By Richard Aspinall

One of the most exciting parts of setting up a marine aquarium for the first time is the introduction of corals, but the process can be nerve wracking, especially to the newcomer to the hobby. This is entirely understandable, just about all of what we might consider corals are sessile. They may be able to move over a very long time period, but in the main any coral is entirely dependent upon the aquarist to give it the conditions it needs to thrive, it can’t swim away and sulk like a fish, it can’t skitter away and lurk under the rockwork like a crustacean or echinoderm. Every aspect of its environment is controlled by the aquarist and if we don’t get it right we are dooming a remarkable living organism to an uncertain fate.

Having said that, even an experienced aquarist should not add a new coral without a certain degree of concern for the welfare of their existing stock as well as the new specimen – and that is how it should be – but more of that later.

In this piece I shall offer a straightforward (and very simple), overview of the basic conditions that corals require in captivity and how we maintain them and then I will look at how to add some of what I would regard as the most straightforward of corals for the beginner.

Stability

The key to maintaining healthy corals over the long term, be they delicate Acroporids or more hardy sessile invertebrates such as zoanthids, is stability. The more stable you as an aquarist can maintain the chemical composition and other environmental factors in your captive reef the less any inhabitant in the aquarium will have to expend energy to adapt to change. The closer those parameters are to those encountered in the coral’s natural habitat, the ‘happier’ they will be and the more likely they are to survive.

Clearly, no coral can realistically be described as ‘happy,’ but it’s a term many aquarists will use on occasion to describe the overall health and condition of a coral. When my corals are showing nice polyp extension, colour and growth I tend to think of them as being ‘happy,’ I can’t help it, even though I know I should perhaps describe them as ‘responding as expected to the conditions provided’ or something similarly more biologically accurate – however, I’ll stick with ‘happy’ as a biologically incorrect but practically useful term.

Whatever the terminology used, the closer the corals (and of course all the other organisms in the tank), are kept to the conditions in which they are best suited, the better they will grow. Take for example, the human body: our body tissues are kept within a very narrow range of conditions; temperature, pH, osmotic balance, electrolytic concentration etc… our bodies work very hard to maintain these balances – a process known as homeostasis – when they are out of kilter we rapidly succumb to stress. Sessile invertebrates are constantly bathed in their environment, maintaining homeostasis for them is a different, they are adapted to conditions that show very little variation. We have a nice coating of skin to keep the environment out and the good stuff in – corals do not.

Keeping corals happy within conditions that they are adapted to relies on us mimicking the conditions found in the wild and doing our best to recreate the conditions found in natural sea water (NSW). Much has been written on the subject of NSW, mostly by people with far greater expertise and knowledge than I, but in essence, sea water is an incredibly complex mix of dissolved chemicals and particulates that find their way into the oceans through dissolved substances entering them via river runoff and erosion, precipitation and entry of solutions and substances though geological processes. The resulting chemistry is further adjusted through what we might call ‘life processes.’ Simply put, many of the components of NSW would be missing or different (to a greater or lesser degree), if life was not present. The most obvious of these must be the presence of oxygen, another very relevant sea water constituent might be the calcium dissolved from rocks (often from an earlier marine origin) that is converted in coral skeletons.

NSW Characteristics

NSW is a highly complex mixture of non-organic and organically derived substances (and of course an awful lot of living material, but I’m ignoring that for the sake of brevity). Many of these substances exist at levels so minute that it is hard to accept that they play any role in biology, yet many do, for the sake of argument we can call these ‘trace elements.’ Of more immediate concern are the dissolved substances that contribute to the basics of successful marine aquarium keeping: salinity, alkalinity, and calcium and magnesium levels.

