By Richard Aspinall

We all know by now that the underwater world is replete with amazing and astounding creatures, many are well known through decades of research and are accessible to anyone interested through public and private aquaria. It’s also the case that a good chunk of species on the planet have life histories that in many cases are still being uncovered and when they are being studied, the results throw up more questions than they do answers, such is the way of scientific enquiry. For those of us who are not existing at the cutting edge of biological research and have more of a hobbyist, though still passionate, interest in the underwater world, there has never been a better time to understand the lives of marine creatures. Whilst many folks keep interesting species in captivity, increasingly hobbyists are seeking to understand more about marine species in the wild and this must be applauded and encouraged.

In this article I’m going to be raiding my image archive and sharing a few pictures to talk about some of the wonderful techniques that have evolved in fish to help them survive. Firstly, let’s look at camouflage.

Sometimes hiding in plain sight is the safest way to go. Illustration by J.R. Zuckerberg.

Camouflage is very common in the natural world and for good reason; you’re born with it and it takes little energy to operate. The more closely you resemble your surroundings the less likely you are to get eaten and conversely the more likely you are to be able to sneak up on your prey, with the same result; you survive and pass on your genes to your progeny. Not all fish rely on camouflage, some rely on warning colours to advertise their unpalatability, some are simply too big to need it (in their adult phase at least) and others rely on entirely different techniques to dupe their fellows, but let’s look at a few examples where blending in has worked very well.

If your evolution has lead you down the road of living life on the substrate, you’re going to want to resemble the rock, sand or whatever the sea floor offers, and there’s no finer exponent of this lifestyle than the flatfishes of the Soleidae and some related genera (forgive me as this is not an article that will look at detailed taxonomy). Members of the Soleidae, are distinctively flattened with a fascinating anatomy that morphs a ‘normal’ looking fry into a fish with one eye that has ‘migrated’ almost ninety degrees – fascinating stuff. They tend to be slow swimmers and rely on their complicated colouration, patternation and in some cases the ability to vary their pigmentation to blend in further.

Yep, there’s a fish here. This fish which I believe to be Bothus podas, is wonderfully camouflaged and also partly buries itself in the substrate. I only noticed it when I was photographing a fish a few inches away.

Bothus pantherinus – this fish was disturbed and hasn’t had chance to rebury itself. Note how they eyes are raised to keep them above the substrate.

Cryptic colouration is not limited to the flatfishes of course, but before we leave them I wanted to share an interesting little fish from the Soleichthys family. S. heterorhinos has employed a different strategy and has evolved, presumably from a camouflage patternation, to a pattern and colouration that resembles a toxic flatworm and by doing so is relying on predators to leave it alone, even though one assumes it is as tasty as its kin.

The Banded Sole (S. heterorhinos) grows to around four inches long, is in my experience nocturnal and even moves with a rippling action across the sea floor similar to that of the flatworms it mimics. There are a number of flatworms that the sole resembles, this species is Pseudobiceros fulgor. Both species are from the Indo-Pacific.

We’ll return to mimicry later, but first let’s return to other species of interest that are recognised masters of deception, if you’ll pardon the pun. Many divers and aquarists are justifiably fascinated by Frog fishes of the Antennariidae, and rightly so! These are astoundingly coloured, patterned and textured fish that so closely resemble soft corals, sponges or algae covered rockwork that they can go utterly unnoticed by folks with cameras and of course the fish that they ambush and engulf with their cavernous mouths. Several writers have chronicled how some species of frogfish will change their colouration to blend in to new surroundings in aquarium life or indeed new areas in the wild.

It took me ages to spot this fish on a shipwreck in the Indian Ocean and I could not work out what my buddy was pointing at until it moved. The fish is doing a wonderful job of blending into the coralline algae and rust pattern on the wreck. Its various skin folds and flaps resemble small algal growth, hydroids and similar.

