Hawkfish are attractive, hardy, small fish that are commonly available in the aquarium hobby. Even Fishbase points out that they “adapt well to aquarium conditions”. They are common fish all over the tropical and sub-tropical oceans of the world, and catching them for the aquarium trade doesn’t constitute a strain on the populations. But there are more reasons why these fish are attractive pets: they show interesting behaviors which fish biologists have elucidated.

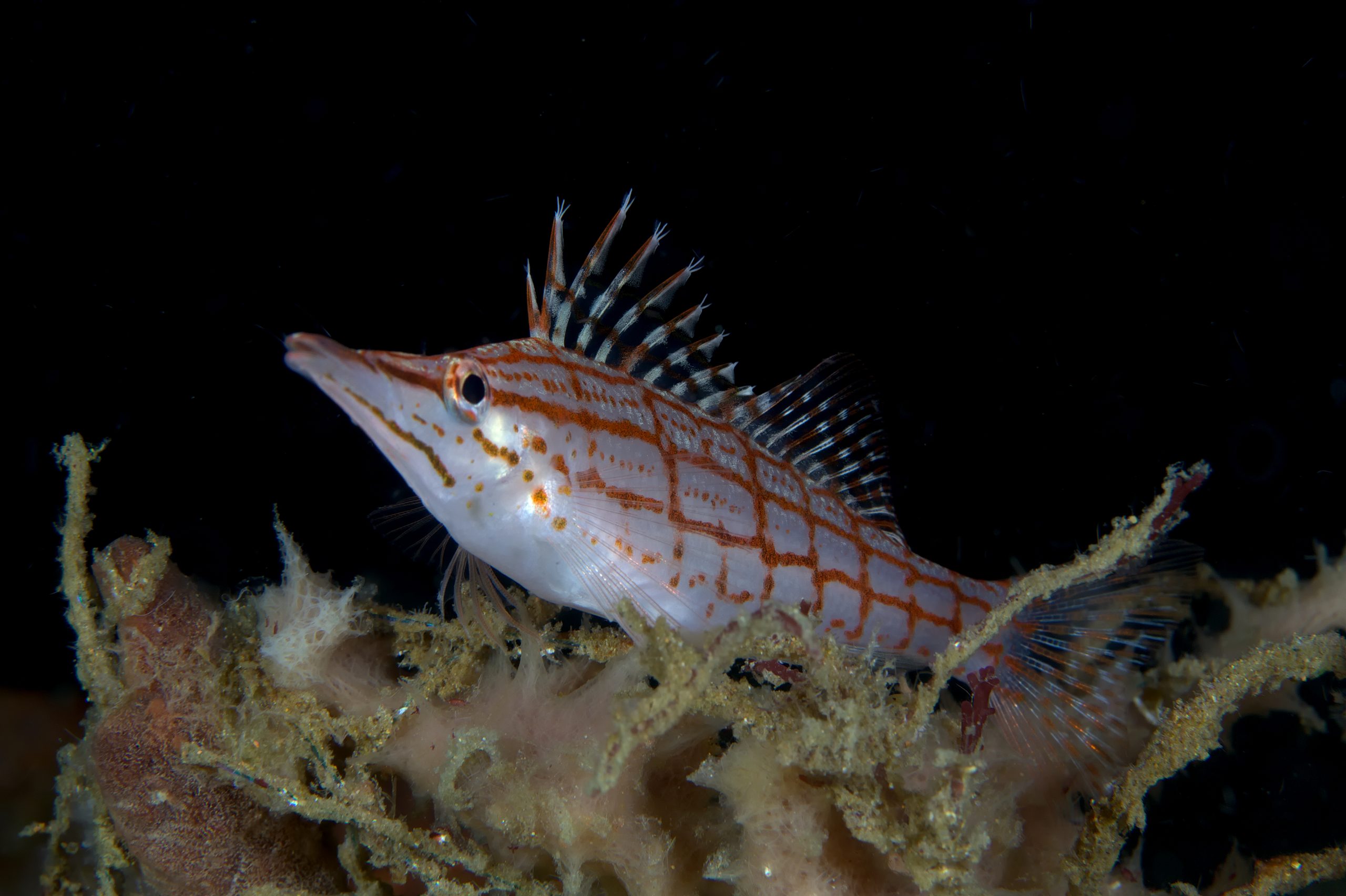

Cyprinocirrhites polyactis, Swallowtail hawkfish, Anilao, Philippines. Half hawk, half fish!

But first, we should look at the taxonomy of the Hawkfish. They belong to the family Cirrhitidae, and Fishbase lists 33 species in 12 genera. According to new research on the big picture of relationships between the bass-like fishes, the Hawkfish are most closely related to the Trumpeters (Latridae) and the Morwongs (Cheilodactylidae), two small families of marine fishes.

Hawkfish show interesting behaviors, some of which a patient aquarist can observe in a well-set-up tank:

Where they Hide

Hawkfish get their name from their tendency to perch in elevated positions on the reef, like hawks. They are quite selective when it comes to choosing the right substrate or coral for their liking. The longnose hawkfish (Oxycirrhites typus) prefers seafans, and so does the dwarf hawkfish (Cirrhitichthys falco). In contrast, the arc-eye hawkfish (Paracirrhites arcatus) prefers to hide out in between the branches of hard corals. DeMartini (1996) studied these fish in Hawaii. The marine biologist observed the fish for a period of five years, and some individuals over the course of one year. Recognizing a combination of size and color patterns made it possible to repeatedly identify individual fish.