Salinity and the ‘Big 3’ are the most fundamental of the parameters that the aquarist needs to maintain, with the chemicals responsible existing at the very measurable gram per kilogram of water level and contribute to the bulk of the salt you haul home from the LFS. I’m taking it as read that anyone keeping a marine aquarium is maintaining a stable salinity in the region of 1.024 to 1.027 (35 parts per thousand or thereabouts). Salinity can be allowed to vary, but very slowly (over the course of weeks – if yours has drifted don’t rush to change it, don’t add any extra stress to your animals and never add salt directly to the tank!), salinity does not change significantly in coral reefs with the exception of those habitats that receive freshwater inflow from rivers or perhaps in some shallow areas where rainfall or evaporation may be a factor during low tides – but in the main, on the high current areas of reefs, salinity does not fluctuate appreciably. Some bodies of water such as the Red Sea have a relatively high salinity (39ppt on average), but the life encountered therein is adapted to a higher salinity level.

Major and Minor Constituents of Seawater

Ion % by weight

Chloride (Cl-) 55.04

Sodium (Na+) 30.61

Sulfate (SO42-) 7.68

Magnesium (Mg2+) 3.69

Calcium (Ca2+) 1.16

Potassium (K+) 1.10

Total 99.28

Bicarbonate (HCO3-) 0.41

Bromide (Br-) 0.19

Boric Acid (H3BO3) 0.07

Strontium (Sr2+) 0.04

Subtotal 0.71

Total 99.99

Nybakken, 1993.

In this article I will look at the major components that an aquarist needs to get right to begin with, again much as been written about the need for adding trace elements and there are as many opinions on the subject as there are aquarists. I have visited some fantastic tanks that employ a complicated dosage schedule and others that receive simply a small addition of a proprietary trace element mix. Some additives are snake oil, some are useful, it is difficult for the newcomer to wade through the marketing sometimes.

The need for trace elements is now far more understood, especially in maintaining the coral’s pigments for example, but how they are provided varies. Usage of a calcium reactor frees up trace elements locked up in the coral media being dissolved whereas regimes such as Balling Light require the addition of extra elements in quite precise ratios to the solutions being dosed. Some aquarists will add iodine, others will allow the iodine in the marine algae they feed their fish to find its way into the water column. However, for the beginner, the best approach is to look to a good quality salt mix as a start, along with regular water changes to supply and maintain levels of trace and elements. Aquaria that have an increasingly large amount of life within them are likely to require a correspondingly greater amount of additions as time passes and the biomass increases relative to the water volume, but this is perhaps a problem the newbie might not encounter for some time.

The Big 3

After salinity, the most important parameters to maintain are calcium and magnesium levels and of course alkalinity:

Calcium

Calcium needs to be maintained at around 400-450ppm in the aquarium. It is the main constituent in the formation of coral skeletons (calcium carbonate as aragonite), and the shells of creatures such as Tridacnid clams. It can be maintained using over the counter solutions, kalkwasser additions or more commonly via a dosing regimen such as Balling Light or a calcium reactor. Maintaining calcium is not difficult, but it should not be varied by more than 20ppm a day and as the amount of coral in a tank increases the amount of calcium added will need to be increased.

Magnesium

Being a copreciptate in skeletogenesis, magnesium is important in coral growth and in many life processes, though the amount of magnesium locked up in coral or coralline algal tissue is far less (<2%) when compared to calcium. Once again magnesium can be added via liquid solutions, but is best added via a dosing regimen or via a calcium reactor. The benefit of adding it with a calcium reactor is that as the media dissolves the ratio of calcium to magnesium is maintained correctly. Try to maintain magnesium at around 1250-1350ppm in your tank.

Alkalinity

The alkalinity of our systems is a complex matter that is determined by the presence of many organic and non-organically derived materials, not least the addition of substances like calcium and magnesium and the by-products of biological processes. The relationship between calcium and alkalinity is a complex one, the practical upshot being that the addition of calcium to a tank can cause the precipitation of calcium out of suspension as calcium carbonate onto the rockwork and substrate, along with the consequent reduction of carbonates in the water, this which will drive down the water’s pH. The subject of calcium and alkalinity balance is the subject of many more articles, some of which are quite complicated if chemical formulae are not your favourite reading material. In essence though, be aware that additions to adjust one parameter can effect change in another.

Test kits for alkalinity are easy to use and reliable, a figure of between 7-and 12 dKh is considered ideal. Many aquarists will maintain their alkalinity at the higher end of this scale to provide an increased amount of buffering capacity which is useful in a volume of water vastly smaller than the ocean.

