By James W. Fatherree

The stony corals belonging to the genus Seriatopora are sometimes called bush or needle corals, but they are best known to hobbyists as bird’s nest corals. Specimens of these commonly available corals are often very colorful and attractive, and they are typically fast growers making them good additions to reef aquariums. In this article I’ll give you some background information about them, basic husbandry advice, and highlight some problems they may exhibit in captivity.

Basic Information

The genus Seriatopora lies within the family Pocilloporidae, which also includes many available corals of the genera Pocillopora and Stylophora, as well as corals belonging to a couple of other genera that aren’t seen in the hobby. There are obviously some similarities between these corals, and I’ll point out a couple below. Regardless, there are six species of Seriatopora according to Veron (2000), which are S. hystrix, S. caliendrum, S. guttatus, S. stellata, S. aculeata, and S. dentritica, with S. hystrix being the most commonly seen species in the hobby. All six species can be found in the central area of the tropical West Pacific, and two species (S. hystrix and S. caliendrum) have much greater ranges, also being found as far away as the Red Sea.

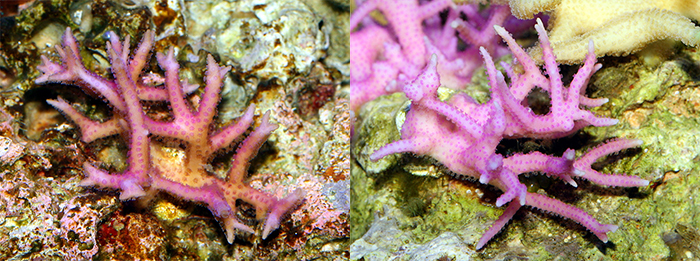

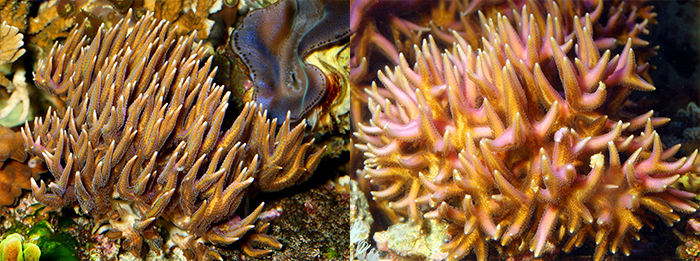

These small specimens of S. hystrix have a very open form, but that typically changes as they increase in size. Also, note the sharp branch tips of this species.

Various specimens come in brown, pink, purple, pale yellow, green, and cream, and often have polyps that are a different color than their background. All of them take on a branching growth form. However, all six species are usually easy to identify as members of the genus, as you just need to take a close look at the arrangement of their polyps that run the length of the branches in neat little rows, which is a feature unique to Seriotopora. Of course, it’s harder to see this on very small specimens and on short branches, but it becomes quite clear as they grow.

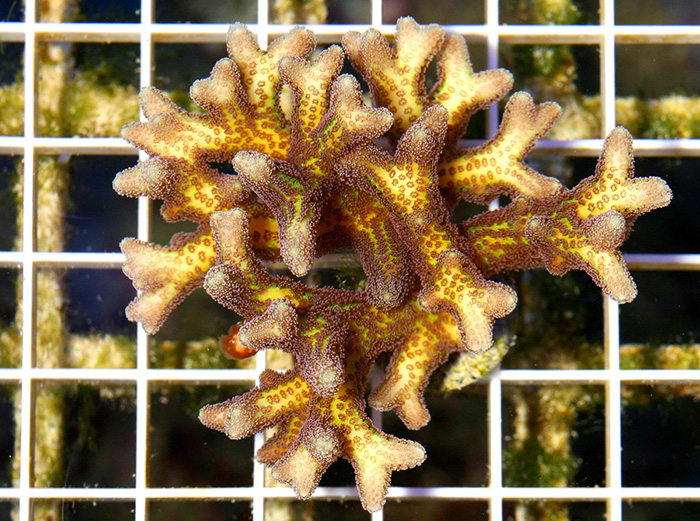

In addition to having polyps in rows, the popular S. hystrix also has distinctive branches that are rather thin and have very sharp tips. However, you may also find specimens of S. caliendrum and S. guttatus from time to time that have thicker branches with rounded, blunt tips. So, you may have to look for those rows of polyps to be sure they’re seriatoporids. As far as I know, I’ve never seen any of the other three species for sale, and neither have the folks at the local shops I frequent.

