By James W. Fatherree, M.Sc.

Sometimes called the disc or mushroom corals, the plate corals are regularly offered to folks in the hobby. Many are brightly colored, or at least neat looking, and they tend to be quite hardy, too. So, plate corals can be great additions to a reef aquarium. Let’s take a look at this bunch of stony corals, and go over their basic biology and their care requirements in aquaria. I’ll also fill you in on a few other things about them, which are often quite a surprise.

Most of the plate corals offered to us belong the genus Fungia, but there are some others that can be found on occasion. Examples of these would be members of the genera Cycloseris and Diaseris, Regardless, without a close examination of their skeletons and some detailed identification information on hand, hobbyists will likely have a difficult time trying to figure out what’s what.

Luckily, the various plate corals are similar enough that a proper identification (or rather a lack of one) shouldn’t really matter though, as they all have the same basic care requirements. You can treat all of them pretty much the same. Also note that there are other types of corals, which still belong to the same family as the plates, including the tongue and slipper corals (like Ctenactis, Herpolitha, and Polyphyllia), but I’m sticking with those that go by the common name plate coral.

When it comes to the basics, these corals are actually single polyps that are typically round or close to round and flattened, and they don’t form colonies the way many other stony corals do. They also have a single mouth right in the middle that can be seen as a little dent or elongated depression, and many can get relatively large. In fact, some can grow to well over a foot in diameter at full size. However, despite their potential to get big, they still have relatively short tentacles that are often kept out of sight during the day. They can also come in a broad range of colorations from solid pink, to fluorescent orange, to mottled blue and cream, and many things in between.

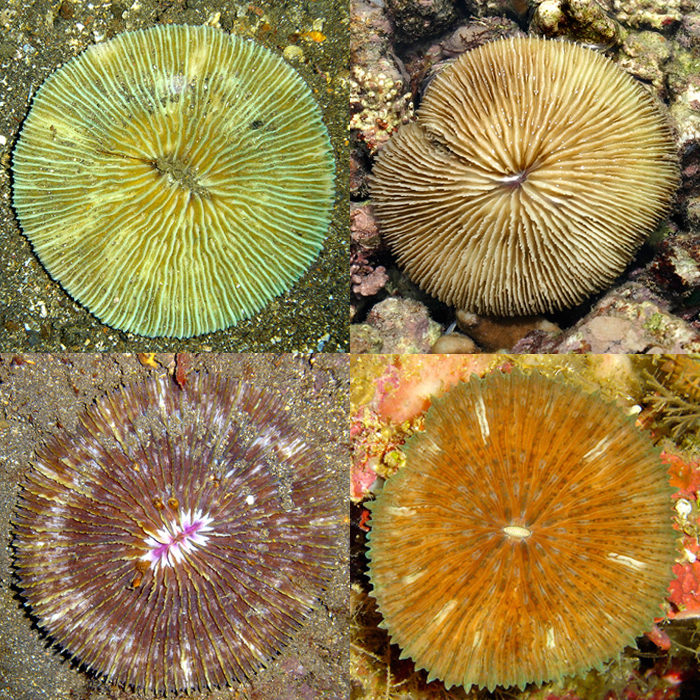

Some plate corals display outstanding coloration, and as you can also see here, they can also live on hard or soft substrates.

These corals are also free-living as adults, meaning they don’t stay attached to anything. However, they’re typically attached to hard substrates when they’re small, eventually breaking free from whatever they’re stuck on when they get big enough. Once detached, they can be found on sandy/soft bottoms, on rubble, on solid bottoms, or even on other corals at times. So, they don’t seem to be picky at all when it comes to what they sit on.

With that being said, if for some reason a plate coral isn’t happy with its location, it’ll actually crawl somewhere else. As strange as that might sound, they can move across the substrate under their own power. While they typically don’t expand their flesh very much, they can fill themselves with water and blow up sort of like a water balloon when they want to. By expanding some parts of their soft body this way and deflating other parts in the right sequence, aided by the use of some muscles, they can actually move themselves around, albeit at a much slower pace than a snail’s.

These are examples of specimens that have produced anthocauli, which are still attached to the skeleton of the deceased parent.

On occasion they’ll even climb around on rockwork, too. To add, if they aren’t getting enough light, they’ve been known to climb from the bottom onto rockwork to get themselves higher up (or at least try to). So, don’t be surprised if you put a plate coral in one spot and find it in another the next morning. Smaller ones can even flip themselves over if waves or a tumble down a slope ends up turning them upside down. This is obviously an important ability, considering that these corals live unattached and would die the first time they got flipped over if they couldn’t fix the situation.