For me, the best way of ensuring the Big 3 are in the correct balance is the use of a good quality calcium reactor, which may be a hassle to set up initially, but when running correctly will deliver the bulk of the Big 3 in the correct ratios by dissolving the same substances the corals are using to build their skeletons, i.e. old coral skeletons. Water chemistry is a complex subject, and the beginner needs to understand that there is a lot more going on than may at first be apparent. However, with small changes to a systems water quality and regular testing the aquarist will develop a sense of how each adjustment varies the conditions within the aquarium.

Temperature, Flow and Light

I’m going to also assume that anyone reading this is maintaining their aquarium within the correct temperature range and that any temperature variation is kept low or ideally non-existent with the use of chillers if necessary.

Water flow presents another enormous subject for discussion. Bear in mind that on the majority of the world’s reefs, water movements can be considerable. This isn’t of course the same for every coral, and those that are found in deeper waters may not be best suited to high flow areas. Consider the differences between a torch coral and a staghorn Acropora. The former will be ripped to shreds by vigorous water movement, whereas the latter will thrive on it. The key here is to talk to the staff at your LFS and do your research.

In terms of lighting, most commercially available lighting advertised as suitable for keeping corals will be able to do so, the main risks for the first time coral keeper is fitting high intensity lighting to a tank and ‘blasting’ corals and inverts with strong lighting that they are not accustomed to. Even species and genera that are tolerant of very strong lighting in the wild may require time to adjust to lighting in the captive tank, especially with some of the lighting units using LED technology that generate ‘hotspots’ directly under the arrays. Again do some research and when you introduce your corals to your tank consider placing them on the substrate away from ‘hotpots’ and raise them to their final position in the tank over a period of a week or two. I would rather a coral lose colour and require extra lighting to be added or it to be moved rather than bleach it from too intense a light source.

Bear in mind also that many corals (for sake of argument we’ll say the bulk of LPS), such as Acans, Favias, Lobophyllians etc… are best kept in the lower reaches of a tank which is fitted with high intensity lighting.

Again, the best advice for the newcomer to the hobby is to chat to other aquarists and seek out knowledgeable staff at stores. Bear in mind that if someone in the store won’t sell you a coral, they are perhaps doing you a favour and you should not be offended.

Quarantine

Aquarists with extensive collections of corals will be very wary of adding corals to their systems without quarantining them first in the hope of identifying any disease or pest organisms before the infection becomes manifest in the main aquarium. It is likely that the newcomer won’t yet have set up an isolated system for such a purpose. If this is the case consider one of the many coral dips available which can be used to treat corals to remove potential pests like coal eating flatworms.

Acclimation

It should be obvious that any addition to a tank will require acclimation, that slow process of adjustment from the water in the bag from the store to the water in your tank. Whilst the ‘floating bag trick’ might be acceptable (just) for robust fish it is not really suitable for inverts, where a slow drip-feed method is best. I have taken a feed from one of my pumps, fitted it with an inline valve and now have a highly controllable supply which I can drip into the coral’s water in order to make changes as slow and gradual as possible. This process often takes many hours.

Some Easily–Kept Corals

Any aquarist will quickly learn that coral keeping is more complicated than the text above suggests, even though I hope it covers the simple basics. I hope though that it serves as a very brief introduction and covers the bare bones, enough to prompt the beginner to look beyond this brief intro and ensure that they look further into the detail.