Another of my favourite fish that is a regular feature of many a shipwreck, hence why divers see them, is the Crocodile Fish. This species (Papillocauliceps longiceps) from the Indian Ocean reaches three feet in length and is once more superbly coloured. I have many images of them from night dives on ship wrecks, where they often sit on deck plates and spars making photography far easier. Again it is an ambush predator and unlike frogfish, is not, I would suggest, a good aquarium animal.

This fish was photographed on a famous wreck in the Red Sea, keen eyed readers will note the rear of a railway carriage (a water tanker) behind the fish.

Another fish, this time on a sandy bottom. Note the frills which have evolved to camouflage the eyes.

Camouflage works then by breaking up the animal’s outline, hiding it entirely and ensuring predators pass by or in many cases prey comes close. Of the latter we see many fish that have evolved a sedentary lifestyle with cryptic colouration and large mouths to engulf prey.

Scorpaenopsis diabolus – the aptly named Devil Scorpionfish.

Scorpaenopsis oxycephala blending into a reef.

Triptoterygion melanurus minor – for a small fish at risk from predators, camouflage is a ‘no brainer.’

Or… go a different way and blend in by going see-through. These tiny gobies (Bryaninops natans) reach around an inch in length and hide within coral branches.

Blending in isn’t just limited to rock and other non-living substances. Many fish have evolved to closely resemble living structures and in some cases are then entirely dependent upon their habitats, my favourite example of this, and a common aquarium fish, is the Long-nose Hawkfish. Oxycirrhites typus might at fist appear oddly patterned, what use could a red check pattern serve? Only when you see the fish in its natural habitat, where it rests in sea fans do you realise why.

O. typus – lives in a net-like animal and has net-like camouflage. Like all Hawkfish it darts out from its resting place to snatch prey items from the water.

The utterly charming Arothron diadematus at night, doing its best to resemble a sponge perhaps? I understand this Indo-Pacific fish has been released into waters around Florida.

The corallivorous Leopard Blenny (Exallias brevis) lives amongst the branches of hard corals and has quite a generic patternation.

Blending in often requires fish to not only evolve colouration, patternation and of course overall body plans but also requires the evolution of certain behaviour. Many well-camouflaged fish will swim and move to better resemble their habitats. I particularly enjoy the filefish family for this behaviour, which they will adopt in captivity if suitable structures are provided (living or artificial). This behaviour does make them hard to photograph though and I spent a long while, waiting for this file fish (which I think is Monacanthus tuckeri) to emerge from the sea whips and gorgonians.

This file fish adopts a head down posture and camouflage.

The colouration and fin structure of the Banggai Cardinal makes more sense when you see it sheltering in the long spines of an urchin.

This fish (Aulostomus maculatus) relies on head down posture, colouration and body movements to hide from predators and from prey.

There is of course an even simpler method involving the use of colour to keep yourself invisible – be as dark as possible. But this isn’t that obvious to us animals that live with our ‘normal’ light spectrum. We all know how the longer wavelength red end of the spectrum is noticeably reduced in sea water, with the effect increasing with depth, which goes a long way to explain why many deep water species appear red under full spectrum lighting. Take the image below for example, rich colours of yellow, pink and red. Well ‘yes’ under my flash guns, but this image was taken inside a ship wreck where the limited light available would render the fish very dark indeed.

Large eyes hint at low light lives in nocturnal fish.

More ‘red’ soldierfish (Myripristis murdjan) in their natural daytime haunt of a cave. They hunt on the reef at night.

Some fish of course use their colouration to mark themselves out in other ways and things here get a little more complicated. Some fish that would ordinarily be ideal prey items are ignored by predators and are given unique ‘access all areas’ status. I’m talking of course of the cleaner wrasses that are so noticeable on the reef, using their stripe and white/blue colours (very visible in the shifted undersea spectrum) to advertise their services in order to earn them a living. Cleaners also use a distinctive swimming style to further mark themselves out.

Cleaner wrasse (Labroides dimidiatus) are highly visible underwater and recognised as more useful alive than dead by predators.