Here’s an example of S. caliendrum, the second most commonly offered member of the genus. Note the absence of sharp tips on the branches.

When it comes to sexual reproduction, seriatoporids are spawners that release sperm and eggs into surrounding waters, and they can also brood fertilized eggs internally. According to Borneman (2004), they can produce and internally brood asexually-produced larvae, as well. Like most stony corals they can be broken up into pieces as a means of asexual reproduction, too. However, unlike these more common means of reproduction, some seriatoporids and pocilloporids can also make more of themselves via a process called polyp bail-out when stressed, and even occasionally when they’re not.

If polyp bail-out occurs, you’ll see a branch or a patchy area that has lost all of its polyps, which have detached themselves from the rest of the colony and drifted away. Sammarco (1982) noted that under laboratory conditions 5% of polyps released by S. hystrix ended up settling down elsewhere on the substrate and began growing into new colonies, and this has not been uncommon in aquariums housing Pocillopora damicornis. In fact, it’s quite common for new colonies of P. damicornis to spring up all over an aquarium to the point of being a nuisance at times, even under optimal conditions. I, on the other hand, have never personally seen new colonies of S. hystrix arise from nowhere, so either I’ve never had a stressed S. hystrix (unlikely), their polyps die more easily, or I’ve just had bad luck.

Aquarium Care

As far as water quality goes, it should always be within the limits of what is considered appropriate for any reef aquarium. Of course, these are stony corals, meaning you’ll need to pay particular attention to alkalinity and calcium. Alkalinity should be kept between 7 to 12dKH, while calcium should optimally be kept at 380 to 450ppm. Likewise, water flow should be moderate to high for these corals, and turbulent water motion is always better than a non-stop linear flow from one direction.

When it comes to lighting, things get a little trickier, as my own experience has shown that there are no straightforward guidelines for these corals. All of the specimens you may come across can live under anything that would be considered acceptable for a reef aquarium, as lighting systems housing metal halide, L.E.D., or PowerCompact, T-5, and V.H.O. fluorescents, can all suffice.

However, I’ve had specimens of green S. guttatus that would bleach out under T-5 lighting when placed anywhere in the top half of my aquarium. In one case the top half of a larger colony turned completely white when placed high in the aquarium, while the bottom half of the colony kept its green color. So, I moved the whole thing down near the bottom of the same tank and over a few weeks the green came back to the areas it had left, leaving the specimen looking great.

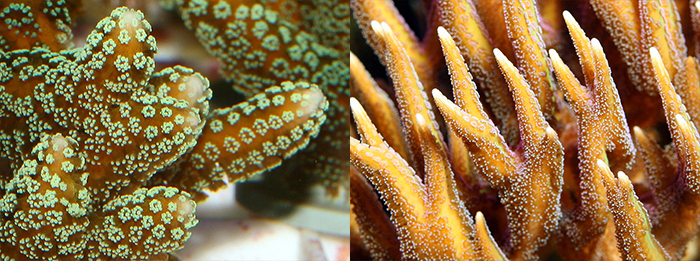

This gorgeous specimen is S. guttatus, typically called the Bird of Paradise coral in the hobby. Note the relatively thick branches with blunt tips.

On the other hand, I had an outstanding specimen of S. guttatus (commonly called a Bird of Paradise) that started to lose much of its bright coloration when placed low in an aquarium and was getting rather dark. So, I moved it up to within a few inches of the surface and it returned to its former glory. I also had a large specimen of pink S. hystrix that I broke into several smaller pieces and spread around, all of which kept their color and grew well. The pieces were placed high, medium, and low, although I ended up losing those up high for reasons covered below.

Like I said, there is no catch-all recommendation here. Even when dealing with different specimens of the same species, lighting requirements can be variable.