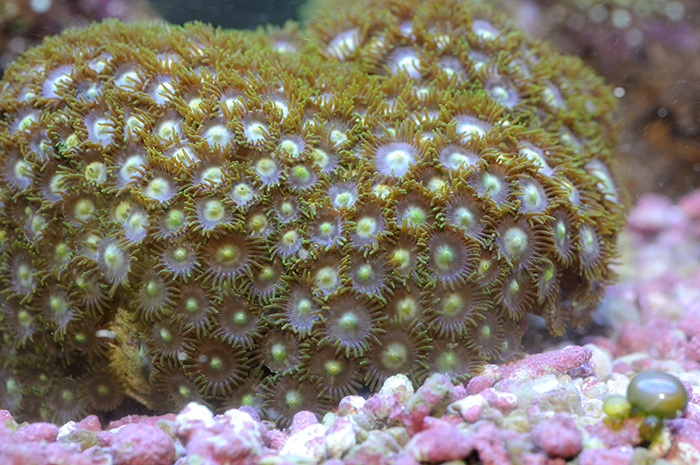

Zoanthids

Zoanthids, Zoas, button polyps whatever you call them are fantastic beginner’s corals in the main. Most zoas available at a frag swap, in the store or available online will be hardy, resilient and the chances are from a strain or morph that has been grown in captivity for that long it has proven itself as a variety ideally suited to life in a marine aquarium. They also look great under actinic lighting and are ideal for smaller and nano systems.

Zoas are found in a bewildering array of colours and have a very dedicated band of followers who are willing to pay significant sums of money for the rarest morphs, whilst common varieties are available for a few dollars per head or less. The small polyps grow from an encrusting ‘mat’ that will quickly and without any additional feeding cover rockwork in most tanks, to the extent that many people will grow each colony on an isolated plug or piece of rock and place it on the substrate to stop it spreading over adjacent rockwork and overgrowing other corals.

Zoas are found in a bewildering array of colours and have a very dedicated band of followers who are willing to pay significant sums of money for the rarest morphs, whilst common varieties are available for a few dollars per head or less. The small polyps grow from an encrusting ‘mat’ that will quickly and without any additional feeding cover rockwork in most tanks, to the extent that many people will grow each colony on an isolated plug or piece of rock and place it on the substrate to stop it spreading over adjacent rockwork and overgrowing other corals.

The taxonomy of zoanthids is complicated and most, if not all zoas are referred to by a name given them by aquarists that reflects their colour: dragon eyes, fire and ice, gorilla nipples, tangerine dreams, purple people eaters, oompa loompas and so forth are readily available.

The taxonomy of zoanthids is complicated and most, if not all zoas are referred to by a name given them by aquarists that reflects their colour: dragon eyes, fire and ice, gorilla nipples, tangerine dreams, purple people eaters, oompa loompas and so forth are readily available.

Many aquarists will not feed their zoanthids, and indeed some zoanthids don’t seem to elicit a feeding response, but many will take small items of food if offered. I have a dozen or so varieties that seem to thrive on gathering whatever nutriment they can from the water column and of course the results of their symbiotic algae.

Aquarists will quickly learn of the substance palytoxin, a chemical present in the Zoanthidae. This chemical, present to deter attack from hungry fish and foraging inverts can be dangerous to humans. The prevailing advice would suggest that anyone handling zoas should ensure they don’t allow the corals’ mucous that contains the neurotoxin, to touch broken skin. Hand washing is a must.

Aquarists will quickly learn of the substance palytoxin, a chemical present in the Zoanthidae. This chemical, present to deter attack from hungry fish and foraging inverts can be dangerous to humans. The prevailing advice would suggest that anyone handling zoas should ensure they don’t allow the corals’ mucous that contains the neurotoxin, to touch broken skin. Hand washing is a must.