Elacatinus evelynae, now available as a captive bred fish uses the same strategy as L. dimidiatus and is a far better fish for aquarium life.

Stripes don’t always mean usefulness, the false cleaner wrasse (Aspidontus taeniatus) is a great example of mimicry. It pretends to be a ‘true’ cleaner wrasse but will nip chunks out of the fins of fish it is cleaning. It has been put forward that adopting the colours of L. dimidiatus affords protection from predation first, as analysis of stomach contents shows that the fish rely on ‘cleaning’ less than other food sources.

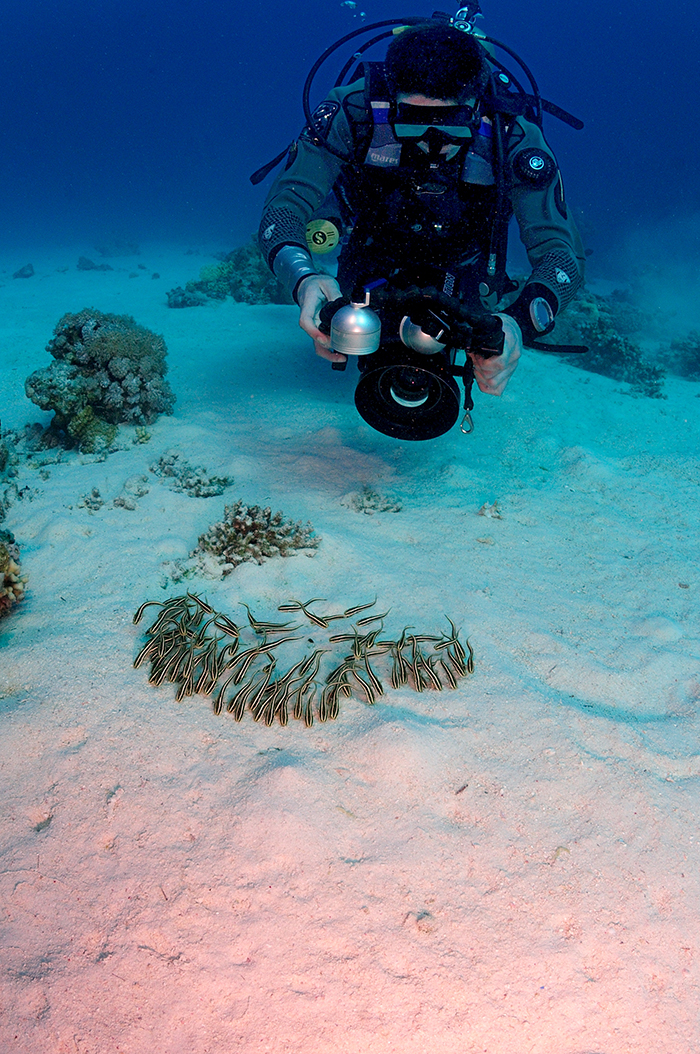

In some instances, stripes may advertise that fish are toxic. Analogous perhaps to the warning stripes found on many venomous insects on land. Take Striped Eel Catfish (Plotosus lineatus) for example. These fish that move as one, in their juvenile phase, across the sea floor have pronounced black and white stripes and it has been suggested this advertises their venomous nature. Some eels will mimic sea snakes to steal some of their thunder.

Shoaling fish rely on one of the most straightforward methods of hiding in plain sight – safety in numbers. There is no finer sight underwater than watching large shoals of silversides or similar ‘bait’ fish moving in a seemingly orchestrated pattern, using their silver colouration to reflect sunlight and to confuse predators so that an individual fish’s chance of survival is massively increased. We see this behaviour in fish across the planet and across the fish families and it is sadly behaviour that outside of a few species of Apogonidae that we are unlikely to see in home aquaria.