It turns out that hawkfish are very tactical about where they spend their time. When they perch, and possibly hide form larger predatory fishes, they spend the majority of their time between the fingers of the hard coral Pocillopora rneandrina. The fish chose a different environment to hunt: when they strike out to capture prey, they did so on rock and dead coral rubble. This is a very clever way to reduce risk to themselves (it’s safe in between the hard coral fingers) and maximize pre capture (easiest in the open sand or rubble planes).

Paracirrhites arcatus, Arc-eye hawkfish, in its typical pose between the fingers of a hard coral. Okinawa, Japan.

The arc-eye hawkfish occurs in several color morphs, notably white-striped and melanistic, which means uniformly olive-brown. Do these color morphs go hand-in-hand with certain depths, types of habitat, or geographic regions? DeMartini and colleagues investigated this interesting question over the course of nine years. In hawkfish, the color morphs are not related to sex or developmental stages (as in angelfish, for instance, where juveniles are colored very differently from adults). Over all oceanic islands in the Pacific sampled, the white-striped morph was the most common, with 82% of the arc-eye hawkfish showing this coloration. The melanistic morph was still in the minority, but was more commonly found around the Hawaiian island of Oahu. This is more so the case on semi-protected leeward reefs; why exactly this is the case is still unclear.

The white-striped color morph also occurs more when the coral cover is less dense, and in deeper waters, probably because corals are less dense at greater depth. The two color morphs differ in how striking they look, both to the human eye as well as to other fish. This is most likely a very subtle interplay between being conspicuous to other fish of the same species and inconspicuous to predators or prey, shaping the ratios of color morphs in different habitats with different risk levels: areas with sparser coral cover are more risky.

The studies describing the substrate use and the color morphs of hawkfish are almost 30 years old, but good science doesn’t have an expiration date! No one should disregard the nine years (!) of fish watching which went into these studies, just because it was done in the 80s and 90s.

Oxycirrhites typus, Longnose hawkfish, Malapascua, Philippines. These fish are commonly found on sea fans.

What They Eat

Hawkfish are predators. In aquaria, their recommended diet consists of feeder shrimp and frozen marine meat preparations. But what do they feed on in nature? Stephania Palacios Narváez and colleagues analyzed the gut contents of the coral hawkfish Cirrhitichthys oxycephalus, off Isla Gorgona in Colombia. The stomachs of the fish mainly contained a wide variety of crustaceans, plus small fish and mollusks. Two findings stand out: the crustaceans included planktonic organisms, meaning that this species of hawkfish picks off food not just from the substrate, as would be expected for a perching, bottom-living fish but also feeds from the water column. Also, the fish ate isopods of the genus Gnathia, which are fish parasites. These parasites have a life-cycle like ticks, with blood-sucking while attached to their host fish alternating with a free-living stage in the rubble or among corals. Fish parasites have a big influence on the populations of fish in coral reef habitats, by draining their hosts and reducing their growth and reproduction. The fact that hawkfish feed on parasites will tip this ecological balance in interesting ways, away from parasites, towards more readily thriving fish in their immediate vicinity. The diet of this hawkfish will likely positively influence the rest of the fish fauna in this indirect way.

Cirrhitichthys falco, Dwarf hawkfish

How they Reproduce

Hawkfishes are protogynous hermaphrodites, meaning they switch sex during their lifetimes. They are female when smaller; and once they reach a certain size, their gonads change from ovaries to testes and the fish reproduce as males from that point on. This is not an uncommon strategy in fish, and is shared, for instance, with wrasses. The switch optimizes how much a single fish can reproduce during its life: when the fish is small, it can’t yet defend a territory as a male has to, and has better chances to produce offspring as a female. Only when big enough to fend off competitors does it turn into a male, and produces more offspring in this way.

As so often in biology, this clear and convincing story more or less holds true, but has interesting exceptions. Hawkfish organize in harems; in many species a large male mates with several females residing within its territory. In the dwarf hawkfish, Cirrhitichthys falco, the female to male transition can be reversible in exceptional cases. In a study by Kadota Tatsuru and colleagues, the scientists observed that once all females disappeared from the territory of a male, it sometimes reverted back to being a female. The new female was then able to join the harem of a neighboring male and keep reproducing. This doesn’t always happen, though: particularly large dominant territorial males waited out periods without females in their territory, and resumed reproducing as males once new females entered their spheres of influence.

I hope this article will inspire aquarium keepers of the different hawkfish species to observe their tanks even more closely; the territories of the dwarf hawkfish observed by Kadota were between 9 m2 and 52 m2, with the smaller female territories overlapping with the bigger male ones. Setting up a tank big enough for a whole hawkfish harem would be difficult; but the feeding behavior, and the space use (corals for perching/open areas for hunting) is something which can be observed in a tank.

Cirrhitichthys falco, Dwarf hawkfish, coming right at me.

References

DeMartini, Edward E., and Terry J. Donaldson. “Color morph-habitat relations in the arc-eye hawkfish Paracirrhites arcatus (Pisces: Cirrhitidae).” Copeia (1996): 362-371.

DeMartini, Edward E. “Sheltering and foraging substrate uses of the arc-eye hawkfish Paracirrhites arcatus (Pisces: Cirrhitidae).” Bulletin of marine science 58, no. 3 (1996): 826-837.

Kadota, Tatsuru, Jun Osato, Ken Nagata, and Yoichi Sakai. “Reversed sex change in the haremic protogynous hawkfish Cirrhitichthys falco in natural conditions.” Ethology 118, no. 3 (2012): 226-234.

Palacios-Narváez, Stephania, Bellineth Valencia, and Alan Giraldo. “Diet of the coral hawkfish Cirrhitichthys oxycephalus (Family: Cirrhitidae) in a fringing coral reef of the Eastern Tropical Pacific.” Coral Reefs 39, no. 6 (2020): 1503-1509.

0 Comments