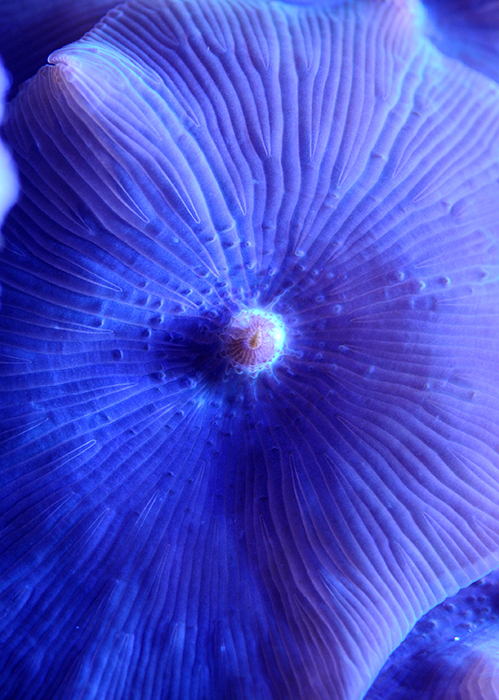

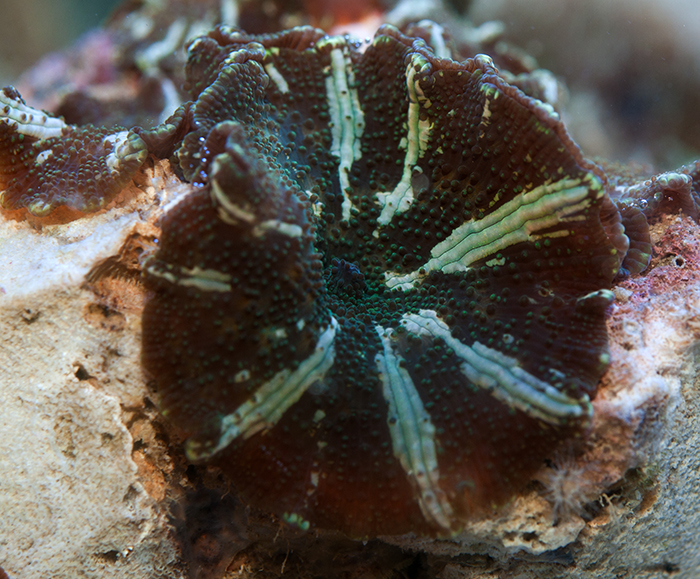

Mushroom Corals

Mushrooms are either a great beginner’s coral or a rapidly overgrowing weed according to many posts on various forums. I favour the former and indeed my first ever ‘corals’ was a rock covered in some luminous green ‘mushies’. Mushrooms or more accurately corallimorphs were once classified along with the anemones and are taxonomically tenuous according to Eric Borneman. Today the Corallimorpharia incorporates several genera including: Actinodiscus, Ricordea, Corynactis, Rhodactis, and Amplexidiscus.

Corallimorphs are very tolerant of water conditions and are considered as animals that can tolerate poorer water quality than many others (ideal perhaps for the newbie). Actinodiscus species, often available as red or blue morphs are very tolerant and will spread across rockwork with detached individuals growing wherever they fetch up. Most favor limited water movement and lower lighting than many reef tanks provide, which means that should they take over, they can be controlled by increasing flower and light output. Ricordeas however, are available in superb colours and seem to benefit from more light and flow than their cousins.

Mushies are capable of feeding, but in captivity many do not and get by on the products of their zooxanthellae and this is perhaps wise. Well–fed corallimorphs will spread and can sting other inverts that they come into contact with. Amplexidiscus species can take large items of food that falls upon their disc and may predate on small fish!

Like the zoas above, they do not form calcareous skeletons and the aquarist can be less concerned about calcium and magnesium levels in relation to these animals.

Corallimorphs are ideal for fragging and can be cut with sharp scissors or a scalpel to produce more individuals. Cutting them in quarters along the main axis and ensuring that each piece has part of the mouth remaining will result in four individuals.

The cut sections need to be allowed to heel and to attach to rock rubble in a low flow area of the tank or in a dedicated frag system. The cut animals will produce a lot of toxin-rich slime so ensure your system is running activated carbon to deal with the problem.

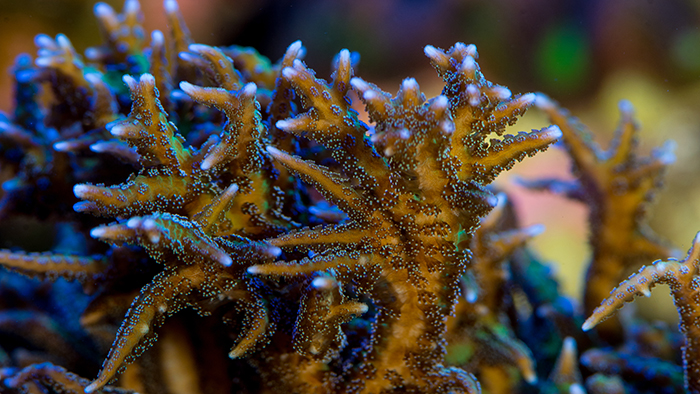

Seriatopora

The birds nest corals Seriatopora hystrix and S. caliendrum are what we might term ‘proper’ corals being from the stony or scleractinian corals and they are certainly within that taxonomically pointless but still useful grouping of SPS.