There’s one more thing to add here. These corals are indeed found under different lighting in the wild, and it is certainly possible to light-shock any of them that were collected from dimmer waters. If you’re not familiar with the term, it simply refers to rapidly increasing the intensity of light to the extent that it causes problems for a coral. So, if you have really bright lights, you may want to start a specimen on the bottom for at least a few days and then slowly move it up in the aquarium to wherever you want it to stay in a stepwise fashion. This can be a hassle, but the alternative is a bleached, or even dead coral. Of course, you can always start high and then move something down if it starts to bleach out, but you need to watch it very carefully and move it down immediately if you see any loss of coloration.

Potential Problems

Okay, now for a little bad news. I’ve had a couple of notable problems with seriatoporids over the years, the first being that they’re sometimes less tolerant of emersion than other stony corals, and the second being that they don’t like growing down.

Corals of the genus Seriatopora, like this specimen of S. hystrix, can be attractive additions to any reef aquarium.

Anyone that has tried putting new coral specimens in place when an aquarium is full of water knows that cyanoacrylate glue oftentimes doesn’t work particularly well underwater. So, whenever I’ve got a few frags to add to a tank, I typically place some containers (buckets, trashcans, etc.) next to it and drain the water level down far enough so that the spot I’m looking at is exposed. After I take some water out, I then use a paper towel to dab dry the spot where a frag is going, and the glue then works very well. This helps to firmly keep them in place so that they don’t get knocked off the rocks by snails, hermit crabs, and such.

Corals can generally handle a periodic exposure to air like this. However, on more than one occasion, even though every other coral has fared well after exposure, I’ve lost small specimens of Seriatopora. I don’t know why they’d be any different, but like I said, it has happened more than once. This is particularly odd, as I’ve had no problems carrying Seriatopora frags in sealed bags with very little water for extended periods. Yet, when exposed to air at home, they sometimes die.

I’ve got two guesses as to why this has occurred. First, it may be possible that they stay damp enough when in a bag, but get dried out too much when all the water drips off them after draining a tank. Air conditioning does dehumidify air, so I suppose that being exposed to such dry air in combination with drip drying is a bad combination.

The other is that they’re going through some sort of total polyp bail-out, with nothing left behind. It’s possible that the stress of being exposed caused them to do this, and that none of the bailed-out polyps settled into appropriate areas and survived. So, I’d keep any exposure to air at a minimum – no more than a few minutes.

A close look reveals a distinct feature of seriatoporids. Their polyps are in rows on well-developed branches.

In addition, these corals oftentimes have a difficult time growing downwards and covering up any glue or epoxy used to affix them. Generally, when affixed in place, a small-polyped stony coral will rapidly grow over its attachment point and increase the size of its base as the colony grows upwards and outwards. However, for whatever reason, seriatoporids will often grow rapidly upwards and outwards, adding new branches and lengthening old ones, but do a poor job of increasing the size of their base. In fact, I’ve seen many of them grow to several times their original size, while still having the same skinny little base of attachment in a clump of glue or epoxy. As long as you don’t bang one, it’ll probably be fine, but this can be unattractive, nonetheless. So, I try to use the absolute least amount of glue/epoxy possible. Sometimes, all you can do is hope that the spot will eventually be covered by coralline algae.

To make matters worse, on some occasions the area of the base next to the glue/epoxy dies off a bit, leaving part of the skeleton exposed. This happens with other corals at times too, but they usually grow right back over the dead areas. Conversely, seriatoporids that don’t grow downwards won’t cover this dead area. Again, this isn’t very attractive, and it means they’ll have a relatively weak point of attachment as the colony grows, too.

These problems are also common when dealing with pocilloporids and stylophorids, but these are the only I can come up with, so, I still think they’re great corals. You just need to keep them wet and put some thought into how and where you’ll place them. If placed and cared for properly, they can certainly be gorgeous additions to your system.

References

Borneman, E.H. 2004. Seriatopora caliendrum reproduction? (Msg 4). Message posted to: http://archive.reefcentral.com/forums/showthread.php?t=314089

Sammarco, P.W. 1982. Polyp bail-out: An escape response to environmental stress and a new means of reproduction in corals. Marine Ecology Progress Series 10:57-65.

Veron, J.E.N. 2000. Corals of the World, Vol. 2. Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, Australia. 429pp.

0 Comments