A spotted foxface has spotted an unspotted foxface here at Romblom in the Philippines. Credit: Three P Holiday & Dive Resort

This might be unfair, but, from what I’ve gathered, there are very few aquarists who get excited by the Foxface Rabbitfish. Despite its bright, cheery colors and interesting pattern, it seems the main reason these get purchased is to control nuisance algae (though, rather ironically, they are really only good for controlling bubble algae… but, I digress). Who out there has grabbed a foxface out of pure, unadulterated love for Siganus vulpinus? Who out there is keeping this fish in a mated pair, as they are normally found in the wild? Pity the poor, lonely foxface swimming about in solitude. Today, I’d like to show a little appreciation for this humble fish and discuss its intriguing evolutionary history.

You’ll often see the Foxface, along with the rest of its kin, classified separately into the subgenus Lo, based on the elongation of the face found in this species group. But genetic study has resoundedly disputed this, showing quite conclusively that this lineage is actually derived from well within the genus Siganus. Their unusually attenuated shnoz is even found, albeit to a lesser extent, in another common aquarium species, the Coral Rabbitfish (S. corallinus), having independently evolved for the same algae-plucking task.

The illustrious, resplendent, superlative S. magnificus, from the Surin Islands, Thailand. Credit: takau99

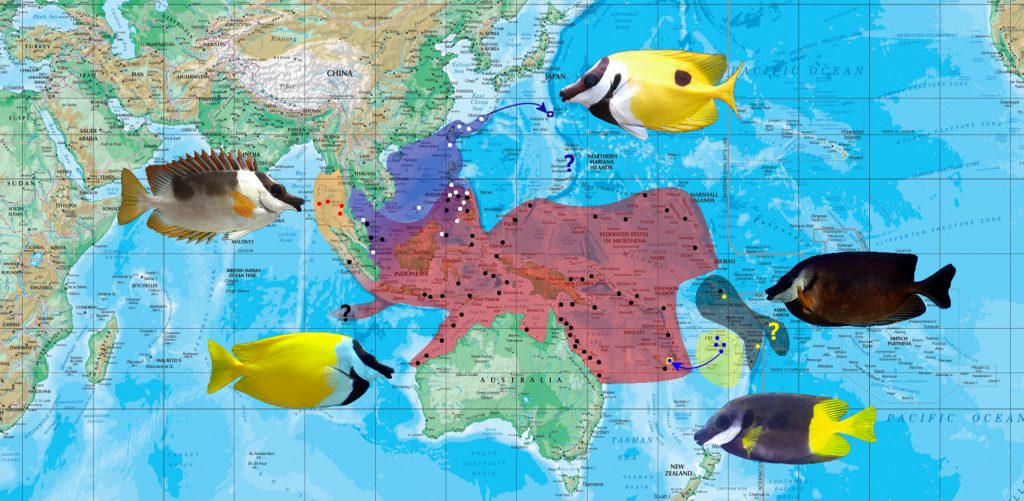

But what I find most fascinating about this group is their rather idiosyncratic distribution. There are five recognized species at the moment, with a range stretching from the Andaman Sea to Okinawa, Micronesia and just barely into Polynesia. One of the rarer and pricier of these fishes is the Magnificent Foxface (S. magnificus), which is apparently known only from a few reef systems in the Andaman Sea. It might be expected to occur elsewhere in the Eastern Indian Ocean, especially along Sumatra’s coastline, but, strangely, this very distinctive fish has seemingly yet to be found anywhere outside of its tiny known homeland.

The quintessential Foxface Rabbitfish (S. vulpinus) from Komodo, Indonesia. Credit: Mark Rosenstein

Moving into the Pacific, we find the familiar Foxface Rabbitfish (S. vulpinus) across a broad swath encompassing the entire Coral Triangle, as well as the Gulf of Thailand, Micronesia, the Coral Sea and as far east as Vanuatu. Clearly, this fish has done well for itself here, which makes one wonder why its Indian Ocean relative has done so poorly in relation. But things get more complicated when we journey north…

An unusual school of S. unimaculatus, at Okinawa. Credit: Mibai Hunter

The nearly identical Onespot Rabbitfish (S. unimaculatus) has a curious distribution, found as far north as Okinawa (though, strangely, not any further in the Ryukyu Arc) and south through most of the Philippines. Other records exist from the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea, from off northeast Borneo and some uncertain reports from peninsular Malaysia, where it is replaced by its immaculate relative. Genetic studies have thus far shown little difference between these two, suggesting that their split was quite recent and incomplete, allowing for extensive hybridization. Their biogeography conforms quite well with a faunal break in the region known as Wallace’s Line, first illustrated by the famed naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace. The root cause of this likely stems from periods of glaciation that lower sea levels, effectively cutting off the Philippines from reefs further south and allowing speciation to progress in isolation.