Whilst there are easier to grow corals and inverts in this list, I have found that S. hystrix is one of the best starter corals for aquarists wanting to try their hand at keeping SPS corals for the first time. This is partly due to the large amount of frags available (which helps) and the species’ tolerance of lower lighting levels than others. Seriatopora also seems to grow well without specific target feeding.

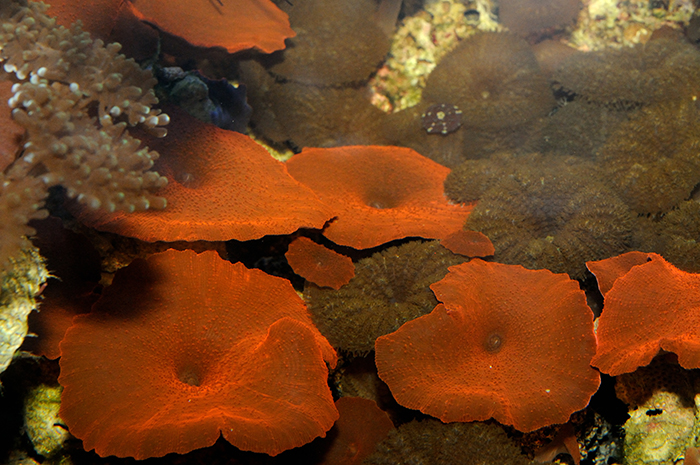

Montipora

The genus Montipora offers several robust and likely candidates for the beginner. Like Seriatopora they are quite forgiving, but will need calcium, magnesium and alkalinity levels to be maintained correctly to thrive and show their best colouration.

There are several species within the Montipora genus that can become confused. Many aquarists group Montipora species such as M. capricornis and M. turberculosainto the ‘plating montis’ category. Other species like M. verrucosa are more encrusting in nature, whilst M. digitata, as the name implies, is finger like in growth form and one of the best beginner’s species.

Plating montis and M. digitata can be quite fast growing and readily available as frags, the beginner can assume that if they are sourcing a frag from another aquarist the ‘stock’ in question is well suited to captivity.

Monti’s and the bird’s nest corals are ideal beginners SPS corals, they can be sourced easily and very often for free from other aquarists. If you ensure that the Big 3 are close to accepted norms, and the specimens you introduce to your tank are acclimated well and not placed in overly bright lighting upon first entry into the tank (remember, it is better to put new corals into dimmer lighting and increase the lighting over time than bleach them).

Duncan Coral

Duncanopsammia axifuga is a great coral, beloved by beginners and experts alike and is regarding as being able to adapt to a wide range of lighting conditions, though it is reported to be found in deeper waters in the wild. In a mixed reef Duncanopsammia is best placed in the middle of the tank with more light demanding corals placed in the upper reaches.

Duncan coral is definitely in the ‘LPS’ group, each coralite has a well-defined oral disc and series of tentacles which are often tipped in bright green to violet shades, a colony that has grown well and formed a mass of polyps looks very attractive in moderate currents and looks even better when the current is varied to show a range of movement across the polyps. Avoid very strong currents.

Whilst feeding Duncan’s is not absolutely necessary it is very much recommended. Frozen crustacean based food (once thawed and rinsed), such as Mysis are ideal as are some of the smaller pellets designed for LPS corals. I choose to feed my Duncan once my wrasse have gone to sleep on an evening and can’t steal food from them. I turn off the current and then gently squirt the food across the polyps using a turkey baster. Feeding once or twice a week will ensure extra growth.