I’ll also throw in another odd thing about them. They can reproduce in a very unusual way at times, via the production of things called anthocauli. What happens is that a parent coral will actually shrink though a process that’s called decalcification and simultaneously produce a number of smaller versions of itself, complete with little skeletons. This typically occurs if a parent coral is injured or stressed, and the new little corals are the anthocauli. Basically it seems that if the parent is in trouble, it will use itself up to make smaller versions of itself, which may have a better chance of surviving. Thus, an occasional plate coral may be covered by temporarily attached miniature versions of itself, which will eventually detach and disperse as they grow.

Here are a few polyp buds, which have dropped down from the edge of a long-tentacle plate that’s not in the picture.

Aside from that, plate corals can also reproduce sexually by spawning, spewing out sperm and eggs in to surrounding waters, and can form polyp buds as a second means of asexual reproduction, too. Polyp buds are sort of like anthocauli, except that there is no shrinkage of the parent, and it isn’t a reaction to injury/stress. It’s the “normal” means of asexual reproduction. Small buds of flesh form on the parent, which grow their own little skeleton, and then are pinched off so they can start life on their own.

When it comes to aquarium life, these corals are typically quite hardy and relatively easy to care for. They can thrive under moderate to high intensity lighting, with a low to moderate current passing over them. Currents that are too strong will cause them to stay retracted in their skeletons though, as they won’t extend their flesh, so don’t overdo it. Water quality should be excellent, as is the case with any corals, and you can put them right on the bottom of a tank, whether it’s just bare glass or is covered by sand, gravel, or rubble. Of course, if you choose, they can also be placed on rockwork too, as long as they’re in a spot where they won’t go crashing down to the bottom from up high if they start to move around, or fall into a crevice in the rocks.

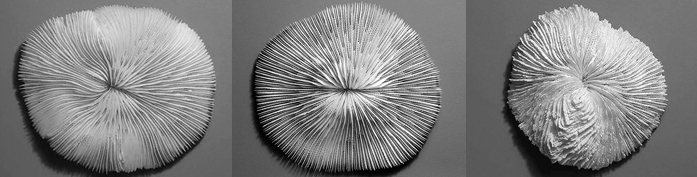

These are skeletons of typical plate corals. It’s easy to see that there’s not much flesh on these corals, as the skeletal form is still visible when covered by living tissue.

There are a couple of other things to note here, though. Keep in mind that if they get covered up by sand that is moving around in a tank, they do have to expend energy/resources to clear themselves off. By producing copious amounts of mucus, which can be moved across their surfaces by microscopic hair-like cilia, they can transport sediment off themselves, but it’s a bad idea to put one in a position where it will constantly have to work to keep itself cleaned off if you have sand in your tank and it gets blown onto the coral regularly.

Also, while plate corals don’t seem to mind touching other plate corals, and can often be found in huge aggregations in the wild, they generally won’t like being touched by other corals. They don’t have the tentacles needed to do any fighting at a distance, but in response to any unwanted direct contact they’ll typically produce large amounts of toxin-bearing mucus and can actually slather an offending coral to death. So, be sure to keep them from getting too close to other non-plate corals or one of them will likely be injured/killed.

Not all plate corals grab your attention the way fancy ones can, but they’re still neat looking and easy to care for corals, nonetheless.

When it comes to feeding, plate corals can capture zooplankton on the reef, but there typically isn’t much of that in an aquarium. So, you can give them a little food if you think a plate isn’t getting what it needs. There are zooplankton products on the market that can work well for many types of corals, and you can also give them something larger, too. I oftentimes fill up a big needle-less syringe with some brine shrimp or shrimp/clam meat that’s been finely chopped and give corals a little squirt of the stuff. In response, plate corals will often open up their mouths and slurp in whatever they catch. You do have to be careful not to overdo it though, lest you negatively affect the water quality. It’s a good idea to turn off the pumps and such for a few minutes too, so that any food delivered to one doesn’t just get blown away. You should also feed the fishes really well beforehand, or they’ll usually try to steal the food given to the corals.