A Foxface (S. vulpinus) from Chuuk in Micronesia. It sure looks like the fish found in Indonesia and Melanesia, but is it truly the same? Credit: Dr. Dwayne Meadows, NOAA NMFS OPR

But the strange thing about S. vulpinus is how phenotypically consistent it appears everywhere else in its range. In many other groups of reef fishes, especially those with a tendency to form regionally endemic taxa, we expect to find a strong split between Indonesian and Melanesian populations, such as that seen in Chaetodontoplus mesoleucus and C. poliourus. But not here. The foxfaces of Micronesia are all but identical to those in the Java Sea and the Coral Sea. It’s hard to reconcile this incongruity, and we might expect to someday find evidence in their genomes for several cryptic “species”. The absence of this group in Japan is also particularly striking, given how widespread it is elsewhere, as is the vacancy in the Mariana Arc… but, why?

The Bicolor Rabbitfish (S. uspi), from Fiji. Credit: Mark Rosenstein

Things get even more complicated when we venture into the South Pacific. At Fiji, which marks the easternmost edge of Melanesia, famous for its high rate of endemism, we find the unmistakable Bicolor Rabbitfish (S. uspi). The melanism of this fish is taken a step further by the Black Foxface, a dismal, wretch of a species known only from Tonga and Tuvalu and rarely seen in aquarium exports. Both of these island groups, along with poorly studied areas like Samoa and Wallis & Futuna, are considered to be part of a broader Polynesian region that stretches east to Hawaii, the Marquesas and Easter Island. We see this same pattern of speciation in other reef fishes in this area, such as with the Meiacanthus fangblennies—a study of stony coral biogeography has likewise highlighted the unique qualities of this region’s fauna. But we still don’t have a good understanding for the fundamental causes that ultimately drives this speciation to occur. The islands of Fiji and Tonga are both quite old by Central Pacific Ocean standards, but the distance separating the two is fairly insignificant… so what conditions have fostered the emergence of these two distinctive foxfaces? Tonga, why is your foxface black?

The ugly duckling of Polynesia, Siganus niger. A disappointing foxface if ever there was one. Credit: Remix

As tends to be the case, I don’t actually have any answers to the questions I’ve posed here. But it’s still important to ask them. Why are these five species of foxface found where they are, curiously scattered across the Indo-Pacific in such a whimsical manner… how did they get there… where are they going?

Great article! i never thouth that even fish species may become seperated like this and form new species. I learned a lot from this text. I had no idea they form pairs or that Magnificent foxface is so rare in its distrubution. Onto the question – why does one spot foxface have a spot? It may be possible, that the ancestor to siganus vulpinus and siganus unimaculatus may have lived in the south, near australia and perhaps then as siganus vulpinus stayed in its original range. siganus unimaculatus made the journey north, where it met new challanges, lets say, meeting new type of predator, that didnt live in its original range. Thus unimaculatus perhaps had a lucky mutation, with a spot on its back that helped the individual evade predators better, as predators may have mistaken the spot as an head, and attack the wrong body part, giving the spotted individual better chance of surviving the attack. Perhaps then as spotted individuals spread north, where vulpinus couldnt follow the 2 could no longer breed between each other as easily, resulting in them becoming different species. And maybe this happened only recently and the progress of these two becoming different species is still going on, this would explain why are they so simmular and some individuals are still breeding between each other. This is only my hypothesis, so its plausible that this isnt nearly correct, however in my opinion at least. This would make sense. Probbably the same happened with other species of foxface rabbitfish, only a longer time ago meaning the differences are more visible. Thank you for now and goodbye