The skeleton of Duncanopsammia is obscured by the large, fleshy polyps, but it is very much present and indicates that the coral needs the Big 3 to be maintained correctly. Once growing well, Duncans can use a fair amount of calcium so be prepared to increase your dosing rate as time passes.

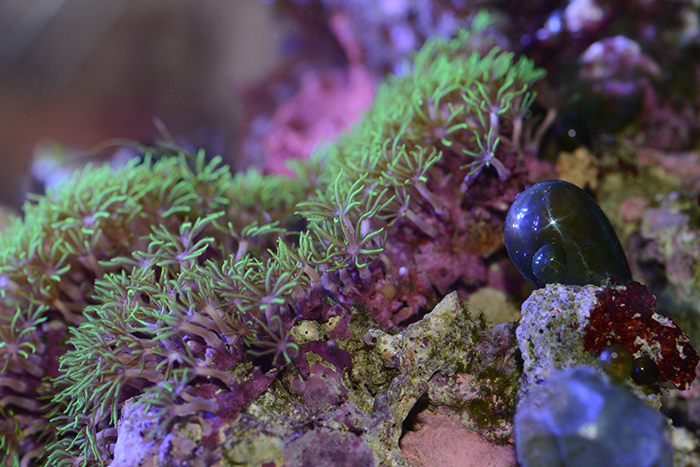

GSP

Green Star Polyps (GSP) is perhaps the quintessential beginners’ coral, with small frags or even whole chunks of encrusted live rock readily available. Some more accomplished aquarists may consider this easily kept species as not worthy of entering their tanks and some may seek to avoid allowing a rapidly growing ‘rock-coverer’ from entering their displays.

Personally I think that some of the very luminous varieties in bright neon green are just about as perfect as a coral can get and are great for covering a placed on the substrate to isolate them from spreading. When kept in this way they look great, pretty much always expanded, moving slightly in the current and resistant to hermits that often clamber over and through the polyps.

GSP, in as a manner similar to Zoanthids grows from an encrusting purple or violet mat, which can be peeled off and attached to other rocks and used to create some quite stunning creations. Attaching them to interestingly shaped pieces of life rock with elastic bands until they ‘take root’, works very well.

GSP spreading over rocks, showing the characteristic projections of the encrusting mat called stolons.

As noted though, GSP can spread well, especially when the nutrient level in a tank is high in my experience, so if you don’t want it to run rampant, do isolate it to a distinct location that you can remove later on if you wish.

Incidentally, there is some disagreement as to the taxonomy of GSP so expect to see various scientific names used from the genera Briareum, Clavularia and Pachyclavularia. Borneman (2009) describes GSP as Pachyclavularia violacea.

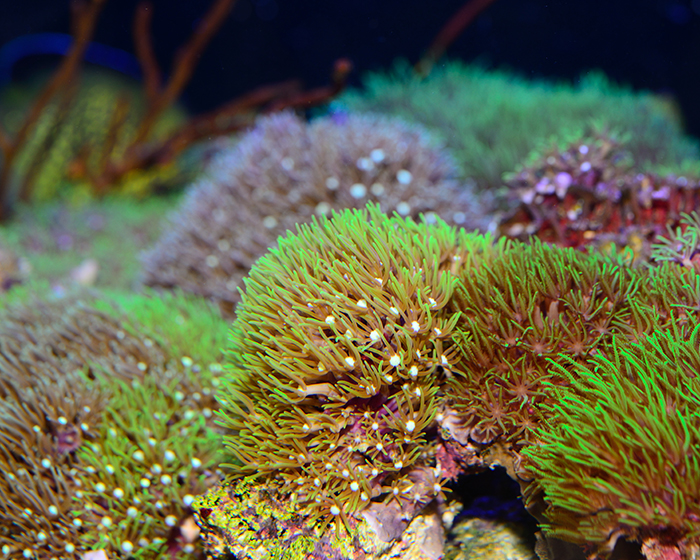

Xenia

Many people, myself included have mixed feelings about xenia, it is either a fascinating animal that displays unique behaviour or it’s a vigorous, toxic weed that can take over a tank. Finding a happy medium with xenia is tricky.