Shoaling fish rely on one of the most straightforward methods of hiding in plain sight – safety in numbers. There is no finer sight underwater than watching large shoals of silversides or similar ‘bait’ fish moving in a seemingly orchestrated pattern, using their silver colouration to reflect sunlight and to confuse predators so that an individual fish’s chance of survival is massively increased. We see this behaviour in fish across the planet and across the fish families and it is sadly behaviour that outside of a few species of Apogonidae that we are unlikely to see in home aquaria.

Shoaling Chromis and below, Anthias. Such close living often involves haremic lifestyles and ‘pecking orders’ that make replication of the behaviour in captivity difficult to achieve and perhaps attempting to do so is in some cases unethical.

Clearly ever fish has its own strategies to survive, find food, evade predators and pass on its genes and it’s either a fantastic illustration of Darwin’s theories or the signature of a very, very clever Creator. I prefer the former explanation but I don’t wish to offend anyone who prefers to see a Creator’s guiding hand.

Clearly ever fish has its own strategies to survive, find food, evade predators and pass on its genes and it’s either a fantastic illustration of Darwin’s theories or the signature of a very, very clever Creator. I prefer the former explanation but I don’t wish to offend anyone who prefers to see a Creator’s guiding hand.

My next series of examples are some of the best in the natural world, eyespots! Eyespots, or ocelli (ocellus is the singular) are commonplace and are, above the surface best seen in butterflies and moths that use them to scare away predators. Think of those large tropical moths with eye spots on either wing that will scare a predator into thinking ‘owl’ and hopefully scurrying off.

In fish, eye spots serve to scare away predators and to act as diversions from the real eye and that ever-so-valuable head end and in some fish I’d argue they do a little of both. Let’s look at some fish that employ ocelli to distract and confuse attackers.

White Banded Possum Wrasse (Wetmorella albofasciata). Many wrasses have ocelli.

Many species of wrasse, including the huge Napoleon wrasse (when a juvenile) employ eyespots on their rear fins (or rear of their dorsals). The ocelli are located on non-critical parts of anatomy so if an attacker – and predators do seem to ‘home in’ one eyes – goes for that area the fish is likely to swim away with less than fatal damage. It will pass on its genes and over time, assuming similar incidents happen to other fish, the species as whole retains or improves their ocelli.

One of the best ‘eyed’ fish is the Foureye Butterfly (Chaetodon capistratus). The fish has large and prominent eye spots close to the caudal fin and a dark band that obscures its real eye, serving to confuse predators as to the fishes’ likely direction of escape and thus making attacks less successful. We can assume that the same outcome is likely in many instances where fish have ocelli, as with the wrasse example above. The ocelli serve several purposes perhaps, depending on the attacker. I assume that it is also likely that large ocelli might confuse predators into thinking they are dealing with a much larger and potentially more challenging prey item.

One of the best ‘eyed’ fish is the Foureye Butterfly (Chaetodon capistratus). The fish has large and prominent eye spots close to the caudal fin and a dark band that obscures its real eye, serving to confuse predators as to the fishes’ likely direction of escape and thus making attacks less successful. We can assume that the same outcome is likely in many instances where fish have ocelli, as with the wrasse example above. The ocelli serve several purposes perhaps, depending on the attacker. I assume that it is also likely that large ocelli might confuse predators into thinking they are dealing with a much larger and potentially more challenging prey item.

Chelmon rostratus ‘uses’ an identical approach.

Another group of prominently eyed fish are the Centropyge angels – many of the fish have ocelli, but in their juvenile phases, presumably as they mature the ocelli become less valuable, however I’m no ichthyologist and I’d be fascinated to hear if anyone has any more knowledge than I on why the adult fish lose their eye spots.

So, why does this matter to aquarists? Well, I hope it would matter to anyone interested in fish, to know a little more about their biology and life histories. I’ve always felt knowledge for its own sake is valuable, but in some cases looking beyond the ‘pretty colours and patterns’ helps hobbyists to anticipate the needs of their fish a little better perhaps?

I hope I have, in a small way, encouraged you to think a little deeper about your fish in this admittedly very limited scratching of the surface.

The other option of course is just to find a hole and hide!

0 Comments