Is the addition of such foods required? Maybe, maybe not. I’ve always given my corals a little food now and then, and haven’t tried making them go without, but I’ll assume that there are some hobbyists out there right now saying, “I’ve never fed mine anything and they look great.” I’d have to say it probably depends on numerous things, like the lighting, the amount of dissolved nutrients in the tank, the use or lack of a deep sand bed or refugium, the species of coral, it’s size, etc. I’d rather not take any chances myself…

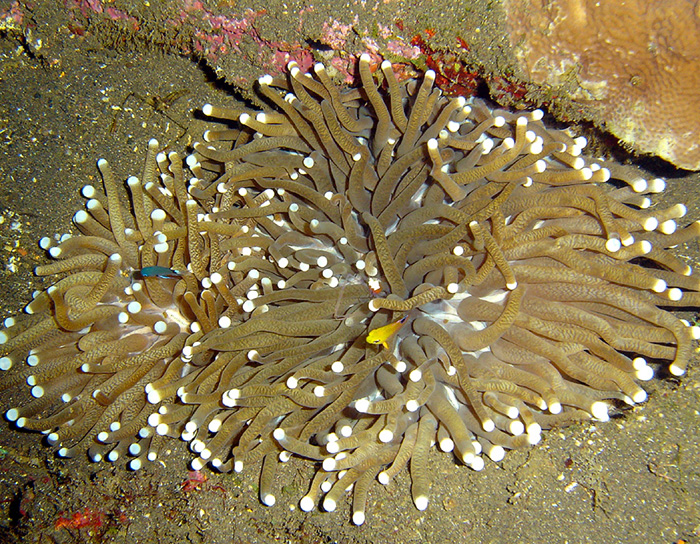

Now with the basics covered, there’s one species of plate corals that is quite distinct for the rest. Instead of having short or no tentacles at all, the long-tentacle plate coral, Heliofungia actiniformis, is covered by so many long tentacles that they can be easily mistaken for an anemone.

The long-tentacle plate coral can easily be mistaken for an anemone, as its tentacles can completely obscure the body and skeleton.

Like the rest of the plate corals, the long-tentacle plate coral is also a relatively large and free-living, with a flattened disc-like skeleton. However, they possess tentacles that are some of the longest of all the stony corals, which can easily obscure the entire body and skeleton. As far as coloration goes, they typically don’t come in the wide range of colors that the other plates can come in either, as they’re usually brown or green with light-colored tips at the ends of their tentacles, and sometimes have contrasting light-colored stripes on the body, too. Apparently they don’t form anthocauli, either, but do produce polyp buds.

Long-tentacle plates can also be placed on soft substrate or rubble, but should be given plenty of room, well away from other corals, as the long tentacles are loaded with stinging cells. They’ll also need moderate to high intensity lighting, and the presence of the tentacles is likely an indication that they rely on the capture and eating of prey items much more than the other plates do. So, I’d be sure that one of these gets some food from time to time to keep it in top shape.

Lastly, I’ve got some information about shipping and handling. Plates are generally tough corals, but the ridges on the skeleton are very sharp and they can end up cutting a coral’s soft flesh if a specimen gets banged around during collection and shipping. So, you need to watch out for any plate coral that has any lacerations/injuries. Bad ones are easy to spot, as the white skeletal material can be seen protruding from the flesh, but smaller injuries won’t be so noticeable. So, look close.

Look closely and you can see an area affected by tissue recession at the top right edge of this oblong plate coral. A small portion of the white skeleton is completely exposed.

Another common problem is tissue recession, which can be seen at the edges of a specimen where the flesh is simply gone, leaving some part of the skeleton completely exposed. If the skeleton has been exposed like this, it can often be overgrown by algae, which can be problematic for the coral when it tries to recover. So, again, take a close look, as you might not see the problem so easily.

That’s about it though, other than obvious breakage or some other serious problem, which would be easy to spot. I would also pass on any long-tentacle plate that doesn’t have its tentacles fully expanded. Other than that, keep in mind that the soft tissue is fragile, so a well-expanded plate should be given a little gentle prodding in order to entice it to retract its flesh before lifting one out of water. The same goes for long-tentacle plates, too. Get them to retract their tentacles before picking one up, just to be sure that they don’t get injured in the final leg of their journey from the sea to an aquarium.

References

Borneman, E.H. 2001. Aquarium Corals – Selection, Husbandry, and Natural History. Microcosm/T.F.H. Publications, neptune City, NJ. 464 pp.

Veron, J.E.N., 2000. Corals of the World: volume 2. Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville. 429pp.

0 Comments