There are an estimated sixty or so species of xenia, though aquarists often refer to them with more descriptive terms such as ‘bushy,’ ‘elongate,’ or similar. Variation exists in the length of the polyps’ stalks, the degree of ‘featheriness’ and colour.

There are an estimated sixty or so species of xenia, though aquarists often refer to them with more descriptive terms such as ‘bushy,’ ‘elongate,’ or similar. Variation exists in the length of the polyps’ stalks, the degree of ‘featheriness’ and colour.

Xeniids are noted for their pulsating action in which the polyps contract and expand rhythmically, this can be quite fascinating and attracts many newcomers to the hobby who are understandably drawn to this behaviour, which has evolved to increase oxygen levels around the polyps according to some recent research – though not all colonies and species will pulse. Xeniids are able to colonise rockwork in the wild and in captivity very quickly and will ‘walk’ as they reattach their bases to adjacent rock. This process happens slowly, but compared to all other corals, it’s pretty speedy. Sexual reproduction occurs, but planate are likely to be removed via standard filtration methods.

Xenia colonies are also able to detach and allow themselves to be washed around the tank and can rapidly spread and crowd out other species. The growth rate of xenia and its concomitant spread is governed by nutrient availability (often high in newly established tanks) with many aquarists with very well-maintained tanks reporting that they cannot keep xenia at all. Personally I’ve had some great xenia colonies, but all have ‘crashed’ and withered away to nothing over time, this is no doubt a good thing in terms of a tank invasion averted but I do miss the pulsing and I have yet to identify the cause for such crashes, it seems I am not alone according to the literature.

There is still much to learn about the xeniids and much of the information regarding their care is anecdotal or even contradictory. Suffice it to say, introduce xeniids to your tank with care and consider that when disturbed (often when an aquarist is trying to remove unwanted colonies) the polyps can produce toxic substances so ensure your carbon is refreshed when dealing with them in the tank and/or try to syphon out the debris as you go to remove as much biomass and potential toxins as possible.

Despite the varying advice on xenia care, try to ensure a high pH and alkalinity which will help to ensure happy colonies of this opinion-dividing coral. Some reports suggest additions of iodine will maintain Xeniid health.

Euphyllia

Corals from the genus Euphyllia are understandably popular in the aquarium hobby, with colours ranging from neon green to pink and occasionally even sporting violet tips to their tentacles, Euphyllians are great additions to the reef aquarium.

These LPS corals build large skeletons that as they grow, which may form a branching structure in the case of E. parancora (branching hammer coral)or may be more compact in growth form in the case of Frogspawn coral (E. divisa) and torch coral (E glabrescens).

Euphyllians appear to welcome a range of water conditions but do best in indirect lighting and moderate flow. Whilst various colour forms are noted, in the main the colours are drawn from the green palette with many specimens showing superbly bright neon tentacle tips. Frogspawn corals have less intense colouration and may often appear translucent with white nodules and tips.

Euphyllians are commonly available as fragged specimens and it is these that the conscientious aquarist should seek out to limit collection from the wild.

All Euphyllians will take meaty food items and will welcome chopped seafood and frozen mysis. Whilst the corals’ hide their skeletons well, they do require the Big 3 to be kept at the right levels and will lay down an awful lot of bulk over time as long as you provide it.

Conclusion

So that’s a few corals to get you started, but don’t take my word for it. Read more and explore the subject, whilst this has been a short intro, there’s far more fascinating detail out there. I should add that some aquarists might consider using these corals to ‘test’ themselves and their systems. Even though these animals may be tougher than others and may show more adaptability and hardiness they still deserve to be kept with care and consideration. Take your time and don’t rush, keep on monitoring and checking your water parameters and only add corals when you have achieved stability!

References

Borneman, E. Aquarium Corals, Selection, Husbandry and Natural History. TFH. 2009.

Nybakken, J. Marine Biology, 3rd Ed. Harper Collins. 1993.

Shimek, R. Marine Invertebrates, TFH. 2004.

0 Comments