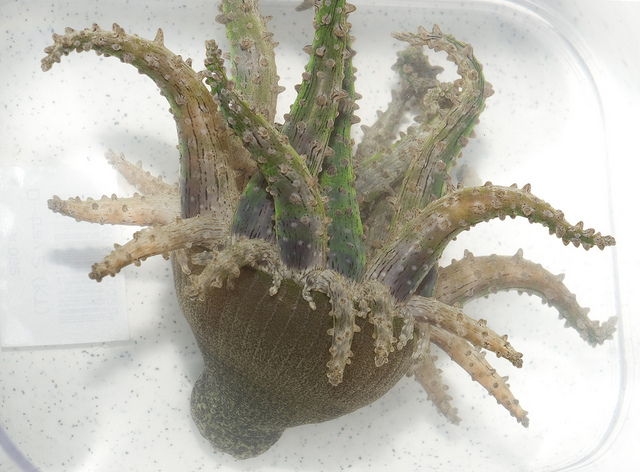

Actinostephanus has only one recognized species and can be easily identified by the small protuberances (=vesicles) which poke out at random along the tentacles (branched in related groups). The oral disc is highly variable in coloration but usually shows some indication of twelve bands emanating out from the stomodaeum (i.e. the “mouth”). These bands correspond to the twelve large tentacles of this beast, while the spaces between each yield a slightly smaller tentacle, resulting in 24 total. The maximum size is not well-documented; aquarium specimens are usually 6-10 inches across the full tentacular diameter. Colors vary from black to brown to green, often showing attractive stripes and bands, as well as contrasting tentacular vesicles.

The other two genera in this group—Actinodendron & Megalactis, the “Hell’s Fire Sea Anemones”—are well-known for the potency of their stings, and the same is true for Actinostephanus. I can find little medical data on just how damaging a sting is from these creatures, but anecdotal reports suggest they can leave lasting scars and cause severe pain. Kevin Kohen of LiveAquaria compared the feeling to having a broken arm, with unsightly red blisters to go along with the pain. Which begs the questions, why are these being made available to home aquarists?

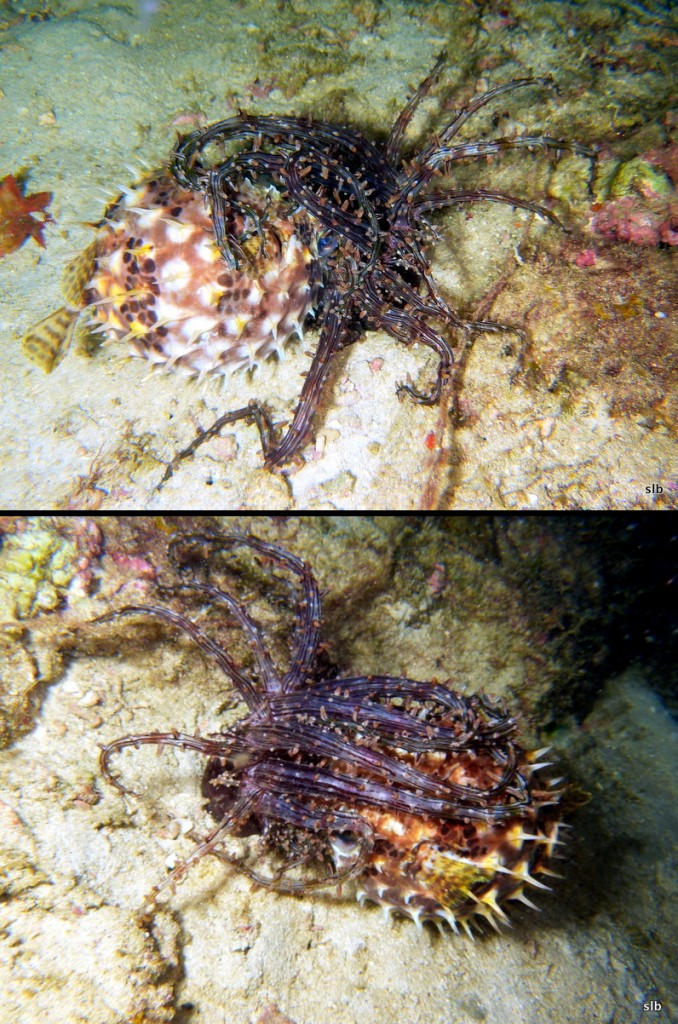

Strike two against Actinostephanus is its general unsuitability for being housed alongside other animals in an aquarium. Judging from photographs, this species seems to be a specialist at snaring fish with its sticky tentacles. The video below and the photos above give an idea of just how effective it is at this. This means that any fish kept with this species is likely to eventually be stung or eaten, the same holds true for things like snails and sea stars. There’s little information concerning whether they can damage corals, though they may at least be safe with soft corals.

In the wild, this species occurs in sandy lagoons buried up to its oral disc. They may be more nocturnally active, though this doesn’t seem to be the case in captivity. I’ve dealt with Actinostephanus only once, and it scared me more than any venomous fish ever has. We humans are maladroit, graceless buffoons when we stick our arms into an aquarium, and attempting to scrub algae around such a dangerous creature is a recipe for disaster. Actinostephanus can generally be coaxed with some gentle prodding into closing up, but often they leave just enough of themselves poking out to keep one on their toes. What’s more, they have a tendency to shed mucous, along with unfired nematocysts, into the water when disturbed. While I have never felt the full fury of their sting, I did have the misfortune of running my hand through some nematocyst-laden water. It was unpleasant… for quite some time.

If there is a role for Actinostephanus to play in the aquarium hobby, it is as a unique species for a small biotope focused on sandy lagoons. Fish are necessarily avoided, but a variety of crustaceans, like the “Sexy Shrimp” Thor amboinensis or the “Magnificent Anemone Shrimp” Anclyomenes magnificus, as well as the “Harlequin Crab” Lissocarcinus laevis, are common associates in the wild, managing to clamber about the gauntlet of tentacles without harm. Actinostephanus is a fascinating species with a unique beauty, but it is definitely best avoided by all but the most dedicated aquarists.

I have no idea how one started growing in my tank. I have a green one that looks just like that on my substrate the size of a penny. Should I get rid of it?

Do they multiple fast? Will it eat my fish or shrimps? (I do have a small sexy shrimp that lives pretty close to this thing)

Thanks